3 minute read

Medical and Surgical Management of Ocular Inflammatory Disease

BY AKBAR SHAKOOR, MD

Ocular inflammatory disease, including uveitis, scleritis, and orbital inflammatory disease, can be acute or chronic, infectious, non-infectious, or present as a masquerade syndrome. Therefore, its management is manifold, and a comprehensive medical and ocular history and targeted laboratory workup are critical to appropriate therapy.

ASSESSMENTS

First, it is important to consider and assess for infectious disease to administer the correct antimicrobial therapy if an infectious process is suspected. Physicians should only consider steroids and other immunomodulatory therapy once ruling out infectious processes.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

In the medical management of non-infectious uveitis, corticosteroids play a major role, either by themselves in acute disease, as a bridging therapy in conjunction with corticosteroid-sparing immunomodulatory therapy (IMT), or in patients on systemic medications. They may be administered topically, regionally (periocular or intravitreal), orally, or intravenously depending on the anatomic location and severity of the uveitis.

Avoid long-term exposure to corticosteroids, which can cause a litany of ocular and systemic complications. Topical and locally administered corticosteroids may produce cataracts and induce glaucoma. Systemic administration can cause many side effects, including ocular complications, hypertension, weight gain, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, myopathy, osteoporosis, and avascular necrosis of the hip.

To manage chronic ocular inflammatory disease, “corticosteroid-sparing” IMT is often used to limit these complications. Immunomodulatory medications may be grouped into conventional agents, which include:

• Antimetabolites (methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, and azathioprine).

• T-cell inhibitors (cyclosporine and tacrolimus).

• Cytotoxic medications (cyclophosphamide and chlorambucil).

• Newly emerging biologic response modifiers, including the anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibodies (infliximab and adalimumab).

• Monoclonal antibodies targeting specific proinflammatory cytokines such as rituximab (anti-CD20) and tocilizumab (anti-IL-6).

Sustained-release steroid implants are another option to provide prolonged anti-inflammatory therapy and limit systemic corticosteroid exposure. Clinicians may anchor these implants in two ways:

• Via sutures to the pars plana, as with the fluocinolone acetonide implant (Retisert, Bausch + Lomb).

• Injected intravitreally, such as the intravitreal dexamethasone implant (Ozurdex, Allergan) and the fluocinolone acetonide intravitreal implant (Yutiq, EyePoint Pharmaceuticals), shown to be effective in the management of posterior uveitis for up to one to three years after injection.

Although effective, sustained-release implants carry a high risk of corticosteroid-induced cataract formation and glaucoma requiring medical and/or incisional surgery in a high percentage of patients.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgical approaches to the management of uveitis may be therapeutic and diagnostic. Multiple structural complications requiring surgical management occur in uveitis cases, including cataract formation, glaucoma, vitreous hemorrhage and opacity, and epiretinal membrane formation.

Surgery should be performed with caution, although with appropriate perioperative planning, anterior and posterior segment surgery can be performed safely and effectively.

Therapeutic vitrectomy may be performed with cataract surgery or by itself to clear media opacity, in conjunction with epiretinal membrane peeling, or to address retinal detachment, peripheral retinal non-perfusion, and hypotony.

Pars plana vitrectomy may help manage intermediate uveitis by reducing antigen and cytokine load in the eye. In conjunction with cataract surgery, pars plana vitrectomy may reduce the postoperative incidence of posterior capsular opacity, cyclitic membranes, hypotony, and cystoid macular edema. Certainly, in our cohort of patients, a combined surgical approach appeared to be safe and effective in visual rehabilitation in patients with uveitic cataracts. The majority of eyes (64%) achieved vision of 20/40 or better, and 21% achieved complete drug-free remission of inflammatory disease at the one-year follow-up.

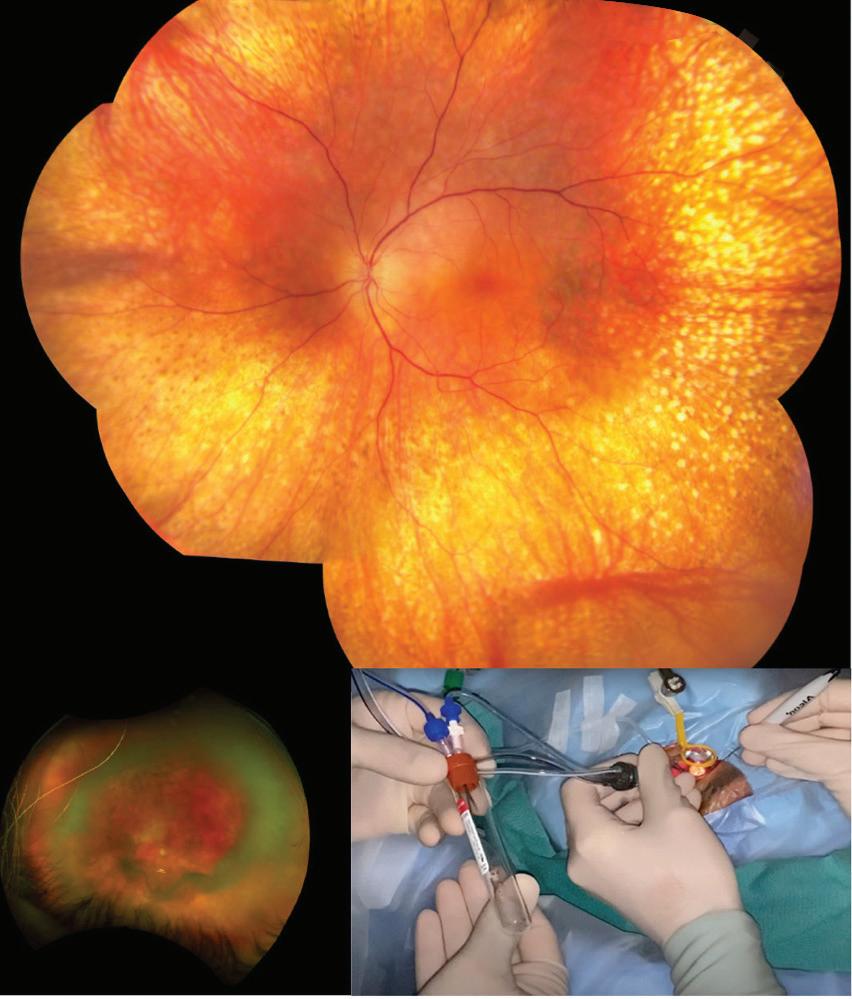

Diagnostic vitrectomy and chorioretinal biopsy may be critical in diagnosing infectious uveitis and neoplastic disease, which may masquerade as ocular inflammatory disease that presents atypically or responds unexpectedly to therapy.

A large volume of undiluted vitreous may be obtained using air infusion into a simple vitreous trap system (See Figure 1 below) for a variety of assays. Chorioretinal or sub-retinal aspiration biopsies must be appropriately processed and fixed prior to histopathologic evaluation.

In summary, ocular inflammatory disease treatment requires a multimodal approach individualized to each patient following careful disease evaluation and appropriate exclusion of infectious and neoplastic processes.

Dr. Shakoor specializes in medical and surgical diseases of the retina and vitreous, and the diagnosis and treatment of uveitis and other infectious and inflammatory diseases of the eye. He is director of the Uveitis Fellowship Program.

Figure 1: A 71-year-old woman received a referral for persistent vitritis after cataract surgery. A surgeon performed a diagnostic vitrectomy, which yielded a large sample of undiluted vitreous. Cytology, flow cytometry, and genetic studies revealed large B-cell lymphoma.