10 minute read

Design Focus

DESIGN FOCUS POWER OF LIGHT

From environmental and organic, to smart and efficient, we look at some of the lighting trends that are making waves in today’s design industry

WORDS BY JUMANA ABDEL-RAZZAQ

The way we live and work today is steadily changing, and with that come changes in the way our spaces are designed. Lighting continues to play a crucial role in this rhetoric, as our past perceptions of space have evolved in light of the unprecedented challenges that we face in our world today. As a result, architects and designers have been instrumental in creating concepts that reflect the changing trends of the design industry at present, while simultaneously looking to the future.

Pando by Mullan Lighting.

Organic forms

Lighting designers are tapping into natural materials to create organic designs that are both environmentally friendly and chic. Mullan Lighting has introduced a striking organic ceramic lighting range, produced by a full-time in-house ceramicist and completely hand-made to order. The Pando stands as the tallest pendant in the collection, boasting a textured, cracked ceramic shade and rugged, aged style. “It truly embraces what clay is,” says ceramicist Stephen Kieran. “We achieve the effect in much the same way the sun dries and crackles earth. The crackle is chaotic.” Italian brand Giopato & Coombes’ Moonstone collection of multifaceted pendant lamps are another example of organic shapes taking prominent space in lighting design. Its biomorphic shapes are inspired by organic rock sculptures, evoking primordial talismans that carry positive energy and ancient wisdom. “Like true amulets, they safeguard us from darkness and release our dreams by subtly bringing the ethereal glow of moonlight into our homes,” the brand explains. Moonstone is carved out of handmade fiberglass and infused with marble powder to create a composite stonelike material protecting its surface and of ‘battuto’ Murano glass or linen glazed diffusers, depending on its size.

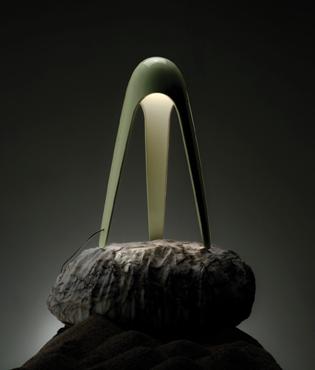

Soliscape by UNStudio for Delta Light.

Health and wellbeing

There has also been significant focus on health and wellbeing over the past years, which has intensified due to the global pandemic. As a result, companies have started looking towards more health-driven solutions. Linea Light Group, for instance, has developed an antibacterial light that protects everyday health using high-intensity narrow-spectrum (HINS) light, dubbed Environment Care Lighting.

“The technology is harmless to people, so it can be used continuously in different spaces, thus improving disinfection and preventing the spread of infection,” says Professor Scott MacGregor, Vice-Principal of the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, who has helped to develop and patent the technology.

Adaptable

User-centric lighting has been proven to considerably boost productivity and wellbeing, says Peter Ameloot, R&D Manager at Delta Light. The company has collaborated with Dutch architecture firm UNStudio to develop Soliscape, a versatile and responsive lighting system intended to create more humancentric spaces that adapt based on users' immediate behaviour and needs. The system can respond, learn and adjust to people's daily activities – taking smart buildings towards responsive architecture. "With the Soliscape system, we have combined two of these facets – sound and light – to create sensory 'interior landscapes' that can support people in their daily activities,” says UNStudio founding partner Ben van Berkel.

3D printing

In recent years, designers have found innovative ways to create durable and functional designs using 3D printing, a sustainable and cost-effective method that marries form, style and practicality. One such concept is Haze, a lanternlike pendant lamp that's wrapped in 3D-printed fabric, conceived by London-based designer Samuel Wilkinson for Swedish brand Zero Lighting. A contemporary take on traditional Chinese lanterns, it features a central globe that has 3D-printed fabric stretched across its exterior.

“The idea arrived by accident after testing some 3D-knitted fabrics [created] for another project on top of a round form in the studio,” Wilkinson says. “By chance, we noticed this hazing effect that happened as the light faded around the form due to the thickness of the fabric.”

Smart solutions

In the face of global challenges like the coronavirus, many designers are looking at smarter and more innovation design solutions that serve a porpose and benefit society as a whole. Urban Sun, a project in development by Studio Roosegaarde, has been designed to disinfect public spaces by shining a large circle of a far-UVC light, removing nearly 99.9% of the coronavirus.

“The power of light can help. Not as a solution to all our problems, but as a first proposal to design our way out of it, to create new, and safer places where we can meet each other,” says Daan Roosegaarde, Founder of Studio Roosegaarde. “If we are not the creators of our future, we are its victims.“

Urban Sun by Studio Roosegaarde.

Digital designs

The advancement of modern fabrication methods has been a leading force in the development of some of the most interesting design concepts around the world today. Designer Karim Rashid's Cyborg table lamp for Italian lighting brand Martinelli Luce is one such concept. A smart lamp with a sinuous silhouette that is said to resemble “a friendly extraterrestrial”, Cyborg responds to human contact through touch-sensitive controls, and comes in both indoor and outdoor versions.

“Only in the digital age do we have new technologies, production processes, materials, software and tools [that allow me to] create sensual and organic shapes, like Cyborg,” says Rashid. id

A new vision

The quintessential Al Huzaifa Furniture explores new horizons of living with the revamp of its Dubai showroom

For five decades, Al Huzaifa has strived to create aspirational living experiences by consistently reframing, redefining and reimagining the way people interact with their homes. Its approach has always prioritised the observation of people's behaviours and emotions to shape its styles and products.

Its recent recalibration is inspired by the deep shifts in the ways people now live, work, play and relax. Al Huzaifa’s belief is that homes must be stimulating yet soothing; energising yet relaxing; familiar and fascinating, all at the same time. Its restaged Umm Hurair showroom responds to just that: juxtaposing styles that play with opposites and effortless elan. The revamped show space provides an immersive experience, where living environments are created with vibrant energy, showcasing a myriad of possibilities and compositions. Featuring the brand’s diverse array of furniture, accessories, lighting, floor coverings, artworks and wallpapers as well as custom fabrication and panelling, the showroom allows visitors to discover the latest collections in an entirely new setting, which is unified in Al Huzaifa’s signature ribbed panelling.

Incorporating muted greys, soft cream and taupe, the collections offer gentle contours and textures across living, dining and bedroom concepts that segue effortlessly from one to the other. The new Al Huzaifa experience is designed to be more than just showroom sets - these are concepts you can take home with you.

BRIGHT LIGHTS

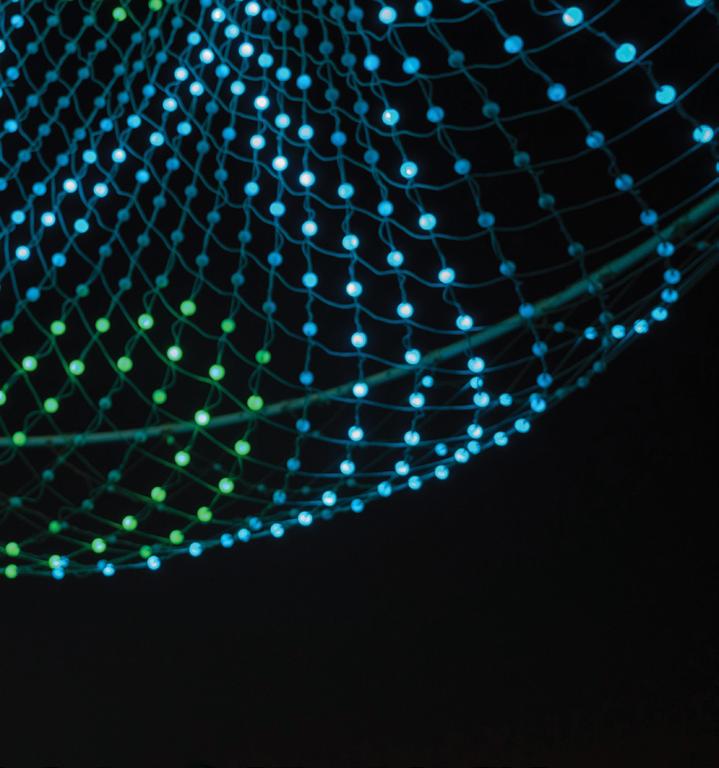

Presented by Riyadh Art and Royal Commission for Riyadh City, Noor Riyadh – the inaugural edition of the annual festival of art and light – is presenting some 60 artworks, including largescale public installations and an exhibition entitled Light Upon Light: Light Art since the 1960s, with the overarching theme of ‘Under One Sky’

WORDS BY RUBA AL-SWEEL

BIG CITY

The sun is not the only source of light illuminating Riyadh’s sky. In the Saudi capital, Noor Riyadh punctuates the ever-sprawling metropolis. The pilot festival is just one of four major projects under the mandate of the Royal Commission for Riyadh City to transform the capital into one of the world’s most liveable, vibrant and sustainable global cities. “Our development plans respect our history and heritage but also look forward to embracing new ideas. It’s the largest investment in public art ever seen,” says architect Khalid Al-Hazzani, Director of Riyadh Art Project.

With this perspective in mind, it’s no wonder that sites like the Al-Turaif historical district – the birthplace of the Kingdom and a UNESCO World Heritage Site – and King Abdulaziz Historical Centre were activated with electrifying large-scale light and music installations that blended seamlessly with the surviving architecture of bygone eras. Atop the National Museum of Saudi Arabia, established in 1999 and designed by Moriyama & Teshima Architects, sits artist Marwah AlMugait’s May We Meet Again (2021), an intimate portrait of people who inhabit this space – mostly migrant workers who frequent the nearby park. The multilingual audio-visual compilation is projected against cascading water in captivating poeticism. Competing for attention is The Cupola (2003) by artists Ilya & Emilia Kabakov. Integrating sculpture, music and colour, the mammoth installation takes inspiration from the cupola of Paris’ Grand-Palais, standing in ceremonial regality in the heart of Riyadh.

Robert Wilson PALACE OF LIGHT, 2021. Aluminium, copper disc, lights, video projection and music. 10000 x 2500 cm. Courtesy the artist. Photo © Riyadh Art.

Ahmad Angawi, ‘Proportion of Light’, 2021. Wood and engraved glass. 230 x 80 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photo © Riyadh Art 2021.

In another part of town, specifically the massive unfurling grounds of the King Abdullah Financial District, artist Daniel Buren has wrapped the ceiling of the Conference Centre with Coloured Triangles by Myriad, for Riyadh (2020-21) and Daniel Canogar jolts the city with electric-like bolts of light zigzagging up and down the Zebra Building. Equally playful with lightning is Saudi artist Ahmed Mater’s Mitochondria: Powerhouses (2021), a collaboration with Madrid-based Factum Arte. A high-voltage Tesla coil sits in a cordoned-off sandpit where flashes of lightning hit the ground in a metaphorical gesture to unearth the forces shaping radical social and urban transformations that define the country.

While dispersed in the urban expanse of the city, the meandering festival is anchored in the landmark retrospective Light Upon Light: Light Art since the 1960s, co-curated by Raneem Farsi and Susan Davidson. “This exhibition gives a historical context to everything you’ll see around Riyadh during the festival. It lays the foundation to the understanding of the Light Art movement and the artists who started it in the ‘60s,” explains Farsi. Taking place at the especially reconstructed King Abdullah Financial District Conference Centre – designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill – some works outshine others. In an ode to the sun, Mohammed Al Faraj’s video installation The Sun, Again (2017) imagines a world in which the sun starts faltering. While the reasons are vaguely communicated, the heavy-duty gas masks and the doomsday ethos indicate a crisis of ecological proportions. In the context of today, perhaps it’s a fable for the accelerationism that blocked the sun. “I’m interested in green architecture and I look at today’s cities with some measure of criticism. It does not take into account natural light as much – I don’t like describing our sun as brutal, it’s generous!” says Al Faraj.

Likewise incorporating architectural elements is Ahmad Angawi, who brings to the fore traditional elements of Hejazi design. In Proportion of Light (2021), he uses 30 sheets of glass on which the pattern developments of the mangour, traditional screens made of wood and prevalent in old Jeddah façades, are engraved. Sitting atop programmed LED lights, the movement alludes to the duality of concealing and revealing as daylight spills into space in varying proportions. “These elements are innovative in how they let light and air into interior spaces. I’m fascinated by how it functions like exhaling and inhaling,” says Angawi. Meanwhile, Manal Al Dowayan lights up a poetic verse by Saudi poet Ghazi Al Gosaibi. Nostalgia Takes Us to Sea but Desire Keeps Us from the Shore (2010) expresses a tension in yearning. “I made this at a time when I was grappling with ideas of belonging – I had just left home and was happy about it but also hated the new place. At the backdrop of all of this is my experiences as a woman, of course,” she tells me. Whether light is used as a material or source of inspiration, it’s clear as broad daylight that Riyadh is having its moment in the sun. id