6 minute read

COMMUNITY-BASED PLANNING PROCESS FOR THE IMPLEMENTATION OF SUSTAINABLE NEIGHBOURHOODS

14

Even though some traditional steps of the rational planning process might be followed to successfully implement a neighbourhood development project (such as establishing objectives, determining alternatives, and assessing viability) (see Figure 3), the fact that community-based planning is based on strong democratic dynamics restricts the possibility of implementing a traditional autocratic approach to planning (Fainstein & Fainstein, 1972; Chapman, 1996; Peterman, 2000).

Advertisement

Therefore, in order to allow public participation in every step of the way, community-driven neighbourhood planning processes should be collaborative, open and transparent (Peterman, 2000), or in other words inclusive and enabling (Chapman ed., 1996).

Figure 3 - Rational Planning Process

However, physical and social particularities of community-based developments have made it difficult to define a general planning model for their implementation. Nevertheless, identifiable concepts appear to be common among authors and publications dealing with local development issues.

15

To begin with, most authors recognised that in order to implement effective grassroots developments, projects should be driven by local civic associations (Blakely & Bowman, 1985; Kumaran, Hyma & Wood, 2004; Pierson, 2008). These associations could include community organisations, community development corporations, or advocacy planners working with local communities (Peterman, 2000), and would be recognised as the main actors in the planning process.

Once the promoters of the process are identified, theory presents the definition of ‘shared objectives’ as one of the main requirements of a community-based planning process (Local Agenda 21). As Fainstein & Fainstein declared:

“the definition of a common interest for the whole community is “the definition of a common interest for the whole community is one of one of the major theoretical obstacles on the democratic planning the major theoretical obstacles on the democratic planning process” process”(Fainstein & Fainstein, 1972, p.196). (Fainstein & Fainstein, 1972, p.196).

Therefore, on this first stage the celebration of community meetings supported by the role of planners are basic to define and legitimise core objectives for future developments (Fainstein & Fainstein, 1972; Chapman, 1996).

These community meetings would also enable advancement of ‘capacity building’ processes for community members (Kumaran, Hyma & Wood, 2004).

“Capacity building contributes to the growth of assets such as “Capacity building contributes to the growth of assets such as ‘human ‘human capital’, which includes the skills, knowledge and abilities capital’, which includes the skills, knowledge and abilities of those of those who live in the area. It also builds ‘social capital’, which who live in the area. It also builds ‘social capital’, which includes the includes the social networks, the sense of trust and the willingness social networks, the sense of trust and the willingness to volunteer” (Pierson, 2008, p.27) to volunteer” (Pierson, 2008, p.27)

Capacity building is particularly important because it involves the generation of knowledge and technical skills that allow local communities to communicate their interests effectively (Chapman, 1996).

16

‘Collaboration’ and ‘developing partnerships’ are also popular concepts between local development theories, related with both top-down (Local Agenda 21, Chapman, 1996; Kumaran, Hyma & Wood, 2004) and bottom-up approaches (Morris & Hess, 1975; Blakely & Bowman, 1985; Pierson, 2008).

William Peterman had declared that community leaders should William Peterman had declared that community leaders should build and build and maintain political, technical, legal and financial linkages maintain political, technical, legal and financial linkages with people and with people and institutions outside their own community, as well institutions outside their own community, as well as coalitions with other as coalitions with other communities and organisations (Peterman, communities and organisations (Peterman, 2000). 2000).

On this matter, connections with individual investors, organisational and institutional aids consistent with community objectives, charitable organisations, government organisations and local and regional community banks would facilitate the acquirement of monetary resources (OECD, 1998). Whilst partnerships related with technical expertise could also be useful in training, preparing and supporting collective projects. By working in ‘partnerships’ and based on a ’creative tension‘ between community and governmental agencies (Peterman, 2000), the concept of ‘governance’ also strengthens (Pierson, 2008).

Additionally, ideas such as ‘building trust’ and relying on ‘volunteer work’ are extensively mention on literature reviews. In theory, most of these concepts appear related with the idea of a ‘Community Action Plan’ as a way of:

“enabling communities to identify issues and priorities and to de“enabling communities to identify issues and priorities and to develop and velop and implement solutions to their problems through participaimplement solutions to their problems through participation rather than tion rather than providing externally driven programs and projects” providing externally driven programs and projects” (Kumaran, Hyma & Wood, (Kumaran, Hyma & Wood, 2004; p. 34). 2004; p. 34).

Community Action Plans are presented in relation to local economic development processes (Blakely & Bowman, 1985; OCDE, 1998), as well as for the sustainable improvement of existing neighbourhoods (Kumaran, Hyma & Wood, 2004). Therefore, it is possible to consider them as basic components of a community-based planning process.

17

COMMUNITY-BASED PLANNING MODEL

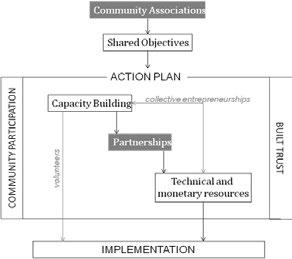

18 The concepts presented in literature and discussed above has been considered as the basic input to develop a Community-Based Planning Model proposal (Figure 4) to be used in the analysis

ADVOCACY PLANNERS

of the selected case studies. The model presented in Figure 4 identifies observations related with the idea that community developments should arise from grassroots organisations (Peterman, 2000). It also considers the legitimacy of shared objectives of a community (Fainstein & Fainstein, 1972; Chapman, 1996), as well as the development of an Action Plan, as the basic steps of the planning course (Blakely & Bowman, 1985; OCDE, 1998; Kumaran, Hyma & Wood, 2004).

In the literature, the role of advocacy planners also appears as an important factor supporting the planning process from the beginning. However, this role should not be of paternalistic nature, rather it should focus on the connection between community movements and governmental institutions (Fainstein & Fainstein, 1972).

The design and implementation of Action Plans should be based on inclusiveness and dynamic processes, including capacity building for the community and establishment of partnerships with public and private stakeholders (OCDE, 1998; Peterman, 2000; Kumaran, Hyma & Wood, 2004; Pierson, 2008). As stated above, capacity building is a basic to develop human and social capital, enabling the generation of technical knowledge and volunteer support for the development process (Pierson, 2008), as well as providing opportunities for the rise of collective entrepreneurships as an internal way of generating economic resources (OCDE, 1998). Collaboration and partnerships provide knowledge that strengthens social capacity, and monetary resources that are fundamental for the implementation of the development (OCDE, 1998). Community participation and trust building between local actors and community members are conditions presented in every step of the way (Chapman, 1996; Peterman, 2000; Kumaran, Hyma & Wood, 2004; Pierson, 2008).

19

ADVOCACY PLANNERS 20 Since this planning process is contextualised at the local scale, its capacity to generate outcomes will be directly related with its success (Mansuri, 2004). The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OCDE) in their ‘Territorial Development’ publication suggest that a set of required outcomes legitimises community intentions, thus facilitating access to monetary resources for the implementation of projects. These outcomes include: ‘Community Statues’ and ‘Economic Assessment’, as a way to “make social performance compatible with economic efficiency” (OCDE, 1998, p.67). Eventually the need to develop a technical project should also be fundamental to build the idea. These three outcomes have been included in the Community-based Planning

Process Model for further analysis (see Figure 5).

As a final consideration, it is important to recognise a general agreement between all the consulted sources, concluding that for the implementation of community-based development to be successful, it is necessary to switch from the governmental regulatory mode to a more democratic one base on ‘enabling and facilitating’ community entrepreneurships.

21