7 minute read

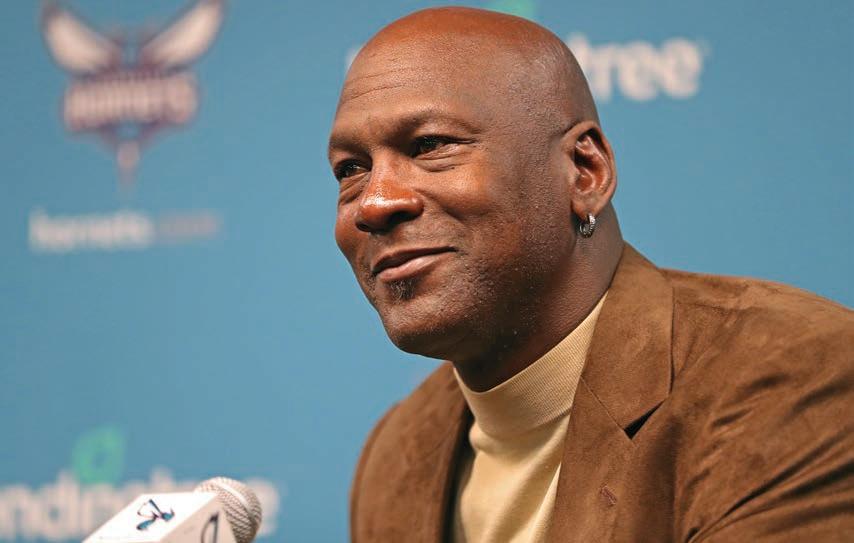

Michael Jordan

CHARLOTTEANS OF THE YEAR MICHAEL JORDAN

In a turbulent year of protests and a pandemic, he reminded us what greatness looks like

BY TAYLOR BOWLER

THE YEAR IS 1992. I live in a suburb of Chicago where kids ride bikes with skinned knees and little parental supervision. A visit to the McDonald’s at the top of the Sears Tower is a rite of passage for every kindergartner, and the whole neighborhood is abuzz when someone’s mom gets tickets to The Oprah Winfrey Show. Every third-grader I know can sing the “Be Like Mike” jingle by heart, and not just because we like orange Gatorade. Mike’s our hometown hero with the famous tongue wag who wears the sneakers that make you y.

Michael Jordan turned ’90s kids like me into basketball fans. But as so many of us cheered for His Airness, others wondered why he seemed to shy away from what they rightly considered far more important than basketball or business success: matters of social justice. This year, Jordan nally entered that arena, and at 57, three decades a er his peak as an athlete, reminded us why he’s still the Greatest of All Time. WHEN THE LAST DANCE AIRED on ESPN this year, millions tuned in every Sunday for ve weeks, and not just because there weren’t any live sports on TV. The Bulls’ run of six titles over eight seasons remains one of the greatest feats in professional sports, and for those of us who grew up cheering for them, the show allowed us to go back in time.

When the NBA rst approached him about a lm crew following the Bulls during the 1997-98 season, Jordan says then-Commissioner David Stern told him if nothing came of the footage, at least he’d have some great home movies to show his kids. “It turned out to be true,” he tells me via email, “only the rest of the world got to see those home movies, too.” Jordan’s three older kids, Je rey, Marcus, and Jasmine, got to see a new side of their father. “They knew me as Dad, with the perks of free sneakers and Bulls’ tickets and some sense that their lives were di erent than some of their friends’ lives. All these years later, they had great reactions to things they might have remembered but not fully understood.”

Jordan’s competitiveness is legendary, and his rivalry with the Detroit Pistons’ Isiah Thomas, a Chicago native, was erce—that much we knew. But we didn’t know all the details of his relationships with teammates Scottie Pippen, Dennis Rodman, and Steve Kerr. The stories weren’t all attering. MJ mocks general manager Jerry Krause’s height and punches Kerr in practice. But the documentary makes us consider whether that was part of Jordan’s greatness, too—his willingness to command respect at the cost of being liked.

And that underscores one of the biggest contradictions of Jordan’s life, one that The Last Dance doesn’t hesitate to address. As the most prominent Black athlete of his era—maybe of all time— Jordan steered away from politics and advocacy for Black Americans during

and a er his athletic career, in contrast to forebears like Muhammad Ali, Jim Brown, and Arthur Ashe.

Most famously, Jordan declined to publicly support Harvey Gantt, Charlotte’s rst Black mayor, during his 1990 U.S. Senate race against Jesse Helms in Jordan’s home state. Jordan was 27 then, and he maintained a depoliticized image that helped him land endorsements with Nike, Gatorade, McDonald’s, and Hanes. Asked about it then, he responded with a one-liner—“Republicans buy sneakers, too”—that fed a popular perception that would dog him for nearly 30 years: that he cared only about winning championships, gambling, and his business brand. Even President Obama admits in the docuseries that he wanted Jordan to publicly endorse Gantt and push harder on issues of social justice.

“I never thought of myself as an activist,” he says in The Last Dance. “I thought of myself as a basketball player.”

That began to change this decade, as highly publicized police killings of Black people jump-started Black Lives Matter. In 2016, Jordan wrote a personal essay for The Undefeated that referred to his father’s 1993 murder by a pair of armed robbers, then pledged $1 million to both the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund and the Institute for Community-Police Relations.

Then, in May, came the event that galvanized Jordan as it did so many others: George Floyd’s killing. “I am deeply saddened, truly pained and plain angry,” he wrote in a statement he shared on the Jordan Brand’s social media accounts. “I stand with those who are calling out the ingrained racism and violence toward people of color in our country.” It was by far the most pointed and openly political public statement Jordan had ever made. The fact that he voiced it made headlines around the world.

“Frankly, I just had enough,” he tells me. “Despite all that I have in this world, I am not immune from racism. My family is not immune from racism. I have a voice, a platform, and the means to try to e ect change on a big scale.”

JORDAN’S NAME WILL ALWAYS BE synonymous with Chicago, but we claim a big piece of him in Charlotte, too. In 2010, he became majority owner of the Charlotte Hornets—and the only Black majority owner in U.S. pro sports. “Even when I lived in Chicago, North Carolina never stopped being home for me,” he says. “It was truly a dream come true to become the majority owner of an NBA team, and for it to be the Hornets made it even more special.” He shared his statement a er George Floyd’s death on the Hornets’ Twitter account, too.

He owns a lakefront home in Cornelius and a penthouse condo within walking distance of Spectrum Center. But a Jordan sighting in Charlotte is rare. He remains notoriously private, with no social media presence and few public interviews. He’s so private, in fact, that he wouldn’t allow The Last Dance crew to lm at his own house—those interviews were actually lmed at three di erent homes near his residence in Jupiter, Florida.

If you look closely, though, you’ll see the trail he leaves across the city. His $7.2 million donation funded the Novant Health Michael Jordan Family Medical Clinic on Freedom Drive. By the second half of 2020, cars lined up outside its drive-up clinic because patients didn’t need an appointment or a primary care provider to get a COVID-19 test. In September, Novant opened a second clinic on Statesville Avenue. He also donated proceeds from The Last Dance to Friends of the Children, a national nonpro t with a Charlotte chapter that provides mentors to at-risk youth.

Along with Jordan Brand, he’s pledged $100 million over the next 10 years to organizations dedicated to racial equality and focused his rst three rounds of grants on fair voting. He pushed to have Spectrum Center used as a polling place, which the Mecklenburg County Board of Elections approved, and says he’ll continue to work with organizations to undo “centuries’ worth of damage.”

JORDAN’S NEXT MOVE involves another sport with deep ties to Charlotte: NASCAR. He’ll join longtime Cup driver Denny Hamlin to form a single-car team for the 2021 season with Bubba Wallace as the team’s driver. The move symbolizes more than a historic deal for NASCAR. With the sport’s only fulltime Black driver behind the wheel, it’s another step toward diversity—and a mark of the NBA legend changing the culture of a sport.

Since he retired from basketball for the third and nal time in 2003, he’s had little success as an NBA owner. His public image as the ultimate winner eroded with the years; a generation of kids knows him from the “Crying Jordan” meme, which he alluded to this year at the memorial service for Kobe Bryant, an athlete many viewed as his successor. Still, he remains the highest-paid athlete of all time, and he’s been good to his home state. For years a er his basketball career ended, his greatness didn’t shout. It whispered—until the time nally came for it to raise its voice.

“I think ‘greatness’ comes with a vision for success, commitment to putting in the time and a lot of hard work, and dedication to whatever it is you’re doing, whether it’s your job, a hobby or something else,” he says. “You can’t be afraid to fail; that’s how you learn.”

Greatness refuses to be limited or controlled by fear. It outlasts bad days marked by protests and pandemic. Greatness is an athlete who can take you back to a time when sneakers made you y, when Donald Trump was just that guy who made a cameo in Home Alone 2: Lost in New York, when pinky promises were forever.

And this ’90s kid will never forget it.

TAYLOR BOWLER is lifestyle editor of this magazine.