15 minute read

Disregarded Artist

n the late 1980s, Jim Engh found himself stranded on a country road in Latvia, in a territory still under Soviet control, waiting for a ride that wasn’t coming. I

Engh had spent the day in the woods, hiking several hundred acres of property for a potential client interested in building a large golf resort. Now, tired and slightly afraid, he simply wanted to return to the safety of his hotel. These were “cowboy days” in Eastern Europe, says Engh, who at the time oversaw design and construction for an arm of Mark McCormack’s London-based IMG Developments. The fact that he’d been forgotten and left to hitchhike back to Riga led him to believe this exploratory project was likely going nowhere. Before departing, however, Engh returned to the site and quickly “designed” a course, hurriedly marking out the holes. “I basically did the 54-stakes-in-the-ground thing for them—here’s a tee, here’s the landing area, here’s the green. Repeat,” he says. “I said, ‘Here’s your golf course—go mow it, cut a hole.” He laughs. “Who says I can’t do minimalist?” The joke, of course, is that Engh would later gain fame for building golf courses that were aggressively non-minimalist. He became known as an impresario of golf visions, an artist who admits to pushing the boundaries of creativity. His courses look and play like Candylands decorated with steep slopes and bowls, soaring elevated tees and squiggly lines. Trees often stand in the middle of fairways—or in bunkers. Greens can appear to be moving, sliding down terraced landforms like emerald goop. Fairways expand like pregnant

abdomens, then cinch suddenly into insect waists. He has pumped waterfalls through actual erosion fissures found in rock escarpments, melding artifice with nature. He once built an entire golf course with no bunkers, an idea that, over a decade later, is suddenly on trend. He once constructed a hole with three greens.

Clients and golfers—at least many golfers—loved it. From the late 1990s through the late 2000s, Jim Engh was arguably the hottest golf-course architect in the

world. He ran a small operation out of his office near Denver and typically had only one or two projects under construction at a time. Remarkably, 11 out of the 16 full-size courses he opened from 1997-2007 placed on Golf Digest’s Best New Courses lists.

In 1997, Sanctuary Golf Course, in Colorado, was named the best new private course. He then won first place three more times in different categories, consecutively, with The Club at Redlands Mesa (2001), Tullymore Golf Club (2002) and The Golf Club at Black Rock (2003). Another course, Fossil Trace, fraction

georgia beauty

The par-4 fifth at The Creek Club at Reynolds Lake Oconee in Greensboro, Ga. ally missed a fifth win. In 2003, Golf Digest gave Engh its inaugural Architect of the Year award, and for several cycles, three of his courses were ranked by our panelists among America’s 100 Greatest Courses.

Engh rode the momentum and parlayed one success into another. “Jim can be a super-fun guy to be around—clients really liked his energy, and he was passionate,” says Mitch Scarborough, who worked as Engh’s associate from 1999 until 2016. “You could just feel it. It may not be the easiest site in the world, but they knew he was going to turn it into a unique golf course.”

“For years and years, Jim was attracting the clients who wanted headlines in Golf Digest,” says fellow architect Rick Phelps. “They wanted the pictures spread all over the place, which they were. His courses were extremely photogenic, and that led to more press coverage.”

“We didn’t really have any courses during that time that didn’t get some type of recognition,” Scarborough says.

In 2007, Engh opened The Creek Club at Reynolds Lake Oconee in Georgia, and Four Mile Ranch in Colorado, two acclaimed courses that he considers perhaps his best work, the fullest realisation of his design ideals. But in the 13 years since, he has completed only two courses in the United States, and none since 2015, a stunning turn of events considering how prominent he was. A number of factors have played into his relative disassociation from American golf-course design, including the recession of 2008-’09 and the scarcity of new course development, but simple answers don’t adequately explain: What happened to Jim Engh?

‘TRYING TO EVOKE AN EMOTION’

developers didn’t hire Engh because he built great golf courses—they hired him because he built some of the most extraordinary, original courses ever conceived. His designs were unmistakable, orchestral bursts of Seussian triumphalism. In a profession that usually plays follow-the-leader, with shapes and styles derived from the day’s popular movements or, as is currently in vogue, the past, Jim Engh’s courses seemed to come out of nowhere, other than his imagination.

“We wanted that from him,” says Bob Mauragas, who was vice president of golf operations at Reynolds Lake Oconee when

Engh was hired there. “We wanted that sexy, really dynamic-looking course. . . . Something that was really, really cool. Jim Engh designed the Tesla of golf courses before anybody ever thought of it.”

In instructional terms, Engh owned his swing. The vernacular he created was personal, riven with sculpted banks, flowing lines and his patented “muscle bunkers”—deep gashes with knobby grass walls aligned like knuckles. Holes could be “weird” or “goofy,” to use his words, or full of whimsy: Behold a green nestled in a bowl of rocks above a reflection pond; behold tall sandstone “fins” protruding from the fairway, ready to ping golf balls like an arcade game.

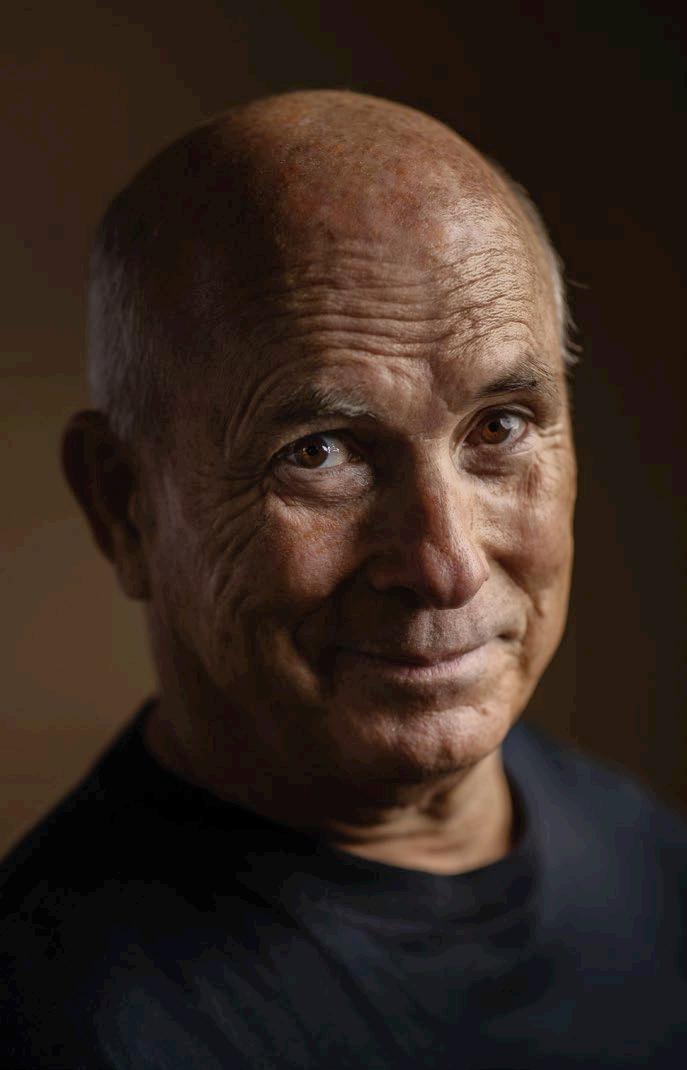

“My ultimate goal is to make people giggle,” Engh, now 61, told me. “That’s what inspires. To get into someone’s heart and into their soul, you have to make them laugh.”

From early on, his architectural motives were driven by a desire to replicate the physical and spiritual highs he got from playing links courses in Ireland. But it took years for Engh to figure out what caused these particular sensations—sensations he found nowhere else—and why. It wasn’t enough to fabricate Ireland’s wild dunes and grasses, nor was it practical on the rocky sites he was getting. He could simulate the bounce and run with exaggerated contour, yet that was only a part of it. The missing ingredient was something more psychological.

“I finally understood—I’m trying to invoke an emotion, not the specific structural features,” he says. His designs attempt to deconstruct the total sensorial intake—the colors, the smells, the feelings of success and failure and even fear—and reassemble them into a 360-degree package of stimulation humming on 18 distinct frequencies. The golf would appear nothing like Carne or Enniscrone, but it might produce the same rush. “It became a much, much bigger picture than just a 200-acre golf course,” Engh says.

Spectacle and disorientation are integral to the ex

my ultimate goal is to make people giggle. that’s what inspires me. . . . you have to make them laugh.

perience, but the emotion comes most consequentially

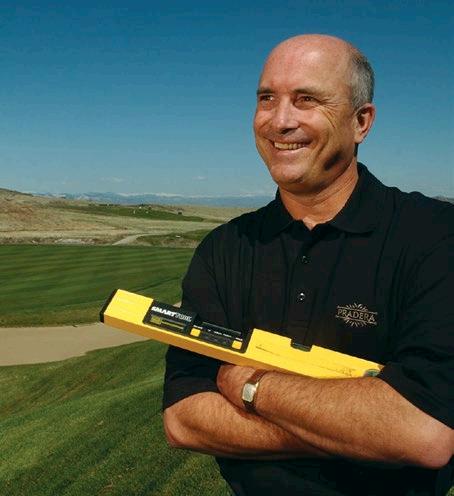

fun with fossils

Above: Golf Digest named the par-5 12th at Fossil Trace in Colorado among the most fun golf holes in America. Right: Engh at The Golf Club at Black Rock. from not knowing how the ball is going to react when it hits the ground, and waiting to see where it ends up once it does. Fairways have concave edges that nudge errors back on line. Blind shots are typically followed by joyous reveals. And bowled greens feed the ball dramatically toward the hole—or past it, up an opposite bank and back close again. Once players are willing to inhabit this mind-set, to think theatrically and allow the ground to do the work, the golf can be thrilling.

“That’s the top of the mountain for me,” Engh says. “Everything I do revolves around trying to re-create a feeling like that in other people.” ▶

developers did hire Engh because he was able to construct golf efficiently, often on difficult or mountainous sites, for surprisingly low costs. (Scarborough says the majority came in between $3 million and $4.5 million.) Engh drafted highly technical line drawings and plans that anticipated every on-site construction maneuver. Though he moved much less earth than his courses suggest, or that his peers often assumed, his ability to detail expenses—from cuts and fills to cartpaths—mitigated costly change orders. (He designed his cartpaths, a rarity in the business, using them as continuously falling sluices that channel water away from the course during rainstorms.)

Though he had returned from Europe in 1991, Engh continued to work abroad, building three courses in China and Thailand. His first solo design in the United States, Sanctuary, was for a private client, David Liniger, co-founder of RE/MAX realty. It was one of the industry’s most audacious debuts. “I came out of nowhere,” Engh says. “I was a big nothing burger until Sanctuary hit the scene. Then everyone was going, What a fluke.” Even though Engh, Liniger and their families had been close friends for years before Sanctuary’s conception, a perception formed that Engh was “just a kid who talked a rich guy into letting him [build the course] as a hobby, a kindness.”

Liniger told me he always intended to hire a “name” designer for the course, and he interviewed six of the top firms in the country. Each looked at the beautiful but severe site south of Denver and said golf there would be too expensive or too impractical. In addition, Liniger says, “I just didn’t like ’em. They were . . . snobbish. Full of themselves.”

Liniger decided to give the job to Engh. He says Engh “watched the project like a hawk” and came in on time and under budget, for less than half as much as the other architects’ projections. “Best decision I ever made,” Liniger says,

“Some people will go, ‘That was lucky as hell,’ ” Engh says. “And I say, ‘Absolutely it was.’ But I had prepared myself to be ready for that situation when it arose.”

His contemporaries looked at the newcomer with interest, and curiosity. “You had to be respectful of the kinds of commissions he was getting,” Tripp Davis says. “The opportunity to do a course at Reynolds is a good gig. The project in Phoenix [Blackstone] was a really good gig. Most everything he did had some high-profile nature to it. He was getting really good clients.”

As Engh’s career began to skyrocket, a different architectural current was taking shape. In 1999, Mike Keiser opened an authentic seaside links at Bandon Dunes Resort on the coast of Oregon, built by another relatively unknown designer, David McLay Kidd. Bandon, and later Pacific Dunes, enthralled the public in the opposite way Engh’s courses did, with subtle, low-profile holes that blanketed the sandy contours of pristine oceanside properties.

In retrospect, it was a fleeting but refreshingly diverse period in American design, when new courses by Engh, Bill Coore, Jack Nicklaus and others could be equally considered and evaluated in their own contexts. Since then, architects and major developers have moved slowly but inexorably toward Bandon-style naturalism and historical replication. Whereas Engh’s ideas arose from his id and a desire to evoke—and even provoke—emotion, prevailing views now insist the greatest attribute a hole can boast is that it was “found” in the land rather than built. Even when courses need to be manufactured, they’re often disguised in prairie-style brush strokes with faux-eroded bunker edging, or formations popularised 100 years ago. Engh’s expressionism came to be seen as gratuitous.

“He was an outlier because he was there all by himself doing something pretty radical compared to what everyone else was doing,” Phelps says.

“If I was really honest, I think it was his style of architecture,” Kidd says. “It’s ex

tremely engineered, and that extremely engineered look has fallen to the wayside the last 20 years.”

At the same time, the entire industry was slowing. Davis suggests that clients looking to develop projects after the economic collapse had more conservative outlooks. “The perception might have been it was smarter to do things that were a little bit more classic in nature, a little bit more substantive instead of just simply unique artistically.”

“Jim was running at a time when everyone was firing from the hip,” Mauragas says. “It was all go-go-go, and then somebody pulled the plug out of the bathtub.”

In 2009, with few domestic prospects, Engh and Scarborough placed a bet on Asia. For several years they traveled the continent to cultivate relationships, and eventually landed three jobs in China, on truly Engh-ian sites. (The designs were “fictional novel kinds of things,” he says.) But when the government began shutting down facilities and construction projects in 2015, Engh came home with nothing but paychecks to show. “It was heartbreaking,” he says.

In the meantime, he refused to seek out remodel and renovation work—the lifeline of almost everyone else in the industry— which he finds creatively limiting after working freely on such grand scales. He also feels an obligation to not compete with younger architects for whom these jobs are more vital. This unwillingness to compromise principle, while noble, abdicated the possibility of keeping his name and material fresh in the eyes of potential clients.

In 2011, Engh completed Awarii Dunes, an actual minimalist but little-seen design on the edge of the Sand Hills in Nebraska, followed four years later by Minot Country Club in his birth state of North Dakota. And though he has built two courses in South Korea and Vietnam during the past five years (and has one in construction two hours southeast of Mexico City), there has been little interest or interaction from American developers.

Toward the end of many hours of discussion, I asked Engh what he was going to do after he finished Cola de Lagarto, the Mexico project.

“I don’t know,” he said. “Maybe I’ll get on a horse and ride into the sunset.”

Could you really not do another golf course again?

“I think so.”

How is that possible?

“Like the mantra that I live by in this business, I always want variety and change. I like seeing different things and doing different things.”

Wouldn’t you at least like one more big project, to go out with a bang?

“I started with a bang.”

He mentioned he might like to be a scuba-diving instructor, but I was reflecting on something he’d said another time, about the need for different experiences in golf: “That’s the beauty of the game—all the variety. To restrict variety is a little narrow-minded. To say that golf has to be done here and here, and not here, I don’t know. When you embrace the fact that there are many different kinds of golf courses, that’s the real beauty of it.”

Most golfers know this, and crave variety. They’re open to experience and want options on the menu. Yet elsewhere, tastes have contracted to the point where there’s little oxygen, or tolerance, for divergent points of view. Influential actors—architects, developers, media—might hold deep convictions that historicism and naturalism best translate the game’s highest aspirations, and perhaps they are correct, but pursuing this as an ideological inevitability comes at the cost of ingenuity and exploration. At that point, golf design is a monoculture where adventurous-looking courses are actually venturing nothing creatively. It’s difficult to imagine, in that environment, a Jim Engh ever getting another opportunity, or that ambitious, nontraditional artistry such as his could again be enthusiastically supported to any meaningful degree. If that’s the case, it is a darkening on architecture, not enlightenment.

“We should not be turning into automatons.”

That’s not Engh talking, but David Kidd: “There has to be diversity in any creative pursuit, and if you lose that, the creative pursuit dies. The art in it dies. Everyone can’t be the same.”

As different as their approaches are, “I absolutely respect [Engh’s] body of work,” Kidd says. “People love playing his golf courses. His golf courses are still out there. You can’t say to me that, well, he’s no good. His body of work is right there doing just fine. Just because you don’t like it, plenty of other people love it.”

And isn’t that intrinsic to the point of art?

FEELING THE THRILL

Left: Engh, in 2004, at one of his creations, Red Hawk Ridge Golf Course in Castle Rock, Denver, Colorado. i played golf with Engh, once, years ago. It was before the opening of Four Mile Ranch, a course that creeps up and down bare, arid foothills in southern Colorado, and that required almost no earth-moving except in the wildly expressive greens. I brought my father along, and after two holes I could sense his deepening frustration after watching his ball continue to drift off into unfriendly places around the greens.

Engh, a scratch golfer at the time who plays fast and with bravado, noticed as well, and on the third green, a multilevel phantasm saddled between two outcroppings, he intervened as my father was lining up a long, strange putt. “Dick,” he said, “try playing it up over there.” Engh pointed toward an embankment far out to the left. Dubious, my father followed the advice and watched the ball travel up and over a slope, take a hard right turn, circle around and stop 12 inches from the cup.

My father gazed at the ball with something like bewilderment, but from that point on, Engh became his personal caddie, excitedly telling him where to aim drives and on which exotic line to stroke every putt. Dad began to read the course, to see it, and by the end of the round he was playing shots he’d never tried before, never imagined before, firing over rock ledges and bumping putts and chips into the deep funnel shapes and waiting eagerly as the ball rose and fell and swirled and nestled. I remember looking at

Engh, and how he was smiling, proud. As we were walking off the last green, I put my arm around my dad and noticed something else—he was giggling. We were all giggling.