Russian Bombers

David Baker

David Baker

Published in Great Britain by Tempest Books an imprint of Mortons Books Ltd.

Media Centre

Morton Way

Horncastle LN9 6JR

www.mortonsbooks.co.uk

Copyright © Tempest Books, 2023

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording, or any information storage retrieval system without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-911704-13-3

The right of David Baker to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Typeset by: Druck Media Pvt. Ltd.

CLUTCHING AT STRAWS

The Second World War was fought by the Soviet Union in response to Operation Barbarossa, beginning on 22 June 1941, when Nazi Germany launched the largest land invasion in history against the USSR. For Russians, it was a defensive war that lasted four years. During that time Soviet forces reversed the early successes of the Wehrmacht and pursued German troops across Eastern Europe all the way from the outskirts of Moscow to the Reichstag in Berlin, a distance of 1,600km (1,000 miles).

This incredible fightback had been accomplished largely without the use of long-range bombers able to deliver strategic retribution. Unlike most European powers with large air forces, Russia had not been successful in developing heavy bombers.

It was not for lack of trying though. Attempts had been made to develop a strategic bombing capability from the days of the Imperial Russian Air Service, before the Bolshevik revolution of 1917, right up to the war itself. The revolution had triggered a reconsolidation of former Tsarist air units to deal with the threat posed by White Russian air elements fighting to overthrow the Soviets.

As part of a general move to expand the industrialisation of Russia, aircraft production was expanded and output increased significantly during the 1930s. But that stalled when the successful commander of Soviet air forces, General Yakov Alksnis, was imprisoned during the Stalinist purges. The Commissariat for the Aviation Industry had responsibility for organising the expansion of aeronautical engineering and aircraft

production but in 1940 its leader, M. M. Kaganovich, shot himself because of the purges. His place was taken by A. I. Shakurin, who held the position for the duration of the war.

By the end of the war, despite the political purges, the mass industrialisation of the USSR had enabled the aviation industry to expand immensely – with production rising to 40,000 aircraft annually. Of these, more than 80% were single-engine types and all had piston engines. This dearth of multi-engine types reflected an emphasis on defensive fighters and ground attack aircraft to support the army across its broad war-fighting front line which, at its fullest extent, stretched from the Baltic to the Black Sea.

Soviet air power played a seminal role in tactical operations, destroying German tanks, ground equipment, artillery positions, munitions and supply dumps on or close to the front line – but efforts to produce long-range bombers for strikes deep within enemy territory were never fully extinguished. Before the war, Stalin looked to long-range aviation as a useful propaganda tool – just as Hitler would do

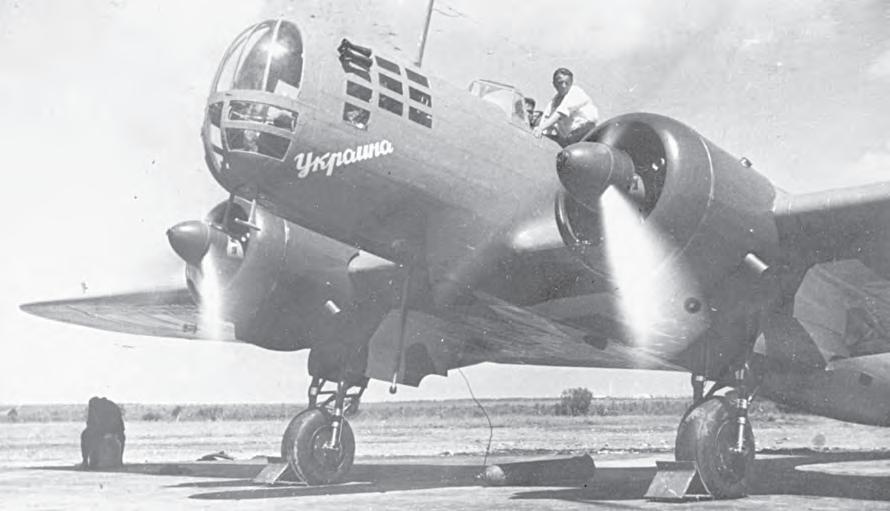

with aircraft such as the Focke-Wulf Fw 200 – and this opened funds which would otherwise have been blocked for the development of such machines. This resulted in the Ilyushin DB-3 (TsKB-26) and 3A in 1936, used to great effect in showcasing Soviet capabilities. Developing aircraft for publicity and propaganda was not the surest route to creating a successful combat aircraft but the Ilyushin was nevertheless a moderately useful bomber capable of carrying a 1,000kg (2,200lb) bomb load a distance of 4,000km (2,485 miles) or 2,495kg (5,500lb) over shorter distances.

It could even be regarded as superior to the Luftwaffe’s Heinkel He 111; the DB-3B had a greater range and more effective defensive armament. It was this type which became the first Soviet aircraft to attack Berlin, in a raid on the night of 7-8 August 1941. This was but the first in an extended series of Soviet bombing raids on the German capital, following the first raid by the French in June 1940 and then the British from August 1940. Over the course of several weeks during the second half of 1941, Soviet bombers based on islands in the Baltic and in Estonia dropped 36,000kg (79,000lb) of bombs on Berlin.

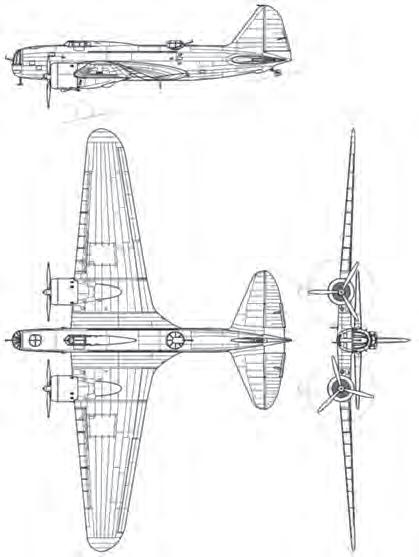

The defensive armament of the Ilyushin DB-3 was provided in nose and dorsal positions but the type of weapon carried varied between 62mm machine guns and 20mm cannon, according to operating units. (Kaboldy)

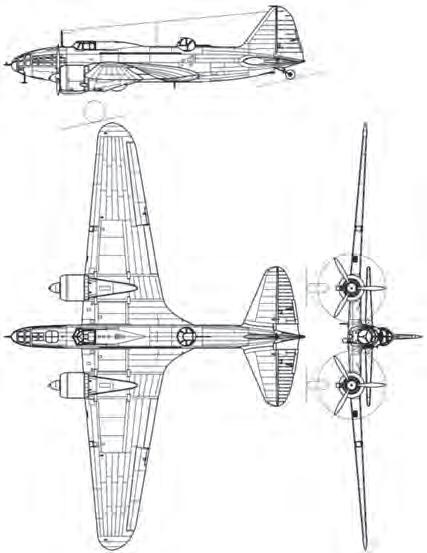

The Il-4 had improved defensive armament but used the same engines as the DB-3 with no overall performance improvement. (Kaboldy)

Ilyushin made around 6,700 DB-3 types and a developed version, the Il-4, but as German troops swept east – overrunning airfields – the opportunity

to attack Germany receded and the Soviet Union began using medium and long-range bombers for close support operations instead. But Ilyushin was not alone in seeking to provide the USSR with longrange bombers.

Graduating from the Taganrog Technical School, Vladimir Mikhailovich Petlyakov joined the Tsentral’nyy Aerogidrodinamicheskiy Institut, or TsAGI, the Central State Aerodynamic and Hydrodynamic Institute in 1920. After the customary imprisonment under the universal purges of the 1930s, Petlyakov was set to work on Project 100, which would become the Petlyakov Pe-2. This was one of the most famous Russian aircraft of the war; a long-range, twin-engine fighter pressed into a ground-attack and close-support combat role.

His design bureau, Petlyakov OKB, also worked on a four-engine long-range bomber design, initially designated TB-7, which would become the Pe-8. Petlyakov’s incarceration, along with Andrey Tupolev, compromised the Pe-8’s development but it made its first flight in July 1938. Plagued by Soviet bureaucracy and persistent technical problems with successive engine types, the giant aircraft entered slow production in 1940 but only one squadron was equipped with the type when the Germans attacked in June 1941 they were not combat-ready.

Essentially a mid-wing monoplane of all-metal, stressed-skin construction, the Pe-8 bristled with defensive firepower including a 20mm (0.79in) ShVAK cannon in the nose, a dorsal gun position with a 7.62mm (0.30in) ShKAS machine gun and another of the same type in a ventral turret. A tail gunner had a ShVAK cannon in a powered turret and a manually operated UBT machine gun was housed in each inboard engine nacelle, accessed through the wing. The Pe-8 had an internal bomb load of 4,000kg (8,800lb) with two 500kg (1,100lb) bombs, one under each wing.

With a crew of 11, the Pe-8 had a range of 3,700km (2,300 miles) but a top speed of only 443km/h (275mph). Although kept in operational use throughout the war, fewer than 100 were produced and the type was increasingly assigned to tactical support operations and bombing raids against German depots in occupied territory. Nevertheless, some raids were conducted against Finland and Estonia as well as against German forces occupying beleaguered Russian cities. It was Russia’s only fourengine bomber in active service during the Second World War.

Fabricated primarily from duralumin, the Pe-8 saw only limited use and fewer than 100 were built, the type being involved in experimental engine trials after the war. (Author’s collection)

The Soviets’ desire for a strategic bomber increased considerably, however, when it became clear how successful the four-engine bomber fleets operated by the RAF and USAAF had been in striking at strategic targets within Germany. A new development programme for a long-range, four-engine bomber with high altitude and high speed capabilities was launched in 1943. Three design bureaus, led by Vladimir M. Myasishchev, Andrey Tupolev and Iosif F. Nezval were tasked with producing designs. By this time the Russians had also been made aware of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress through the ill-advised boasting of Edward V. Rickenbacker during a special mission to the USSR. On 19 July 1943, General Belyaev, chief of the military mission to the US, requested that this type be included in the Lend-Lease programme, which was already providing American aircraft to Russia.

Compromised by the incarceration of Petlyakov, the only four-engine, long-range bomber available to the Russians during the 1941-45 war was the Pe-8, this example bringing foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov to RAF Tealing, Scotland, on 20 May 1942 for the signing of the Anglo-Russian Treaty six days later.

(World War Photos)

The request was refused only to be reiterated on 28 May 1945, three weeks after the end of the war in Europe, on the pretext that they would be needed in forthcoming raids against Japan. The Russians wanted at least 120 B-29s, but the Americans again refused. This only encouraged the Soviet government to press ahead determinedly with plans for an equivalent Russian-made design. Meanwhile, Tupolev was well

Design work on the Myasishchev DVB-202 long-range bomber began in 1944 but further work in 1945 focused on the DVB-203, which was similarly unsuccessful. (via Tony Buttler)

along with the development programme begun in 1943. Competing concepts from Myasishchev, such as the DVB-202, and Nezval were also under way but they were unsuccessful, as was the Il-14 from Ilyushin.

With Dimitry Markov in charge of design, the Tupolev design bureau (Opytnoe Konstrutorskoe Byuro – OKB for short) had begun work on what was designated Aircraft 64 in September 1943, shortly after the rejection of Russia’s request for B-29s. The intention was to produce a fully pressurised, high altitude bomber with a bombload of 18,000kg (39,683lb), a speed of 500km/h (311mph) and a range of up to 6,000km (3,729 miles). The Russians had never produced anything approaching this capability and were highly motivated by the impending operational debut of the B-29. The initial design that emerged had a length of 29.975m (98.3ft),

a wingspan of 42m (137.75ft), a maximum speed of 600km/h (373mph), a cruising speed of 400km/h (249mph) and a ceiling of 12,000m (39,370ft).

The monocoque structure employed conventional manufacturing techniques with stressed skins and high-lift devices on the wings, each of which incorporated two spars. At this stage the tail consisted of two vertical stabilisers. There were four different engine options, including three liquid-cooled types and a radial, the Shvetsov ASh-83FN. The bombload was to be carried in two bays separated by the carrythrough wing centre-section with comprehensive defensive armament provided by four turrets equipped with 23mm (0.9in) cannon.

After several months of initial design studies, overall weight was becoming a problem so in mid1944 the overall concept was reduced in size. This

resulted in a lower maximum ceiling of 11,000m (36,089ft). In August 1944 a further compromise was necessary when the requirement was amended to include photo-reconnaissance capability. Worse still, a derivative was now required that could carry 72 fully-equipped troops or a mixed load of military vehicles potentially including a T-60 light tank.

In the subsequent redesign the armament was reconfigured to four twin-gun turrets with cannon and a tail turret with optional guns. A full-scale mock-up was inspected in September 1944 but there were clear shortcomings including the absence of a bomb-aiming radar, which was now specified. Crew complement increased to 10 with the addition of a radar-operator for the new bomb-aiming system and final approval for construction was granted on 27 April 1945. The engines were to be Mikulin AM-43s or AM-46s, with TK-300 turbosuperchargers. In this iteration, maximum range was predicted to be 5,000km (11,023 miles) with an 18,000kg (39,683lb) bomb load.

By this time, the Soviet aircraft industry had become a vast machine dedicated to supplying wartime production needs. Projects that would not become operational for at least two years necessarily had to take a back seat when it came to the allocation of manpower and resources – including Aircraft 64.

There was also a lack of development in new materials, emergent technologies, sophisticated electrical systems and new integrated bomb-aiming and navigation equipment. The Aircraft 64 project consequently became bogged down by technical obstacles, resulting in spiralling delays.

Meanwhile, three B-29s (serial numbers 42-6256 ‘Ramp Tramp’, 42-6365 ‘General H. H. Arnold Special’ and 42-6358 ‘Ding Hao’) had been impounded after force-landing on Russian territory following raids on Japanese cities in July, August and November 1944. The wreckage of a fourth – 42-93829 ‘Cait Paomat II’ – was also recovered for study.

At the time Russia was not at war with Japan and this was the excuse made for not returning them.