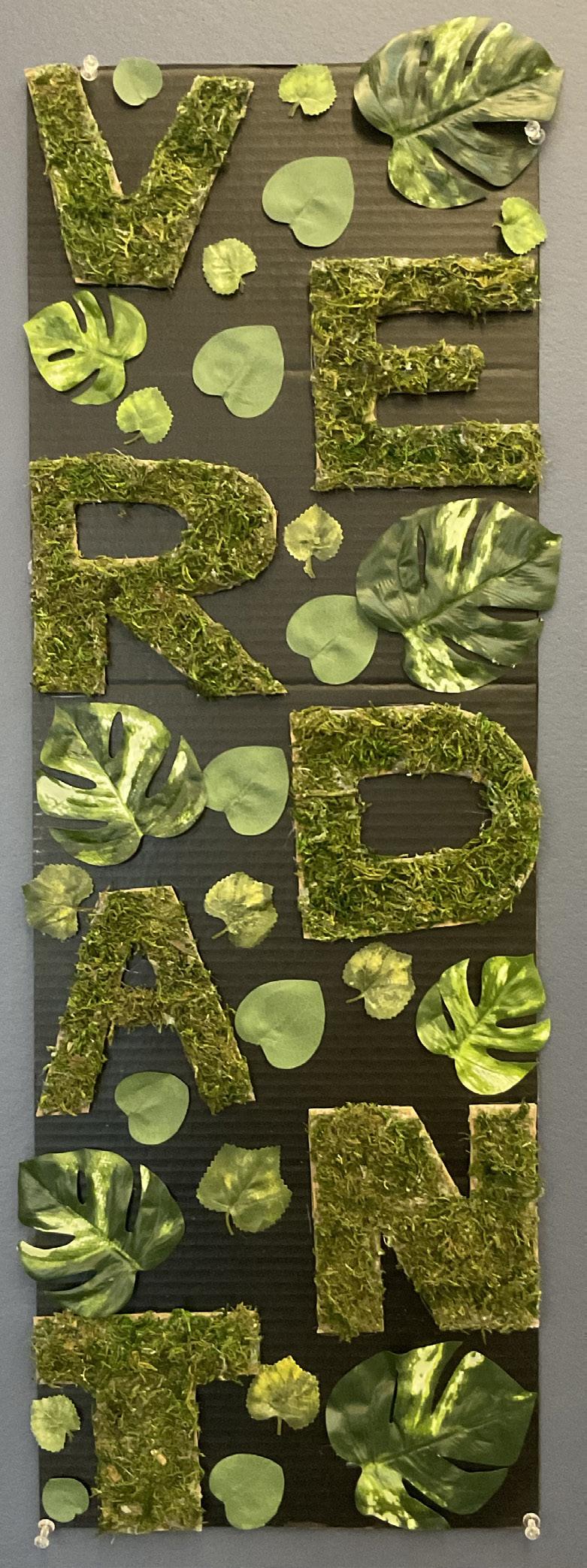

To Be Yourself

Be smart, They are told, Be smart, To rid your woes, Not you, They say, You are already there, You know this, They exclaim, Then, They walk away, I try, To find my crowd, I fail at this, for sure,

For my answer is the same, And here I remain, Near the dirt with the plants I stay.

-Abigail K. Bashur ’30

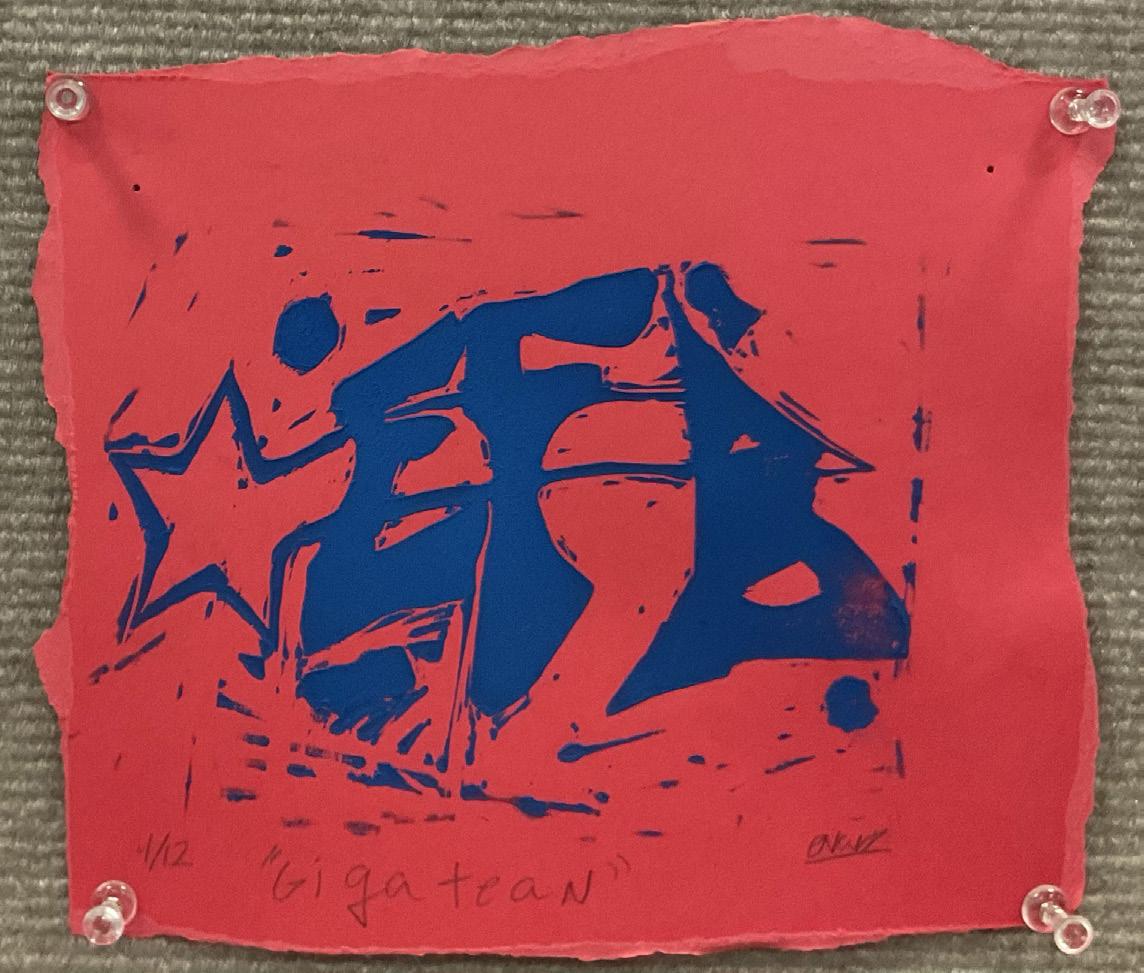

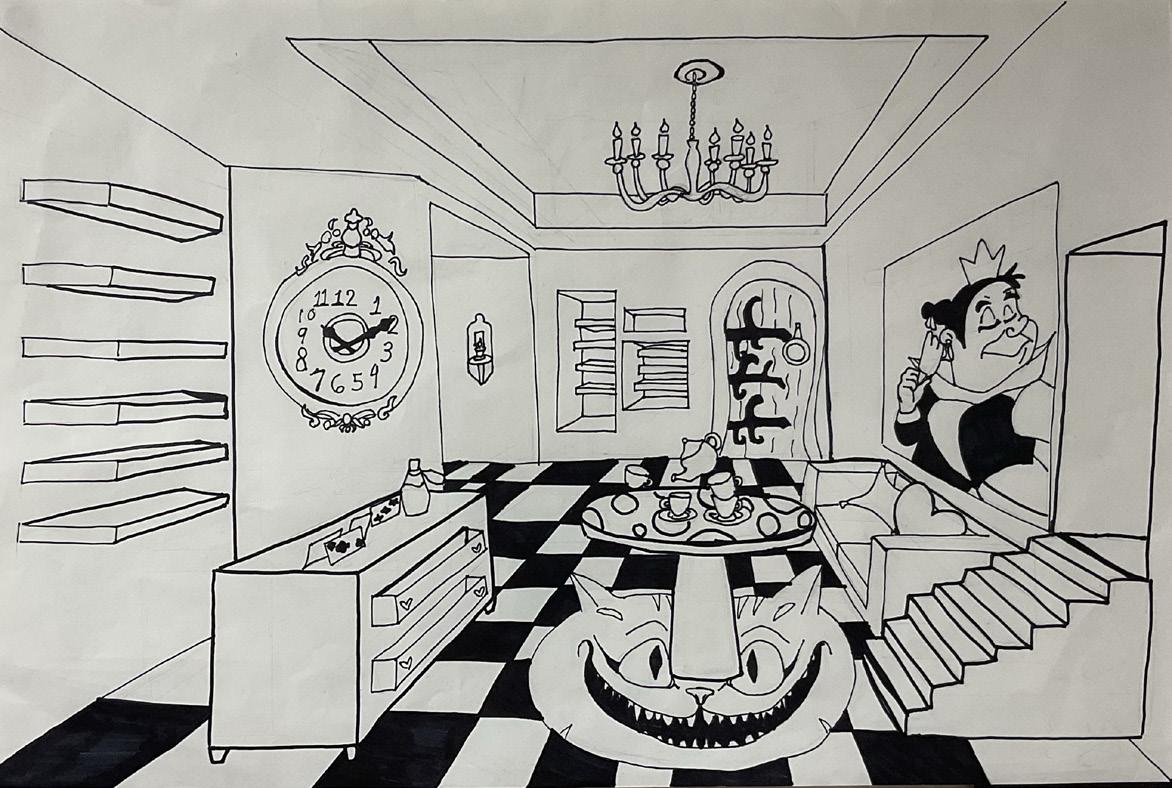

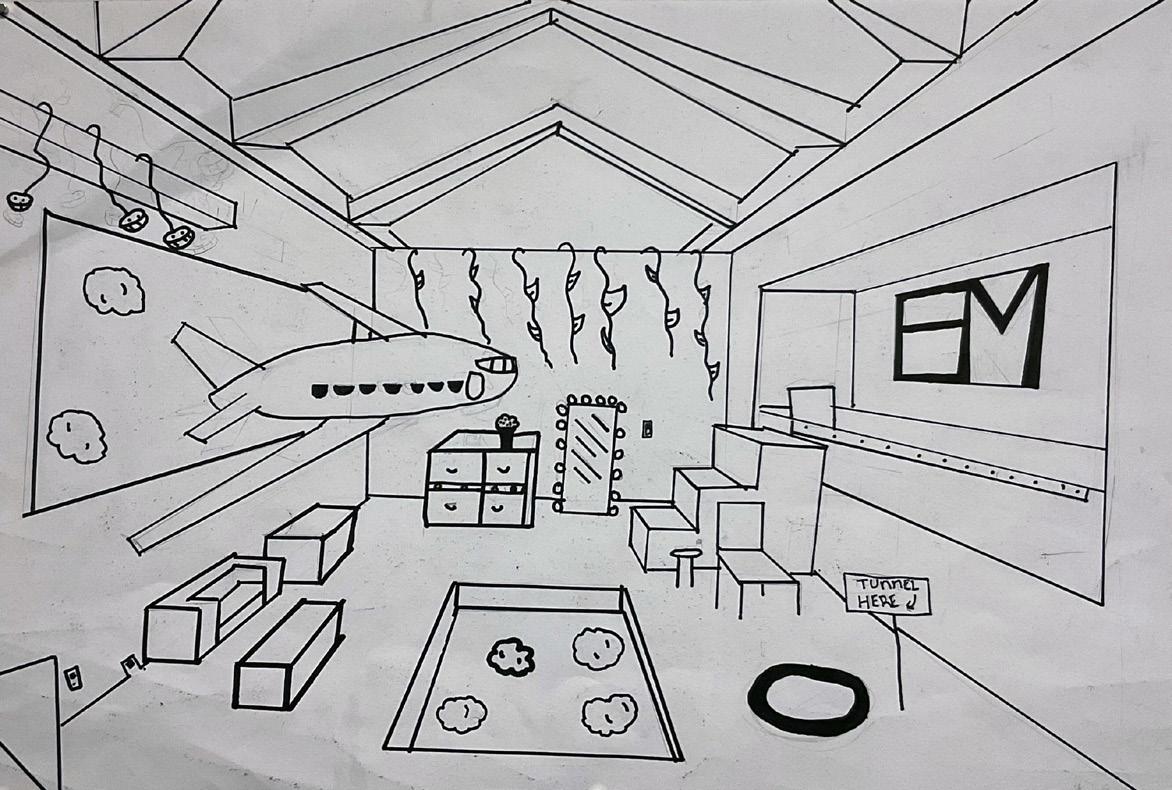

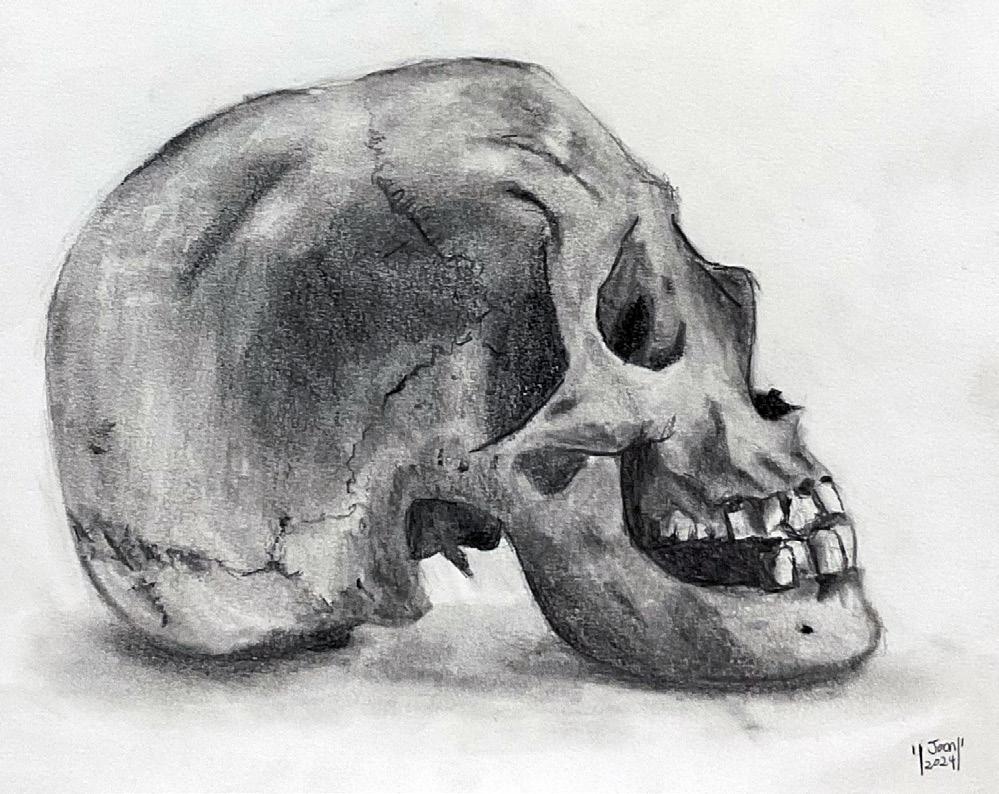

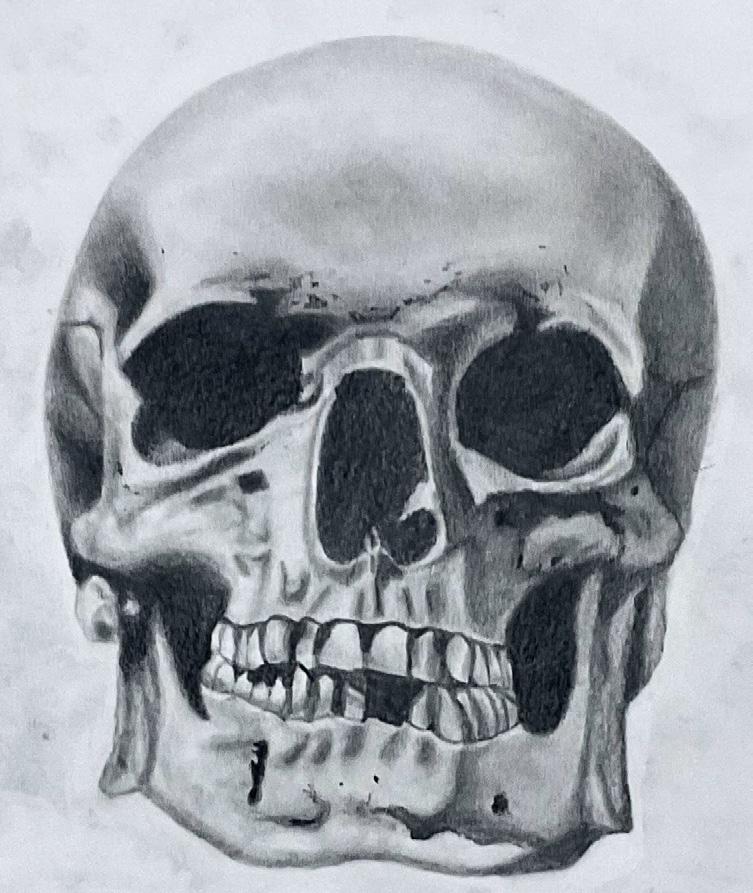

Nolan Treadaway ’28

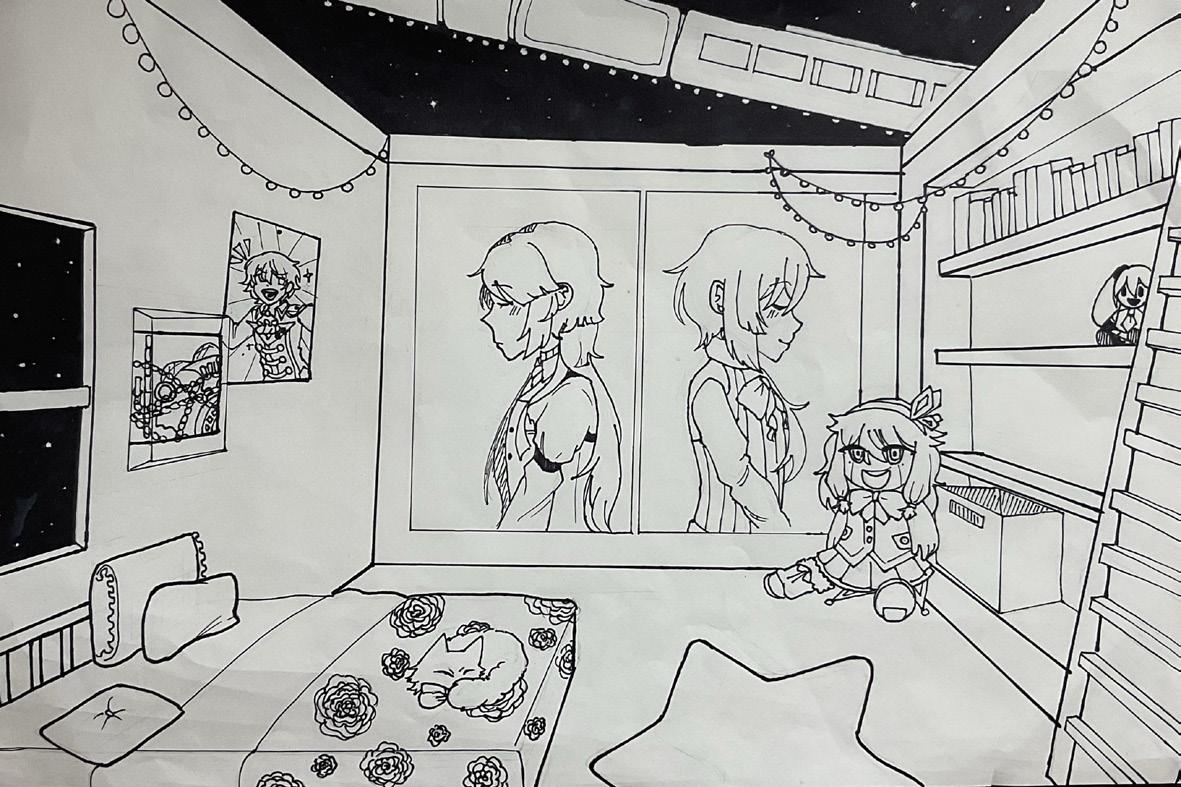

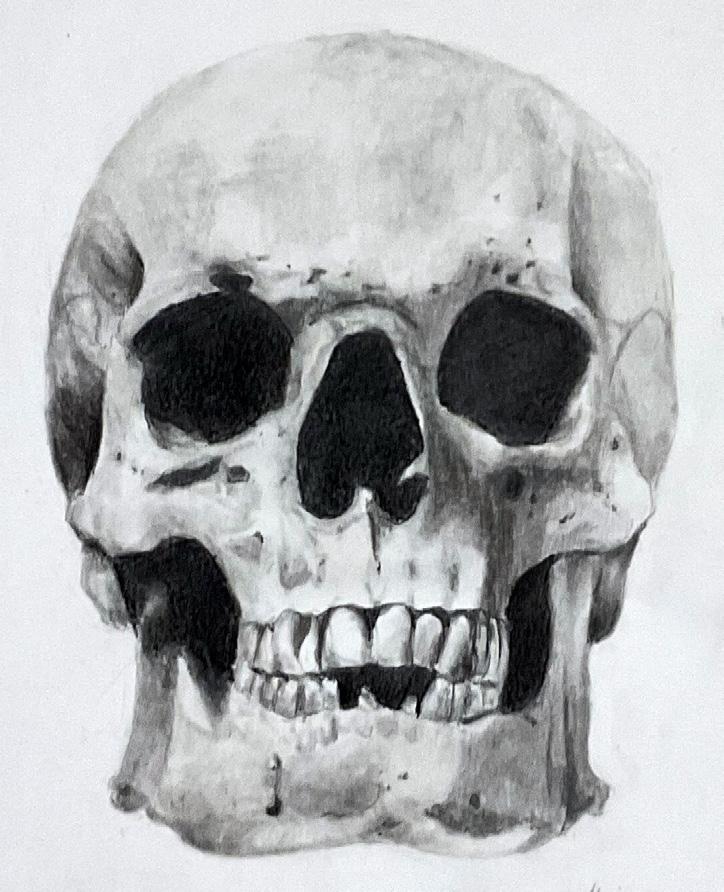

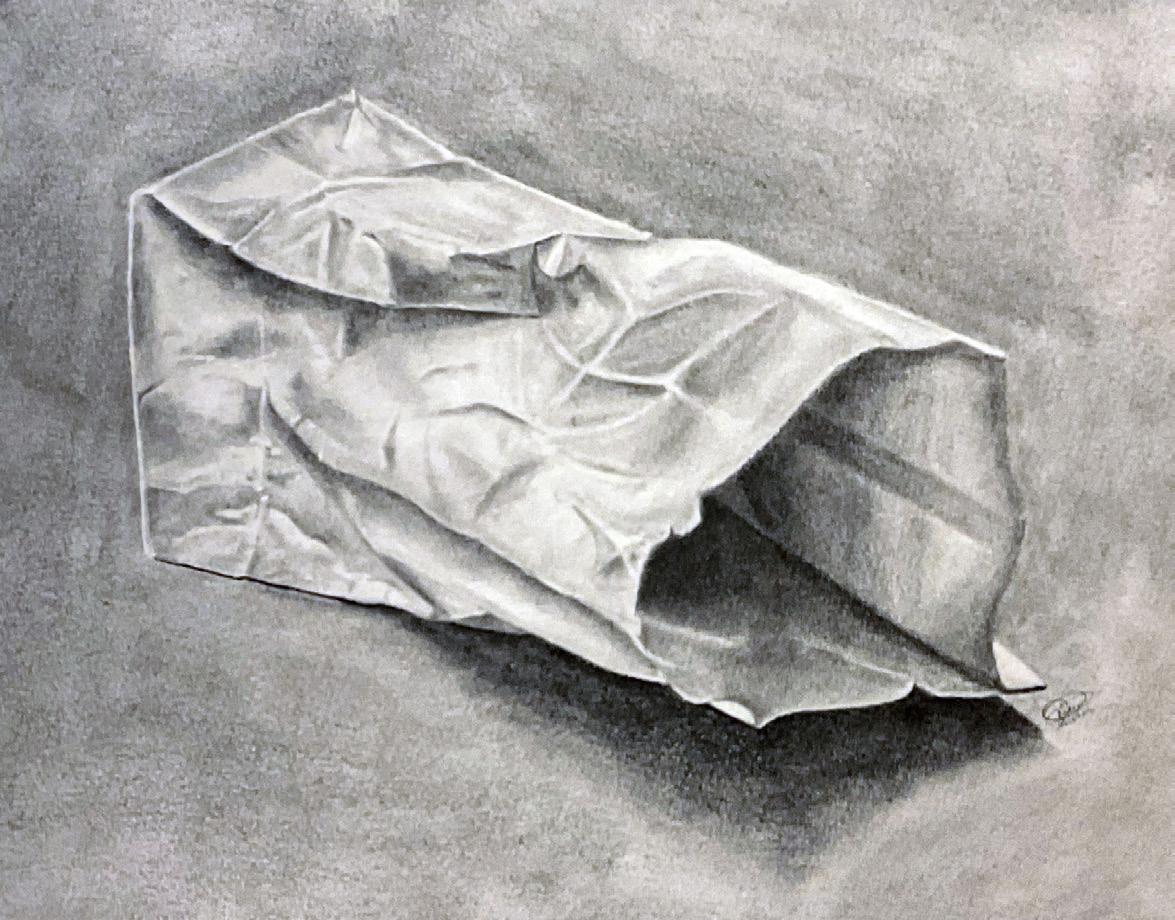

Oliver Hejna ’28

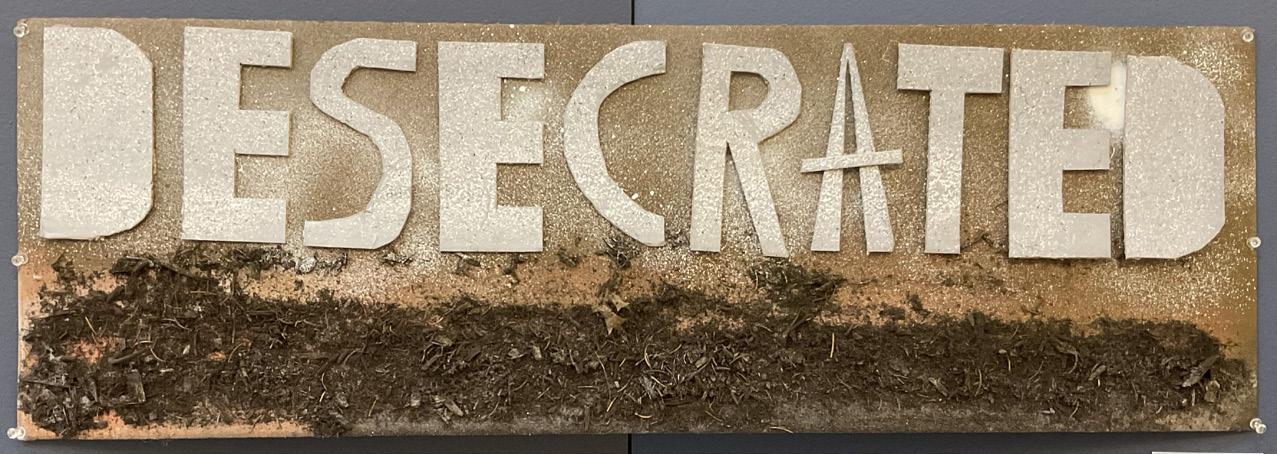

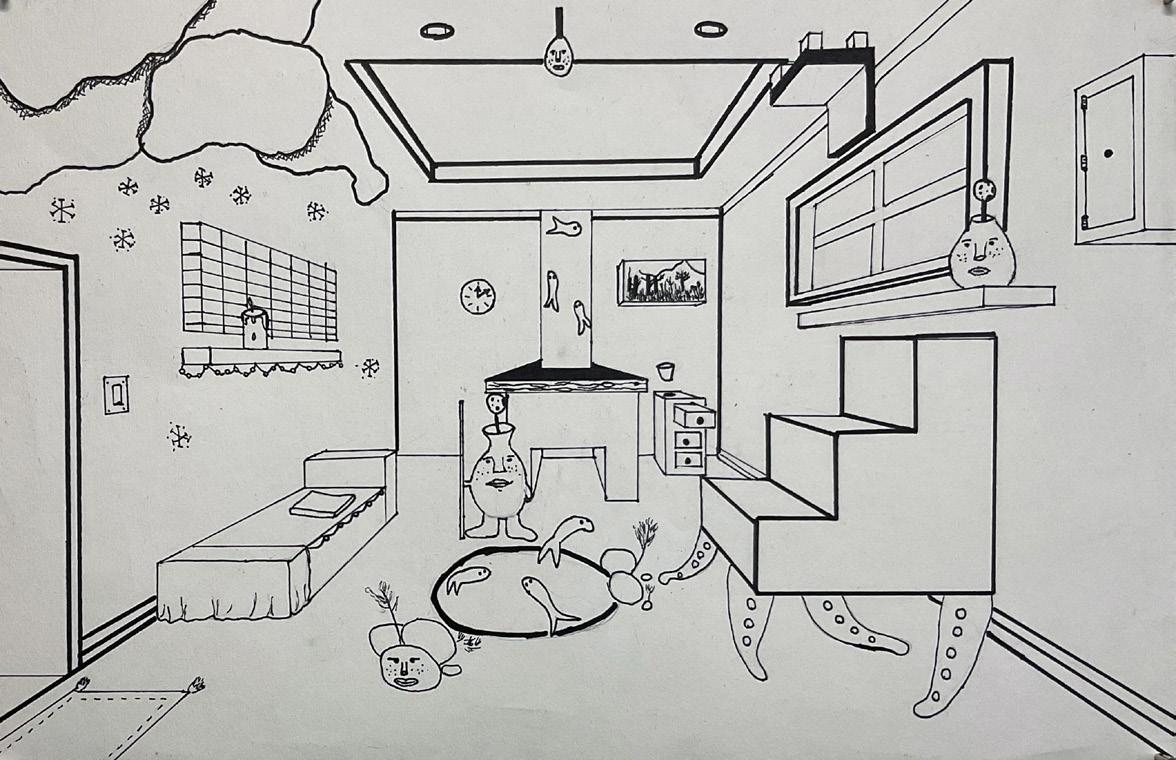

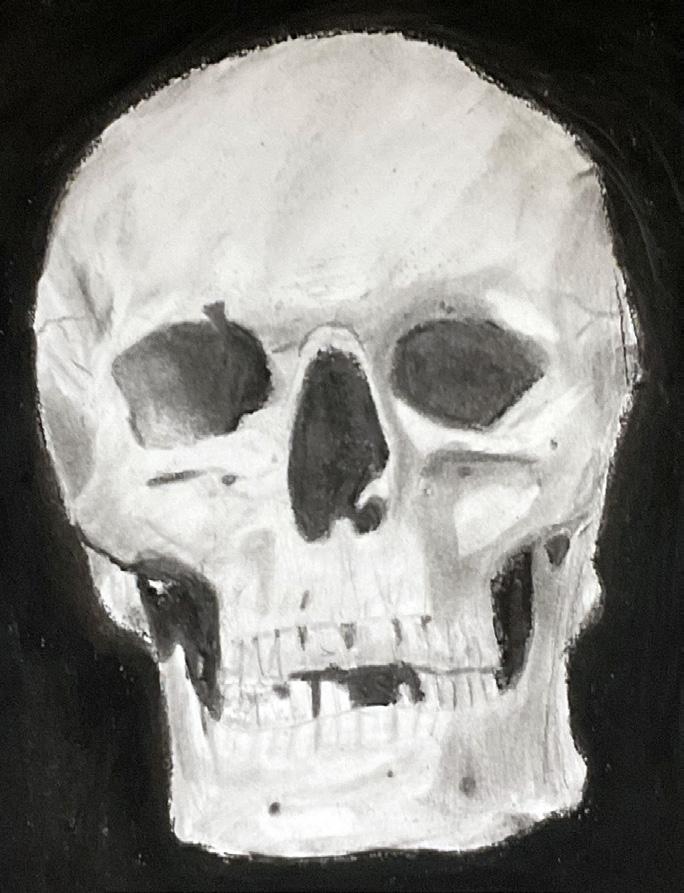

Aubrey Goldstein ’28

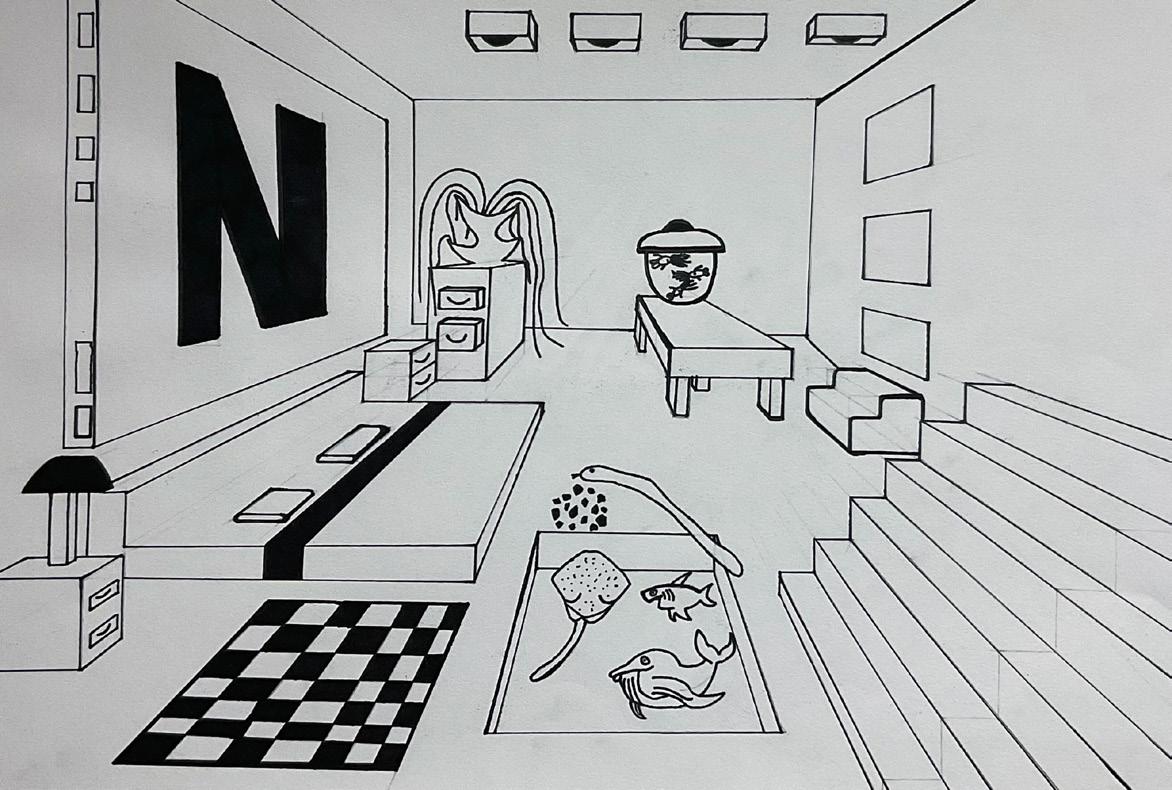

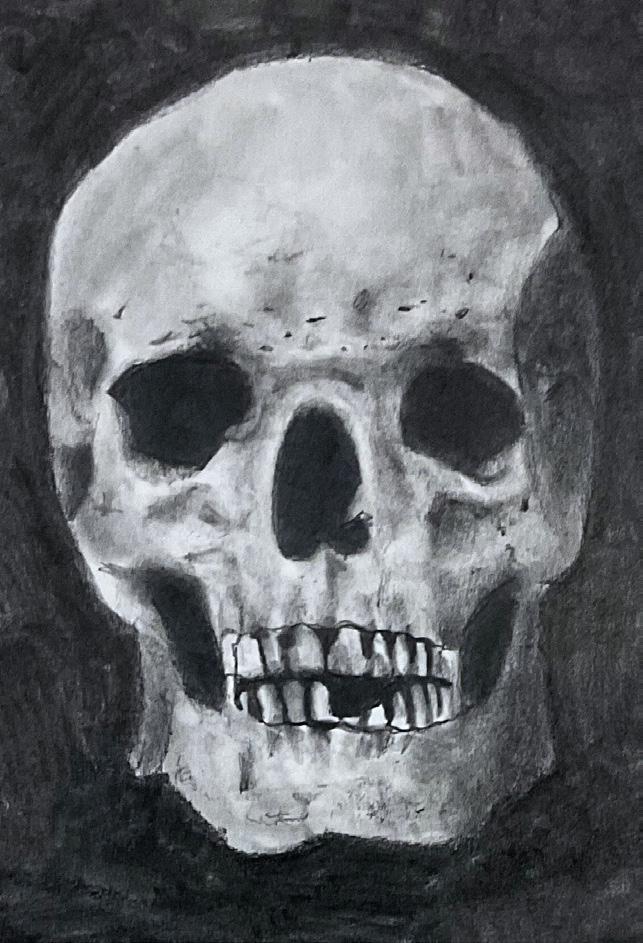

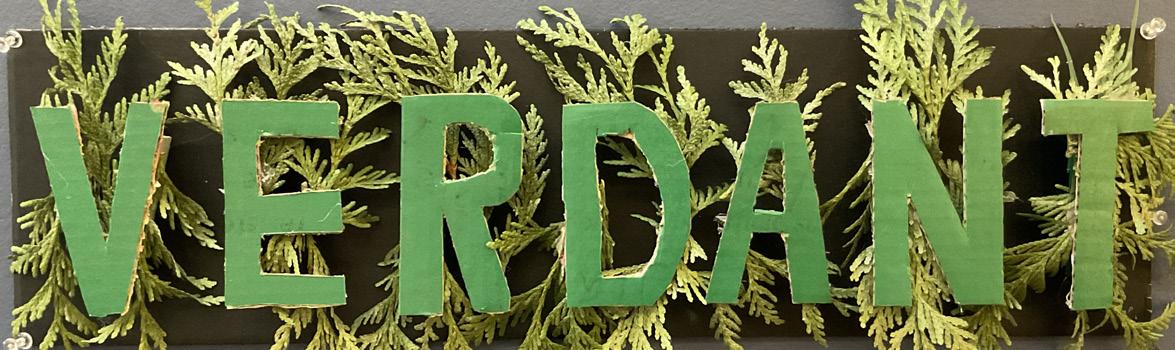

Rowan Kuick ’28

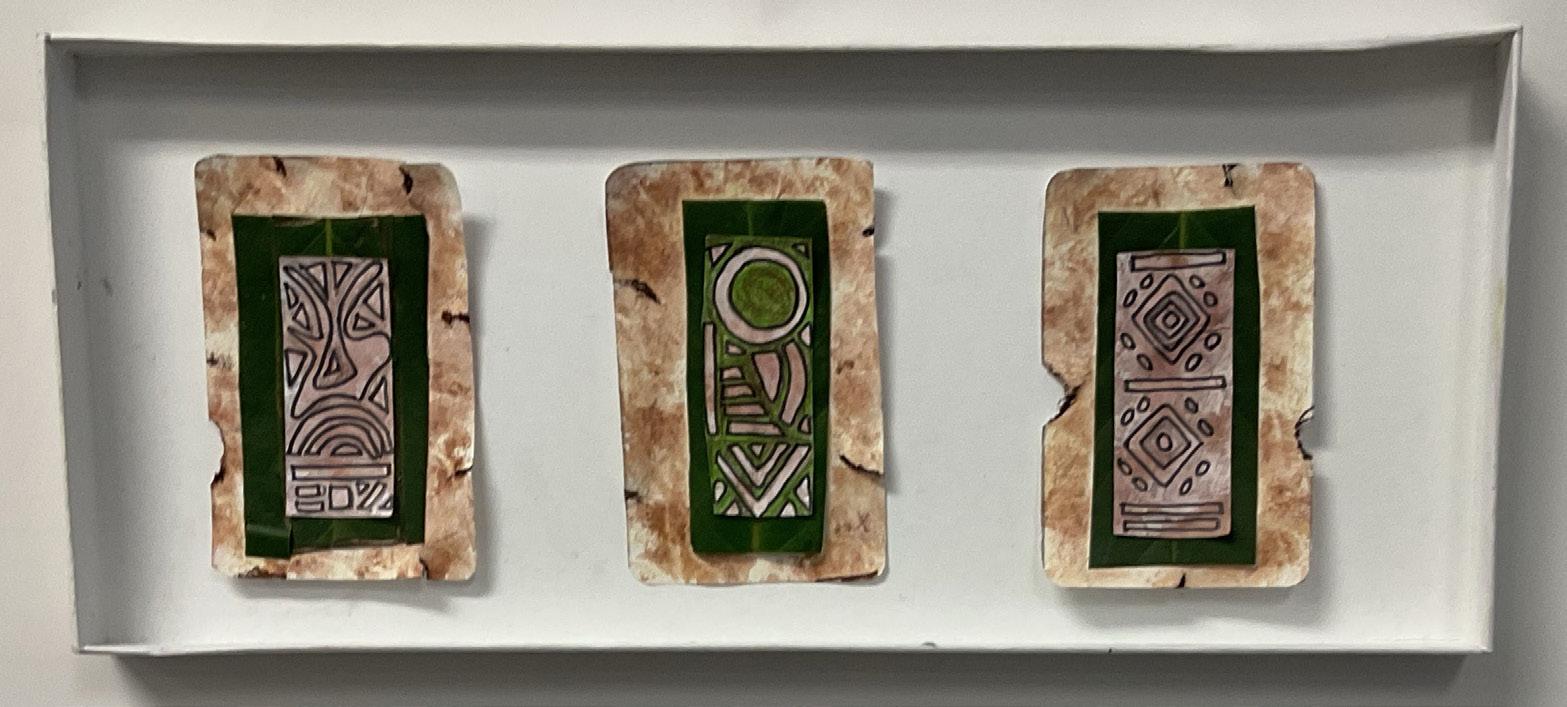

Sophia Ochs ’28

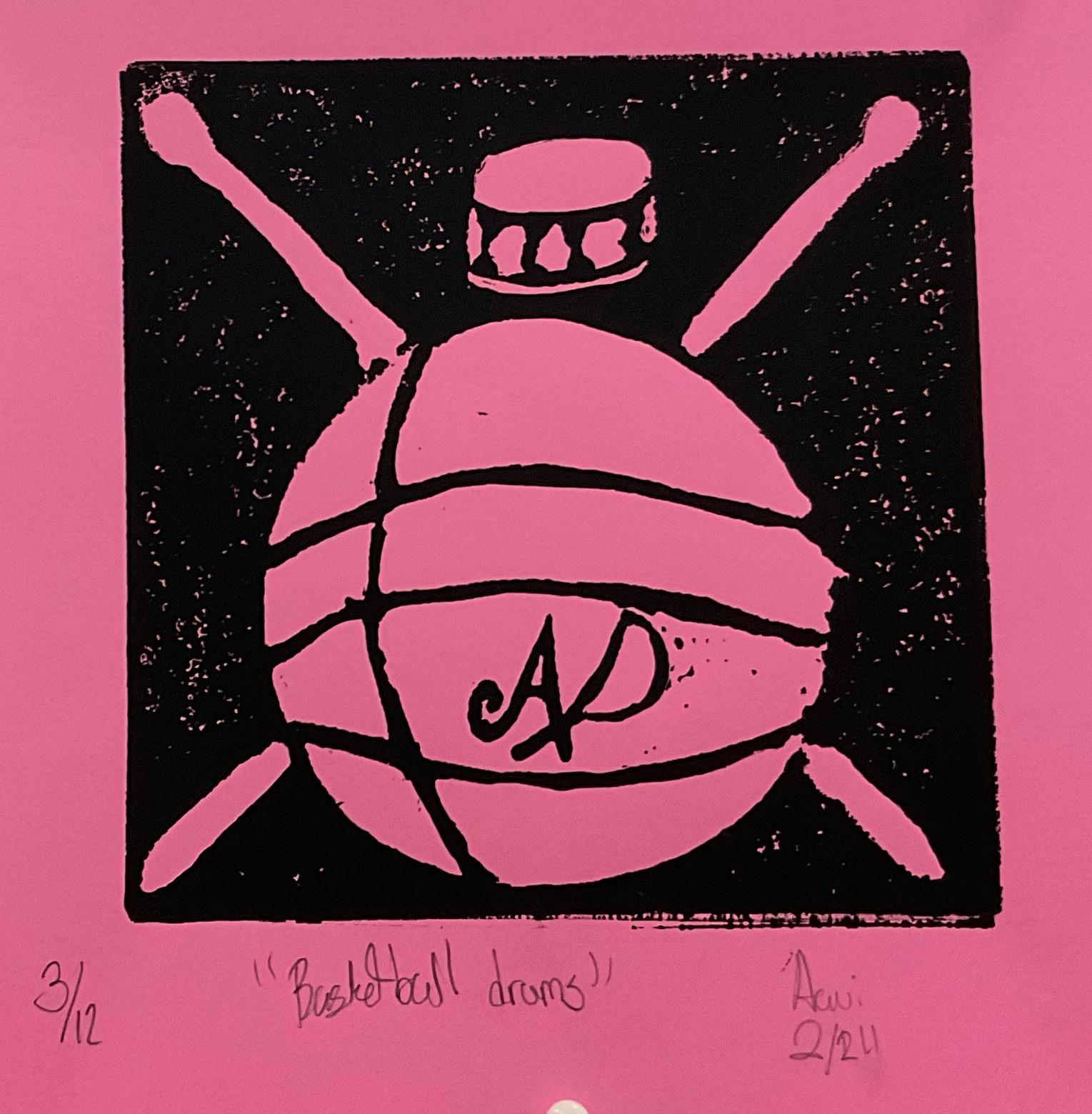

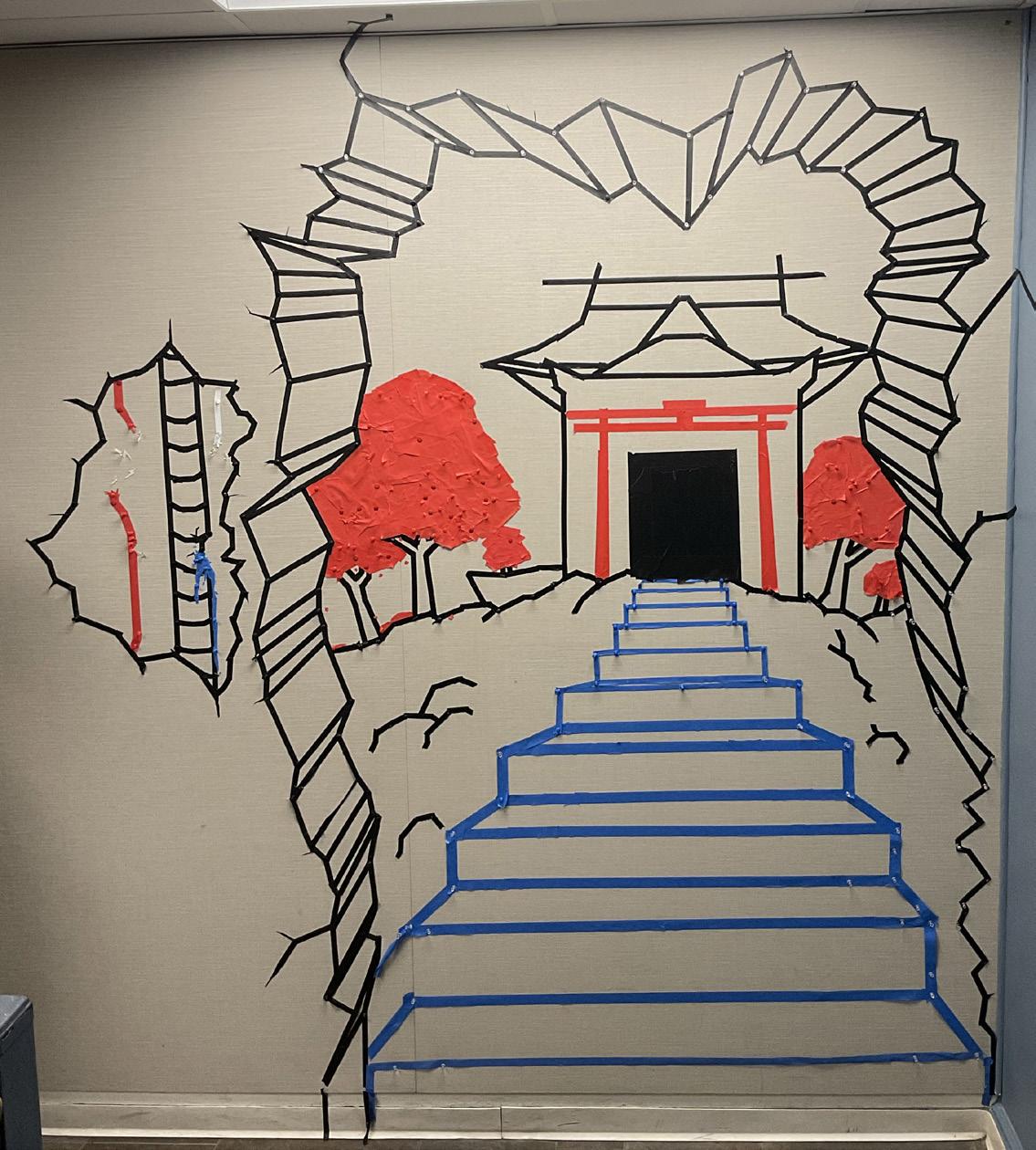

Joonkyu Shim ’32

“Eyes”

“Hairs “ by Sandra Cisneros inspired pieces

By Elle Maghsoudlou ’29

Everybody in our family has different eyes. My mom’s eyes are warm and brown, like chocolate. My eyes are like chestnuts. When they’re raw, they’re bitter. But when they’re soft, they’re sweet. Grandma’s eyes are small and sour, like a bad piece of candy.

My dad’s eyes on the other hand, they’ve got a look, one look of something you almost can’t grasp, you almost can’t see, one look that comes every so often with a sound of spirited laughter, that one look which can make you feel so sorry and leaves you speechless, but if you’re lucky, that same look will make you see stars, bright and shiny ones, dull and gloomy ones, slow and scared ones. Stars of all kinds and looks of sentiment all set in a pair of sights.

“Eyes”

By Naz Johnston ’29

Everybody in our family has different eyes. My dad’s eyes are as blue as ice, speckled with green like shards of prismatine. My sister’s eyes are just like mine, brown, dark, and rich as chocolate. Bolo, my dog, his eyes are incredibly human, as light as wood planks, and deeply saturated.

But my mom’s eyes, my mom’s eyes, like little bronze stars shining from above, like beacons of care that reach far into the ocean and guide me to shore, like a safety net of love and trust because she knows what you need always, and when one of you is sad, the other cares, and when both of you are sad, you hold each other and stay in that infinite embrace for as long as you need, when tears are pouring and you both need someone. Me, my mom, and her beautiful bronze eyes.

“Voices”

By Tej Bakaya ’29

Everyone in my family has a different voice. My brother’s voice is high and silly, like a cartoon character always ready to tell a joke. My mom’s voice is like a chihuahua, sometimes calm, sometimes angry, sometimes happy. My voice is like a perfectly off-tune song, occasionally high, sometimes low, most times in the middle. And my aunt’s voice is multi-accented, like a book with different languages.

My dad’s voice, however, is like a playlist with many different genres. When angry, his voice is fierce and strong, a lion’s roar. When he is calm, he is as cool as a summer breeze, and when he is happy, he has the enthusiasm of a child’s birthday party, joyful and light, he makes you happy, even if you are not, he keeps you calm, even if you are not, he is a beacon in a dark city.

Georgia Aitken ’28, Oliver Hejna ’28, and Eliza Bishop ’28

Aubrey Goldstein ’28, Tamara Regular ’28, Stella Kilcullen ’28, and Madison Lee ’28

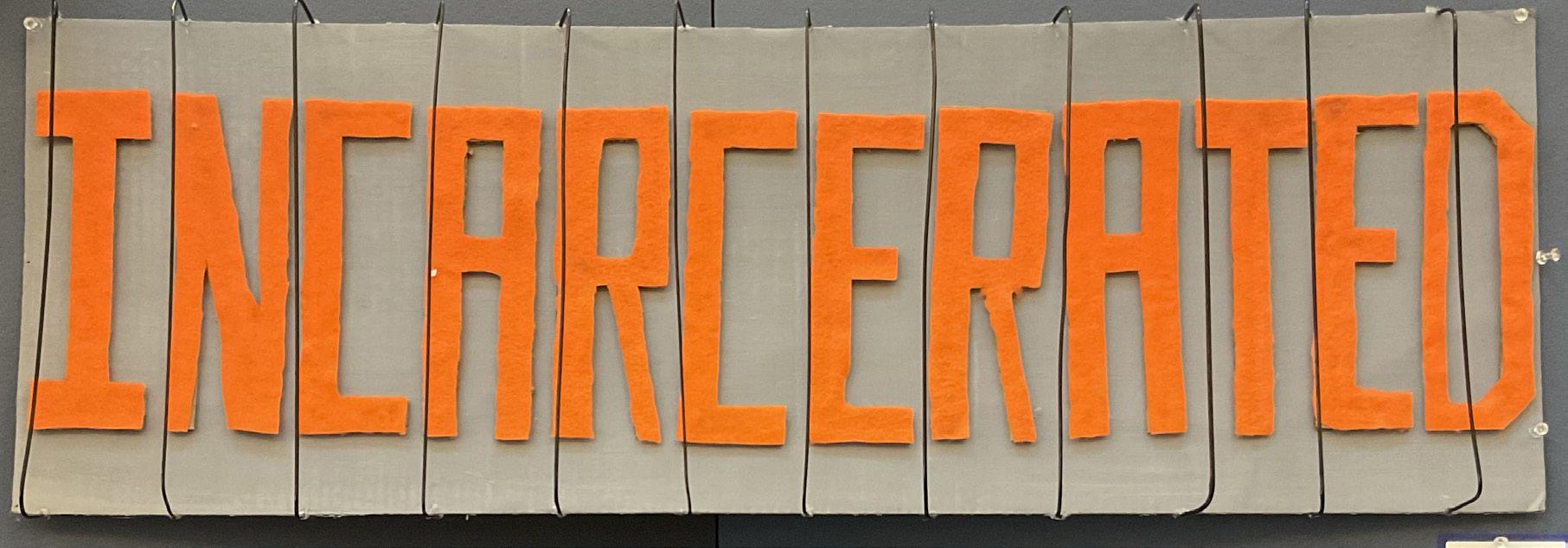

Graham Killebrew

Crime and punishment were much more brutal in old colonial Virginia than today. They were not able to use our methods of punishment, so they used humiliation in place of prisons. In the Virginia colonial cities of Jamestown and Williamsburg, punishment for crimes was humiliating and public because it needed to function as a deterrent and keep law and order due to the lack of resources provided to prisons. They believed that making all of the punishments public would let everybody else see what happens when you break a law and get caught. Most importantly, it embarrassed the criminal and could make them an outcast because everybody would remember what the offender did and the punishment that followed.

Prisons were not viable in the old colonial cities of Virginia because money for their resources came out of citizens’ pockets, and they valued their own lives more than criminals. The prisons were terrible because prisoners needed warmth, food, water, and shelter, but the money for those resources had to come from innocent people who valued their own needs more than a stranger that had committed a crime.1 People didn’t want to use the money they would have spent on themselves just so a convict could be more comfortable; however, this could result in death for some or most inmates. Since the people that paid for the prisoners got to choose how much food, water, and warmth each of them got, most inmates had to bribe people on the outside to keep them alive with enough resources, and the ones that didn’t have the money would die of neglect.2 Since no one on the outside was paying for the inmates’ needs, the convicts bribed people to pay for their necessities, all so they could pay them back when they got out. When prisons became overcrowded, the money for resources increased, and taxpayers did not want to make a convicted life more important than their own.3 This means that jail time for criminals wasn’t a viable option because they didn’t have the resources to provide free food and shelter for everyone who committed a crime. There had to be money coming from somewhere to pay for the resources prisoners needed, and that place was taxpayers’ pockets. When they found out what they were paying for, they immediately refused to pay anymore because they valued their lives and their families’ lives more than criminals. This led to prisons not being a viable option and made the government resort to much harsher, more brutal, and more permanent tactics.

The government found using public shame for the crimes committed was the best way to humiliate and punish the criminal. They invented the scarlet letter, which would hold someone’s head in an uncomfortable position to publicly shame them. Everybody would gather around to shame the convict, holding them for hours, even days, without letting them move until they were free to go.4 This was an easy way to publicly humiliate the criminal because, for the rest of their lives, everyone in the community would see them as a convict. The community would often call people who committed crimes sinners. One of the common shaming punishments was forcing them to sit in the stocks in public view. This was one of the mildest punishments for warnings and fines, but bystanders and citizens were also allowed

1 Jim Cox, “Colonial Crimes and Punishments” [Colonial Crimes and Punishments], Colonial Crimes and Punishments, accessed November 2, 2023, https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/Foundation/journal/spring03/branks.cfm.

2 James Cox, “Bilboes, Brands, and Branks Colonial Crimes and Punishments” [Bilboes, Brands, and Branks Colonial Crimes and Punishments], Colonial Williamsburg, accessed November 15, 2023, https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/ Foundation/journal/spring03/branks.cfm#:~:text=Colonial%20 practice%20took%20the%20matter,way%20back%20to%20 the%20flock

3 Cox, “Colonial Crimes,” Colonial Crimes and Punishments.

4 Cox, “Bilboes, Brands,” Colonial Williamsburg.

to throw garbage at them.5 This was extremely effective because they didn’t have to hurt you or do anything permanent, but it encouraged regular citizens to treat you like you weren’t even human. Humiliation was used as the most useful punishment to compel people to never commit a crime again.6 These methods would scar lawbreakers for the rest of their lives and make them an outcast to everyone who remembered the time that they were humiliated.

Another method of shaming involved branding letters directly on the skin to leave scars for everyone to see, labeling them as convicts. Burglars were punished by branding a capital B on the right hand for the first burglary and again on the left for the second burglary. If either were committed on the Lord’s Day (Sunday), the brand would go on his forehead.7 This was an easy method because it would permanently scar the burglar. For the rest of their lives, they would have to live either trying to hide it so people would accept them and interact with them, or they would have to just become an outcast in society since no one wanted to be around a burglar. They would brand an M on you for manslaughter, a T if you were a thief, and an F for forgery.8 This also made others distrustful from the moment they saw the branded letter. Cutting people’s ears off was another form of disfigurement to permanently remind them and others of their behavior. They put criminals in headlocks and nailed their ears to the board behind them. The only way to free their ears from the nails when they were allowed to leave was to either rip them off or get someone to cut off their ears. Crowds would gather to watch things like this.9 If bystanders couldn’t participate in the humiliation of the criminal, the second best thing they could do is gather around and watch this brutal torture. The citizens thought of this as a source of entertainment even though it was so violent. They were taught to help shame the person even more, as if getting their ears nailed to a board wasn’t enough. The fear of these permanent torture methods scared many into abiding by the rules and laws.

For a long time in old colonial Virginia, the death penalty was used as the most extreme of the four main punishments. Still, the death penalty wasn’t of much help for long because of a rule that let criminals avoid it by just reciting a line from the Bible. Public hangings were completely normal and a punishment that they turned to often because it would be humiliating for the family of the accused, and the citizens would never have to worry about that person ever committing another crime.10 If a public hanging could accomplish humiliating a person’s family and other citizens could also see the lifeless body dangling from the rope every day until it’s taken down, it could also deter others from committing a crime because they would be aware of the consequences. It wasn’t as useful as time went on because when word spread of a way to get out of the death penalty by reciting a passage from the Bible, everyone started using it. Since the most common death penalty was being hung, they called this strategy “the neck verse.”11 There was a rule put in place early on that if a person read a passage from the Bible about God wanting them to have a second chance, the judge would have to let them live. This wasn’t a bad thing for a while since not many people could read. However, soon more people learned how to

5 Cox, “Bilboes, Brands,” Colonial Williamsburg.

6 Cox, “Colonial Crimes,” Colonial Crimes and Punishments.

7 Natasha Frost, “Was the Colonies’ First Death Penalty Handed to a Mutineer or Spy?” [Was the Colonies’ First Death Penalty Handed to a Mutineer or Spy?], HISTORY, accessed August 24, 2018, https://www.history.com/news/death-penalty-jamestown-virginia-colony.

8 Natasha Frost, “Was the Colonies’ First Death Penalty Handed to a Mutineer or Spy?” [Was the Colonies’ First Death Penalty Handed to a Mutineer or Spy?], HISTORY, accessed August 24, 2018, https://www.history.com/news/death-penalty-jamestown-virginia-colony.

9 Cox, “Bilboes, Brands,” Colonial Williamsburg.

10 Frost, “Was the Colonies,’” HISTORY.

11 Cox, “Bilboes, Brands,” Colonial Williamsburg.

read, and even the ones that couldn’t were able to memorize the words of “the neck verse.” Eventually, they stopped using the death penalty for robbery, burglary, and sodomy. The only crime that could still be punished by the death penalty was murder.12 When the death penalty could not be used as much as it was previously, they had to rely even more on permanent scars like branding and public shame.

The four main punishments used to be much harsher and more brutal than any other punishments that we have today. They could use severe torture for small crimes if they thought it would be appropriate. They also tailored their punishments to fit the crime that was committed no matter how painful or cruel they were. The four main types of punishments used were public shame, fines, physical chastisement, and death.13 Any of these four punishments could be used on you if they thought it was the best option for the crime you committed. If it was an uncommon crime, they tried to make the punishment similar to the crime committed. The punishments were brutal in terms of humiliation and modern ways of torture.14 Even though it wasn’t one of the main punishments, it could fall under the category of physical chastisement. The death penalties used were burnings, hangings, and crushing people to death.15 The reason these methods were used was because they wanted everything to be public and painful for the convict. They would make the punishment fit the crime, but to an extreme level, so nobody missed the point and everyone understood what rule or law was broken.16 If the punishments fit the crimes that were committed, the person being punished would have a better understanding of what they did wrong and hopefully not make the same mistake in the future. Punishments were much harsher, more brutal, and humiliating back in old colonial Virginia. The reason the colonists made punishments this way was because it was vital that the lawbreaker would learn from what they did wrong and never do it again. There was also an easy way to punish them for the rest of their lives with something permanent like branding, or something so humiliating that no one would ever forget it. This would also act as a deterrent to let everybody watching know what would happen if they got caught in the act of a crime. The magistrates were happy when they heard public confessions of guilt

12 Lynch, “Colonial Williamsburg,” Cruel and Unusual Prisons and Prison Reform.

13 Jack Lynch, “Colonial Williamsburg” [Colonial Williamsburg], Cruel and Unusual Prisons and Prison Reform, last modified June 2011, accessed November 12, 2023, https://research. colonialwilliamsburg.org/Foundation/journal/Summer11/prison.cfm.

14 Peter Inker, ed., “Crime and Punishment…and Human Rights” [Crime and Punishment…and Human Rights], Colonial Williamsburg, last modified December 9, 2021, accessed November 2, 2023, https://www.colonialwilliamsburg.org/learn/ living-history/crime-and-punishment-and-human-rights/.

15 Cox, “Colonial Crimes,” Colonial Crimes and Punishments.

16 Cox, “Colonial Crimes,” Colonial Crimes and Punishments.

because they knew the punishment was working.17 They were satisfied when the criminal was suffering and confessing to try to get out of the punishment, and this helped them know how effective different penalties were.

Bibliography

Carter, Robert. Letterbooks. Accessed January 7, 2024. https://digitalcollections.colonialwilliamsburg.org/ CS.aspx?VP3=SearchResult&VBID=2RERI3ZAIM4F &PN=19&IID=2RERYDM9Z2.

Cox, James. “Bilboes, Brands, and Branks Colonial Crimes and Punishments” [Bilboes, Brands, and Branks Colonial Crimes and Punishments]. Colonial Williamsburg. Accessed November 15, 2023. https://research. colonialwilliamsburg.org/Foundation/journal/spring03/ branks.cfm#:~:text=Colonial%20practice%20took%20 the%20matter,way%20back%20to%20the%20flock.

Cox, Jim. “Colonial Crimes and Punishments” [Colonial Crimes and Punishments]. Colonial Crimes and Punishments. Accessed November 2, 2023. https://research.colonialwilliamsburg. org/Foundation/journal/spring03/branks.cfm.

Crime and Punishment. Vol. 1 of Crime and Punishment https://www.google.com/books/edition/Crime_And_ Punishment/4Vd0DwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq= crime+and+punishment&printsec=frontcover.

Frost, Natasha. “Was the Colonies’ First Death Penalty Handed to a Mutineer or Spy?” [Was the Colonies’ First Death Penalty Handed to a Mutineer or Spy?] HISTORY. Accessed August 24, 2018. https://www.history.com/news/death-penaltyjamestown-virginia-colony.

Inker, Peter, ed. “Crime and Punishment…and Human Rights” [Crime and Punishment…and Human Rights]. Colonial Williamsburg. Last modified December 9, 2021. Accessed November 2, 2023. https://www.colonialwilliamsburg.org/ learn/living-history/crime-and-punishment-and-humanrights/.

Lynch, Jack. “Colonial Williamsburg” [Colonial Williamsburg]. Cruel and Unusual Prisons and Prison Reform. Last modified June 2011. Accessed November 12, 2023.

Turnpike, Sherman, ed. Colonial America. Vol. 7 of Colonial America

17 Cox, “Bilboes, Brands,” Colonial Williamsburg.

The Unknown Influence the Navigation Acts Had on the Colonists and the American Revolution

Agatha Greenberg ’28

The sound of fireworks and the smell of the burgers being grilled are things countless Americans look forward to every summer. Everyone knows the Fourth of July celebrates the United States’ independence from Britain in 1776. However, what many aren’t aware of is the reason the colonials wanted their own government. When the House of Burgesses met up in Williamsburg, they complained about the taxes that England was unfairly forcing upon them. As a result, they wanted to suppress this inequality and fight back against Parliament. An example of this is the renowned story of the Boston Tea Party, a protest against the newly instituted Tea Act of 1773. But that wasn’t the first time the colonists disapproved of these statutes. The United Kingdom has been demanding money by passing unfair laws since Jamestown was founded. Not only is this legislation arbitrary, but some of it could even be considered illegal. England didn’t see a problem with this because they thought they could do whatever they wanted with their power. They were using Mercantilism, a very popular British concept in the Early Modern period. And once people get a taste of power, they usually want more. That’s why the United Kingdom created the Navigation Acts: to increase their dominance while preventing the colonies from gaining any strength of their own. In due course, the colonists became resentful of the laws passed and the taxes they had to pay due to them.1 Mercantilism and the Navigation Acts greatly impacted American history; not only did it shape the economy but it also led to the revolution.

Mercantilism played an incredibly large role in Colonial America and was the backbone of the Navigation Acts. It is an extremely important British concept concerning Economics and is a “form of economic nationalism” because it was developed to affect the public economy when feudalism was replaced by nationalism. Mercantilism was incredibly important because it made way for many advances in the economy. It allowed for the development of manufacturing, agriculture, a powerful merchant marine, and a profitable harmony of trade by installing colonies that responded to a specific country and government intervention in matters of trade in order to accumulate wealth through gold, silver, and various resources by trading with many powerful nations. Additionally, Mercantilism was a practice the British government set in place to be able to intervene in commerce and establish colonies so that the country would increase its profits. It was a concept that stated that colonies would only be allowed to trade with their mother country. In England’s situation, this meant that the Thirteen Colonies would send over raw agricultural materials, and in response, England would send back finished luxury goods. The entire idea of Mercantilism is that a country makes more money by exporting more than they import. If England were to buy cheap resources from their colonies and send back expensive commodities, they would make a large profit. An added consequence is that it also helped many other aspects of the economy. This is why England used it.2 In reality, Mercantilism was responsible for the development of the American economy.3 Without Mercantilism, the colonies wouldn’t be able to get their feet off the ground. The support from Britain was the only way the colonies were able to survive because they helped

1 “1651 — Navigation Acts,” Stamp Act History, accessed December 6, 2023, http://www.stamp-act-history.com/timeline/27/

2 Mark Mayo Boatner, Encyclopedia of the American Revolution (New York: Stackpole Books, 1994), 700.

3 “Mercantilism,” American History, last modified 2023, https://americanhistory.abc-clio.com/Topics/Display/1183173?cid=41 &sid=1183173.

with shipping, expansion, and investment opportunities.4 When the colonists first landed, they had nothing. So they needed help from a developed European country like Britain. It was used because it was constantly guaranteed that money and goods would be traded, which was a stable and reliable way of increasing both economies.5 However, the colonies weren’t allowed to manufacture things due to English law and were forced to import every luxury item from Britain. This allowed Britain to obtain a profit because the colonies were paying them more for luxury goods than they were paying the colonies for agricultural goods. If the colonies were able to make their own items, Britain would lose out on this money. And after the English recession of 1620, the UK was keen on being profitable.6 Due to Mercantilism, colonists could not accumulate wealth or gain any “economic independence,” but the English prospered substantially.7

England thought it was okay to tax the colonies because they founded the “New Land” with the sole objective of amassing wealth. They believed that the Thirteen Colonies would supply the United Kingdom with many resources that would increase their profits during trade.8 This supported their Mercantilist ideals and would help Britain get back on their feet after their recent economic decline. When people came looking for the “New World,” they came looking for money and gold. North America, from the beginning, was only thought of as a place to find economic gain. That is why England felt no guilt when taxing the colonists. They figured that they should tax the place that is supposed to be providing them with lots of money.9 The thought was that it was a mutual understanding that Virginia was founded solely for wealth accumulation and written in their laws were mercantilist ideals.10 In fact, taxation was a part of the colonies before anyone even stepped foot on the foreign continent. Because noblemen invested in private investment companies, which were established by the royal charter, the colonies were able to produce many goods to ship back to England.11 Charter companies consisted of a group of wealthy landowners who financed the trips to the “New World” in hopes of receiving some profit in return. As well as money, they received benefits from the King himself. This is a perfect example of Mercantilism in a smaller frame. Similar to countries and their colonies, the nobles are giving the people boarding the ship a chance to start anew, but once they arrive the wealthy want something in return.12 This made sense, of course, in the 17th century. In the age of Mercantilism, Britain saw Colonial America as land that could be easily acquired and would provide them with many raw materials.13 England figured they could tax the colonies however much they wanted because the “New Land” was founded with promises of resources and profits in return for protection.

The Navigation Acts were legislation that supported mercantile values and were set in place to increase the dominance of Britain while restricting the colonies’ strength. Due to the recession of 1620 in England, British civilians decided to focus more on their policies of trade. They needed a strategy to increase their profits.14 It was quickly decided; Mercantilism was the answer. In order to

4 “Mercantilism.”

5 “Mercantilism.

6 “Mercantilism.”

7 “Mercantilism.”

8 Boatner, Encyclopedia of the American, 700.

9 U.S. Department of State, “The U.S. Economy: A Brief History (Outline of the U.S. Economy),” USEmbassy.gov, accessed November 1, 2023, https://usa.usembassy.de/etexts/oecon/chap3.htm.

10 U.S. Department of State, “The U.S.,” USEmbassy.gov. 11 “Mercantilism.”

12 U.S. Department of State, “The U.S.,” USEmbassy.gov. 13 “Mercantilism.”

14 “1651 — Navigation Acts,” Stamp Act History, accessed December 6, 2023, http://www.stamp-act-history.com/timeline/27/.

get their economy back on track, they concluded that their amount of imports must surpass their amount of exports.15 That is why they passed The Navigation Acts. They allowed Britain to be more in control of Colonial America because it didn’t allow America to trade with anyone but England. The Thirteen Colonies were loaded with valuable resources that were in demand in Europe. But because of the Navigation Acts, they were only allowed to trade with England. Not only did it put England in control and increase their profits, but it also limited the UK’s trade competition with other European countries and prevented any growth or success for the colonies in terms of trading.16 The British made sure the Navigation Acts prevented the colonies from receiving a large profit from their trade by enforcing many rules about shipping and trade, setting taxes on many items in order to acquire wealth as a European country, and limiting attempts at manufacturing because if the colonies had factories, they would not need any goods from England and the UK would no longer be exporting more than they were importing.17 Additionally, the Navigation Acts differentiated between the goods imported from other European countries and from English colonies in America, Asia, and Africa. It stated that goods from other European countries could ship their goods in British ships or the vessel of the country from which the products were from, but English colonies must ship resources on English ships only. If the “New Land” sent their crops on ships of different countries, England couldn’t control the price. And that was the only goal of the kingdom, to make money.18 One of the first Navigation Acts was passed in 1651 and it was called the “Navigation” Act because it was a law that regulated trade, or navigation. In this law, it emphasized that no foreign ships were allowed in Colonial ports from the 1650 ordinance and that British vessels must include a crew of 50% Englishmen. Not only was England limiting who the colonies were trading with, but they also created a law stating that only English ships could sail into colonial ports. This shows just how nervous the English are about their competition with other European countries. They are guarding colonial resources like it was gold. But in the 17th century these things could be considered just as valuable as gold because they were necessities. This exemplifies how the Navigation Acts were not only created to make a profit for the UK, but they were also set in place to preserve the British economy when the Netherlands were their biggest competition in the trading world. Although it is a relatively small country, it historically had a lot of dominance. And Holland dominated the trade in the 17th century, so they were a nation to look out for.19 The first great Navigation Act mentioned above was written in response specifically to the Dutch, but quickly grew into legislation aimed towards all of England’s rivals. The British didn’t want any other nations stealing their resources.20 However, the next Navigation Act of 1660 was more universal. It listed certain products that had to be shipped directly to England via English shipping before getting shipped to other foreign ports. All other goods could be sent directly. These goods included sugar, indigo, tobacco, rice, and molasses.21 And starting in 1664, English colonies

15 “1651 — Navigation,” Stamp Act History.

16 “Mercantilism,” American History, last modified 2023, https://americanhistory.abc-clio.com/Topics/Display/1183173?cid=41 &sid=1183173.

17 The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica, “The Navigation,” Britannica.

18 The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica, ed., “The Navigation Acts,” Britannica, last modified October 10, 2023, accessed November 9, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/event/Navigation-Acts.

19 “1651 — Navigation,” Stamp Act History.

20 The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica, “The Navigation,” Britannica.

21 The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica, “The Navigation,” Britannica.

had to get European goods from English ships exclusively.22 Following Navigation Acts a couple decades later stated:

Be it enacted, . . . that after the five and twentieth day of March, one thousand six hundred and ninety-eight, no goods or merchandises whatsoever shall be imported into, or exported out of, any colony or plantation . . . or shall be laden in, or carried from any one port or place in the said colonies or plantations to any other port or place in the same, the kingdom of England, dominion of Wales, or towns of Berwick upon Tweed,...23

As exemplified above, the rules about shipping and trade only got stricter over time as the threats towards England grew stronger. However, when the Navigation Acts started to limit the colonist’s rights to such a great extent, they started to get mad.

The Colonists, angered by this new legislation, were quick to retaliate. They became resentful of the laws passed in the Navigation Acts and the taxes they had to pay due to them.24 In the Magna Carta, it states that no taxation should take place without representation. The Thirteen Colonies had no one in Parliament speaking for them, and they found it unjust that England was demanding money from them regardless. They decided in the House of Burgesses that they were not going to sit still while England stripped their rights from them. Instead of acquiescing to the new statutes, they would put up a fight. Colonists were also upset at the new laws because they were not getting as good of a price for their products as they would receive from the Dutch. Keen on getting the best prices, the colonists tried to be noticed.25 And it worked. In 1651, recently after the first Navigation Act was passed, troops were sent down to the rebelling colonies of Virginia and Barbados. The colonies were upset at the new legislation. They didn’t want their profit limited because the English wanted more money.26 Although the protests were shut down, the colonists continued to smuggle goods and trade with Holland because there were no officials present to catch them.27 But, over time, the first Anglo-Dutch war in 1652 began because the English were angered that the Dutch were still trading with English colonies and ignoring the new legislation. In the end, the Dutch finally accepted the new laws. But over the next 100 years, the colonists continued to rebel against the unfair laws.28

The Navigation Acts were the first set of laws set in place of many that enacted unfair taxation upon the Thirteen Colonies. Most Americans were farmers and self-sufficient. They started to realize they didn’t need to rely on the British to ship them any overpriced goods. They began to make everything themselves.29 However, it didn’t start this way. Merchants were the first in the colonies to disapprove of the Mercantilist ways of Britain. They were the ones witnessing the Navigation Acts everyday as they negotiated for the goods that recently came off the ships. Although the merchants were not the first to realize how unfair these acts were, they were the first to come up with the idea of revolution.30 And the Navigation Acts were not the

22 The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica, “The Navigation,” Britannica.

23 “Navigation Acts,” Digital History, accessed December 22, 2023, https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=3&psid=4102.

24 “1651 — Navigation,” Stamp Act History.

25 “1651 — Navigation,” Stamp Act History

26 “1651 — Navigation,” Stamp Act History

27 “1651 — Navigation,” Stamp Act History

28 “1651 — Navigation,” Stamp Act History

29 U.S. Department of State, “The U.S.,” USEmbassy.gov.

30 Mark Mayo Boatner, Encyclopedia of the American Revolution (New York: Stackpole Books, 1994), 701.

only laws that restricted trade and increased taxes in the colonies. After events that took place in the 1760s, merchants were forced to choose where their loyalties would lie with the war on the horizon. Did it lie with the colonies, who were showing more and more signs of growing independence from European rule? Or did it lie with England, who was predicted to win and convince the merchants of this with conservative ideas?31

The impact the Navigation Acts had on Colonial America was immeasurable. Not only did they anger the colonists, but they were also part of the reason the Thirteen Colonies desired their own government. Mercantilism was a common concept in the 17th and 18th centuries, and this was the practice that led to the creation of the Navigation Acts. England thought it was okay to set in place as much legislation as they pleased because they believed that they could do whatever they wanted with their power. This is a common misconception from officials. They will do horrendous things in order to obtain more dominance. They believe that because they have superiority, they can do whatever they wish to those who don’t. In the case of Britain, the people making laws for the colonies were not elected by the colonists themselves. After the revolution, people in the United States voted for all their politicians, but that is not the case everywhere in the world. Is it fair for some countries to have laws made for them by legislators whom they did not choose? In the case of the “New Land,” when the colonists did not determine their lawmakers, the statesmen selfishly created statues instead of what was best for the majority of the population because they did not have to rely on the approval of the nation to get reappointed to their positions. Should people with this insensitivity and opportunism be creating regulation?

Bibliography

Boatner, Mark Mayo. Encyclopedia of the American Revolution. New York: Stackpole Books, 1994.

The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica, ed. “The Navigation Acts.” Britannica. Last modified October 10, 2023. Accessed November 9, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/event/ Navigation-Acts.

This source is a web page with lots of historical information on it. I am using an article called The Navigation Acts. Britannica has been spreading information for over 250 years. They always use trusted sources and make sure to have correct information in their articles.

Koot, Christian J. “Smuggling in Early America.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia. Last modified January 4, 2016. Accessed December 10, 2023. https://oxfordre. com/americanhistory/americanhistory/view/10.1093/ acrefore/9780199329175.001.0001/acrefore9780199329175-e-263#:~:text=Smuggling%20in%20 colonial%20British%20America,limited%20where%20 one%20could%20trade.

“Mercantilism.” American History. Last modified 2023. https://americanhistory.abc-clio.com/Topics/ Display/1183173?cid=41&sid=1183173.

This source is a database that specializes in American History. I am using a source about Mercantilism. This source has many great articles that are useful to my topic. Also, it has only factual information because it uses trusted sources to get their information.

“Navigation Acts.” American History. Last modified 2023. https:// americanhistory.abc-clio.com/Search/Display/298791.

“Navigation Acts.” Digital History. Accessed December 22, 2023. https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook. cfm?smtID=3&psid=4102.

This website has primary sources. This primary source is a copy of all the Navigation Acts from 17th-century England.

Seavoy, Ronald E. An Economic History of the United States: From 1607 to the Present. London, England: Routledge, 2006. This book is about the economy from 1607 to the present. I am using the information about from 1607 until the end of the American Revolution. The author, Ronald E. Seavoy, is a professor emeritus at Bowling Greens State University in Bowling Greens, Ohio. He has written many other books as well.

Sherman, Roger. Letter, “Alexander Hamilton’s Financial Program,” 1790. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.digitalhistory. uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=3&psid=268.

This is a letter authored by Roger Sherman to Governor Samuel Huntington. Roger Sherman was a congressman from Connecticut who wrote the Connecticut Compromise at the Constitutional Convention. Governor Samuel Huntington was the governor of Connecticut from 1786 until his death in 1796. He was also the former president of the Continental Congress from 1779-1781 and a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Neither of them were founding fathers but they were both very significant.

Simpson, Stephen D. “Understanding Finance vs. Economics: What’s the Difference?” Investopedia. Last modified September 13, 2023. Accessed October 30, 2023. https://www.investopedia. com/articles/economics/11/difference-between-finance-andeconomics.asp.

“1651 — Navigation Acts.” Stamp Act History. Accessed December 6, 2023. http://www.stamp-act-history.com/timeline/27/.

Trevino, Marcella Bush. “Labor and Employment in the Colonial and Revolutionary Era.” In Labor and Employment in the Colonial and Revolutionary Era. N.p.: Facts On File, 2016. http://online.infobase.com/Auth/ Index?aid=17980&itemid=WE52&articleId=396927. Infobase Learning is a database with lots of information. I am using this part of the database for American history. The article I am taking notes from is about Labor and Employment. This is very important for the economy because changes in employment affect the economy.

University of Minnesota. “Explaining Economic Sectors.” Carlson School of Management. Accessed November 1, 2023. https://carlsonschool.umn.edu/degrees/public-and-nonprofitmanagement/explaining-economic-sectors.

U.S. Department of State. “The U.S. Economy: A Brief History (Outline of the U.S. Economy).” USEmbassy.gov. Accessed November 1, 2023. https://usa.usembassy.de/etexts/oecon/ chap3.htm.

,

.

Aubrey Goldstein ’28

Kamsiyo Nwabueze-Pryor ’28

Lake Stanford ’28

Joonkyu Shim ’28

Madison Lee ’28

Rowan Kuick ’28

Tamara Regular ’28

The 18th century represents a dark period in American history when the institution of slavery thrived, and the exploitation of enslaved Black women flourished. The cruel realities endured by Black women during this time were not only a consequence of their enslavement but were also magnified by both their race and gender, perpetuating a cycle of inequality and suffering. Beyond the physical captivity, these women endured a complex oppression that not only involved grueling labor but also made them victims of sexual violence. The harsh reality of this oppression becomes evident when one reflects on how the clothing worn by enslaved Black women served as a physical manifestation of their fragile existence. The clothes they wore were not just rags or pieces of fabric used to cover their bodies; they represented a system that dehumanized and abused them. During the 18th century, an enslaved Black woman’s gender and race primarily affected the way she lived and thrived in an illiberal society. Understanding the exploitation of enslaved Black women during the American colonial era requires a closer look into the sweat of their daily labor, the sexual abuse they endured, and the clothing they wore that bound them to such a harsh life.

However, before any discussion regarding the exploitation of enslaved Black women is made, one must first consider that the racial stereotypes and discriminatory practices against enslaved Black women during the colonial era were the underlying causes of their mistreatment. The widely accepted racist ideas of Antebellum white slaveholders led them to think of their enslaved people as both biologically and culturally inferior. Due to their superiority complex, slaveholders often whipped and physically mistreated enslaved women under their supervision.1 In addition to the racist beliefs they held, slaveholders also created various stereotypes about enslaved black women. One such popular stereotype was the “Mammy” caricature. The mammy caricature depicted enslaved Black women as enjoying their servitude, being physically unattractive, and only fit to be domestic workers.2

In contrast to the mammy caricature, slave owners also created a more promiscuous stereotype of enslaved Black women: the “Jezebel” figure. The Jezebel caricature was used during slavery to justify a slaveholder’s objectification and sexual exploitation of enslaved Black women.3 The Mammy and Jezebel caricatures, along with various other derogatory stereotypes that plagued enslaved Black women, heavily influenced how the rest of the white population during the Antebellum period perceived and treated Black women. Sadly, these caricatures endured for decades even after colonial times. Even today, Black women are oftentimes stereotyped as being hypersexual, unattractive, or possessing some other demeaning attribute. With racial stereotyping forming the underlying cause of discrimination against Black women, white slave masters subjected Black women to harsh labor conditions. Enslaved women were often forced to work in the fields from sunrise to sunset where they endured physical and emotional abuse. On larger farms and plantations, for example, women were forced to perform tasks like hoeing and ditching entire fields. These were the most exhausting and uninteresting forms of fieldwork.4 Slaveholders also held enslaved women accountable for

1 LDHI, “Hidden Voices: Enslaved Women in the Lowcountry and U.S. South,” LDHI, accessed November 27, 2023, https://ldhi.library.cofc.edu/exhibits/show/hidden-voices/enslaved-womens-work.

2 LDHI, “Hidden Voices,” LDHI.

3 LDHI, “Hidden Voices,” LDHI.

4 Jennifer Hallam, “The Slave Experience: Men, Wom-

cleaning and tidying communal areas like stables and expected them to spread manure as a fertilizer.5 Moreover, slave owners frequently questioned how much time off enslaved women needed to adequately take care of their families and children. When not offered any downtime by their slaveholders, enslaved women had to bring their children with them to the fields and strap them to their backs as they worked tirelessly without any pay.6

Black women’s exploitation extended beyond the fields. In many instances, the labor performed by enslaved women was prolonged and complicated. For example, many enslaved women began to work for slaveholders at a very young age. There was little free time for enslaved women to rest, given that most women worked for their masters five to six days a week. This included keeping the owner’s homes clean, cooking food, and washing their clothes.7

In short, enslaved women were expected to work tirelessly, both in the fields and in the house. The slave masters did not care about these women’s well-being and exploited them for their free labor. Long days performing menial, exhausting tasks, sometimes in the hot, baking sun, was what many Black women had to endure. After working prolonged, hard days for the slaveholders, these women had to care for their own families, which was often a physical and mental challenge due to exhaustion and limited time availability. But if they did not work hard enough to meet the expectations of their enslaver, they would oftentimes be taken advantage of by being sexually or physically assaulted, as a form of punishment. Unfortunately, this possibility became a reality for many enslaved Black women.

Indeed, as the slave population in America grew larger, slaveholders began to consider enslaved Black women primarily as reproducers of a valuable labor force rather than merely a part of the labor force. The sexual exploitation of Black women extended from sexual gratification of their white slaveholders to include reproducing offspring that would expand their workforce. Though slave owners valued enslaved women as laborers, they were also well aware that female slaves could be used to successfully reproduce new labor (more children who would grow up to be slaves) by continuing their role as full-time mothers.8 This presented slaveholders with a dilemma because West African women usually had some prior agricultural experience (like growing tobacco and rice) which could be used to the slaveholders’ benefit. But these women also could be raped or otherwise made to have children, which would produce more slaves for the slave owner and ultimately make him richer.9

In 1756, Reverend Peter Foutain of Charles City County, Virginia, stated that Black females were “far more prolific than... white women.” This form of racial stereotyping made enslaved women extremely vulnerable to physical assault.10 Many white enslavers raped Black women for sexual pleasure, as well as for their ability to produce children who would become slaves and ultimately increase their wealth. Instead of perpetuating the stereotype that all enslaved Black women were unattractive and were only fit to be domestic workers, they now were feeding into the stereotype that they were promiscuous and desired sex. This form of physical exploitation was pervasive en & Gender,” Slavery and the Making of America, accessed November 27, 2023, https://www.thirteen.org/wnet/slavery/ experience/gender/history.html.

5 Emily West, Enslaved Women in America: From Colonial Times to Emancipation (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2017), 29

6 West, Enslaved Women, 28.

7 LDHI, “Hidden Voices,” LDHI.

8 West, Enslaved Women, 28.

9 West, Enslaved Women, 29

10 West, Enslaved Women, 31.

throughout the Antebellum South.

In addition to labor and sexual exploitation, clothing was another form of exploitation that enslaved Black women were forced to endure. While these women often knitted or otherwise made beautiful garments for white women and their children, the fabrics that enslaved Black women wore themselves offered minimal protection from the weather and had to be inexpensive and easy to make.11 Their clothing was so cheap in quality that it often disassembled or tore within weeks. As a result, enslaved women often borrowed clothing from one another or even stole clothing from the slave master’s house. They did this to give themselves or their families warm, sustainable garments, and sometimes, to blend into the free population.12 Enslavers also made enslaved women wear poor, rugged clothing to symbolize a Black woman’s low status and to cultivate racial stereotypes depicting Black women as inferior. Therefore, one reason why enslaved women wanted to steal white people’s clothes was because they wanted to appear as free Black people with increased status.

Despite being subjected to clothing exploitation, many enslaved women nevertheless tried to continue to be connected to their former culture by wearing West African garments. Enslaved women working in slaveholders’ homes were expected to cover their heads with lightweight white caps, which other members of the household also wore. However, to continue the West African tradition, many enslaved women also chose to wear brightly colored head wraps that surrounded their heads and were secured with knots and tuckings.13 They also sometimes wore Cowrie shells in their hair; shells were very expensive and far more valuable than money. These cowrie shells also appeared in spirit bundles as parts of clothing and jewelry, implying their use as amulets.

Black women not only wore these West African garments to remain connected with their former cultures, but they also wore the garments as a form of resistance against enslavement.14 Enslaved Black women despised their status as slaves but were able to feel proud about and connect to their former West African heritage when they wore their West African headdresses. Culturally significant garments like this made these Black women feel strong and empowered and signaled to the slaveholders that Black women shouldn’t be taken advantage of or misjudged just because of their torn and cut clothing.

During the 18th century, the exploitation of enslaved Black women through their gender and race greatly influenced the way they survived and flourished in a prejudiced society. Enslaved women were exploited in numerous ways and were expected to address the needs of others to the detriment of caring for themselves and their families. They worked extremely hard, both in the house and in the field, and did whatever they were commanded to do, withstanding both physical and emotional abuse. They were oftentimes raped through their shabby

11 Daina Ramey Berry and Deleso A. Alford, eds., Enslaved Women in America: An Encyclopedia enhanced credo edition ed. (Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2012), 34 and 35.

12 Katherine Gruber, ed., “Clothing and Adornment of Enslaved People in Virginia,” Encyclopedia Virginia, last modified December 7, 2020, accessed November 5, 2023, https:// encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/slave-clothing-and-adornmentin-virginia/.

13 Gruber, “Clothing and Adornment,” Encyclopedia Virginia.

14 Smithsonian and National Museum of African American History and Culture, “Cowrie Shells and Trade Power,” National Museum of African American History and Culture, accessed November 15, 2023, https://nmaahc.si.edu/cowrie-shells-and-trade-power#:~:text=Europeans%20in%20the%20 16th%20century,at%20their%20use%20as%20amulets.

clothing and were physically assaulted by their masters for punishment as a means to increase their profit. But still, an enslaved Black woman was able to overcome these acts of exploitation non-violently and create her own peace by wearing and displaying garments that were distinct to her West African culture. Given all that these enslaved women endured, we should respect and admire their ability to overcome such incredible hardships and ultimately produce future generations of beautiful, strong, educated, proud, and free Black women.

Bibliography

Berry, Daina Ramey, and Deleso A. Alford, eds. Enslaved Women in America: An Encyclopedia. Enhanced Credo edition ed. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2012.

Gruber, Katherine, ed. “Clothing and Adornment of Enslaved People in Virginia.” Encyclopedia Virginia. Last modified December 7, 2020. Accessed November 5, 2023. https:// encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/slave-clothing-andadornment-in-virginia/.

Hallam, Jennifer. “The Slave Experience: Men, Women & Gender.” Slavery and the Making of America. Accessed November 27, 2023. https://www.thirteen.org/wnet/slavery/experience/ gender/history.html.

LDHI. “Hidden Voices: Enslaved Women in the Lowcountry and U.S. South.” LDHI. Accessed November 27, 2023. https:// ldhi.library.cofc.edu/exhibits/show/hidden-voices/enslavedwomens-work.

Smithsonian, and National Museum of African American History and Culture. “Cowrie Shells and Trade Power.” National Museum of African American History and Culture. Accessed November 15, 2023. https://nmaahc.si.edu/cowrie-shellsand-trade-power#:~:text=Europeans%20in%20the%20 16th%20century,at%20their%20use%20as%20amulets.

West, Emily. Enslaved Women in America: From Colonial Times to Emancipation. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2017.

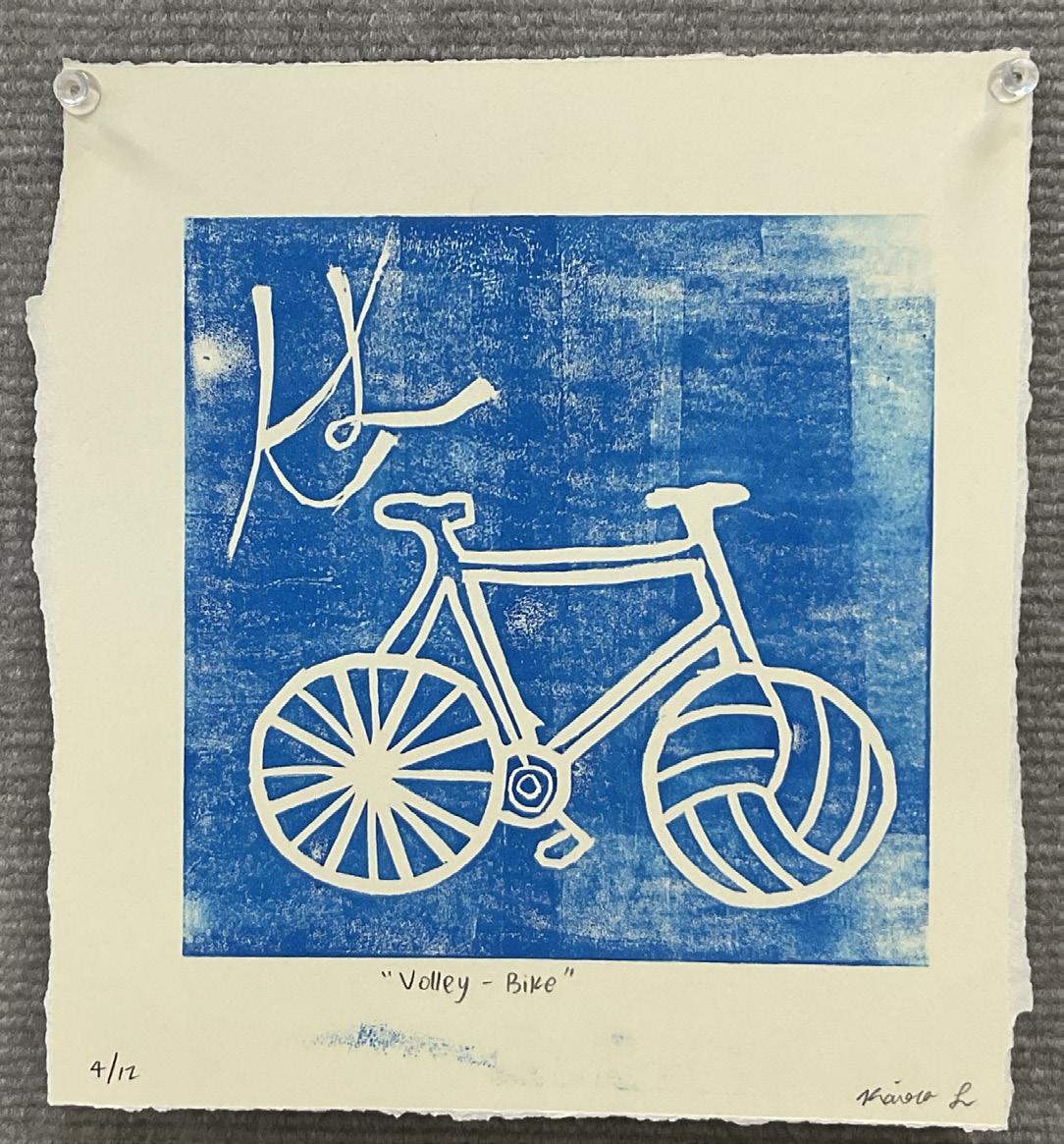

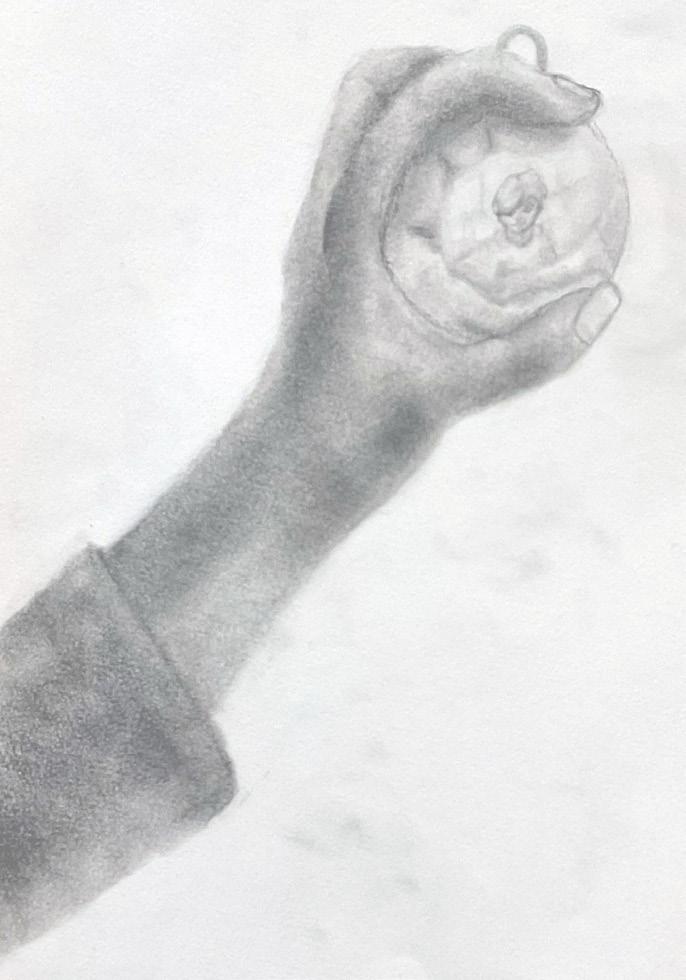

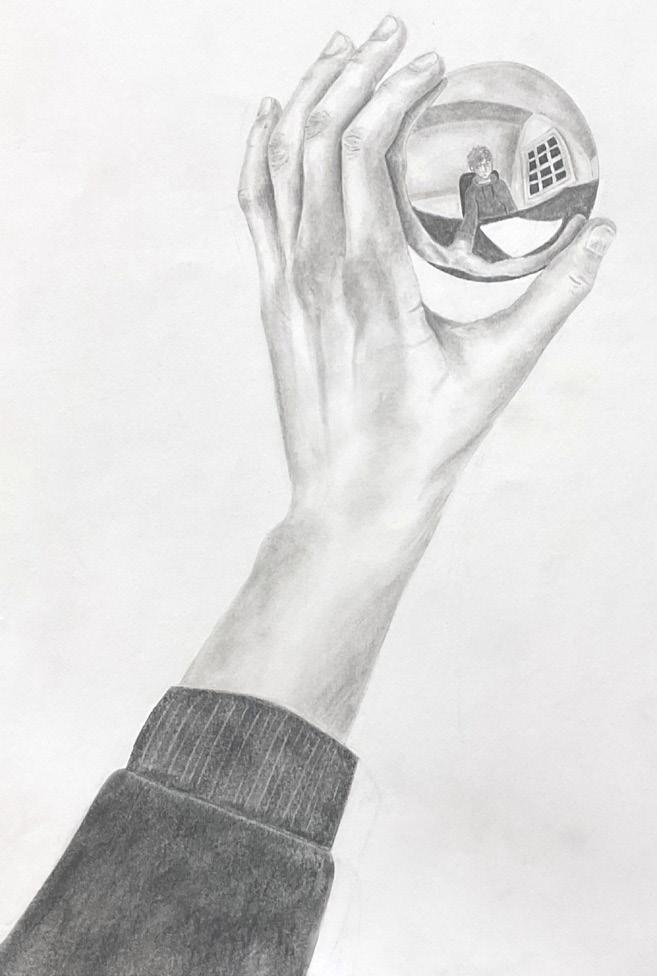

Oliver Hejna ’28

Oliver Hejna ’28

Music is a common form of expression that has been used since the beginning of history. It is a beautiful way to express emotions, ideas, beliefs, and opinions. From pop to rap to heavy metal, there is a form of music for everyone. Often, different styles tend to combine and influence each other to create new styles, and every group of people in history has influenced each other’s music in many ways. Music is an irreplaceable part of a large amount of cultures, some of which were the colonists, Native Americans, and the enslaved population of Colonial America. They all benefited greatly from having music in their lives, and the music of their culture developed thanks to the interaction between these groups. Music was important and influential for colonists, enslaved people, and Native Americans during the colonial era.

Music was undeniably influential for all people in the colonial era, but it was instrumental in keeping the spirits of enslaved people high by providing them with an outlet to express themselves in times when the quality of treatment from their slave owners was at a disgusting low. Music was exceptionally important to the progression of enslaved people’s history not only because of its use for emotional expression, but also for communicating with one another while working. This method of communication was called a field holler, which was sung by a single person at a time and was used to communicate across fields. Another example of this was referred to as work songs, which were sung by groups of enslaved people working in fields to align their pace.1 This provided comfort and something to pass the time, and none of the workers could be too slow or too fast if they were all working in concert. Coming from a musically diverse background, the way African-American enslaved people sang their songs was difficult to describe in a proper musical score. Vocalizations were described as “odd turns made in the throat” by European observers, and irregular rhythmic patterns that were unheard of in European and English music made writing it down a challenge. The difficulty of recording the music on paper made it all the more unique and expressional.2 While listening to music that would have been sung in the fields by the enslaved people, lots of passion and spirit can be heard. In addition to most of the songs being call-and-response, whoops, woos, and hollers are interjected into the music.3 The emotion and passion of the music they were creating allowed them to express their thoughts where they otherwise couldn’t. The enslaved people sang about their working and living conditions and the way they were treated. For example, some lyrics like “We cook the meat, and you give us the skin,” and “We bake the bread, and you give us the crust,” and “We beat the corn, and you give us the husk” are indicative of their treatment. The lyrics describe if they were to cook and bake for their owners, they would get scraps left behind for a meal, or beating corn and only receiving the husk in return for their work.4 One thing that can be said about the music of the enslaved population was it was full of life. It was one of the few ways they could have fun and express themselves in such difficult times. Music held great importance to the enslaved people of the American Colonies because of the uniqueness, expressionism, and passion that is consistent throughout all examples that have been recorded. Another important part of the use of music for enslaved people was that it was crucial for the enslaved people who escaped

1 Mintz S and McNeil, “Music under Slavery,” Digital History, last modified 2018, accessed November 3, 2023, https://www.digitalhistory. uh.edu/era.cfm?eraID=6&smtid=6

2 S and McNeil, “Music under,” Digital History.

3 From Ear to Ear, performed by Kathaleen Getward-Holiday and Greg James, produced by Rex Ellis, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2006, compact disc

4 From Ear to Ear.

slavery. Different songs had different meanings when it came to communication between the enslaved. A song called “Wade in the Water” would be used to tell enslaved people who were escaping to stay in the river to travel, in order to avoid search dogs. Lyrics such as “Wade in the water, children” and “Man went down to the river” indicated to the enslaved people that this really meant to travel by river.5 Another song called “Sweet Chariot” was sung by an enslaved person to let others know an escape was being done soon. Some example lyrics are “Swing low, sweet chariot, Coming for to carry me home…Tell all my friends I’m coming too.” Here, the enslaved sang about waiting for the escape opportunity to arrive, disguised as a chariot in the lyrics.6 The most notable and recognizable of these songs was “Follow the Drinking Gourd.” It contained a set of instructions with the information necessary for the enslaved people to find their way to a safe house. For example, the lyric “When the sun goes back and the first quail calls” is an indication of spring, when the quails start singing. “Follow the Drinking Gourd” itself is code for the big dipper constellation that guided the escaped enslaved individuals. Other lyrics such as “Now the river bed makes a mighty fine road” and “Dead trees to show you the way” are a signal of location, saying that the escapees should use the river as a path so the search dogs cannot find their scent.7 However, looking past the audible lyrics that had a hidden meaning in the songs, the alternative was field hollers. They were a key method of communication between enslaved workers, most commonly used in fields that seemed like random vocalizations, but had meanings that ranged from greeting each other to warning runaway enslaved people to communicating escape opportunities.8 Music was tremendously important to the freedom of the enslaved people because it helped them get vital information concerning escape.

Music served many purposes for the colonists. It was most notably used for entertainment and religious services, but was also used for social functions such as ceremonies and dancing. It was also used for theater and the military. Several other forms of music were ballads, carols, folk songs, hymns, and ribald songs.9 A very widespread use for music, especially among Anglicans, was for religion. Organs and choirs were slowly introduced to churches,10 but originally, most were not open to instrumental music in church, with only the use of psalms. However, because these psalms were not written down, the attendants of church had to go by ear, resulting in an unpleasant array of sounds. Soon, though, most churches had professional musicians teaching choirs and other musicians.11 After listening to an example of colonial music, it can be said that it was precise. Everyone singing has a clear role that they stick to, sounding much like church choirs today.12 Music traveled from England with the colonists. Along with being used in church, people sang for their own entertainment. Sometimes they sang madrigals, other times they sang along with lutes, virginals, violins, and trumpets.13 Music was essential to English and European churches, and people’s entertainment.

The interaction of these three groups of people caused their

5 Wade, “Signal Songs,” Discovery Theater.

6 Wade, “Signal Songs,” Discovery Theater.

7 Wade, “Signal Songs,” Discovery Theater.

8 Wade, “Signal Songs,” Discovery Theater.

9 McNeil and Mintz S, “Music under Colonial Era,” Digital History, last modified 2018, accessed November 3, 2023, https://digitalhistory.uh.edu/ era.cfm?eraID=2&smtid=6.

10 McNeil and S, “Music under,” Digital History.

11 Clint Twist, ed., Colonial America (Danbury, Conn.: Grolier Educational, 1998), 79.

12 McNeil and S, “Music under,” Digital History.

13 Twist, Colonial America, 79.

styles of music to combine and create new styles of music. For example, the arrival of Europeans in North America not only influenced the people, but it also influenced the music. The Native Americans had a strong culture that persevered through European influence. However, they did pick up some aspects of European music. One of these changes was that they adapted European musical forms and ways of keeping themes and time.14 While the European influence had a profound effect on the Native Americans, they, in return, also had some influence on the Europeans. Some Native Americans converted to Christianity, and became closely tied with music in French and Spanish churches where they were allowed to compose and perform church music.15 Some of the music that the Native Americans wrote is visible in church music today, while it may be subtle. Contrary to the indigenous music of the Native Americans, the music style brought from Africa by the enslaved people was heavily influenced by popular white music while still retaining its own unique qualities. This music style developed into what we now call gospel and blues.16 Music was not only important and influential to the people of the colonial era, but its influence from one type of music to another also created the music that is familiar in the present day. Music was of great value to the people in colonial America. It not only made the quality of life better, but the development of music as a whole benefitted from the interaction of these people. Music made otherwise unbearable lives much more tolerable, such as in the enslaved worker’s case. Music was an integral part of a culture that helped the Native Americans worship and practice their religion, and it became an irreplaceable part of Christian churches throughout the development of the colonies. In the present day, music plays a predominant role in the daily lives of most people, whether it is noticed or not. For example, most people notice the presence of music in advertisements only when there is a lack of it. For many, music is a job, a pastime, or a passion. It is important to appreciate the beautiful form of expression that has been carried on for all of human history. Often, as a society, we take for granted the gifts we have, and making sure those subjects are discussed makes it all worthwhile.

Bibliography

Apold, Juliette. “Appreciating Native American Music.” Library of Congress Blog. Last modified November 4, 2021. Accessed November 23, 2023. https://blogs.loc.gov/ nls-music-notes/2021/11/appreciating-native-americanmusic/#:~:text=Music%20serves%20as%20a%20 medium,%2C%20moral%2C%20and%20cultural%20events.

From Ear to Ear. Performed by Kathaleen Getward-Holiday and Greg James. Produced by Rex Ellis. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2006, compact disc. This is my primary source.

Hildebrand, David K. “Early American Music.” Mount Vernon. Last modified September 18, 2001. Accessed November 23, 2023. https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/colonialmusic-institute/essays/early-american-music/.

While this source was written in 2001, it has updates, the most recent of which was in January of 2023.

Jennings, Matthew. “Music.” In Encyclopedia of Native American History, Volume 2. N.p.: Facts On File, 2011. http://online.infobase.com/

14 Matthew Jennings, “Music,” in Encyclopedia of Native American History, Volume 2 (n.p.: Facts On File, 2011), African-American History.

15 Jennings, “Music”.

16 Clint Twist, ed., Colonial America (Danbury, Conn.: Grolier Educational, 1998)

Auth/Index?aid=17980&itemid=WE01&articleId=359394.

This source is a book source that I found in a database. I hope that this source can help me illustrate some aspects of Native American Music. I also hope to show what aspects of European music the Native Americans adopted as well.

Mari, Adriana. “Follow the Drinking Gourd.” Genius. Accessed November 17, 2023. https://genius.com/Richie-havensfollow-the-drinking-gourd-lyrics.

This website will allow me to cite the lyrics of an old song originating in Colonial america.

McNeil, and Mintz S. “Music under Colonial Era.” Digital History. Last modified 2018. Accessed November 3, 2023. https:// digitalhistory.uh.edu/era.cfm?eraID=2&smtid=6.

The title of this source is what tabs the website is on- not the actual name. This source may help me describe what purpose music served for the colonists. I hope that in my body paragraphs, this source can help me illustrate how music was a big part of religion and a part of their social lives.

S, Mintz, and McNeil. “Music under Slavery.” Digital History. Last modified 2018. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www. digitalhistory.uh.edu/era.cfm?eraID=6&smtid=6.

The title of this source is simply what tabs the website is on- it is not the actual name. I hope this source will help me describe what kind of music African American enslaved people sang, how they sang it, and for what purpose.

S, Mintz, and McNeil S. “Music under the First People.” Digital History. Last modified 2018. Accessed November 25, 2023. https:// www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/era.cfm?eraID=1&smtid=6.

Twist, Clint, ed. Colonial America. Danbury, Conn.: Grolier Educational, 1998.

This is a book source. I hope this source will help me answer what purpose music served to the enslaved and how white music affected the African culture that turned into slave songs.

Wade, Phyllis. “Signal Songs of the Underground Railroad with Dr. Phyllis Wade.” Discovery Theater. Accessed November 9, 2023. https://discoverytheater.org/forms/guides/2017/ feb/Signal%20Songs%20of%20the%20Underground%20 Railroad%20Learning%20Guide.pdf.

This is a PDF I found online- I wasn’t sure what kind of source it was meant to be listed as. I hope this source will help me describe different songs of the enslaved people, and how they helped people escape. Another thing that may be worth mentioning in my paper is how the songs were used by the underground railroad. The author completed a bachelor’s degree in voice at Roberts Wesleyan College.

Aubrey Goldstein ’28

Georgia Aitken ’28

What caused the law in the United States to look the way it does today? During colonial times, during the beginning of the revolution and the forming of a new nation, the trials and lives of many people had lasting impacts on the legal system. They caused changes that helped form and reform the legal system that is enforced today. Some of these trials affected how strict laws were, how harshly religious laws were enforced, and how all different people were treated both in the courthouse and in daily colonial life. Anne Hutchinson, Elizabeth Key, and Mary Dyer’s trials, as well as the Salem Witch trials and the Boston Massacre trials, were turning points in the legal system’s perception, enforcement, and impact in Colonial America.

The life and trial of Anne Hutchinson show how laws around religion were enforced and impacted law in Colonial America, changing the religious lives of many. Hutchinson was born in England in 1591 to a father who was a Puritan minister, who was sentenced to three years of house arrest for criticizing the church the year she was born.1 As a result of Hutchinson’s living situation, she likely had a lot of time to read and learn about Puritan laws and why her father was punished. Hutchinson went to Boston in 1634 where she, six weeks later, was given a membership to the Boston church. In this Puritan community, religion was very important and strict.2 In Boston, women were banned from church service participation, not allowed to be ministers, not allowed to vote on church issues, not allowed to talk in church, and were forced to enter the church through a separate door. Hutchinson started calling herself an interpreter of the Bible and influenced many people, mostly women, in women’s religious study groups.3 This is an example of how the Puritan religion was very important and influential in Boston and the laws concerning it affected Hutchinson and forced her to find a way around it. In 1636, seven ministers called her to a meeting where they demanded her to share her views on religion. Later, ministers identified 82 errors found in the meeting with Hutchinson. She was consequently banned from leading religious discussion groups. In November 1637, Hutchinson’s Trial began. There were 9 magistrates and 31 deputies of Massachusetts’ General Court.4 People were very against Hutchinson’s sharing of her ideas and took her to court for doing so. After many hours in court, Hutchinson was banished for not being a woman “fit” for society and was to be imprisoned until her banishment. 5 After the verdict was given, Hutchinson had to stay in her house for months until she, her family, and many others left for Rhode Island where they founded Portsmouth.6 This demonstrates how important laws about women’s roles in religion were, and how severe the results were. Plus, Hutchinson’s influence was demonstrated by how many people left for Rhode Island. Hutchinson’s trial gave her a chance to speak up to her whole colony and led to the beginning of a nation in which liberty would have a large and important meaning. It resulted in more religious freedom in Massachusetts and, eventually, helped guarantee religious freedom for all people.7 Anne Hutchinson’s trial changed how people felt about their laws and started the influence of liberty during the start of a new nation.

The life of Elizabeth Key shows how impactful slave law was 1 History.com, ed., “Anne Hutchinson,” History, last modified June 23, 2023, https://www.history.com/topics/colonial-america/Hutchinson-hutchinson.

2 Douglas O. Linder, “The Trial of Anne Hutchinson,” Famous Trials, https://www.famous-trials.com/hutchinson/2395-hutchinson-1637-account.

3 Linder, “The Trial,” Famous Trials.

4 Linder, “The Trial,” Famous Trials.

5 Linder, “The Trial,” Famous Trials.

6 History.com, “Anne Hutchinson,” History.

7 Linder, “The Trial,” Famous Trials.

and her trials were a major turning point for laws concerning enslaved people. Key sued for her freedom from slavery and won, becoming the first woman of African ancestry in the American colonies to do so. She won freedom for her sons and herself on July 21, 1656, in Virginia, suing on the fact that she was a baptized Christian and her father was an Englishman.8 Key’s trial made her a huge historical figure as the first woman to stand up against enslaved laws. Key was born in Virginia; her mother was a slave and her father, Thomas Key, was a white Englishman who was a burgess in Virginia’s colonial assembly.9 Her father arranged for her godfather, Humphrey Higginson, to have possession of her for nine years, requiring him to be her guardian, treat her like a family member, and free her at the age of 15. However, when her father died, Higginson sold her to Colonel John Mottram, where she had to serve nine years before being released. She was taken to Northumberland County, where Coan Hall, a plantation, was built.10 The legal system in Colonial America restricted what Key could do because of the laws about who was considered a slave. When her father died, laws about enslavement foiled his plans for her to live freely. Key’s lawsuit was one of the earliest lawsuits for freedom filed by someone of African ancestry in the American colonies. With her husband, William, as her lawyer, she used an English law stating that if a child had a free father, the child was free too, and Key was given freedom.11 However, the decision was soon overturned by the Virginia General Court. Key, though, wouldn’t back down and fought to be heard by the Virginia General Assembly, and Key, finally, won her freedom.12 This shows how much restraint the legal system had on the enslaved and how hard it was to pursue freedom as an enslaved person, even when her father was white and she was a baptized Christian. In 1662, as a result of Key’s case, a law was passed clarifying that a child of African descent’s freedom, or lack thereof, would be decided by the condition of their mother, rather than English law, which stated it was based on the condition of the father. This ensured that all children of women slaves could be kept for labor unless distinctly freed; additionally, this caused some fathers to not acknowledge their children as their own, supporting them, arranging for apprentices for them, or emancipating them.13 Key’s trial affected the lives of future enslaved people; although the results weren’t exactly helpful for the enslaved, she showed that freedom could be won legally.

The life and trial of Mary Dyer show how dangerous it was to have different religious beliefs. Dyer was born around the early 1600s in Somersetshire, England.14 In the summer of 1635, Dyer and her husband set sail for Boston where they settled into Puritan life. They arrived in Boston as the Puritans were beginning to divide. Dyer became good friends with Hutchinson and attended Hutchinson’s lectures frequently with her husband.15 This suggests that Dyer’s surroundings, including both people and location, likely had an impact on her religious ideas. Dyer moved back to England in 1652, where she lived for five years. During her time in England, she became a member of the Quakers, a religious group.16 The Quakers were a group that had different beliefs than the Puritans. They believed everyone was equal

8 History of American Women, “Elizabeth Key,” History of American Women, https://www.womenhistoryblog.com/2008/01/Key-key.html.

9 James Almeida and Steven J. Niven, “Elizabeth Key,” Enslaved. org, https://enslaved.org/fullStory/16-23-101311/.

10 “Elizabeth Key,” History of American Women.

11 “Elizabeth Key,” History of American Women.

12 Almeida and Niven, “Elizabeth Key,” Enslaved.org.

13 “Elizabeth Key,” History of American Women.

14 Encyclopedia Britannica, ed., “Mary Dyer,” Encyclopedia Britannica, last modified May 28, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/biography/ Dyer-Barrett-Dyer.

15 Douglas O. Linder, “Mary Dyer Trials,” Famous Trials, https:// famous-trials.com/dyer.

16 “Mary Dyer,” Encyclopedia Britannica.

and wouldn’t take government oaths.17 Dyer came back to the Colonies, arriving in New Haven in 1658, to protest inhumane punishment: three of Dyer’s friends had their ears cut off for being Quakers. She and a few other protesters were thrown in jail and, a few months later, were banished under an anti-Quaker law. When Dyer later returned to Boston from Newport to support her friends who were arrested for holding Quaker meetings, she was sent to jail for a third time.18 Dyer stuck with her beliefs, despite the dangers she knew came with them. In 1659, Dyer and others were called to the General Court where they were lectured and sentenced to their hanging.19 In October of 1659, Dyer, along with two others facing the same punishment, were walked to the gallows where there were many soldiers with guns, swords, pikes, and flags. After her two companions were hanged, she was reprieved and temporarily returned to her cell before being sent to Rhode Island. She went off to Shelter Island with her neighbors for a few months where she held more Quaker meetings. In late April of 1660, Dyer left for Boston where she was given a trial. In June of 1660, Dyer was, once again, sent to the gallows where she was hanged.20 This shows how strongly Dyer felt about her beliefs, returning to face the punishment of death to prove a point, and how strongly and passionately she felt about what religious rights should look like. In the years after Dyer’s trial, King Charles signed the Rhode Island Charter, which was the first document to give religious freedom.21 Dyer’s trial and life had a major lasting impact, starting the change that eventually gave people religious freedom in the colonies and, in the years to come, the United States.

The Salem witch trials resulted in the creation, and later termination, of a new court and new laws, reforming what trials looked like in Colonial America. The Witchcraft Act of 1604 deemed witchcraft a felony.22 Additionally, the punishment for being a witch, which was defined as consulting with a spirit, is death.23 The Court of Oyer and Terminer was set up by the new governor, William Phips, to hear the cases of those accused of witchcraft.24 The trials had such an impact on the courtrooms that a whole new court had to be assembled specifically for the Salem witch trials. ‘Spectral evidence’ was the term used for claims from the victim that they had been attacked or witnessed witchcraft caused by the accused, who Satan allegedly used to perform his evil work. Many of the accused confessed to witchcraft and were spared the court’s punishment, believing that God would punish them. Those who didn’t admit to witchcraft were forced to become martyrs to the court’s idea of justice. Many community members didn’t say anything to object to these events because they feared being punished or accused of witchcraft.25 This had a major impact: the Salem witch trials resulted in the death of twenty people.26 Those affected were so terrified of being found guilty that they would give a false confession and then live most of the rest of their lives in fear of God’s punishment. The trials made citizens so scared that they didn’t dare to object to

17 Linder, “Mary Dyer,” Famous Trials.

18 Linder, “Mary Dyer,” Famous Trials.

19 Linder, “Mary Dyer,” Famous Trials.

20 Linder, “Mary Dyer,” Famous Trials.

21 Linder, “Mary Dyer,” Famous Trials.

22 New England Law, “The True Legal Horror Story of the Salem Witch Trials,” New England Law Boston, https://www.nesl.edu/blog/detail/a-true-legal-horror-story-the-laws-leading-to-the-salem-witch-trials#:~:text=Without%20specific%20colony%20laws%2C%20the,form%20of%20 an%20unwilling%20person.

23 General Laws and Liberties of the Massachusetts Colony, image, 2023, https://americanhistory.abc-clio.com/Search/Display/293243.

24 Key Frost-Knappman, “Salem Witch Trials,” American History, last modified 2023, https://americanhistory.abc-clio.com/Search/Display/252793.

25 Wallenfeldt, “Salem Witch,” Encyclopedia Britannica.

26 Sarah Gilman, The Salem Witch Trials (n.p.: Enslow Publishing, 2017), 32.

these unjust rulings and the often made-up spectral evidence. When accusations of witchcraft reached Governor Phipps’ wife, he ended the Court of Oyer and Terminer, instead establishing a Superior Court of Judicature, which didn’t permit spectral evidence. In the following two months, only three of the 56 accused were found guilty; all were pardoned by Phipps and the trials ended around May 1693.27 The General Court, in 1702, officially announced that the trials weren’t lawful.28 The trials needed spectral evidence for people to be proven guilty, as there was very little other concrete evidence. The accusations were formed off of so little that, when spectral evidence was taken away, it was very hard to prove that anyone was a witch. The fact that spectral evidence was no longer allowed after the Salem witch trials and that the trials were later ruled unlawful shows how greatly the trials affected the development of law.