12 minute read

A RECREATIONIST’S DREAM

Charlotte :

DR E A M ARECREATIONIST ’S

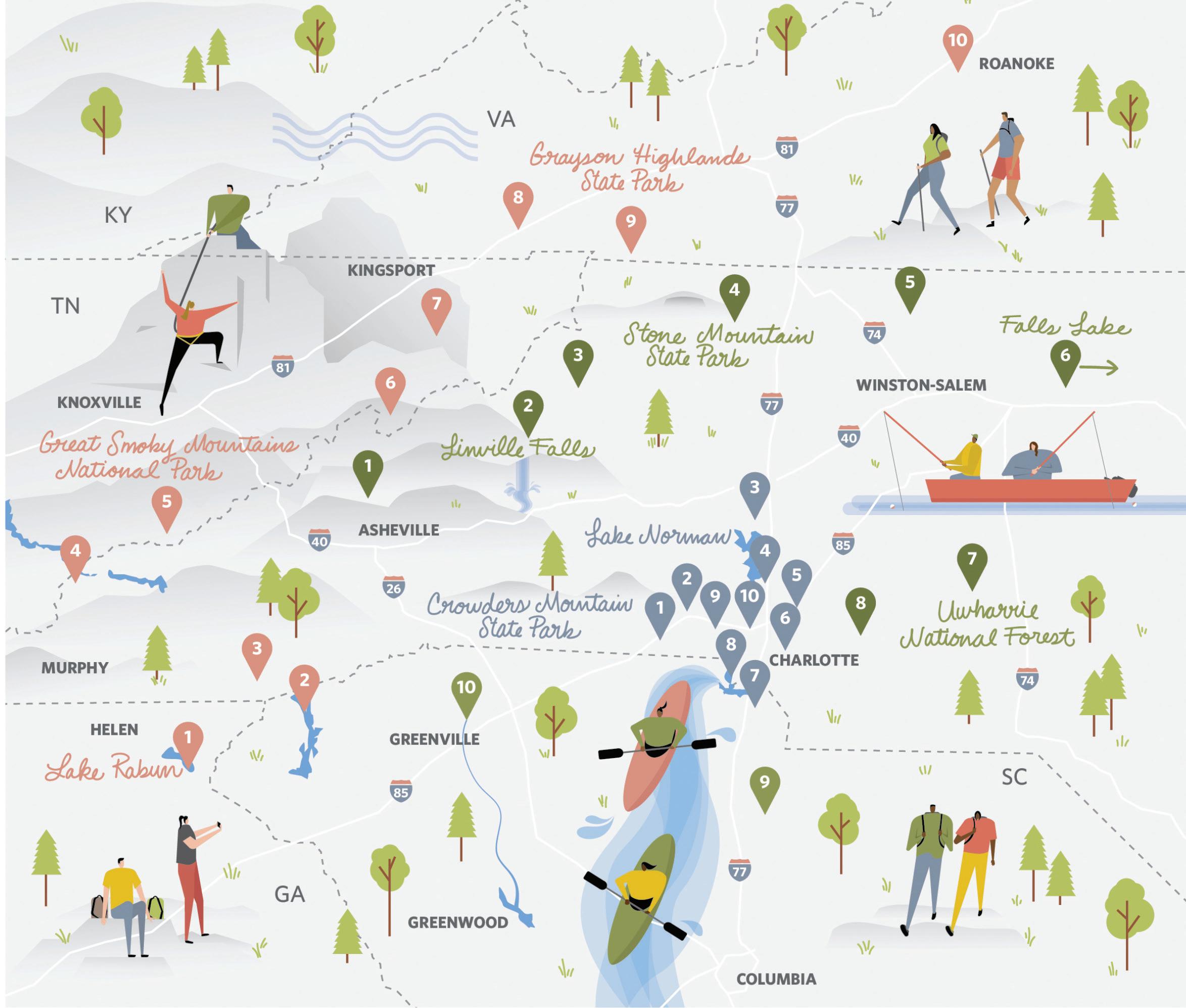

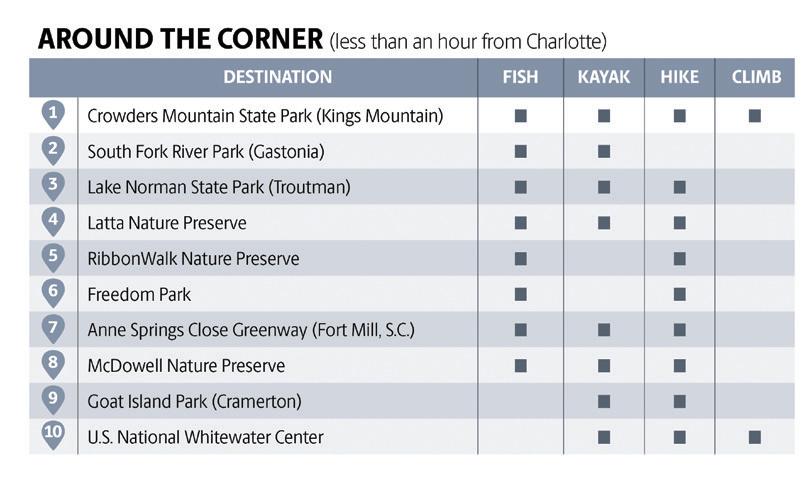

From the environs of the 34-mile long Lake Norman to the panoramic views atop Crowder’s Mountain to the parks found within the city proper, the Charlotte area is perfect for the nature enthusiast. Join us for a trek.

30 OUTDOOR ESCAPES IN AND NEAR CHARLOTTE

BY CHARLOTTE MAGAZINE STAFF

Charlotte urbanizes more each day, yet the skyline’s shadow still falls on pockets of nature. A true escape isn’t far away, either: Lakes, state and national parks and natural wonders encircle the city. Here, we’ve compiled 30 destinations ripe for exploration and divided them into three groups: Around the Corner, Day Trip and Weekender. Use the key for distance from Charlotte and the activities there.

FISHING

Laws change state to state, so we’re focusing on North Carolina. The N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission sells short-term (10-day), annual and lifetime fishing licenses via its website, ncwildlife.org. Short-term licenses cost $6 for coastal fishing and $9 for inland fishing; annual runs $16 for coastal, $25 for inland and $41 for combined. Lifetime licenses cost $16 to $477 depending on age and type of fishing. Kids under 16 don’t need a license.

KAYAKING

A Coast Guard-approved life vest must be available for each occupant, and anyone under 13 has to wear one at all times. You don’t need a license to use an unmotorized kayak or canoe. If yours does have a motor, you have to register it with the state and complete a boating safety education course. (More info: ncwildlife.org.)

CLIMBING AND HIKING

In state parks, rock climbers have to register at park o ces or at access points for climbing and rappelling permits. All climbers under 18 need parents or guardians to sign their permits. The N.C. Division of Parks and Recreation doesn’t o er instruction or supervision for climbers, so equipment and training is your responsibility.

STATE PARKS

The State Parks system includes 34 parks, four recreational areas, and three natural areas, each of which has its own specific rules for fishing, kayaking, and climbing. But a few rules apply at all 41 locations: camping in designated areas only; vehicles on-site after park hours must be registered; no alcohol; and pets on leashes at all times.

DR E AMCharlotte :

ARECREATIONIST ’S

For Love of Lake Norman

BY GREG LACOUR AND ANDY SMITH

“LAKE NORMAN” can refer to either the actual lake or the area that surrounds it—the collection of northern Mecklenburg and southern Iredell County cities and towns, the spaces between them and the new homes, piers, and boat docks built at or near the water’s edge. That’s the new Lake Norman, all right. We’ve got three ways for you to get the most out of Lake Norman’s charms and get back to nature: by visiting a waterside park, water recreation and cruising the lake in style. Let’s get started.

A VISIT TO LAKE NORMAN STATE PARK (AND OTHERS)

Even boomtowns have oases. Here’s Lake Norman’s biggest: nearly 2,000 acres of pines and mixed hardwoods, 30 miles of mountain biking and hiking trails, a 125- yard sandy beach, and 32 sites for camping—and, of course, fi shing. The state park (759 State Park Road, Troutman) opened in 1962 after Duke Power donated the land, and the lake’s sediment-rich waters teem with crappie, perch, bass, and channel catfi sh.

The park, about a 45-minute drive from Charlotte, hugs the northern edge of the lake near Troutman, and trails meander along the edges of coves and inlets.

If you don’t need the expanse or care to drive that far, check out any of a trio of local parks in Cornelius: Ramsey Creek Park (18441 Nantz Road), with its 44-acre waterfront area; Jetton Park (19000 Jetton Road), with its reservable decks and gazebos; and Robbins Park (17738 W. Catawba Ave.), a newer o ering with a disc golf course and an expansive play area for kids.

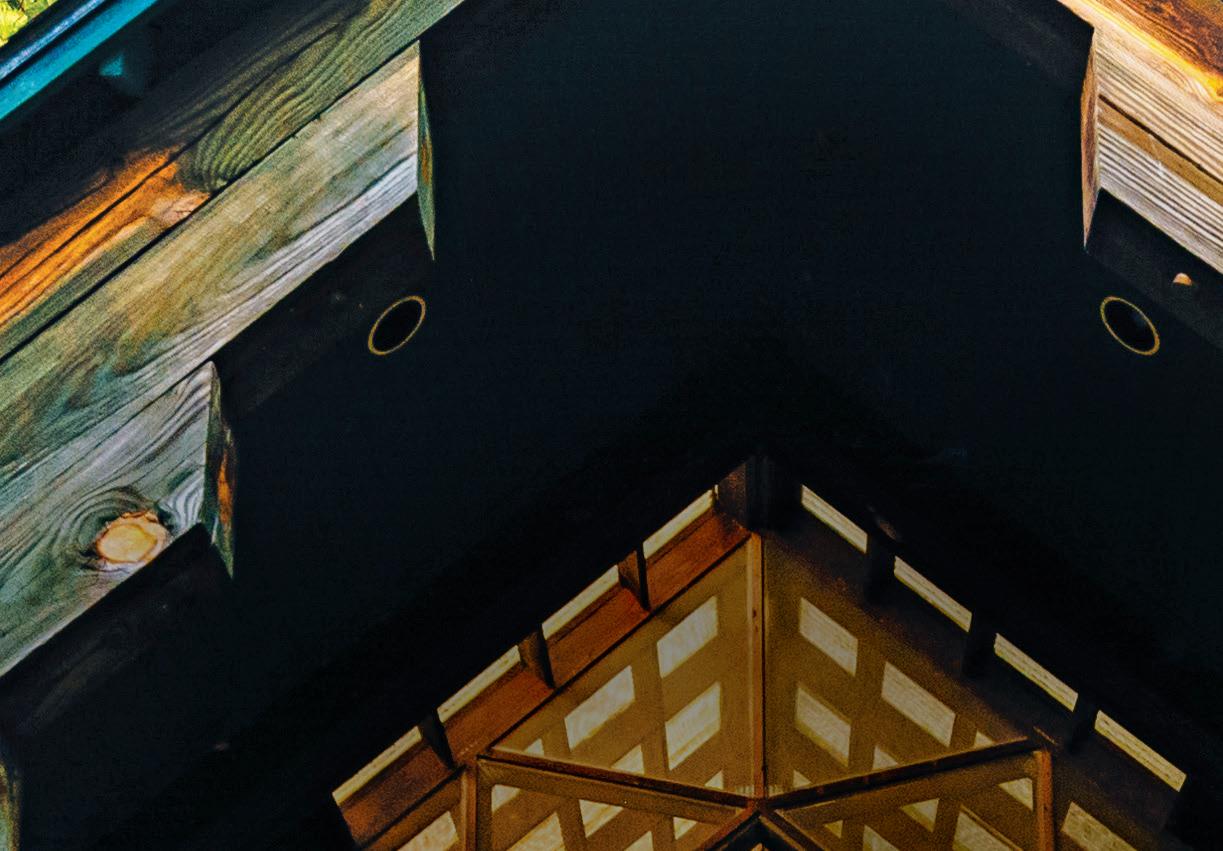

Opening spread: A pavilion at Jetton Park. Opposite page: Lake Norman is nicknamed North Carolina’s “Inland Sea” due to its 520 miles of shoreline. This page from left: Queens Landing’s Lady of the Lake and Catawba Queen; a man waterskis on Lake Norman.

DR E AMCharlotte :

ARECREATIONIST ’S

OUT ON THE WATER Get Educated at the Ride LKN Wake & Surf School

The instructors at this school (114 Bowfin Circle, Mooresville) tailor lessons in wakeboarding, wakesurfing and wakefoiling to people of varying skill levels, from newcomers to riders ready for pro tricks. The business also o ers private charters and summer camps for kids, with tubing, wakeboarding and surfing lessons.

On Board with Aloha Paddle Sports

This waterfront shop (400B N. Harbor Place, Davidson) at North Harbor Landing in Davidson rents kayaks, too, but it specializes in paddleboarding. A private introductory lesson costs $60 ($35 for ages 10-16), and Aloha also o ers paddleboard yoga and 90-minute sunset paddle tours. It’s a lake, so don’t worry about surf, but watch those boat wakes.

ESSENTIAL BOAT TOURS ON LAKE NORMAN

Queens Landing: This cruise service operates two boats with dining included: the luxurious The Lady of the Lake yacht or the replica Mississippi riverboat The Catawba Queen. (1459 River Highway, Mooresville)

Captain Gus’ Lake Norman Laugh Liner: Think the Funny Bus on water. Capt. Gus Gustafson is a published author and an ideal fishing partner. (Little Creek Access Area, 4880 Burton Lane, Denver) Charlotte Cycleboats: This party boat experience, highly popular for bachelorette shindigs, gives you the chance to work o those drinks by powering the vessel together. If you hear lots of yelling on the lake, it’s probably this boat. (400B N. Harbor Place Drive, Davidson)

Celebrate on Lake Norman’s Biggest Yacht: Carolina Grace, a 100-foot luxury yacht and event venue, is the largest vessel of its kind on the lake. It’s outfitted with two bars, o ces, four bathrooms, a heated upper deck and room for more than 100 guests, which makes it a coveted wedding venue. But it o ers intimate experiences, too, like dinner cruises and yoga classes. (18020 Kings Point Drive, Cornelius)

BIRDER’S-EYE VIEW

When the pandemic struck, thousands discovered the physical, mental, and ecological benefits of birding. Now is the perfect time to join the flock.

BY ALLISON BRADEN

In Spring 2020, people around the world noticed neighbors they never knew they had. As the coronavirus ground our normal lives to a halt, robins busied themselves laying bright blue eggs, and rose-breasted grosbeaks decked themselves in red and black to attract mates. Sales of binoculars and birdfeeders spiked, and new birdwatchers discovered that the birds on the periphery of our lives have a complex community of their own—plus the sense of emotional and physical well-being that comes from getting outside and focusing outward.

“Hope,” as Emily Dickinson wrote, “is the thing with feathers.” Flowers may bloom brighter, saturated with our relief as the pandemic winds down, but the joy of getting to know our wild neighbors will outlast quarantine. It’s never been easier to learn about local bird life, and birding can prove surprisingly fun and rewarding. (It has all the thrill and suspense of hunting—with less mess.) And the benefits go both ways. Close attention to birds and their habitats is a step toward healing the damage we’ve done to their populations, even as we heal from the damage we’ve done to ours.

The mid-December sun glints o a frosty field as I pull into the parking lot at McAlpine Creek Park. A small group clusters around a pair of cars adorned with bird bumper stickers. They’re bundled against the cold, but when they all

This page from top: Indigo Buntings like to perch on branches and telephone wires; Eastern Phoebes are known for their tail flicks. Opposite page: Eastern Towhees (a female is seen here) like to rummage in undergrowth.

lift their binoculars to look at a hawk perched on a distant pole, I know I’m in the right place.

The Mecklenburg Audubon Society o ers bird walks in the Charlotte region year-round. Judy Walker, the MAS newsletter moderator and a retired UNC Charlotte education librarian, will lead our group of nine on a stroll in search of species that have migrated here for the winter, like fox sparrows. One member of our group is new to the area, and he’s especially eager to spot a winter wren, a tiny bird with a big voice.

Walker has led bird walks for about 20 years, and she’s been birding for 20 years longer than that. She’s seen nearly every feathered species there is around here, but her enthusiasm hasn’t waned. “I get excited about things,” she says, “but it’s getting other people excited.” Her favorite way to capture a beginner’s interest is to spot a new-to-them bird or what she calls a “wow” bird. We set o from the parking lot at a birder’s typically glacial pace, pausing often to listen for chirps and peer at the leafless treetops.

Walker stops at a pile of brush and explains that this is the habitat winter wrens prefer. She pulls out her phone and plays the bird’s call. The group hushes. We hear an answer deep in the brush but don’t see the bird. As we move on and Walker explains the distinction between the goldfinches and pine siskins gathered on the gravel, it’s easy to believe that the birds in our area are doing fine. Lauren Pharr sets me straight.

Pharr, 24, studied the e ects of urbanization on birds for her master’s in fisheries, wildlife, and conservation biology at N.C. State, and she says light and noise pollution and global warming have devastated bird populations. “Light pollution that comes from our

SPOTS TO BIRD

DR E AMCharlotte :

ARECREATIONIST ’S

MCALPINE CREEK: The wide gravel trails o er vantages on woods and wetlands. Several rarities, including a roseate spoonbill, stopped by the “beaver pond” behind the main pond last year. But no need to hold out for something exotic. Listen for the hoot of the resident barred owls.

FOUR MILE CREEK GREENWAY: This 2-mile paved greenway in south Charlotte is usually home to a flurry of bird activity. Listen for birdsong in the tangles of brush that line the path. In the spring, Walker says, beginners will take in good sightings on any of Charlotte’s greenways. Take a stroll before work to avoid weekend crowds.

MCDOWELL NATURE PRESERVE: This preserve protects habitats for more than 100 species. The Piedmont Prairie Trail winds through a grassy landscape uncommon in urban Charlotte. Visit soon after dawn for a glimpse of spring migrants like rose-breasted grosbeaks and indigo buntings.

WITH A GROUP: “If you want to get outside and start learning more about birds and start identifying birds by sight and by sounds,” Pharr says, “it’s good to go out with someone who’s more experienced.” Sign up for one of Mecklenburg Audubon Society’s weekly walks to learn birding skills and etiquette, such as how to visit bird habitats respectfully.

At left: Barred owls can be seen—and heard— at McAlpine Creek.

headlights, from street posts, illuminated buildings— all that goes into something that we call ‘skyglow,’ and it’s like a blanket over the sky,” she explains, which makes it harder for birds to navigate and a ects everything from migration to reproduction. Uptown’s dazzling light displays are less beautiful from a bird’s point of view: In 2020, Audubon North Carolina successfully lobbied the Duke Energy Center to turn o unnecessary lights during peak migration. The skyscraper’s springtime darkness sends its own message: Our community extends beyond ourselves.

But to understand the birds’ cloud high perspective ,you have to get to know them first—and that’s the fun part. “It’s a puzzle,” Walker says. “You’d be surprised what you might see.”

We stop at a fallen tree, shivering in the shade, and Walker again tries to lure out a wren. Joggers dodge us as we train our gaze on the branches. Suddenly, there he is: a bird no bigger than a pinecone, his short tail cocked at a jaunty angle. The wren brings the quiet woods to life, and the curved glass in our binoculars reveals an intricate pattern of white and walnut brown in his feathers. We hold still. The wren flits briefly to another branch, and then he’s gone.

BIRDS TO SPOT

BLUE JAY: You’ve probably seen a blue jay before, but can you identify its call? Listen for a loud jeer or a melodious flute-like song. Like crows and ravens, blue jays are corvids, one of the most intelligent families of birds. They’ll sometimes mimic hawk calls to scare o songbirds and keep birdfeeders to themselves.

EASTERN PHOEBE: This small bird, brown on top and creamy underneath, is Pharr’s favorite— despite their earsplitting call. “They’re a species of flycatcher, and I love them so much because they do this little tail flick,” she says. “It is the cutest thing I’ve ever seen.”

ROSE-BREASTED GROSBEAK: These dazzlers will often come right to your feeder (they like sunflower seeds). Look for their large pale pink beaks and bold red triangles on the males’ chests. Download Merlin, an app from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, for quick reference and ID help.

INDIGO BUNTING: These brilliant, deep-blue songbirds like to perch on the ends of branches or on telephone wires. Spot them in brushy hedgerows or where forest meets field. Don’t worry about missing them after peak spring migration— you can listen for their cheerful song all summer long.