8 minute read

Chapter 1 – Black Death

1.

Black Death

“What shall I say? How shall I begin? Whither shall I turn? On all sides is sorrow; everywhere is fear. I would, my brother, that I had never been born, or, at least, had died before these times.” Francesco Petrarch, poet/humanist He lost his Laura (d. 1348), his son, Giovanni (d. 1361), and grandson, Francesco (d. 1368), to the bubonic plague

In europe, 1816 is known as ‘The Year There was No Summer’ and in New England it is remembered as ‘Eighteen Hundred and Froze to Death.’ Snow fell on Quebec City in the colony of Lower Canada, today the province of Quebec, in June. That same month, the Romantic poet Byron was hosting guests at Villa Diodati on Lake Geneva. Prevented by cold, wet, windy weather from enjoying the planned outdoor pursuits and trapped indoors the group was, unintentionally, socially isolating. To relieve the boredom, Byron challenged his guests to compose gothic tales of horror. Days later, on the night of June 16-17 [astronomers have confirmed the date based on a diary entry and the phases of the moon], one of his guests had the germ of an idea for a story entitled, ‘The Modern

black death

Prometheus’. That guest was Mary Shelley and the tale, the most widely recognised in the horror pantheon, known by the name of the monster’s creator, is Frankenstein.

Almost five centuries earlier the Florentine scholar Giovanni Boccaccio set his work The Decameron in a country villa near Fiesole, on a hillside a short distance northeast of Florence. Ten friends tell tales to one another while socially distancing, sequestered from a terrifying plague ravaging Florence in 1348. Boccaccio, a sterner taskmaster than Byron, demands from each one tale every night for ten nights. Setting the stage, the framing story includes a gruesome description of the illness: “[T]here appeared certain tumors in the groin or under the arm-pits, some as big as a small apple, others as an egg; and afterwards purple spots in most parts of the body; in some cases large and but few in number, in others smaller and more numerous – both sorts the usual messengers of death.”

This 14th century outbreak was the second great pandemic to sweep through Europe. The first had come in the middle of the 6th century, ravaging Constantinople and spread by ship around the coast of the Mediterranean. At its peak, 5000 people a day were dying in Constantinople, with the population ultimately halved. Overall, it is estimated that 25% of the Mediterranean world was wiped out in the first plague pandemic.

But that paled in comparison to the disease from which Boccaccio and his friends were sheltering – bubonic plague. It was highly infectious, virulent and killed its host quickly, features that made it all the more terrifying. It struck across all social classes, not preferentially targeting the poor, and attacked the hale and hearty as well as children and the elderly. It swiftly earned the sobriquet, ‘the Black Death.’

The Black Death entered Europe aboard Genoese ships through Messina in Sicily and the ports of northern Italy. Florence was one of the first cities severely afflicted. Eventually, more than three-quarters of the population would die in one of Europe’s first, and worst, hit cities.

Quantitatively and qualitatively it was the granddaddy of all pandemics. It killed a larger proportion of the European population than any other and had a more profound effect on society, culture and spirituality than any of the pandemic that followed. It also hung around for four centuries, recurring generation after generation. The last outbreak of the Black Death in Europe,

life after covid-19

bookending the first, also occurred in Messina, in 1743, 396 years after it first arrived there. For these reasons pandemic scholar Frank Snowden describes it as “the inescapable reference point in any discussion of infectious diseases and their impact on society … setting the standard by which other epidemics would be judged.”

The origins of the bubonic plague, a disease caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, like much of the distant mirror that is the 14th century, are shrouded in myths buried under a misnomer. The bacteria is an eponym. It carries the surname of its discoverer, Alexandre Yersin – a dubious honour indeed. Contemporaries referred to the medical catastrophe it wrought as atra mors. The latter, meaning death, is evident in terms such as rigor mortis and mortuary. However, the first term, atra, has multiple meanings, including both black and terrible. Recent scholarship and textual analysis has reached a consensus that the reference is to the ‘Terrible Death’, not the ‘Black Death’. Regardless, throughout, in the interests of convenience and convention, the events of 1346 to 1353 will be referred to as the Black Death. That said, contemporary references to ‘the terrible death’ speak to its psychological impact.

The Black Death’s foundational myth requires more rigorous analysis. Its source is Gabriele de Mussi, a notary from Piacenza, north of Genoa. He described events in Kaffa (Feodosia), a Genoese trading outpost on the Black Sea coast of the Crimea when plague broke out in 1346 in Istoria de Morbo sive Mortalitate quae fuit Anno Dni MCCCXLVIII (History of the Disease, OR The Great Dying of the Year of our Lord 1348). At the time, the Crimea was part of the Golden Horde, the northwestern portion of the Mongol empire, and relations between the Genoese and the Mongols were terrible. Janibeg, the Khan, had besieged the colony since 1343. In 1344 an Italian relief expedition broke the siege and a year later an epidemic forced Janibeg to abandon his attempt to take the colony. In the winter of 1347-48, a second epidemic threatened yet another besieging force led by the Khan. De Mussi wrote, “But behold, the whole army was affected by a disease which overran the Tartars and killed thousands upon thousands every day. It was as though arrows were raining down from heaven to strike and crush the Tartars’ arrogance.” Arrows, the imagery of infection, and their origin, ‘raining down from heaven’, are both noteworthy.

black death

This time, according to de Mussi, Janibeg took desperate measures and “ordered corpses to be placed in catapults [actually, trebuchet] and lobbed into the city in the hope that the intolerable stench would kill everyone inside.” In one fell swoop he freed himself of the need to dispose of the bodies and infected the Genoese garrison. He is credited with the first use of biological weapons in recorded history.

According to Guardian contributor Simon Wessely, the incident never happened and de Mussi is guilty of hyperbole, “using the story as medieval tabloid journalism to illustrate Mongol frightfulness and corpse desecration.” On the other hand, American microbiologist Mark Wheelis concludes the “theory is consistent with the technology of the times and with contemporary notions of disease causation.” In other words it could be true. However, true or not, he goes on to declare it redundant; “the entry of plague into Europe from the Crimea likely occurred independent of this event.” Simply put, it did not require airborne cadavers to infect the Genoese in Kaffa.

Kaffa was located near the Straits of Kerch between the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov. River boats bringing Oriental goods down the Don River from the Great Silk Road’s terminus in central Russia would trade their goods in Kaffa. There, Genoese merchants would transfer the goods onto ships bound for Genoa and other European ports. Oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis) bearing black rats (Rattus rattus) would have accompanied the ships and goods. Above and beyond biological warfare, there were a multitude of connections between Europe and Asia via the Black Sea that would have transmitted the infection to Europe. While the precise methods of travel are unclear, the route is not. Bubonic plague travelled along the Great Silk Road from Asia into central Russia, down the Don River to Kaffa and thence onward to Europe.

Located on the Sea of Marmora between the Black and Mediterranean Seas, Constantinople was infected first, in the early summer of 1347. Messina, the seaport in Sicily, and the northern Italian ports followed. Simultaneously, the plague erupted in North Africa, at the Egyptian port of Alexandria. By the fall it had reached Marseilles, headed up the Rhône and crossed overland towards Bordeaux. The following spring, aboard a ship from Bordeaux it arrived in England at Weymouth and Bristol. By August 1348 it had reached

This pesky little critter, Rattus rattus, carried the Xenopsylla cheopis (Oriental rat flea) that carried Yersinia pestis (bubonic plague bacteria) into Europe in 1347.

The plague of Florence in 1348, as described in Boccaccio’s The Decameron. Etching by Luigi Sabatelli the Elder (1772-1850).

The Abbess from Hans Holbein’s Simolachri, Historie, e Figure de la Morte, 1549. Despite her religiosity and her rosary even the Abbess must come when death calls.

“I suppose the world has heard of the famous Solomon Eagle an enthusiast: he tho’ not infected at all, but in his head; went about denouncing of judgement upon the city in a frightful manner; sometimes quite naked, and with a pan of burning charcoal on his head.” –Daniel Defoe

Two women lying dead in a London street during the great plague, 1665, one with a child who is still alive. Etching after R. Pollard II.

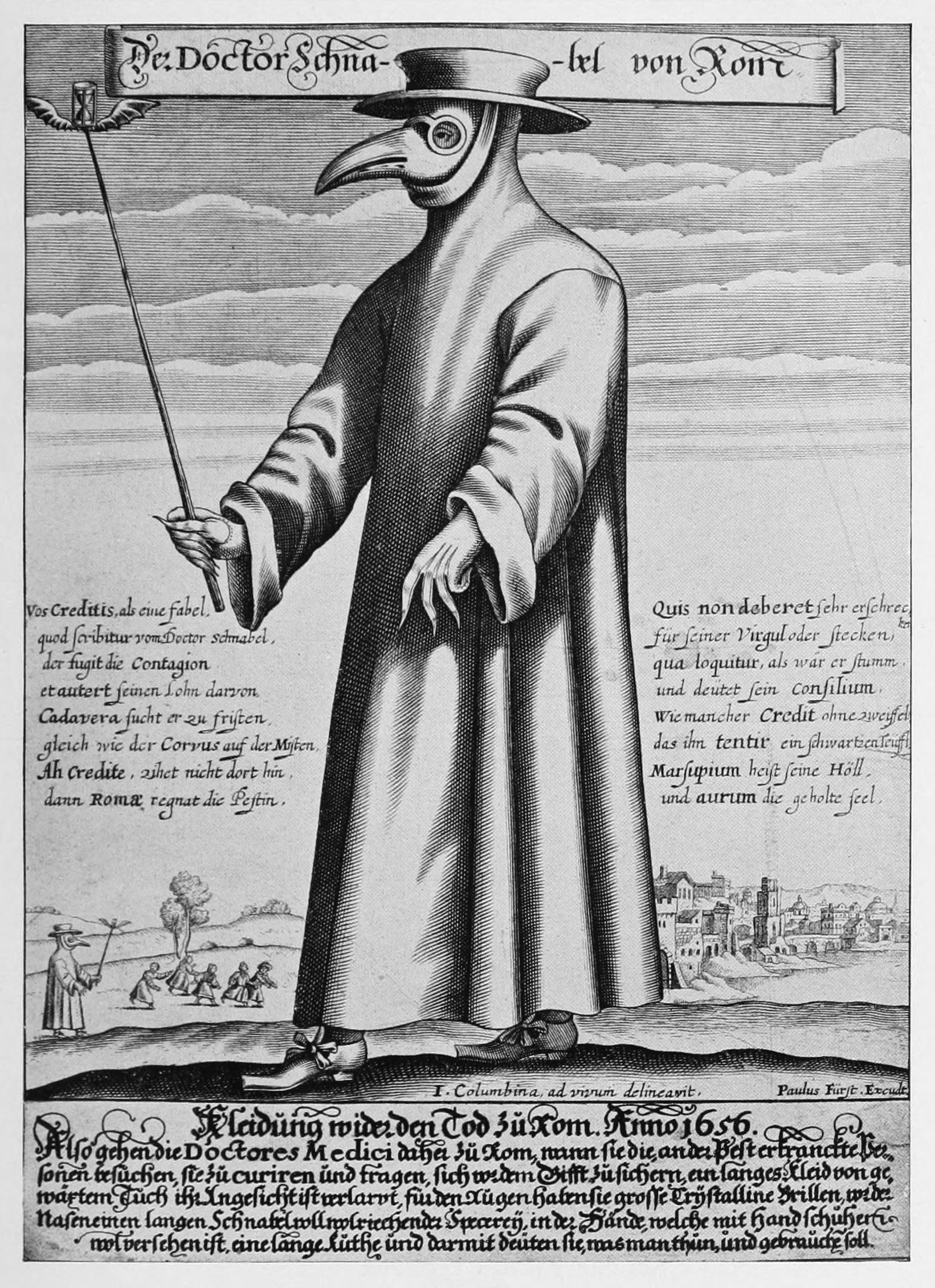

Paul Fürst, engraving, c. 1721, of a plague doctor of Marseilles (introduced as ‘Dr Beaky of Rome’). His nose-case is filled with herbal material to keep off the plague.