OFF THE CUFF WITH THE SHOULDER DOC

MISTY MORNING MAPLE

OFF THE CUFF WITH THE SHOULDER DOC

MISTY MORNING MAPLE

A Finger Lakes family and their quiet village brace for the big wind

FREE as the wind

HIGHLAND PIPERS

Important reasons why you should consider Guthrie for your health care needs.

– One of the Top 50 Health Systems in the Nation, Modern Healthcare, 2009.

– Niagara Health Quality Coalition Honor Roll for Excellence in Patient Care (myhealthfinder.com), 6th year.

– VHA Leadership Award for Clinical Excellence, Outstanding Nursing Care, 2008.

– Recognized by the national American Nurses Credentialing Center, as a Magnet™ Hospital for Excellence in Nursing, 2008. Fewer than 5% of hospitals in the nation have earned Magnet Recognition®.

– 100 Top Hospitals in the Nation, 3rd consecutive year.

– 100 Top Cardiovascular Hospitals in the Nation, 6th year.

– Hospitals & Health Networks “Most Wired” Hospital, 3rd year.

We Are Guthrie... & Fitness Center

www.guthrie.org

By Patricia Brown Davis

A Wellsboro tradition since 1935, the Wednesday Morning Musicales sing on.

18

By Tom Murphy

John Elder’s essays in The Frog Run: Words and Wildnerness in the Vermont Woods reveal the bond between stewards of the land past and present.

By Fred Metarko

Our intrepid fisherman learns a new dry land technique—angling for rodents.

22

By Dawn Bilder

Dr. Bradley Giannotti spent his childhood burdened by the limitations of orthopedic medicine, thinking, “There must be a better way.” As an adult, he found one.

24

By John and Lynne Diamond-Nigh

What makes American manners beautiful?

The polite social conformity that, ironically, protects our private lives.

25

By Kathleen Thompson

Priests wear chasubles, doctors wear scrubs, and writers—at least ours—wear ratty sweats and Thor-lo socks.

By Angela Cannon-Crothers

The Yeagers found peace and quiet … and then came the roaring wind.

By Audrey Patterson

In 2001 Wayne and Peggy Clark got themselves into a sticky situation—they started a maple farm. And sweet success has followed.

By Nicole Hagan

English native Pamela Platt has made her life in Galeton, Pennsylvania, restoring America’s handcrafted treasures.

By exceeding national standards, we saved Glenn’s heart and his life.

Life for the Hartzels took a dramatic turn the day Glenn suffered a heart attack. Within fifteen minutes of his wife, Jo’s 911 call, Glenn was on his way to Susquehanna Health’s Heart & Vascular Institute. A medical team was waiting, informed and ready, thanks to advanced technology that sends vital information such as EKG results from ambulance to Emergency Department. Within 60 minutes, Glenn was receiving life-saving treatment. Although the standard set by the American College of Cardiology for improving a patient’s chances of suffering little or no heart damage is 90 minutes, our average treatment time is significantly better at less than 60 minutes. The quick response Glenn received saved his heart and his life.

Life saving emergency care. Life changing people.

“The nurse came in, hugged me, and said everything was going to be okay.”

Jo Hartzel

For more information, visit LifeSavingCare.com

By Roberta McCulloch-Dews

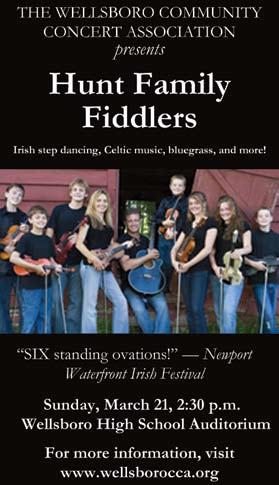

With St. Paddy’s Day nigh, the Penn-York Highlander Pipe Band will be on the march.

Michael Capuzzo

e ditor - in - C hief

By Cornelius O’Donnell

The Naked Chef, Jamie Oliver, makes cooking fresh and easy in his latest book, Jamie’s Food Revolution

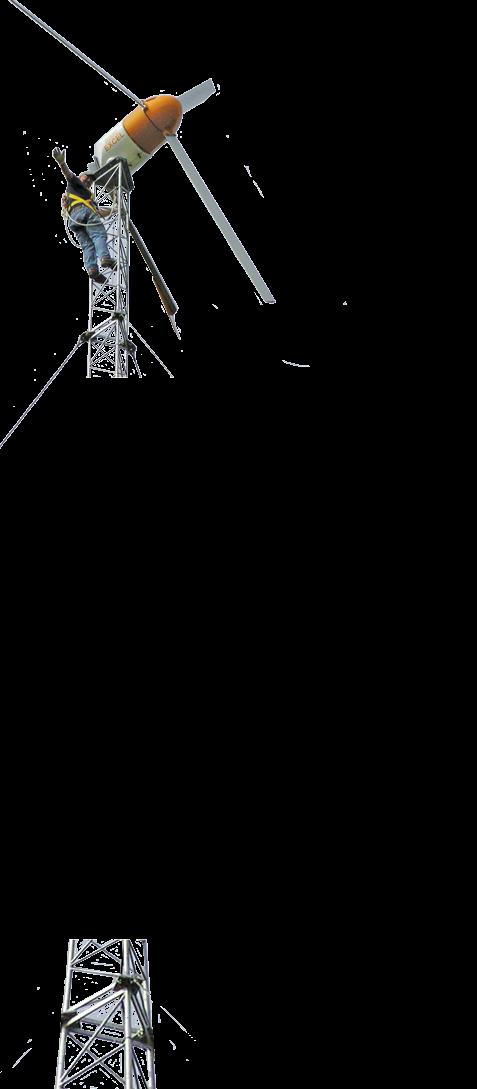

Blowing in the Wind

By Angela Cannon-Crothers

Roy Butler powers his home and his renewable energy business with the winds of upstate New York.

Someplace Like Home

By Dave Milano

Dave explains his world: If you build it … can I help?

Back of the Mountain Spring Returns

Teresa Banik Capuzzo

A sso C A te P ublisher

George Bochetto, Esq.

G ener A l M A n AG er

James Fitzpatrick

M A n AG in G e ditor

Laura Reindl

C o P y e ditors

Mary Nance, Kathleen Torpy

s t A ff W riter

Dawn Bilder

i ntern

Nicole Hagan

C over A rtist

Tucker Worthington

P r odu C tio n M A n AG er /G r AP hi C d esi G ner

Amanda Doan-Butler

G r AP hi C d esi G n A ssist A nt

Kay Barrett

C ontri butin G W riters

Kay Barrett, Dawn Bilder, Sarah Bull, Angela Cannon-Crothers, Jennifer Cline, Matt Connor, Barbara Coyle, John & Lynne Diamond-Nigh, Patricia Brown Davis, Martha Horton, Holly Howell, Rob Lane, Roberta McCulloch-Dews, Cindy Davis Meixel, Fred Metarko, Karen Meyers, Dave Milano, Tom Murphy, Mary Myers, Jim Obleski, Cornelius O’Donnell, Audrey Patterson, Gary Ranck, Kathleen Thompson, Joyce M. Tice, Linda Williams

P hoto G r AP hy

James Fitzpatrick, Ann Kamzelski

s A les r e P resent A tives

Christopher Banik, Michele Duffy, John White

A CC ountin G Zachery Redell

b e AG le Cosmo

Mountain Home is published monthly by Beagle Media LLC, 39 Water St., Wellsboro, Pennsylvania, 16901. Copyright 2009 Beagle Media LLC. All rights reserved.

To advertise, subscribe or provide story ideas phone 570-724-3838 or e-mail info@mountainhomemag.com. Each month copies of Mountain Home are available for free at hundreds of locations in Tioga, Potter, Bradford, Lycoming, Union, Clinton, Wyoming, and Sullivan counties in Pennsylvania; Steuben, Chemung, and Schuyler counties in New York. Visit us at www.mountainhomemag.com.

Get Mountain Home at home. For a one-year subscription to Mountain Home (12 issues), send $24.95, payable to Beagle Media LLC, to 39 Water St., Wellsboro, PA 16901.

LOOK FOR Mountain Home Real Estate Guide wherever Mountain Home magazine is found. P ublisher

If you're looking for a loan, look no further than Citizens & Northern Bank Whether your needs are big or small, we can tailor a loan to suit your household or business. A Home Equity Loan or Line of Credit can help you consolidate high interest debt at a much lower interest rate In the market for a mortgage? We can help with that, too. We will even help you prequalify for a mortgage so you'll know how much house you can afford before you look! We offer car loans, all types of business financing and personal loans for every budget If you're looking for a loan that won't break the bank, see us first. Contact any branch office, call us tollfree or visit us online!

The Yeagers found peace and quiet … and then came the roaring wind.

By Angela Cannon-Crothers

Photography by James Fitzpatrick

Jim and Theresa Yeager were looking for a lovely, quiet place in the country, a peaceful slice of the American dream. Their baby boy Sebastian was sick—sick, they feared, because he was growing up in the urban wasteland of Deptford, New Jersey, a crowded suburb of Philadelphia. He couldn’t sleep, he kept throwing up, his development was lagging.

A growing toddler, Sebastian was struggling “like he was a newborn,” Theresa says. When a medical test revealed high lead in Sebastian’s blood stream, they decided right then to get out of the city and follow their dream to live more naturally.

The pastoral hills of the southern Finger Lakes looked like just the place. In October 2005 the Yeagers and Theresa’s father, Roy Messner, bought 113 acres of rolling land in Prattsburgh (pop. 2,000), a rural village sixty miles south of Rochester, New York. Their dream was an Earthship, a natural and environmentally sustainable home wedged into the hillside as snugly as a Hobbit hole in The Lord of the Rings.

The house, made from recycled materials, would be wrapped into a hillside or bermed with landscape to support heating and cooling, with energy coming from the sun or wind. Rainwater would be for drinking. Wastewater would be recycled in botanical planters. They’d grow food both inside and outside the house.

The first step was building a recycled tireand-earth wrap for the house. They did it by hand and with joy. “We love our mountain,” Theresa says. “We like living in no man’s land.” They loved the pastoral rolling hills and woods, gentle streams, friendly neighbors, the brisk breeze that promised natural wind power. When Sebastian was diagnosed with autism and hypersensitivity to sound—any sound—they were especially thankful for their decision to enfold their house in the embrace of the earth.

“Sebastian can’t handle the sound of a vacuum cleaner,” says Jim Yeager. “He can’t take noises, can’t take even the wind in his ears.”

Then the big wind came. Country wind as loud as a New Jersey expressway began to roar

The sleepy villages of southern New York and northern Pennsylvania are being shaken

by sudden change because of the exploding global demand for affordable energy. Big energy companies from Texas to Boston are puncturing the sky with windmills as tall as the Statue of Liberty to harvest the wind, or plunging pipes into the Earth, miles deep and across, to suck natural gas from the shale. The region is sitting on a Saudi Arabia of gas and oil, folks say. And the wind blowing across the lovely hills is an energy prize, whispering gold, some of the most powerful wind in the East.

The Yeagers had heard there was “wind interest” in Prattsburgh, and being eager to live naturally and “go green,” they thought it sounded like a good idea. They didn’t know that three months before they bought their dream land, local controversy over a proposal to erect ninety wind turbines, each roughly 400 feet tall, in tiny Prattsburgh had landed the village in the New York Times

Local resident Tom Cadigan, 59, who moved to the village with his wife, Kay, to enjoy the peaceful view from their home, told the Times , “My gosh, it looks like there’s going to be five around us. The whole neighborhood could be driven right out.”

The Yeagers had landed right in the middle

of a controversy afflicting many towns around the country as wind farms proliferate. In Prattsburgh and elsewhere the people who would benefit financially from wind farms, including local governments and private leaseholders, often find themselves facing off against neighbors who worry about visual and noise pollution and declining home values. In Prattsburgh, the town and school district point to hundreds of thousands of dollars in revenue from the wind farm. The issues surrounding wind turbines have pitted neighbor against neighbor and even divided some families. Prowind and anti-wind politicians have fought for votes, shaping town elections.

Ironically, the Yeagers were planning to cash in on the wind themselves with a residential wind energy system for home electricity. As the Earthship construction was underway, Theresa’s father built a modest house nearby for himself. Shortly after he moved in, EcoGen and First Wind Inc. began creating gusts of controversy in small towns like Prattsburgh, Cohocton, and Italy—communities of 2,500 residents or less and encompassing approximately fifty square miles. Maps showing the proposed locations for the 400foot wind turbines depict the southern Finger

Lakes region as a pincushion for some 150 industrial windmills.

Although Cohocton residents gave the goahead to wind energy companies, other towns like Prattsburgh and Italy fought to keep their rural settings quiet and unobstructed. In 2007 the Cohocton project was underway with the building of thirty-four Clipper C96 2.5 Megawatt turbines.

The Yeagers’ fears about the location of their home—fit into a south-facing hillside— in close proximity to proposed wind turbine sites made the on-again-off-again progress of their Earthship even more distressing.

“When we first saw on the maps that there would be a turbine up behind our dad’s house we weren’t thrilled, but we thought we could deal. It would be 2,000 feet away from us,” says Theresa. When they discovered that another turbine was slated to be right across the road, less than 800 feet away, they were stunned.

“I asked how I was able to get a building permit if the turbine was going to be so close,” says Jim. “The town supervisor told me he hadn’t known anything about that location when I applied for my building permits.”

Despite his difficulties, at age five son Sebastian is flourishing like never before, and the Yeagers credit the peaceful country lifestyle. Sebastian sleeps now, he hardly throws up anymore, and he’s learning to communicate with some sign language and gestures.

The droning noises that some neighbors hear from wind turbines haven’t reached their home site yet. But although an earth-bermed house will help with some of the noise issues, Theresa says that the

school bus stop will be in “hard hat” zone according to the wind industry’s specifications. Not to mention, their front yard will be too, limiting the play area for all of the children.

“Heck,” cuts in Messner, “if the (proposed) turbine fell over like the one in Fenner, New York, did a couple weeks ago, it would land right on my house.”

The Yeagers fret over complaints from other local residents. Cohocton turbine leaseholder and farmer Hal Graham and his wife, Judy, say they endure sleepless nights and aggravating noise from the turbines.

“They stole our peace with a smile on their faces,” says Judy. Hal has been speaking out about the unexpected noise problems from the newly erected turbines for a year now. The sound has been described as that of a jet engine taking off, an expressway, or the constant drone of a tractor. The Grahams say that leaseholders in Cohocton were told the sound of the turbines was likened to that of a refrigerator running, but that’s not what they hear.

Hal Graham has gone as far as Watertown, New York, seventy miles north of Syracuse, to speak to other communities about the impact of wind turbines. He has officially apologized to his neighbors for the mistake he made in signing a contract with First Wind, a wind energy company located in Boston, Massachusetts. At several of the board meetings in Prattsburgh, Cohocton neighbors have voiced concerns about the noise issues. At one point they were told something was going to be done to solve See Wind on page 16

What? Start your day with live entertainment? Most of us allow ourselves this treat only on evenings or weekends. And what if it was free? Seem unreal? Then unreal it’s been for the past seventy-five years in Wellsboro.

I remember the Wednesday Morning Musicales from my high school days. They’ve had a lasting effect on us lovers of music over the years. As students, we were sometimes invited to perform for them, and they gave awards to outstanding seniors in instrumental and vocal music.

Wanting to share their efforts for the enjoyment of all, they invite the public to attend their monthly gatherings at no charge. Members, however, are asked to pay the minimal yearly dues of $10—which goes toward the high school awards and an honorarium to the professional and amateur musicians who perform each month. Most performances are now held at the Gmeiner Art and Cultural Center during mid-morning and finish well before lunch.

still ongoing Wellsboro Community Concert Association. In addition to the club awards they gave out, some early members also individually supported students like me, giving monetary awards for specific abilities in musical excellence, like my “Mid” Rockwell Outstanding Pianist award. Rosa Hamilton also gave a yearly award to an outstanding vocalist. Later, as a music teacher, I was gratified to present their awards to my own students.

Programs this year included: Mike Galloway and his trumpet students from Mansfield University; Charlie Jacobson singing Lerner & Lowe; Judith Giddings and her Appalachian mountain dulcimer; and Ed Clute, jazz pianist from Watkins Glen. Celia Finestone on harp and keyboard will be coming in April.

This month the Musicales are highlighting their seventy-five-year history. Begun in the fall of 1934 by a group of eight women who performed for each other, it has expanded over the years to include men and those who just want to listen to good music.

Some of us are old enough to remember those original visionaries: Mercedes Dunham, Helen Fink, Lida Green, Rosa Hamilton, Helen Jorgensen, Mildred Rockwell, Rebecca Shove, and Alma Webster. Some of the founders were also instrumental in the organization of the

In honor of this diamond year, remarkable secretarial reports—sometimes highly humorous historical anecdotes—have been shared with the audience, often showing how the Musicales evolved to change with the times. But the original mission of good music and youth support has never wavered. Congratulations, Musicales!

WHAT: Wednesday morning musicales celebrates 75 years

WHEN: march 10, 10:15 a.m.

WHERE: gemeiner art and cultural center, 134 main street, Wellsboro

INFORMATION: for more information, call 570-6595584, e-mail jacobson@epix.net, or pick up a brochure at the gmeiner.

Patricia Brown Davis is a professional musician and memoirist seeking stories about the Wellsboro glass factory. Contact her at patd@mountainhomemag.com.

Easter Sunday, April 4

11:00am-6:00pm

• Fresh Fruit

• Tossed Greens

• Classic Tortellini Salad

• Assorted Dinner Rolls

• Fruit Glazed Baked Ham

• Roasted Leg of Lamb

• Prime Rib

• Baked Salmon

• Scalloped Potatoes

• Roasted Garlic and Cheddar Mashed Potatoes

• Gourmet Macaroni and Cheese

• Green Bean Casserole

• Honey Glazed Baby Carrots & Peas

• Rosted Root Vegetables

Endless

the issue—a spokesman from First Wind suggested that mufflers would be put on the engines.

But Judy Graham says that while two of the nearest turbines have had smaller wings put on to help with the sound issues, “its actually louder. The noise is just terrible.”

Judy and Hal are sixth-generation farmers living in the old farmhouse they restored themselves. “We put a deck out on the back years ago and used to love going out at night and entertaining under the stars or just enjoying the peace and quiet,” says Judy. “We can’t do that anymore.” She also says that she’s been suffering from headaches, their golden retriever barks constantly now, and they often lose their television signal when the turbines turn to face the wind.

And the noise of the wind turbines isn’t the only health concern the Yeagers have. Cases of “flicker-effect”—a flickering of sunlight off of the blades, which is caused by the angle of the sunlight early and late in the day—is said to contribute to migraines. Messner has suffered from migraines in the past but has, thankfully, been able to go off his daily medication since coming to these hills in Prattsburgh, but he’s worried that his migraines will return. “Early morning flicker at the bus stop could also affect Sebastian’s entire day,” adds Jim.

Last November Dr. Nina Pierpont MD PhD published her research on the effects of industrial turbines on human health. The title of the book is Wind Turbine Syndrome: A Report on a Natural Experiment (Santa

Fe, NM: K-Selected Books, 2009). “Wind Turbine Syndrome” is a term she coined to describe the myriad detrimental health effects she discovered in many of her research subjects living in close proximity (1,000 to 2,000 feet) to a turbine. Symptoms include earaches, ear pressure and ringing in the ears, nausea, dizziness, inability to concentrate, headaches, migraines, vision disturbances, inability to sleep, and more.

The Yeagers are emboldened by the fact that the small town of Italy successfully fought against wind farms, but it took them years. The Italy town board has offered Prattsburgh and the citizen group, Advocates for Prattsburgh, their recently written moratorium agreement and wind power industry regulations while Prattsburgh is still in debate.

Although First Wind just recently backed out of its Prattsburg project, another company, EcoGen, is still fighting for its right to build in the village. EcoGen filed suit against the village of Prattsburgh for breach of contract just months after they proposed imminent domain for electric line rights-of-way. EcoGen’s lawsuit against the town for holding up progress on their development has since been rescinded, but the struggle for both sides continues. The energy company’s proposed number of turbines has also dropped from around fifty to sixteen.

Theresa Yeager expressed her concerns for

During World War II, a white peach orchard grew across the road from our house. Today, no sign of it remains. A neighbor told us that when the hundred-year-old sugar maples were planted in front of the house, the farmer’s horses ate the tops off, perhaps explaining the variety of their shapes. Below the barn, cattle were penned, awaiting milking. We planted our asparagus there. Though the gardening books all say asparagus requires extensive fertilizing, we do very little. The manure of those long-gone cows still bears fruit.

I started noticing such hints of the past hidden in the landscape while I was reading the three interconnected essays of John Elder’s The Frog Run: Words and Wildness in the Vermont Woods (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2001). Frog Run is a local phrase associated with maple sugaring: the swelling of the sugar maple buds (when the sap becomes no longer good for syrup) and the spring chorus of frogs begin at about the same time. The last boiling of the sap gathered before both those events takes place, as the peepers sing their mating songs, is called the frog run. Elder uses the seasonal transition embodied in the frog run to describe the transition in his life as his last child goes off to college, as he reflects on his teaching career, and as he begins to work the sugarbush he and his family acquired. Raised in California, he also comes to accept that his life is now inextricably bound up in Vermont.

The book evokes the way the past interweaves with the present. In the first essay, Elder describes that interweaving by referring to another of his interests—the game Go, which he played while he and his family lived in Japan. He uses the term aji. In Go players alternately play black or white stones on a large grid, trying to surround and capture each other’s pieces. Play happens in many places on the board. Sometimes groups of stones will be so surrounded that, while they have not yet been eliminated, they are so isolated that they are essentially dead. But as the game progresses, the situation can change and the

surrounders may become the surrounded. “This surprising potential for apparently dead stones to spring back to life and influence is referred to by Go players as aji, a Japanese word meaning ‘a lingering taste,’” says Elder. He uses the term to describe the relationship between nature and civilization, as in “the surprising reemergence of wilderness from the cutover landscape of Vermont,” or Pennsylvania and New York for that matter. The aji of the wild.

Literature and the natural world are connected in Elder’s life, and in the second essay, he traces his love of both back to Psalm 23: “The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want.” He tells how the balance exhibited in the psalm inspired his love for poetry even as a boy: the walk through the Valley of Death is offset by the presence of the shepherd’s protecting presence; even while the Lord is feasting him, his enemies are present like a lingering taste. He learned from the psalm the beauty of nature, the value of reflection, and the inevitable connection between something and its opposite. The same is true, he says, of another piece of literature he grew to love—Milton’s Paradise Lost: “No Satan, no Christ; no danger, no transfiguration.”

In the third essay we get the story of the building of the sugarhouse, and how, with his two sons, he connects with a now less prevalent tradition of family maple sugaring operations. Elder describes how they bought their 142 acres to practice sustainable forestry and to harvest and boil the maple sap. He discovers, not much to his surprise, that he is building something more as he sees his sons’ commitment to the land and the sugaring grow, as if the aji of that Vermont tradition is binding his own family together.

I was reminded by this book of the many ancestors to whom we are related not just by blood, but also by land. But this is a book rich in connections, and you will surely find your own.

Tom Murphy teaches nature writing at Mansfield University. You can contact him at readingnature@mountainhomemag.com.

On October 5, eight or nine inches of snow fell on Shumway Hill. Branches broke from the trees; the wicked winter was here. I hurried to winterize my boat and put it away for the season. Then the nice weather came, real nice weather—nice enough to go fishing. Bass club members John Tomb and Dan Sauer teamed up to fish the Iron Man Circuit in New York State. They were catching nice smallmouth bass and posting pictures of their catch. It was tempting; I wanted to get my boat out and join the action.

My son Mike and his family were home for Thanksgiving. I was lamenting about the weather and the nice fish being caught. Mike smiled and with a chuckle said, “Dad, I’ve got a great idea for you—why don’t you go chipmunk fishing? You won’t have to get your boat out and there are lots of those little critters running around outside.”

“Chipmunk fishing? What the heck is that?”

“Well,” he said. “Sam (his son) and I were in a gun shop to purchase a shotgun. The guy waiting on us was a real friendly character. We got to discussing the seasons changing from fishing to hunting. He asked, ‘Did you ever go chipmunk fishing?’ We asked what it was, so he gave Sam and me a detailed explanation of the procedure.

‘First you go to the store and buy a bag of fresh peanuts—the ones in the shell. Next pick one of your sturdiest fishing rods and attach a reel spooled with the strongest line you have. Then tie a peanut to the end of the line using the best fishing knot you know how to tie. Put

you’ve seen chipmunks running around. Find a well-used hole in the ground and make yourself comfortable. Slowly drop the peanut down the hole as far as possible. Jiggle it up and down.

‘Soon the chipmunk will smell the peanut and come to get it. When he grabs it, hold on; the fight will begin. He has the nut, it is his, and he is not about to let go. As he heads down the hole it’s time to apply pressure and start reeling. Feeling resistance, the chipmunk will be more determined to keep the nut. The line will tighten and the rod will bend.

‘After a back-and-forth struggle, the chippie is coming your way. You keep cranking as he appears at the opening of the hole. Finally you have him out in the open. He holds firm with all fours planted in the ground, his tail twitching wildly and staring at you with his teeth clenched on his peanut. You get the knife and cut the line. In a flash the chipmunk disappears down the hole with his well-earned nut. After all, bass fishermen do practice catch and release.

‘The fight will be a good one. You land the chipmunk and he is rewarded. You can move on knowing there are a lot more holes and you have a bag full of peanuts.’”

After the story, Sam asked, “Pop, do you think you’ll try chipmunk fishing?”

“No, I don’t think so,” I answered. “I’ll spend the winter getting my gear ready for bass fishing.”

The Lunker is a member of the Tioga County Bass Anglers

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

By Dawn Bilder

While most people are blessed with limber limbs, Bradley Giannotti spent his growing-up years plagued with scoliosis of the spine and forced to wear a back brace in an effort to avoid corrective surgery. The brace didn’t work, and, in his senior year of high school, he endured the surgery and the subsequent three months of bed rest and twelve months in a body cast. As he lay in bed incapacitated and in pain, thinking of all the things he wanted to be doing, all the fun he could be having with friends, a thought recycled itself over and over, one that he would have again as an adult and as a doctor: There has to be a better way

If Giannotti’s body had the first say in his life’s development, he has certainly had the last word. At forty-five, he is an athletic, successful orthopedic surgeon and businessman. He attended George Washington University Medical School in Washington DC and spent his residency at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pennsylvania. This would have been plenty of training to get the job he wanted, but he decided to study for an additional year at the Los Angeles Orthopedic Institute. He is a member of the American College of Surgeons, a fellow of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, and an associate master instructor of the Arthroscopy Association of North America. For twelve years now he’s been with Charles Cole Memorial Hospital’s Champion Orthopedics and Sports Medicine in Coudersport, Pennsylvania. Yet, his demeanor is soft-spoken and humble.

Following his deep-rooted feelings about improving surgery techniques, he decided to revamp the traditional shoulder rotator cuff repair procedure in which surgeons must painstakingly tie sutures in knots to reattach the cuff. He also wanted to find a way to reattach the rotator cuff more securely for his patients. In 2003 he developed his own technique. With his light and boyish sense of humor, Giannotti reveals, “I got the idea when I was driving my garbage to the dump.” He laughs and explains, “I live too far out in the country to get garbage service. The drive to the dump is a quiet time for me to think—a forty-minute round trip.”

Despite its humble beginning, his idea grew to be a nationally recognized rotator cuff repair technique that improves the existing procedure in two ways. “First,” says Giannotti, “it eliminates the need for the surgeon to tie knots because the device has a mechanism that captures the sutures and

ratchets them down. Second, it fixes, or reattaches, the cuff in two points, two areas, as opposed to the traditional one point.” This makes the repair more evenly distributed, and, since the contact area is bigger, it’s more secure. The new technique is also “less invasive, stronger, and takes less time on average. Everybody wins,” says Giannotti.

Along with his older brother, Ron, who sold medical devices, and a bioengineer named Alex Piplani, Giannotti founded the company, Kfx Medical (which stands for knotless fixation) and patented the technique. Dr. Joe Tauro, an orthopedic surgeon in Tom’s River, New Jersey, became a partner when he helped modify the procedure, making it more practical and easier to use.

Giannotti’s technique has been used in over fifteen hundred patients since the FDA approved it three years ago. He tours the country teaching it to other surgeons and receives countless e-mails and phone calls from surgeons thanking him for making the rotator cuff surgery easier on them and on their patients. Giannotti wrote an article about the technique, which will soon appear in the prestigious medical journal Techniques and Orthopedics.

Seven weeks ago Tauro performed the procedure on an interesting patient who loves football—despite being in his forties and never having played the sport in high school or college—who tore his rotator cuff during a game with his friends: Giannotti himself. How did it go? “No surprises, I’m doing fine,” Giannotti smiles.

The only personal items in his office are on the windowsill—a few photos of his twin daughters, Allison and Emily, and his youngest daughter, Natalie. They look to be about nine and six in the prints, but the photographs are old. They are now seventeen and fourteen. Perhaps Giannotti chooses to keep these older photos around because he preferred them at that age, but much more likely it’s because they will always be his little girls. A miniature Everlast desktop punching bag sits by the photos. The last item is a pillow with “DAD” boldly embroidered over the phrases “Strong Shoulders. Saturday Coach. Big Hugs. Fixes Broken Toys and Hearts. Counselor of Wisdom.”

Giannotti’s company is now working on a better way to fix a torn or diseased bicep tendon. It seems clear that this father, surgeon, and businessman will always try to find a better way, and, thanks to his dedication, intelligence, and creativity, he probably will.

Here’s what a prominent Englishman says about us: “In America’s culture, manners are of supreme importance and recognized as the ultimate guarantee of peaceful coexistence. Americans greet their neighbors, speak politely, are always smiling. If someone bumps into them in the street, they apologize; they cannot take leave of anyone, not even a stranger, without wishing him a wonderful day. And courtesy is the ruling principle of business dealings. In short, American manners exist so that people will fit in, not stand out.”

Then, a little mysteriously, he adds this philosophical twist: “The are ways in which individuality is suppressed, and a lingua franca of conformist gestures adopted in its stead. And this has a function, namely to protect the private from the public, to ensure that each person is secure within his space and that the public realm is minimally threatening.”

What is his point? Individualism—isn’t that something in which we take great pride? The title of Roger Scruton’s essay is “The High Cost of Ignoring Beauty.” Americans don’t take beauty as seriously as they do truth or money or family ties, but perhaps, Scruton urges, we should. Then again, such exemplary manners as ours suggest that, in some respects, we do.

The principle of beauty is really a moderating social form of agreement, a code that has evolved over a long period of time by which we behave toward each other as citizen equals. So we should in a democracy. We attended a wedding in Portsmouth, Maine. Old, old houses lined the quaint lanes, some big, some small, but all conformed to a type, a style, a seemliness that kept one from stealing the show or intruding on the other.

Go to a supper party. There may be a banker there, a grocery clerk, a mechanic, a teacher. Look at the table, precisely and beautifully set with china and cutlery, flowers in a vase,

candles gleaming. Does the banker get a bigger plate? No, each place setting is identical. Same goes for conversation at the table. Nothing in our social rules gives the teacher a right to talk louder or longer than anybody else. Every guest, we understand, gets to participate equally.

That’s America. Call that beauty.

We attended a dinner party where an acquaintance brought a new boyfriend. An arrogant and outspoken man, his new Cadillac Escalade was the tiresome (truly tiresome) touchstone of his conversation. The rest of us, we could only infer, with our ordinary cars were little more than pitiable, automotive gnomes. When he left, the word “jerk” floated up like a grateful amen from our mouths. He had offended our Americanness, our manners, our code of fairness and beauty.

But then comes Scruton’s most interesting point: that good manners don’t just flow outward. In fact they protect us.

Many, many years ago, I was taken as a boy with my “peacekeeping” father to a Palestinian refugee camp. We were guided into a low, smoky hovel where the leaders of the camp had gathered. In the dark of night and on the front lines of conflict, I had no doubt they would be lethal adversaries. But in that setting of host and guest, both of our codes of good manners left me completely at ease.

Away from the public sphere, we can retreat into our homes with a calm assurance that we have left no neon sign on our lawn saying, “The jerk lives here; throw firecrackers at will.” If not exactly anonymity, our public grace allows us to slip back into our private world, leaving behind no scent for the curious or the malevolent.

Lynne is an etiquette and protocol consultant and a humanities professor at Elmira College. John is an artist and designer. Please send questions and comments to thebetterworld@mountainhomemag.com.

Kathleen Thompson

Ihave sacred writing pants—pants I only wear when I write. They’re grey Aéropostale sweatpants with a yellow stripe down the leg. They’re about seven years old. They were once my daughter’s and were so ratty even she, of the grunge generation, didn’t pack them when she went to college, so I stole them. They don’t really fit me. I have to roll them at the waist so as not to trip.

Full disclosure: I actually have a sacred writing outfit.

It’s like a uniform for an athlete.

It’s like a bathing suit for a swimmer.

It’s like Carhartts for a mechanic.

It’s like a tool belt for a carpenter.

When I put on these particular clothes, I know that I am ready to head down into the deep recesses of my brain, like a miner looking for gold. It’s dark and dangerous down there, and I won’t be resurfacing for a few hours, so I need to be comfortable. I can’t be distracted by my clothes. They have to be soft, comfortable and not distracting in any

Putting on my Sacred Writing Outfit ritualizes what is a rather mundane, often boring activity. It elevates my writing time into something special, or just something I do consciously.

On the top of these ratty sweatpants, I wear a red, long-sleeved, two-layer cotton tee that is soft and warm. The inside layer is gray, and the outside is red. I’d never wear it out of the house because it looks like I picked it out of the bottom of the hamper (which I didn’t), but I think even if I ironed it, it wouldn’t be presentable for even WalMart or a walk with the dog at night with no moon.

Over that I wear a gaudy, printed, half-zip fleece from REI (also from Emily’s discard pile). Thor-lo socks complete the ensemble. No underwear. Ever.

This is the Sacred Writing Outfit. The writing is not sacred, nor is the outfit. Or maybe both are. It’s the putting on of the outfit that’s sacred. Putting it on signals that writing is going to happen.

It’s like vestments for a priest.

It’s like an apron for a cook.

It’s like a smock for an artist.

It’s like a tie for a banker.

way. Putting on my Sacred Writing Outfit ritualizes what is a rather mundane, often boring activity. It elevates my writing time into something special, or just something I do consciously.

After I finish my writing for the day, I immediately change into different clothes. I never wear my sacred writing clothes outside, ever.

So I ask you: Is there something you do that you’d like to ritualize, make special, set apart in some way? Maybe you could find a hat, a piece of jewelry, a certain pair of shoes, a shirt, a scarf, something you decide you will wear to signal that your special activity is about to begin.

Everyone needs some version of sacred writing pants, don’t you think?

Kathleen Thompson is the owner of Main Street Yoga in Mansfield, PA. Contact her at 570-6605873, online at www.yogamansfield.com, or e-mail yogamama@mountainhomemag.com.

Now at First Heritage Federal Credit Union, you can join for free because we’re waiving the one-time membership fee! That means you get outstanding credit union value for life!

Wellsboro we’re open to the public! That means today and find out more!

By Roberta McCulloch-Dews

George Whyte of Athens, Pennsylvania, recalls when he and a friend first signed on to join the Penn-York Highlander Pipe Band. “I remember an ad in the paper back in 1960. It was on a lark. We saw that they needed members, and I said, ‘Let’s go and join.’”

And so Whyte entered the world of bagpipes, kilts, and tartan plaid, beginning a fifty-year involvement with one of the humanity’s more distinctive musical ensembles.

The two friends went up to the VFW in Sayre, he says. “We filled out an application and joined. All you had to do was sign, and you were in.”

Lucky for Whyte, who’s now the pipe major, the requirements weren’t stringent. “The joke

was the only thing I could play was the radio. But I started to play the tenor drum. My buddy played it, too. Then he dropped out, but I stayed in,” says Whyte, who also happens to be the mayor of Athens.

Since then, Whyte has been a part of the pipe band, also known as the Highlanders, and has loved every minute of the experience. The rules are a little different for members who join today. “Now you have to audition for the instrument that you want to play,” Whyte says. “And there is a commitment that is required when a person signs up.”

The band is comprised of about thirty members. “It’s like a big family. You’ll find that pipe band people are easygoing,” he says. “There’s a nucleus of about twelve to fifteen

players that make the parades in the summer.”

The group holds practices every Thursday night in the Athens Borough Hall. And with its big season kicking off this month—St. Patrick’s Day parades in Binghamton, Scranton, and Wilkes-Barre—the band intends to get in some practices on Sunday, as well.

“There’s a lot of competition in pipe band groups. I would say there are levels of playing ability,” Whyte says. “Grade 1 is the top, and they’re usually from Scotland. We play in Grade 5.”

While this is the rating that Whyte ascribes to the band, the group’s notoriety in the area and their presence at notable events cannot

be understated. “We’ve been leading the St. Patrick’s parade in Scranton every year that they’ve had it. The year that Hillary Clinton was running for president, the crowd was about 300,000,” he said.

Whyte says that this year the band was booked far in advance for certain engagements—a result of the recession, as well as the band’s popularity. “We found that a lot of the committees wanted our commitment early due to the economy. We got requests way back in the fall because they only had a certain amount of money to put into their events,” he says.

Back in 1957 the Highlanders first came together as a group. But before it was a pipe band, some of those involved were once organized in bugle and drum corps. “Back after the Second World War, American Legions all had bugle corps. There was one in Athens that had sixty to seventy members,” says Whyte, of the corps that participated in parades and festivals. “It was an outlet for their social activities; some of the [legion] posts were huge and had become main social

aspects of the community.”

But as times changed, participation in the corps leveled off. “In the early ’60s it kind of dropped off,” he says.

That would have been the end of the band, but someone mentioned transitioning the group into a pipe band. “Other people got involved, and it grew into twenty or thirty people.”

The band then looked for outfits to match their new roles. “The band bought kilts and items that would best be described as from the play Brigadoon,” Whyte jokes. “They got uniforms from a play group in Binghamton, and then sent to Scotland for the bag pipes.”

In the early days of the pipe band, Whyte says the members had to be fast learners of their new instruments and did what they could to adjust. “They started to raise money for the group and as they progressed, they met individuals from other areas who had played for a while,” he says. “Between the ’70s and ’80s, the band finally got formal instruction from a guy in Ithaca.”

The Highlanders have been able to hone their playing skills and maintain the group due to the commitment of the members, and that includes a few young people, as well, Whyte

says. “We just took in a female drummer from Towanda, and she is in high school. The younger kids that do join have a good time.”

Dave Cook is one of those deeply committed members of the band. Cook, who now lives in Romulus, New York, just outside Geneva, isn’t able to make certain events, but he does his best to attend the rest of events.

“My original commute from Ithaca was about one hour, but now my trip is a little less than two hours, or about 100 miles,” says Cook, who joined the band nearly seven years ago. “This commute does preclude me from making some of the early departure bus trips. However, now that I am retired I hope to be able get a hotel room in the Athens area the night before to make these longer trips.”

Plus, there’s one more benefit that Cook derives from the band that makes it worth his time. “There are other bands in Syracuse and Rochester, but they do not do as many events as the Penn-York Highlanders, and I would doubt they are as much fun, anyway.”

Janice

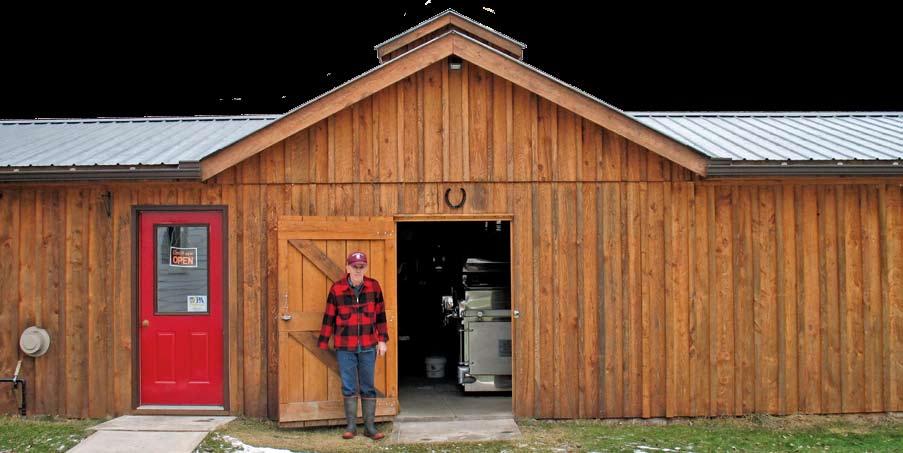

Story and Photography By Audrey Patterson

Sugarmasters take to the woodlots from February through March, creating sweet treats that have been a part of Pennsylvania’s heritage for hundreds of years. Changing seasons are ushered in by the sweet smell of boiling sap and the taste of steaming pancakes drizzled with fresh maple syrup. But for Wayne Clark and his wife, Peggy,—owners of Wellsboro’s Misty Morning Maple—this isn’t a two-month endeavor; it’s a year-round business.

“We used to make maple syrup at home when I was in high school,” says Clark. “I’ve always had an interest in it. After I lost my right hand in 1997, well, I’m always getting into something too far.”

The Clarks started their own maple sugar processing business in 2001. “I was going to an auction sale to look at a bailer, and we ended up over at an open house at Patterson Farms in Sabinsville. Before we left I had bought a 2x6 evaporator and never got to the auction to buy the bailer. When I get into something, I like to learn everything about it that I can.”

When below-freezing spring mornings begin breaking the 32°F mark in the afternoon, the sap begins to flow within veins of the sugar maple

tractor. “It takes me at least two or three hours to gather it all. Then it’s a quick bite to eat and out into the sugarhouse. I have an RO (reverse osmosis) machine that really helps, and with the new evaporator, I’m usually done by midnight or one o’clock. Then I come in, sleep a little bit, and get right back at it the next day.

“It’s still farming,” Clark explains. “The weather’s got to be just right, and you have to be ready when the weather is.”

“We run a fairly modern operation,” says Clark. The RO machine removes the water from the sap. At eight percent concentration, it takes ten gallons of sap to make one gallon of syrup, instead of the usual forty gallons of sap. “And if you only have to boil for two hours instead of eight or ten, you’re burning a lot less wood.”

“We had to build a sugarhouse, so I started with a 14x20 structure. Since then, we’ve added on twice,” he says with a smile. While touring the sugarhouse, Peggy expresses how special it is to them: “The thing about this sugarhouse is that Wayne built it all by himself—after he had lost his hand [after getting it trapped in a piece of farming equipment].”

agrees Clark.

Peggy’s face brightens. “I like to go to shows, meet the people. I really enjoy making the products. Wayne and I make our sugar, cream, and candy together, but the other products I can do myself so he has time to do what he has to do. It works out well. We’re both quite busy with it.”

If you have a sweet tooth, their maple candy can satisfy it. “My idea of candy is like a confection—soft in the center,” says Peggy. She also makes other products with their maple sugar: barbeque sauce, maple mustard, coated nuts, peanut butter maple fudge, cotton candy, maple popcorn, and maple granola.

All the syrup made at Misty Morning Maple—about 300 gallons—is sold at the farm, but since sugar maple trees only grow in the northeastern United States, Quebec, and Ontario, export is a big part of the industry for wholesalers. “Export is increasing by 10% every year,” says Clark. Consumer demand is causing producers to consider changing the syrup grading system. “Implementing this is going to take a long time. I set up a conference call with some of the guys around here, and we talked with the chairmen of the International Maple Syrup Institute. We had our voices heard,” Clark says, satisfied. “It’s a lot of fun to go to these international meetings. You’re right on the

cutting edge of what’s coming.”

When the Clarks aren’t harvesting sap or whipping up sugary concoctions, they’re busy with the Potter-Tioga Maple Producers Association. Peggy leads the advertising, and Clark is a director and a delegate on the board of the North American Maple Syrup Council. Fourteen sugarhouses will be open to the general public during this year’s annual Maple Weekend. “It’s a fun educational process, and it’s really growing,” says Peggy.

When Clark describes his part of the maple process for visitors, his love for the industry and sharing it with others surfaces, infecting those with whom he talks. “When they come and talk to Wayne, they’re so enthused,” says Peggy. “We’ve met a lot of nice people since we’ve been doing maple.”

“The maple industry has that draw, that romance to it,” Wayne agrees. “It’s a spring ritual.” He sits back in his chair. “The maple world is kind of fun.”

WHAT: potter-tioga maple producers association maple Weekend

WHEN: march 28–29

INFORMATION: for a list of participating maple farms, visit www.pamaple.com.

Naturalist and author Audrey Patterson is a firsttime contributor to Mountain Home magazine.

Cornelius O’Donnell

In many ways I wish I had had television personality Jamie Oliver’s new book, Jamie’s Food Revolution (Hyperion, $35), when I was starting to cook. Subtitled “Rediscover how to cook simple, delicious, affordable meals,” it is equally helpful for those just beginning to try their wings in the kitchen, although you’ll have to get the recipe for the Buffalo variety elsewhere. This is a British book, and you have to allow for things like cress, kettle, Fish Pie, and other references. Be brave; it’s easy, and you’ll figure it out in.

Oliver became a young superstar thanks to the Naked Chef moniker and his breezy style. His last few books—Jamie’s Food Revolution is his eighth—didn’t simply give recipes. The tousled-haired lad now exhibits his social conscience. Among other things, he’s helped

Preheat your oven to 400°F. Get yourself 1 3/4 pounds of LEEKS. Peel back the scruffy outer leaves, trim the ends and discard, then quarter the leeks lengthways and roughly chop them. Put them in a colander; give them a really good wash to get rid of any dirt, and drain. Peel and finely slice 2 cloves of GARLIC. Put a large pan on medium heat and add 2 pats of BUTTER, a lug of OLIVE OIL, and the garlic. Pick the leaves off 6 sprigs of FRESH THYME, discarding the stalks. Just as the garlic begins to take on the smallest amount of color, add all the leeks and the thyme leaves and give them a stir.

Turn up the heat and cook for about 10 minutes, until the leeks have softened. Meanwhile, grate 1 cup of CHEDDAR CHEESE. Remove the pan from the heat and season with a couple of good pinches of SALT AND PEPPER. Add just under 1 cup of HEAVY CREAM and half the grated cheese. Mix everything up and transfer into a baking dish that will give you a layer of leeks about 1 inch thick. Sprinkle over the rest of the cheese and bake in the preheated oven for about 20 minutes, until golden and bubbling. (Note from Cornelius: use about 2 Tbs. each of the oil and butter.)

disadvantaged youths find careers in food service. And you might have caught his television series about raising food at home and cooking it within seconds of harvesting it. It, too, spawned a book.

In the newest book, he aims to get the reader to make one recipe from each section and then pass it along to a friend who is expected to do the same. Don’t worry about all that—though it is a nice idea. Instead, look at the splendid color photographs, some step-by-step, that practically guarantee perfect results.

A word of caution, however: Many of the recipes are geared for two, especially in the “Twenty-minute Meals” chapter that begins the book. Once into each section, the offerings yield the usual four to six servings. And not all the recipes are in the usual form with ingredients listed separately. The vegetable chapter is an example, and you’ll find a recipe in that style in the leek dish that follows.

If you’ve traveled to England, surely you remember the many Indian restaurants. This book reflects that influence with many curries. To get you hooked, try the Chicken Korma, a mild and creamy version that even kids will enjoy. There are color photos to help you get it right.

If you’ve shied away from salads and stuck with iceberg lettuce and bottled dressing, you’ll find the salad section particularly inspiring. He makes his dressings in jam jars

(so do I), and his approach to what goes into a salad is particularly useful. He calls this “the philosophy of a great salad, pick-and-mix style.” And there is a series of twenty-six photos scattered among sections: soft and crunchy greens, herbs, veggies, cheese, and toppings. Pick one of each category and toss.

I loved the “Homely Ground Beef” chapter, which includes (his titles): A Cracking Burger, Good Old Chili Con Carne, Ground Beef Wellington, Pot-Roast Meatloaf, Bolognese Sauce, etc. His Tomato Spaghetti is simplicity itself. Is this accessible food? You bet.

This is certainly a “different” kind of cookbook, but it’s warmed by Jamie’s approach to cooking. One repeated instruction: “Add a good lug of olive oil.” (I figure it’s two tablespoons.) Another: “Give the pot a little love and attention, and you’ll be laughing.” This just might be England’s answer to “BAM!”

Now if Jamie would only comb his hair!

By Angela Cannon-Crothers

oy Butler is a wind-power expert who practices what he preaches. He lives off the grid with a small wind turbine and solar photovoltaic (PV) system, proudly helping his budget and the environment—and living with the consequences.

When the wind blows, he’s right there to catch it. When it’s calm, he catches grief from his children, especially when their bedrooms go without electricity—which doesn’t happen as often now that he has a solar PV array to rely on.

“I don’t recommend that for everyone,” he says with a grin. Most of his clients like electricity in their bedrooms at all times—and Butler happily supplies it with wind power.

Butler operates Four Winds Renewable Energy in Arkport, New York, a business that got off to a steady spin in 1997. Butler, who has been promoting and installing renewable energy systems for more than seventeen years, is a nationally requested speaker on wind and solar electric systems. He teaches training courses for the Mohawk Valley Community College in Utica, New York, and Alfred School of Technology in Wellsville, New York. He also serves as a technical editor for Home Power magazine.

Back when he first got into renewable energy, the family electric bills were topping $400 a month, so he and his wife, Carol, put up their own wind turbine and disconnected entirely from the grid. They knew the system was too small to meet their needs, but they planned to install additional capacity as they could afford it.

“We went cold turkey,” laughs his wife. “The kids were so mad.”

One of the first things the family learned was that in order to meet their energy needs entirely with one small residential turbine, they were going to have to greatly downsize their energy use. No more old energy-sucking refrigerator and doing

the wash on non-windy days.

“We don’t recommend doing it this way for just anyone,” says Butler. “Most residential wind electric systems are on-grid and utility interactive so you don’t use a battery bank to store your power, and you don’t have to worry about using electricity when the wind’s not blowing.”

Butler says there are two basic types of wind electric system buyers out there today: those who want to reduce their consumption and impact on the environment and “a whole new generation of buyers who put up renewable energy systems as part of their home improvement.” Many states now have incentive programs that help reduce the cost of installing wind or solar PV systems. Pennsylvania has the Sunshine Program solar PV and solar thermal systems. New York has the NYSERDA solar PV and wind incentive program. These incentives, together with state and federal tax credits, go a long way toward making renewable energy systems more affordable than they have ever been.

“One of the other great incentives for putting in wind (if you have a windy site) or photovoltaic systems, is that you end up locking in your energy costs with today’s dollar value, providing a hedge against inflation,” says Butler. “Because you’re connected to the grid and essentially making energy for others during over-peak production times, when the utility company rates go up, the value of your energy production does, too.”

Getting a system put in at your home or office takes some study and a lot of paperwork, but it’s worth it. “I have a customer who was homeschooling their kids, and we estimated that a renewable energy system would cut 68% off their projected electric bill. They were so excited when their savings ended up being closer to 75%, that the kids got involved in researching how to cut it back even more with conservation measures. Right

now they have their electric needs down to only 7–8% grid use, and they are hoping to get to zero.”

Butler has had an interest in alternative energy since boyhood. Back in 1968, when he was just thirteen years old, he designed and built his own AM radio for broadcasting. But the remote location where he kept his radio station hidden was requiring more batteries than a young teen could afford. So Butler rigged up a solar power system for his radio. In high school he got into alternative fuel generation by powering an old Briggs and Stratton engine off methane made from school lunch leftovers, which, he says, “was easier to come by than manure—at least until the lunch ladies found out what I was doing and wouldn’t give me any more seconds.”

Carol and Butler use, install, and promote small wind turbines of 100 kilowatts or less, but they’ve had their share of fallout from people opposed to industrial turbines. “People see our Four Winds Renewable energy sign on the truck and want to express themselves,” says Carol. “Sometimes, even after we tell them that that’s not what we do, they still keep going on.”

But the Butlers aren’t opposed to the industrial turbines topping many of the hilltops in the area. Butler sees that America’s energy solution will require a mix of options from wind and solar to natural gas and coal—even nuclear energy.

“We need to intensely research our alternatives,” says Butler. The first thing he believes anyone can do, right now, is to simply practice energy conservation. “Conservation has immediate benefits,” says Butler. “And conserving energy doesn’t cost you anything,” adds Carol. Butler nods, “Of course, I also love the fact that renewable energy is good for the environment.”

Angela Cannon-Crothers is a freelance writer and outdoor educator living in the Finger Lakes region of New York.

Dave Milano

The Urge To Build (UTB) has been infecting men for as long as anthropologists can tell and probably way before that. It was men who built the pyramids, the Roman aqueducts, and the Great Wall; men who assembled Stonehenge, carved the monuments of Easter Island, and erected every backyard shed from Greece to Grand Rapids. Women, on the other hand, didn’t.

UTB is a virtual epidemic in men, while women seem to enjoy near perfect immunity from it (unless you count the urge to rearrange the furniture, or repaint the bathroom, or make frowny faces at the new kitchen plan). Even today, smack in the middle of the gender uniformity era, most architects and builders are men, and it’s generally men who discover when an architect or builder is needed. That’s just the way it is.

I’ve been a builder since I was two or three years old. Back then, sand piles and sticks and wooden blocks were my concrete and steel, calling to me, begging to become something else—usually something bigger. I built splendid, happy piles of mud and detritus that were houses and forts and roads, then demolished them to make room for more. Not much has changed since then. The unassembled still compels; entropy continues to annoy.

Fortunately for men, there is never a shortage of good reasons to build. Unsheltered animals and machinery, a tree without a house, previous projects needing revision, and two-hundredpound rocks in stump holes seem to just appear out of nowhere. (That last might easily have been dragged into the woods, but ended up tilted against a tree in the yard, a fractional building project obviously being better than none at all.)

For me, building with stone soothes UTB symptoms like nothing else, probably because stone is such an elemental building material

(not unlike sand and sticks and wooden blocks) and because the tools used to work it— hammer, chisel, and pry bar—are pleasantly austere and sober.

That’s about the only explanation I can offer for our henhouse steps, which are made of fieldstone hand-picked from our woods, laid dry for that natural, last-a-lifetime effect. Wife Mary, apparently feeling that this particular project required closer-than-usual supervision, donated a full day to help build them. Afterward, obviously impressed with the stout, snug laminations, she asked, “How much stone is here?”

“I don’t know, exactly,” I answered. “Probably a ton and a half. Could be more.”

“Hmm.” She squinted. “Why is it that our front steps are not nearly as nice as our chickens’ steps?”

“Oh, because, well … hey, wait! There’s a great idea! We could bust out our front steps and build new stone ones. We’d have to lay in a gravel bed with perforated pipe connected to the foundation drains, of course, and extend out for a new landing, but that’s no big deal. And that stone leaning there against the tree would make a perfect start. You busy tomorrow?”

“You’re on your own bucko,” she said. “I’m rearranging the furniture.”

Dave Milano is a former suburbanite turned parttime Tioga County farmer. You can contact him at someplacelikehome@mountainhomemag.com.

Kirby

By Nicole Hagan

Pamela Platt, owner of Bittersweet Antiques on Route 6 in Galeton, understands this remark all too well. Her shop of pre-1900 American furniture is a collection of old memories—both personal and historical. While the name of her shop in part originates from the native wild bittersweet vines, Platt also realizes that her antiques are a nostalgic remembrance of the good things past that are still cherished and enjoyed today.

country lighting—the 100-year-old primitives, or hand-made furniture that “the settlers made themselves,” according to Platt.

The search for these antiques is what keeps Platt going, even at the age of eighty-six. “Hunting for antiques gets in your blood, and you just can’t give it up,” she says.

Over the years, she has come across painted high-back dry sinks, desks that come in plantation styles, pewter cupboards in their original paint, and even an 1825 Sheraton chest—one of the oldest antiques she’s ever found.

Shop: Bittersweet Antiques

Owners: Pamela Platt

Address: 793 Route 6, Galeton, PA

Phone: 814-435-9916

From the first moment that Platt went to an antiques auction over thirty years ago, she was captivated by the charm of old American furniture (ironic, considering she’s originally from Addiscombe, England). “I think my shop has been successful because the younger generations are finally growing to appreciate their grandmas’ furniture,” Platt explains. “When they were younger, they didn’t take notice of it, but now they look at the new stuff and see that it has plywood backing and realize how nice the older furniture actually was.”

Hours: Saturday & Sunday, 9 a.m.–6 p.m. (and by chance or appointment during the week)

And when she finds a piece that isn’t in selling condition—a cupboard speckled with watermarks or a desk that needs a new finish—Platt knows how to soften the bitter marks of maltreatment.

“I’ll take the varnish off, but I never sand it,” Platt says. “Then I’ll use early-American stains to give a honey color to the pine and finish things up with tongue oil to give it a nice soft finish.”

Her love for antiques—old and abandoned furniture that just needs a little care—quickly turned into a profession as she began selling antiques from her garage. But Platt soon found the need for more space as the the pile-up of furniture spilled into her home.

“I needed my house back,” Platt jokes. “I had furniture all over the place, and I needed another space for my business.” To solve the problem, Platt built a carriage house on her property in the spring of 1980. Today Platt’s clients come to the carriage house for her collection of dry sinks, pie safes, cupboards, cherry chests, desks, and early

Much like the old American craftsmen who first created it, it’s a style and a personal touch that she’s developed through time, and Platt agrees that it’s the individuality of each piece that makes every pie safe, step stool, and dry sink unique.

Platt’s antique shop will reopen its doors for the season in March, but it will only remain open until the property is sold. Platt put her home and the carriage house up for sale, and, as a result, this may be its last year in business. So if you’re looking for hand-crafted furniture that’s stood the bitter test of time, make your way to Bittersweet Antiques.

A Downtown Shopping Tradition Since 1946

Exquisite Gifts

Exceptional Greeting Cards

Green Mountain Coffee FedEx / UPS Worldwide Shipping

Monday thru Saturday: 8 a.m. - 6 p.m. Sunday: 9 a.m. - 3 p.m.

(607) 732-1152

her autistic son and her family to EcoGen representatives after she was told by a sound engineer for the town of Prattsburgh that she should move the house.

The energy company was not deaf to her needs, she says. Tom Hagner of EcoGen heard the Yeager’s concerns, and, according to Theresa, began “looking into moving back some of the proposed turbines.” But Theresa was told by her son’s occupational therapists at school that the relocation of the turbines would still be too close for Sebastian.

They’ve already moved the Earthship once—by hand—and can’t do it again. “We can’t move the Earthship back any farther. There’s a pond too close, and Sebastian has no fear or understanding of the danger of falling in.”

“In this environment—without the noise, the lights, and constant distractions—Sebastian is developing and,” Theresa adds emphatically, “he’s sleeping!” She smiles a moment and then says, “we’re doing the same things for Sebastian here as we were doing in New Jersey, so if it had nothing to do with the environment, then why is he having such major progress now?”

“The setbacks [the distance the turbine must be from residential areas] of these structures aren’t enough.” worries Theresa. “In other countries, which have been putting up turbines for more years than we have, they’re finding that their setbacks aren’t far enough.” Dr. Pierpont recommends setbacks of at least 1.5 miles from human habitation.

For now, the Yeagers are hoping that town officials will vote for a moratorium on building and that EcoGen will fix the location of many of their proposed turbines in Prattsburgh. At a public hearing on February 15, there was strong support for a moratorium on EcoGen’s turbines at the town meeting, but the final vote has been stayed until next month, at the earliest. Jim says, “We’ll keep building our house this summer and hope they realize that building turbines that close to a home is ridiculous.”

Prattsburgh town councilwoman, Anneka Raiden-Snaith, says she would tell other communities considering wind turbines on their hilltops that “there’s a lot to consider, but, most importantly, because noise and vibration issues haven’t been fully resolved,” she says “regulations must reflect adequate setbacks from residences and property lines.”

“We’re hoping that the town will set up good laws to keep people safe.” adds Theresa. “It’s just that the laws haven’t caught up to the technology yet.”

Those in support of the wind turbines hang signs that say, “We support clean, renewable, energy.” Opponents argue—who doesn’t? But for them, while energy consumption and solutions are environmental, they are a people issue first and foremost.

Meanwhile, Theresa and Jim Yeager keep building their dream house, the Earthship, hoping the windmills won’t come too close, or be too loud, but mostly waiting out forces beyond their control—waiting to see which way the wind blows.

o er Saturday hours from 8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. for ALL Laurel Health Center

if you aren't normally seen in the Wellsboro o ce!

You don't have to see a pediatrician to obtain proper treatment for your child—our Family Medicine specialists are highly quali ed to treat patients of all ages, from children to senior citizens! In addition to routine care, we o er the following services for pediatric patients: