8 minute read

ARTS & CULTURE |10-11 | A podium for change

3 Cincinnati conductors share perspectives on race, culture and choral music

By David Lyman

Advertisement

As a freelancer, when an editor calls, my default response is “yes.” Always. It rarely matters how much I like the story or the subject or the issues involved. It’s always “yes.”

But when this story was suggested to me, I had to think about it a little more.

I liked the subjects a lot: Jillian Harrison-Jones is the music director of MUSE: Cincinnati Women’s Choir; Steve Milloy is artistic director of Cincinnati Men’s Chorus; and Jason Alexander Holmes is artistic director of Cincinnati Boychoir.

But to my eyes, the primary connection among the three was their race. Yes, they are all choral conductors. And all are relatively new at the helms of their respective organizations, though as he closes in on three years, Milloy can hardly be considered a newcomer.

Obviously, I agreed to do the story. But I still felt awkward about it. I mean, would I be writing this story if all three conductors were white?

So as I sat down with the three subjects at A Taste of Belgium at The Banks, I told them of my qualms. They understood. They are weary of being referred to as “black conductors.” But they are pragmatists. Race, they have come to understand, is simply one more bump they have to navigate in the professional landscape.

“I’m a bit older than these other two,” said Milloy, “so I’ve had to deal with a few more issues.” Clearly, he is eager to get into the thick of it.

A matter of ‘Pride’

He recounted his June 2017 “audition concert” with CMC. Named “Pride,” it was a preview to the chorus’ Pride Week activities. The concert’s promotional graphic featured a “Lion King” sort of lion head and then the word “Pride” in cartoonish lettering meant to look African.

“If that wasn’t bad enough, one of the songs they wanted to do was Toto’s ‘Africa’,” Milloy said.

“Let the record show my face,” Holmes chimed in, grimacing at the memory of the catchy 1980s anthem that had nothing to do with Africa.

Now, Toto wasn’t a musical hill to die on. But Milloy steered the group away from the selection, suggesting that they ditch the logo and create a concert about “intersectionality, about AfricanAmerican music and how it intersects with the gay community.”

Milloy also added to the concert Joel Thompson’s “Seven Last Words of the Unarmed,” a sevenmovement work, each quoting the last words of an unarmed black man before he was killed.

Milloy was named artistic director a month later. Harrison-Jones and Holmes have similar stories to tell, mixing triumphs and frustrations. Some have been contentious and left permanent resentment. Others have been resolved by judicious compromise, like the time Harrison-Jones conducted Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddam” on a MUSE concert.

A handful of choir members balked at the song. Was it because of the language? Certainly. Was it further complicated because those singers – most were white – didn’t fully grasp the underlying rage of the song, which was composed in the wake of murders of black Americans during the early 1960s civil rights movement? Perhaps. It’s hard to say. Harrison-Jones felt strongly about the song. But she knew that doing battle with chorus members was not the way MUSE does business.

In the end, the objecting singers stepped off the risers and remained on the side until the song was completed. It was an awkward compromise. But MUSE is an organization devoted to all members having an equal voice. So the resolution fit the mission.

Steve Milloy, artistic director of Cincinnati Men’s Chorus; Jillian Harrison-Jones, music director of MUSE: Cincinnati Women’s Choir; and Jason Alexander Holmes, artistic director of Cincinnati Boychoir

Respecting the cultural context

Even though none of these music directors leads an Afrocentric music organization, it is inevitable that they are looked on as standard bearers for their race. They become the arbiters of all things black. And, in some ways, they are. “Every piece of music has a cultural context,” said Holmes. “And no matter what the roots of that piece of music are, you need to research it and respect it. I have heard music from ‘my side of the tracks’ completely butchered by people who didn’t bother to do their research. They would research Mozart or any other ‘serious’ music. But they think they can just scream a spiritual at the end of a concert. That’s not OK with me.”

“That’s my criticism of lots of Master’s and DMA (doctor of musical arts) programs,” said HarrisonJones. “They don’t teach ‘other’ music there. That was one of my biggest criticisms – even at CCM, as amazing an institution as it is – the only exposure I got to African-American music was what I brought to the class.”

Milloy recounted an episode when he led one of CCM’s elite choruses in a performance of Richard Smallwood’s “Total Praise.” It is an iconic 1996 song that has become a much-loved staple in black churches and choirs. But it is much less known to the primarily white academic music world.

Soon after the performance, he got a call from the group’s music director wanting to know where they could order the music.

Milloy’s facial expression as he told the story said it all. The music director should have known. This is a significant piece of choral music. It has been recorded scores of times. But because it was from the genre of African-American gospel music it was largely invisible in the academic world.

So is there still a racial divide? Of course. It’s not necessarily antagonistic. But it is a reminder of how timely Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel “Invisible Man” remains today. If you or, in this case, your music is not of the majority culture, it must not be important. Oh, it’s different with pop music. Or rap. Those are “lesser” musical forms. But to enter the vaunted halls of concert music or serious vocal music? There seems to be a different standard.

But it’s one that these three musicians are determined to keep challenging.

A lack of representation

Milloy noted that what drew him to Cincinnati in the first place was his experience at a GALA Festival 20 years ago. (GALA is the Gay and Lesbian Association of Choruses.) He was shocked at the lack of minority representation in choruses from supposedly sophisticated communities like New York and Seattle and San Francisco.

“Then I see a little city like Cincinnati and there are 50-60 guys up there and there are like 6 black guys, two Asians or Pacific Islanders,” Milloy said. “I was like, ‘What the heck. What’s in the water in Cincinnati?’ ”

Holmes remembered being challenged by his Boston friends when he said he was considering a move to Cincinnati. “But when I first moved here, I was making all the rounds, meeting all the people I could,” said Holmes. “I made a point of meeting with Evans (Mirageas) from the opera. And he could speak with detail about the community engagement process. And I was . . .” Again, he let his face do the talking, showing how floored he was with the depth of Mirageas’ knowledge.

“I can tell you – that usually doesn’t happen. They usually say ‘We do some community work’ and then give you a few bullet points. But he was giving details – with passion – about what was going on. It was impressive. And, I think, they’re living up to it.”

Holmes knows he’s not intimate with the community yet. He just arrived last summer. Besides, he doesn’t want to sound too Pollyannaish. He’s not about to lead the Cincinnati Boychoir through a musical revolution. But he wants to nudge the group forward and broaden its musical understanding, just as Milloy and Harrison-Jones want to do with their groups.

“I would like to see us respect and value a variety of music with the same zeal that we do with ‘Panis Angelicus’ (César Franck), which is gorgeous and really does sound beautiful with their voices. But there is other music that is just as beautiful and deserves the same kind of respect.”

He recounted a recent trip to Nashville by the Boychoir’s intermediate ensembles. They sang at a church and led a workshop. They also visited Studio B, birthplace of the Nashville Sound, and recorded a song at the Country Music Hall of Fame.

“These were experiences that were held with the same value and the boys had a great time with all of it. And they shone,” Holmes said. “I’d like to see that across our organization. And I’m working to get it that way. The beautiful thing about being Americans is that we do have a whole lot of stories to tell with our music.”

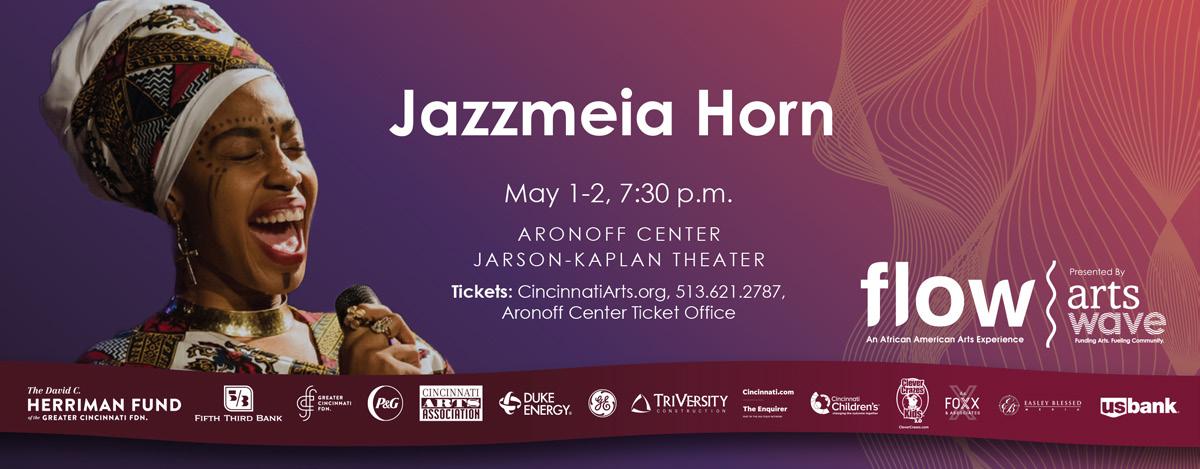

Advertisement (Please note: this performance will be rescheduled to a later date)

About the conductors

Jillian Harrison-Jones became music director of MUSE: Cincinnati Women’s Choir in 2018. A native of Rochester, N.Y., she is working toward a doctorate in choral conducting at the University of Cincinnati’s College-Conservatory of Music, where she is also the assistant director of the Cincinnati Children’s Choir. She has guest conducted widely with choirs and orchestras, and continues a schedule of choral and conducting seminars throughout the country.

Jason Alexander Holmes was named the sixth artistic director of the Cincinnati Boychoir in July 2019. Prior to coming to Cincinnati, the Virginia native was associate director of choirs with the Boston Children’s Chorus. He has been on the faculty at the Rochester School of the Arts, the Finger Lakes Opera and the Geva Theatre Summer Academy in Rochester. Since coming to Cincinnati, he has continued to teach privately.

Steve Milloy assumed the artistic directorship of the Cincinnati Men’s Chorus in July 2017. Milloy was already wellknown to the chorus, having composed, arranged and guest-conducted for the chorus since 2001. He is a tireless arranger of music for choruses, as well as an occasional music director for musical theater. Among his many notable compositions is an oratorio “Bayard Rustin: The Man Behind the Dream,” premiered in 2018.