16 minute read

Screen Queen

Criterion films celebrate diversity in all its forms

By Chris Azzopardi

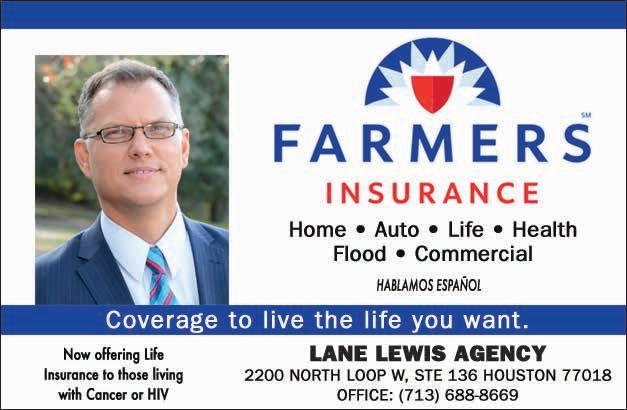

Advertisement

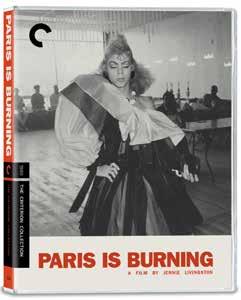

Paris Is Burning In Paris Is Burning, a strut is a defiant act, an exertion of suppressed power. In the mid-to-late 1980s, when the landmark documentary was filmed, these moves couldn’t be showcased just anywhere. Today the same is true, as the call to end violence against trans people and to confront transphobia persists. Given the number of trans people killed since the doc was released (and the surge of trans murders currently making headlines), that call seems, still, to fall on deaf ears. And so white, queer, nontrans director Jennie Livingston’s 1990 film remains fiercely important, as much a time capsule as a reflection on how much progress has been made (and has yet to be made), its haunting relevance resonating yet again during our modern LGBTQ and Black Lives Matter movements. At the time of its release, Livingston’s doc illuminated issues of transphobia, racism, AIDS and poverty through intimate, everyday depictions of legendary voguers, drag queens and trans women, including Pepper LaBeija, Dorian Corey and Venus Xtravaganza, as they found both refuge from the oppressive outside world and a unifying sense of community within the drag-ball and voguing; it was the doc that opened the door for TV’s groundbreaking transcentric show Pose and Netflix’s new doc on trans depiction in media, Disclosure, which acknowledges the classic doc’s historical significance while also critiquing it for being exploitative of a seriously marginalized community. The Criterion Collection’s digital restoration of the film features an episode of The Joan Rivers Show from 1991, with Livingston and ball community members, who teach Rivers queer slang; a new sit-down with Livingston, Sol Pendavis, Freddie Pendavis and filmmaker Thomas Allen Harris; and over an hour of never-before-seen footage. “Now more than ever, the call for realness, that reverberating standard of ball excellence, is required,” writes Black LGBTQ activist and filmmaker Michelle Parkerson in an essay in the 38-page liner notes of the Criterion release, which also includes a 1991 review by the late, Black gay poet and activist Essex Hemphill. In 2020, the film’s urgency can be heard loud and clear: our greatest act of defiance, it reminds us, is living

scene. Paris Is Burning introduced shade authentically, for the whole world to see.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire Forbidden love flourishes in the quietest of corners, outside of view, beyond the patriarchal pressures of conformant. So it goes in writer-director Céline Sciamma’s achingly beautiful, queerfeminist love story Portrait of a Lady on Fire, where fire, often in a literal sense (there is lots of actual fire), burns fiercely and freely between two women, one an enamored painter, the other her reluctant subject. Sciamma sets her story in the late 18th century, during the dawn of the Romantic era. A young painter, Marianne, played by French actress Noémie Merlant, arrives on a remote island off the coast of France to paint Heloise, played by French actress Adèle Haenel. The portrait is to be her wedding portrait, but Heloise doesn’t want to marry the man she is about to wed, so she refuses to pose. As Marianne’s relationship with Heloise blossoms, it’s clear she will have a better chance at capturing Heloise than the previous portrait artist, who left without accomplishing the task of painting Heloise. But Marianne is different, patient. She draws Heloise from memory in secret until she establishes her trust; she speaks to her in a way no one likely ever has, her attraction expressed fervidly through sometimes nothing more than small, stolen moments when she fixes her enraptured eyes on Heloise. Aesthetically, the film is a ravishing work of art all its own, a kind of visual poetry that cinematographer Claire Mathon captures to breathtaking effect. In stunning 4K, Criterion emphasizes the sumptuous beauty given in each scene. Beyond the film itself, the Bluray includes a new conversation with Sciamma and film critic Dana Stevens, new interviews with Haenel and Merlant, and an interview with Mathon.

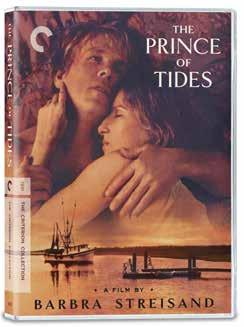

All About My Mother In the 1999 Spanish drama All About My Mother, the celebrated gay film visionary Pedro Almodóvar’s reverence for women movingly permeates every vibrant frame of his loving ode to sisterhood. Self-assembled family units are, of course, a dynamic that is an-oft necessary way of life for members of the LGBTQ community, which All About My Mother honors through the character of Agrado (played by Spanish actress Antonia San Juan), an early figure of transgender representation, and the way in which Almodóvar matter-offactly folds her into a blended family of characteristically diverse women. Those women include Sister Rosa (Penélope Cruz), an HIV-positive nun; Huma Rojo (Marisa Paredes), an iconic actress; and the film’s griefstricken protagonist, Manuela (Cecilia Roth), whose determination to stay connected to her teenage son after his sudden death leads her to discover the magic of chosen family and the healing bonds those relationships engender. In a 1999 written tribute republished in Criterion’s digital restoration of the film, Almodóvar reflects on whimsical distortions of truth for the screen, and a perspective his mother shared with him as a child that became the impetus for All About My Mother, one that is hard to argue with: “how reality needs fiction in order to be complete, more pleasant, more livable.” Elsewhere, Criterion’s Blu-ray release includes a 52-minute documentary from 2012 on the making of the film, a TV program featuring Almodóvar and his mother, and a post-screening Q&A from 2019. The Prince of Tides Barbra Streisand has garnered far less attention for her work behind the camera than in front of it, even though she was instrumental in dismantling the status quo of male-dominated directors. And so, her film The Prince of Tides rightfully deserves Criterion treatment, with all the bells and whistles presented here, including a stunning 4K transfer and lots of Babs. She is featured in several interviews, and supplies a thoughtful audio commentary, recorded in 1991 and updated in 2019. There’s audition and rehearsal footage, behind-the-scenes footage and an alternate ending that features a song that Streisand wrote for the film called “Places That Belong to You,” cut from the movie so as not to distract from the film’s central character study. Released in 1992, The Prince of Tides was Streisand’s second feature as a director, after her 1983 telling of Yentl. So emotionally invested in Pat Conroy’s novel of the same name years before its release, Streisand’s cinematic take on the story, which she also starred in and produced, scored seven Oscar nominations and traverses genre borders, from schmaltzy romance to family drama and, during the film’s most horrific reveal, a shocking

thriller. The film features the multihyphenate living legend as Dr. Susan Lowenstein, a psychiatrist who unearths one family’s buried trauma. She does so through regular meetings with Tom Wingo (Nick Nolte) after his sister, Savannah, tries suicide. Of note: George Carlin as Eddie Detreville, Savannah’s trusted gay neighbor, and Streisand’s gay son Jason Gould, who plays her son in the film. Moving through, and past, trauma is the film’s crux, until it makes a full-on soap-opera leap and centers the soppy love-conquers-all romance between Streisand and Nolte, undermining the drama’s stronger, more complex themes. What’s admirable, though, is how, nearly three decades ago, Streisand shined a light on the potential danger of toxic masculinity and nurtured a project that encouraged men to embrace sensitivity and vulnerability. e

Chris Azzopardi is the editor of Q Syndicate, the LGBTQ wire service. His work has also appeared in The New York Times, Vanity Fair, GQ and Billboard. Reach him via Twitter @chrisazzopardi.

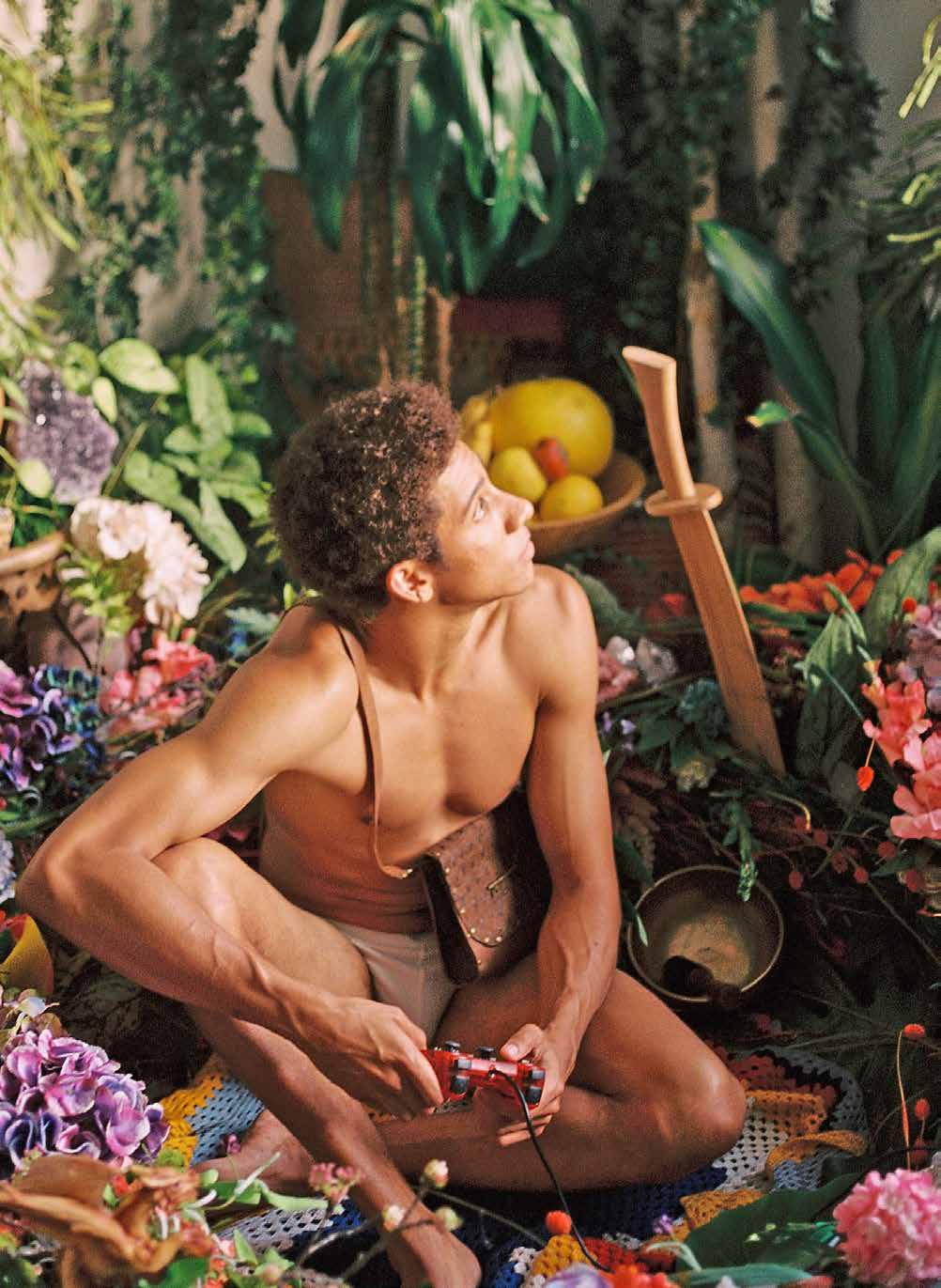

KEIYNAN LONSDALE

His black queerness , front and center

‘Love, Simon’ star Keiynan Lonsdale talks defiant solo album, social justice uprising and embracing his Black queer identity

e By Chris Azzopardi

ONCE KEIYNAN LONSDALE MADE no apologies for who he is, the music followed suit. The star of the CW’s The Flash and 2018’s gay teen comedy Love, Simon celebrates his Black queer identity on his 14-track anthemic solo debut Rainbow Boy. Dance-pop song “Gay Street Fighter” is an audacious strut of a rally cry, proclaiming that even God is gay. And with a shout out to “my nonbinary bitches,” “White Noise” and its buoyant groove lifts the stories of Black people that have fallen through the cracks.

Lonsdale’s album comes at the same time as Love, Victor, the Love, Simon spin-off on Hulu. In the series, the 28-year-old Aussie star reprises his role as quiet high-schooler Bram and becomes instrumental in Victor’s journey to authenticity.

When I recently connected with Lonsdale during a Zoom call, he was riding out the last two days of his mandatory 14-day quarantine in a hotel in Australia. At one point, the phone rang. And then it rang again. “Don’t mind me,” Lonsdale said, laughing. “I’m in the Australian quarantine right now, and so, actually, they call and check on you each day.”

In quarantine, Lonsdale has been able to “take stock of the album release, the state of the world…” He laughs again. “And the state of myself.”

Were you feeling as defiant as the music on this album when you recorded it, or was it a personal manifestation?

Yeah, I was 100 percent feeling just as defiant. The songs were written, for the most part, pretty easily. There was so much that was ready to be expressed. And I think the momentum kept building, because I hadn’t felt that empowered to be able to write and make music that was so unapologetic. It felt really, really ripe.

When did you feel you could be unabashedly yourself in your music?

There was definitely one moment; it was three years exactly before I released it, where I had this realization that the best way for me to create would be to hold absolutely nothing back. I realized I was in control of the songs that I would write, and it would be a matter of what the writing led with, or staying in this sort of fear mindset that I had my whole life. And for good reason.

But it felt kind of like a spell was broken, and I was like, “I can say this shit, I can sing this shit.” (Laughs) In fact, it’s what sparked me to realize that I could have my own unique voice. Before that I would say that I spent a lot of time trying to be like others, but always wanting to have the gall to be able to be my own (person). But I didn’t know what that meant. So it

So then being able to mentor a younger gay person on Love, Victor and remind him that there’s no one way to be LGBTQ, what did that feel like for you?

It was great to be able to play a role that could share that knowledge, because it’s something that I think each of us have needed to hear at one time: that you are still the one that gets to define who you are. There is no one way, and as much as we like to paint people with the same brush, it’s just not how it works. So I think it sends an important message. I’m glad that’s the route they went with with the (lead) character.

Going back to the fear you said you felt when you were younger, before you came out: How much of that had to do with you being a Black queer person?

Yeah, it had a lot to do with that. I didn’t hear and I still don’t hear … (there’s) a lack of music that proclaims same-sex love. What’s ultimately needed is that it’s normalized; that hearing a guy sing about a guy or singing about a girl, they can become one in the same and not something that is conflicting or jarring or uncomfortable, or something that people have to avoid. Photographer Mark Clennon, who has been sharing images of the Black Lives Matter protests and demonstrations across New York City, described sharing Black stories as “whimsical defiance” in a recent interview with Interview magazine. For you, what does it feel like to be sharing your perspective and story as a Black queer person during our current racial justice movement?

It’s both empowering and exhausting. I think a lot of Black people would likely feel this way too, because it’s a story we’ve lived with our entire lives. For a lot of us, we’ve expressed it for a while. You know, I wrote a whole album about my experience, and I wrote the album, like, two years ago. So, it’s coming out now and it’s amazing on one hand that people are listening in a different way than they were before. That provides me with a lot of hope on some days. On other days you just want to live your life. You want to be able to live your life without having to explain it all the time. And so I think that’s where it’s important to have the balance of doing the fight and also knowing, How do you heal at the same time? Take care of yourself? So, yeah. It’s hard to describe.

I’m assuming the song “White Noise” was written a couple of years ago too. During the song, you sing, “All the white noise that we just don’t need, you better move over.” What kind of significance dotes the song take on now in the midst of this uprising?

It has reminded me of the necessity of it. I was of the mind where I felt like maybe this song was too on the nose, but then, clearly not. (Laughs) There are a lot of people who don’t understand the importance of this, and I wanted to approach that song with a level of joy and invitation, to be able to point out an issue, pretty clear as day, yet to say that there’s a way forward. I suppose everyone has a different way of how they share their message, and with that song I wanted to kind of teach – and with the album, in general – through song and dance.

You taking pride in your Black heritage on “Ancient One” is a good example of that.

One-hundred percent. Because I think the goal of life is to celebrate that we are here, and that we get to share this experience. It’s important to have reminders that there is a lot to this existence, and that it can be something that is full of rhythm and full of mystery and full of celebration. diversity, something many people thought Love, Simon lacked. What are your feelings on how the show and the movie handled representation?

I haven’t seen the show in its entirety yet, so I look forward to that. But that was definitely one thing I thought was exciting about this show. When anything is getting a spin-off, you get a little bit worried and you’re hoping that it’s done the right way. But I appreciated that it was taking a turn from the movie and moving forward, taking further steps.

In one way, I’m really proud of Love, Simon and how things were represented, but I’m not unaware of the fact that that was one step and that there are still many that need to be taken. As people also said, this is one specific telling of what it is for one kind of person to grow up gay in a fairly accepting environment, in a sort of privileged position. And those are conversations to be had. I’m glad that the movie was both celebrated yet also a topic of discussion of, “How do we keep going?”

When you accepted your MTV Movie award for “Best Kiss” for Love, Simon in 2018, what was it like to get on stage as an out queer person and in a dress?

It was super weird because I had come out a few weeks after we’d filmed (Love, Simon), so I was out for only 12 months by the time the movie was out. Then I was doing all these interviews and speeches; it was really strange because I only just came out. I was kind of very much in my own experience trying to figure a lot of stuff out.

But you seemed to have known what you were doing when you got on that stage in that dress. (Laughs) Yeah, well … I was just trying my best to listen to the spiritual aspect of it and that’s what allowed me the confidence to wear what I wanted.

How did you feel up there?

I felt amazing. I was really nervous. I didn’t know what I was going to say until I started walking up. It’s a surreal kind of experience. But I was over the moon, to be honest. It felt like a dream. And I felt really supported in that moment. And

Love, Victor has been getting attention for its

yeah, it was quite magical. I felt magical.

Did you see the crowd reactions? They were so into your speech.

I definitely heard them. It was really exhilarating.

I see how you affect a lot of LGBTQ youth, and to that end, I wondered what you think being out and playing Kid Flash has meant to both LGBTQ and people-of-color communities?

It’s meant a lot of things. Because at first it was met with a lot of celebration, but I was also met with thousands of racist comments online the day that it was announced. Same thing when I came out. To be met with such celebration but then also the opposite, it’s a funny juxtaposition. But I am proud. I’m happy that Kid Flash is a superhero and the message I know that a lot of kids have been getting is: They’ve got to watch me as a Black man play a superhero, and then they compare it with the fact that I’m an out queer Black man who plays a superhero. We weren’t taught you could do that back in the day. And so if that empowers kids to know they can be limitless, then that’s the best thing ever. e

As editor of Q Syndicate, the LGBTQ wire service, Chris Azzopardi has interviewed a multitude of superstars, including Cher, Meryl Streep, Mariah Carey and Beyoncé. His work has also appeared in The New York Times, Vanity Fair, GQ and Billboard. Reach him via Twitter @chrisazzopardi.