MovingMagazineMetal

Moving Metal Magazine is a bimonthly electronic magazine designed to offer content for beginner, intermediate and experienced blacksmiths; and, to join together a worldwide group of craftspeople. We will feature the smiths you know and some you may not. In addition to these features, we will publish news, articles and features about events, associations, how-tos, and a wide variety of information.

Moving Metal seeks to support the community of blacksmiths worldwide who are keeping and growing a craft that is one of human society’s earliest occupations. Editorial and promotional content will entertain, inform, educate and promote on behalf of this community.

Looking to be good stewards of the planet, Moving Metal will be published in electronic form only. That also means you can take it with you on your mobile device wherever you go.

Content submissions are welcome with the right of final editing for style, tone, voice and length by the Moving Metal team. Editorial and graphic content contained in each issue may not be used in any form, printed or digital, without the permission of the editor and only with attribution.

Editor:

Dan Grubbs

Contact:

Moving Metal Magazine

13605 Jesse James Farm Rd. Kearney, Missouri 64060 USA

816-729-4422

movingmetalmagazine@gmail.com

MeWe

Forged In Fire champion Billy Salyers gives us good news about a forging program for veterans and first responders. page 6

Caleb Kullman relates why a design process is an important part of his blacksmithing whether a piece of art or architecture. page 18

Marrying two art forms, husband and wife, Johanna Willsey and Kyle Lucia collaborate to create beauty and grace. page 38

Jennifer Lyddane, the Lipstick Blacksmith, shares her insights into her experience as a multi-episode contestant and Forged in Fire champion. page 46

From the Editor

Here it is already past time for our second issue. Life throws us challenges and we must overcome them and so here is what I believe to be an issue well worth the wait.

There was plenty of positive response to the first issue and I want to thank all those who shared encouragement and kind words. I also want to thank those who reshared our publication in their social media accounts. That is the secret to helping our community strengthen and grow. The more we all personally connect and share, the more we will all learn and be better what we do.

I didn’t plan that our first two cover features were going to be European blacksmiths, but that’s what happened. This issue we feature Oscar Duck, a young smith from England who is as affable as he is creative. His art pieces are beautiful and his story from going from part-time apprentice to full on blacksmith is a good one.

Billy Salyers writes about how blacksmithing can be therapeutic for many who are struggling with issues, such as PTSD. He shares a great story about Reforged, a peer support group for veterans and first responders. Teaching veterans about bladesmithing also helps to create a network of support and new friends for those who may need it most.

Next, a very talented smith, Caleb Kullman out of Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA, reveals a bit about his creative process and how he approaches design for his art and architectural blacksmithing. Formally trained in art school, Kullman’s work is inspiring.

Speaking of art, what if a married couple who practice two different forms of visual art decided to blend their crafts? Look no further than Johannah Willsey and Kyle Lucia of Phoenix Handcraft who create some beautiful and artistic work in collaboration. Joining blacksmithing and mosaics, their work may grace your wall or your garden. Does art imitate life? Possibly, if you’re looking at

the animal figure heads of Kees Klaassen of The Netherlands. His how-to article on forging realistic animal heads shows that his approach is as unique as it is effective.

No one likes to fail. But Joshua Frost, another great Forged in Fire champion, teaches us that Thomas Edison was right in the idea that failure is an important part of our craft as blacksmiths. He writes that “one of the most important steps in the learning process is failure.”

Speaking of Forged in Fire, I interview Jennifer Lyddane, who has now become known as the Lipstick Blacksmith after two appearances in the show. Though she was eliminated in her first appearance, she redeemed herself later after being named champion following the second-chance tournament in 2020 that aired in 2021. She gives a bit of behind-the-curtain look of what it’s like to be a contestant on the popular History Channel show. Check out how this barber-turned-blacksmith who “just likes to play with fire.”

Be sure to check out the videos I’ve uncovered in the regular piece titled, “In Case You Missed It.”

In case missedyou it

Forging a boarding pike

Each issue, Moving Metal Magazine will present six videos that have something of interest for readers that likely have slipped under most people’s radar. If you know of a video others may have not seen and you think is worthy to share, be sure to let us know.

Designing and forging a gate

Forging and mounting a spear head

Forging a campfire grill

Forging a shoehorn (Russian)

Forging a nail header

Forging a campfire grill

Forging a shoehorn (Russian)

Forging a nail header

Hammer therapy helps US military

For this issue of Moving Metal Magazine, I interviewing Chad Caylor of Reforged. I met Chad this year when I was invited to teach a knifemaking class and fell in love with his work and the program known as Reforged. Chad is a retired U.S. Army combat medic and Reforged is a peer support group teaching veterans and first responders how to make a knife. The program helps with post-traumatic growth and recovery. Chad’s wife is a licensed professional counselor and she provides free services for the program.

Knife-making class at Reforged led by Forged In Fire champion Billy Salyers

Salyers: Tell me about the nickname for Reforged.

Caylor: We call it hammer therapy. We have people in the shop almost seven days a week getting their hammer therapy in.

Salyers: What a great concept. Tell us a little about how Reforged got started.

Caylor: It kind of just came together. My youngest son graduated high school at 16, and when I asked him what he wanted to do next, he said he wanted to be a knifemaker. We wrote tons of knifemakers until we finally met Daniel Casey. He offered my son a class. As I was watching, I thought the whole process was a great metaphor for recovering from a traumatic experience.

military veterans

By Billy Salyers Forged in Fire champion

We started talking about it when I got a call from a friend who asked when I was going to start the program. I told him I was about 10 years from having the necessary skills, but there was a vet in need, so we went ahead and made a knife with him, fumbling our way through without the proper experience or equipment.

He enjoyed it so much that he told some others who were struggling. They called me up and we did a class. My kids and I ended up training with Daniel. And as the program started growing we got lucky when got Forged in Fire champion Tobin Nieto to join our program. He helped our skills tremendously.

Since then, we’ve gotten pretty good at teaching our curriculum. Our class size in now 10-16 students per class and we’ve started growing our own instructors.

Billy: But your program isn’t just a knife class.

vets and first responders feel discarded or used up when their careers end. By using these recycled materials, we are taking something that someone discarded and forging it into something beautiful. Being as smith yourself, you know that when you put that steel in the fire you sometimes think, “Man this steel isn’t going to make it.” We relate that to a traumatic experience: it could be combat, abuse at home, sexual assault, whatever the trauma is. At the time, you think you might not make it through the trauma, but you can because you are strong like the steel.

Caylor: Exactly, our program is not about the knife. The knife is just a tangible reminder that there is someone there to call if they are in a bad place. We could teach the class in a day or two, but we have a three day program so we can really focus on those talking points.

Billy: Tell me about the Reforged metaphor.

Caylor: We use mainly recycled materials. A lot of

Billy and Chad share a moment

We liken the quench to that point where the trauma makes you brittle, but then in the heat treat, we get the steel to the optimal hardness. Then its just about prettying up the blade. We always have them draw what they think they want to make and at the end compare the two. They are rarely the same. And that’s kind of like life.

Sometimes you think you’re going to go one direction and then a higher power calls you in a different direction. I didn’t think I was going to be a knifemaker.

Billy: I never dreamed I would be either.

Caylor: You don’t always end up with what you were working towards, but it can still be beautiful. The knife is like the person. It’s perfectly imperfect.

Billy: What a great statement. At this point, this program has grown a lot, right?

Caylor: We’re booked throughout 2022 with more than 70 people on the wait list. Our goal is to be able to do more classes, but finances are a limiting factor. We do classes once a month and a special class when we have guest instructors like you for our alumni

We also do special classes when we find someone in a bad spot that desperately needs it, but those are set up on a one-on-one basis. We don’t turn people away. We make it happen.

Billy: That requires a lot from your family right?

Caylor: My kids run the program. Our daughter set up the infrastructure. My sons are our smiths and instructors and have been from the beginning. My wife does the counseling and the behinds the scenes stuff…and I just kind of talk.

Billy: You’re too humble. You make the atmosphere special. Tell me about how the program works if I’m coming in for the weekend.

Caylor: The first thing we do is explain the program and say, “We’re going to show you how to do it,” and then we walk away. A lot of these guys struggle to ask for help and we’ve built it into the program to make these guys ask for help. We keep them busy on purpose with little talking on Friday. This helps people with high anxiety. It gets them used to seeing each other. We share lunch together, pile around the tables and force them together at that point. It makes us be closer together without realizing. Conversation happens naturally.

People can stay after if they want and generally quite a few do. It’s very methodical. The next day, we try to quench by lunch. Then we do “The Huddle.” Past alumni can come in for this. It’s kind of like a group therapy geared towards people with shared experiences. It’s freeing. One of the instructors talks about their own struggles. And then we talk about if we are in a good place. If we are, great, and if not, we work through it.

Billy: What’s your favorite success story.

Caylor: Well, we’ve had a lot, but we’ve had people who have recovered from being suicidal. We’ve had a lot of people whose dynamic has changed over time through coming here.

Billy: How is Reforged funded? It seems like there’s a tremendous cost.

Caylor: There is. There’s never enough equipment and with a growing demand for what we do, we never have enough 2x72 grinders or anvils. We’re trying to save for a power hammer because we have a lot of amputees who would benefit from something like that. We have stations for people with wheelchairs.

A bit of time of the belt grinder as Billy shows how it’s done

We get some small donations, but every amount counts. They mean a lot to us. Sometimes our alumni do Facebook fundraisers for us and that’s really nice. But, most of the funding comes from my family.

Billy: When I was with you, the atmosphere felt a lot like a family. You mentioned alumni. Is it accurate to say that once someone becomes a Reforged alumni, they are part of a larger family?

Caylor: Yea, we welcome everyone to the Reforged family. When we welcome someone for the first

Billy demonstrates for those in the knife-making classtime we say, “You get in for free this time but after this you gotta get your hugs.” Now if people come in and I don’t give them a hug right away, the hunt me down and give me a hug.

Billy: One of the newest developments in your life is a retail store. Tell me about that.

Caylor: That’s Caylor Forge, which runs Reforged. A significant amount of the funds from the store will go to Reforged, but we also want to allow some our alumni who can’t hold a job or work fulltime to sell their goods or even work there. There will be an entire wall devoted to Reforged to help grow the program.

Billy: You’re also going to have wares from smiths all over the world right?

Caylor: Yes, and we’re going to have a humanitarian section for smiths we are working with in impoverished countries to help grow their businesses. We are looking for people who give back to their community like a smith in African named Isaac who teaches the kids in his village. We want to help him get to the point where the kids working with

him are forging in shoes.

Billy: That’s awesome. As we wrap things up, tell me what someone who wanted to support this program could do.

Caylor: They could go to our website www.reforged.org and we have a donate now button or they could just contact me directly.

Billy: Chad thanks so much for taking the time to talk about Reforged with me and I look forward to seeing how the program grows in the future.

God bless and forge on.

MoverFeaturedofMetal Meet Oscar Duck, British artistic blacksmith

‘I would like to say that I try to create art – a piece of work that has a character about it and can tell a story’

The digital and virtual world has closed the distances between people. It’s nothing anymore for people on either side of the Atlantic Ocean to communicate easily. Moving Metal recently had a chance to catch up with Oscar Duck, the 19-year-old blacksmith from West Bradford, Lancashire, England.

Moving Metal: You mentioned that you began forging at age 13. How did you get exposed to blacksmithing that made you want to give it a go?

Oscar: The first time I ever saw a blacksmith in person was when I visited a Victorian model village. I must have been around 10 years old, but I have a very clear memory of the blacksmith. At the time I was not thinking I wanted to be a blacksmith but was definitely interested in it.

Three years later I wanted to make some steel arrowheads for a set of arrows I was making so I went to YouTube. Today, I continued to learn from blacksmiths on YouTube such as Rory May and his Forging Friday videos. This was when I really began to think I could be a blacksmith and I developed a desire to learn.

MM: Were your parents supportive of this?

Oscar: They have always been supportive. My dad tells the story of when I made the first forge, saying to himself ‘good on him for spending months making

blacksmithit and it does not matter if it won’t work.’ He was surprised when I pulled a glowing piece of steel out of the fire. They’ve been supportive all the way through my blacksmith life and appreciate it when I get the time to make them the odd thing or two.

MM: Does your age play a factor in being a blacksmith?

Oscar: I’m not sure I fit people’s stereotype of a blacksmith. When I was younger, I can remember demonstrating at shows with my dad. I would be forging, and he would be running the stall. People were surprised, after looking at my work, to learn that I was the blacksmith and not him. Maybe a bit of judgment there, but on the whole, people were and still are very supportive.

I am still young, and I have a lot to learn about blacksmithing. Other blacksmiths I know have always been supportive of me and other young smiths. I am grateful to be part of this community.

MM: Describe when you began. What were your first tools? Your first projects?

Oscar: Looking back, I did rather throw myself in at the deep end trying to forge socketed arrowheads. After, I began to explore other projects. I made a couple of knives, but then went on to the artistic side which is what I prefer. I started forg ing leaves, scrolls, other natural forms, I then ap plied these to products such as bottle openers and candle holders.

I soon realized that I needed better tools. I went back to YouTube to look up how to make tongs and had a go at making a pair. I still have that pair to day. Then came about the dilemma of forging out hand tools, such as chisels, fullers, punches etc. I can remember really struggling with this as all the steel I had was mild steel I found on the farm and I did not really understand heat treatment or even the different grades of steel.

So, more YouTube. I concluded that I needed some spring steel. I can remember finding an old coil spring on the farm and it felt like I’d found treasure. All the steel I used was scrap and the charcoal I made myself. The idea

of spending money on steel was silly to me because it was all around me. When I did find some high carbon steel it was my most valuable resource. That coiled spring helped me explore heat treatment and make quite a few usable tools.

Also, around this time, for Christmas I got my first anvil. It was a little cast iron anvil (probably around 10 kg) which helped so much compared to the sheet steel strapped to wood that I had been using. It was also this Christmas that I got my favorite ball pein hammer, which I still use extensively today.

: How did you get introduced to Bill Carter at Trapp Forge and can you describe your three-year apprenticeship?

Oscar: When I was 15 I submitted for an award. Part of this submission was to demonstrate a skill which you have to show improvement over the course of a few months. I needed an assessor to judge the piece that I made, to see if my skills as a blacksmith had improved. I got in contact with Bill Carter as he was a local smith and asked him to judge my work. I went to see Bill with some items I had forged previously so he could see where I was currently. I think it was the next week that Bill gave me a call to come in on that Saturday. I began a part-time apprenticeship from that one call. I’d go in every

Saturday and forge all sorts of things. Usually, I’d make smaller items, which were generally, pure forging, so bottle openers, fire pokers and the like. I also worked on bigger projects such as gates and railings and it was then that Bill taught me about welding. I got plenty of practice. We did some crazy jobs as well such as bending eyes for big shipping buoys which the starting stock was 90-mm solid round bar.

A fusion of art and craft is definitely an approach I take as an artistic blacksmith

I was also very lucky to learn how to use a power hammer with Bill. He had a hundred weight and a three hundred weight clear space Massey power hammers. I can remember him saying he’d teach me how to run them when I was 16. It was like waiting to learn how to drive. It was amazing to learn on those hammers and I feel very grateful for even being able to have a go on a Massey power hammer. I am definably missing them in my own

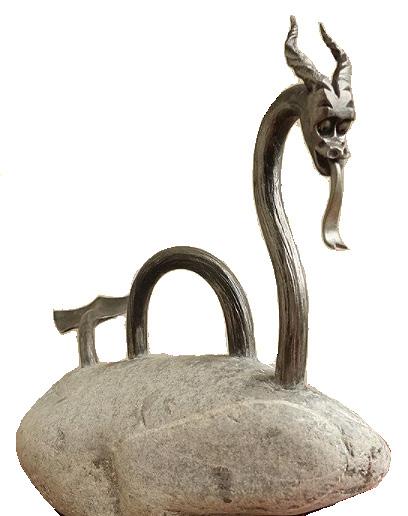

little workshop. Bill introduced me to forging animal heads. The ram’s head he taught me was his father’s design. His attention to detail in these heads makes them stand out. I am privileged to learn from him. I now make my own version of this ram and if you look at mine, Bill’s and his father’s you can tell the difference between them. I have developed my own series of animal heads now including dragons, horses, cows, dogs and many others. They all stem from the ram’s head design that Bill taught to me.

It was the best time of my blacksmith life. I did not have to worry about much, I was there to work and make things to sell, but also to learn and have fun. I owe Bill everything and I learned more with him than I realize.

MM: Your work was described by a gallery coordi-

nator as “a scintillating fusion of art and craft.”

Oscar: I would say that a fusion of art and craft is definitely an approach I take as an artistic blacksmith. I would like to say that I try to create art – a piece of work that has a character about it and can tell a story. Whether it is the facial features on a ram’s head, or the overall effect created by the design of a set of gates. In all my work, and indeed any blacksmith’s work, a story is told not only in the final piece but also how it was made by the smith.

MM: You said that you really like projects that exhibit a natural form. Was this something that emerged from your time with Bill?

Oscar: Designing with nature in mind is definitely my favorite way of designing and I draw a lot of influence from the natural world, as well as the school of art nouveau design. I picked up some of this from Bill. One of the main traits I picked up from Bill is trying to create natural forms that are realistic. A lot of smiths will stylize nature in their work, which in some applications works perfectly. However, trying to create something that exists in nature, I would say, gives your work value as people can connect with it.

I am also a big fan of Stephen Lunn’s work, a smith from the northeast of England. He captures nature in his work perfectly. His seaweed sculptures including seashells, driftwood, lobsters and other sea life, really are something special. I take inspiration from Stephen’s fluid design form, combining that with Bill’s realism approach to natural design. MM: Speaking of other smiths, what other smiths do you follow or have influenced you?

Oscar: I have mentioned Bill Carter at length as well as Stephan Lunn, both of whom I greatly admire. I also did a week’s work experience with Annabelle Bradley when I was 15. She has influenced my work. Annabelle has a smithy that is hundreds of years old. She practices traditional methods of forging with minimal power tools. My time with her made me see blacksmithing in a different light. I also follow smiths online. I mentioned Rory May before. I also followed Alec Steele in his rise on YouTube as well as Torbjorn Ahman and Joey Van Der Steeg. In my own work I take more inspiration from Joey and Torbjorn. They have an artistic style

to blacksmithing.

There are plenty of other smiths that I follow on Instagram, Thomas Gontar, beautifully forged railings and gates. Also, Jake Hedge, I love some of his leaf work. Conrad Hicks, a blacksmith from South Africa who creates some beautiful, forged copper sculptures. One last mention, loving forged heads myself,

I am in awe of Peter Walkers human heads, he has a real talent and particular style that creates some amazing pieces.

blacksmithing community what it gave to me: free teaching. If I can create something that helps people get into blacksmithing then it is worth doing.

Designing with nature in mind is definitely my favorite way of designing and I draw a lot of influence from the natural world

MM: I’ve been following your YouTube channel for about eight months. What would you say your goals are for your channel?

Oscar: One reason for video was from a business point of view. I would film myself making something that I sold and then could put a link to the video on my website. This means when people are browsing through, they can click on a video to see me make the product they are thinking of buying. I thought that this little piece of humanity, in which a customer could see me, made my small business real, rather than just an online website. The second reason is to give back to the YouTube

I find my channel is changing and developing into my hobby. I enjoy the day-to-day forging to make products for customers. I also found it left me no time to explore the things I wanted to forge. The videos have given me that drive to make these things. For example, a Viking longship I recently made. I like the process of directing the filming and then editing the videos to try and create something that is educational and entertaining.

MM: Give our readers a sense of who you are. Gives us some insight into you.

Oscar: I have played rugby for a while and I now play for Clitheroe 1st team. We have not been able to play during the pandemic. I am very much looking forward to getting back into it and playing again next season. It is a change of scene from the forge but I do like getting out there to have a run around the pitch. I play outside center, so I get plenty of running.

I am lucky enough to live in the countryside of Lancashire, England, with fields, streams and

woods at my doorstep. It can be peaceful to get away from a noisy forge every once in a while.

MM: You do forge a variety of things, from artwork to tools. What’s your favorite thing to forge at the moment?

Oscar: Currently, my favorite item to forge has got to be the ram’s head. It is the only animal head I make that does not involve modern welding, so is a pure forging. It also has a sentimental value to me in that Bill taught me how to make them and reminds me of my time at Trapp Forge. However, mainly, because I think they look cool.

MM: You mentioned forging the Viking ship? What inspired you to take on that kind of project?

Oscar: The Viking longship was just something that I wanted to make. I have a little book by the side of my bed in which I make a note of things I want to forge; I often think of them when I’m going to bed or if I wake up in the middle of the night. Originally, I wanted to make a pirate ship with multiple masts and decks and fit up with cannons. I realized that this might have been a little ambitious, so I decided to downsize and go with a Viking longship first. The pirate ship could perhaps be a later project. I am also interested in Viking history as it is very closely linked to the history of England.

MM: Describe your current shop.

Oscar: Most of my forging equipment is all hand tools. I prefer a little hammer for general work, around 2½ pounds. I tend to use my ball pein hammer and it does the job well enough for me. Often, I am forging lighter stock anyway, I very rarely forge using stock larger than 16 mm. With that being said, one piece of equipment that my arm would be very grateful if I got is a power hammer. Yet, I don’t have any space for one in my little building. I do have plans to expand at some point. I am looking forward to that day and the opportunity of buying a power hammer. Also, maybe a forging press as well.

The welder I have is a little 160 amp stick welder. I miss using a MIG Welder and in the future I would like to buy a MIG and TIG welder. I also have a plasma cutter which I run off a little 24-liter air compressor; this was something I never thought of having, but now that I have it, it makes sheet work, such as cutting leaf blanks, so much easier.

MM: You have several anvils you work with in the shop. Would you describe each of these and how you acquired them?

Oscar: The first proper anvil I got is the smallest of the ones I now have. I bought it for £200 when I was 16. It still sees use today as it has a very pointy horn and so is useful when making tight bends or narrow eyes. Also, because it is the first anvil I purchased, a lot of my hardy tools fit that anvil. I have never investigated where or when it was made, I think it probably weighs around 110 pounds. After Bill downsized from Trapp Forge I bought his medium-sized anvil I own from him along with the cast iron stand that comes with it. This anvil is very useful as it has a pristine edge. When forging out tapers this is not wanted, but to create a sharp shoulder or whenever you need that shape edge. It is incredibly useful. The only markings on this anvil is its weight, which is 150 pounds.

I then bought the huge anvil people see in my videos now off Bill earlier this year. This thing really is a beast and is the anvil I do the bulk of my work on. There are no markings unfortunately, but it weighs at least 400 pounds.

: Since you’re still early in your career, what skills are you looking to add?

Oscar: There is so much more to blacksmithing than I thought when I started out. I feel as if I will never know everything that there is about the craft.

I have a small number 5 Norton fly press which is useful every now and again. I have a bigger number 8 Norton press, but I need to make a new handle for that one.

I would like to learn more about traditional forging, in particular, forging larger tenons than I am used to and other forged joints, to put together gates and railings. I have only scratched the surface with the possibilities of forge welding. It is not something that I often do and recently I have been experimenting in my own time with collars, to create tenons or finials, such as a ball on the end of a bar.

Another aspect of metalworking that interests me is

sheet work. I’ve never tried to do any sheet work or repoussé, but it is definitely something I am interested in. I would also like to try and do engraving. I think both would be from more of a hobbyist perspective than from a business point of view.

MM: What are your thoughts about keeping the craft of blacksmithing going?

Oscar: Blacksmithing has been around for millennia. Some would say however, that in the modern world we are not needed. However, I like to believe we are valued. I think the view of the public is to keep traditions like ours alive and so they support our local, small and large businesses. I think the demand from the public for handmade products is on the rise and blacksmiths can capitalize on that. From my own personal experience, the older generation of smiths have always been enthusiastic when they see a younger blacksmith like me. They have always offered advice and been friendly to me.

One thing I am worried about use of coal. I think it is very likely that when I am an older smith, I will not be burning coal, but gas, and indeed many smiths nowadays prefer gas. The next stage after that is not being able to burn gas. We must look at other options such as induction forges or perhaps, but I think less likely, charcoal. I think the future

is going to be a bumpy ride in terms of our heat source, but I believe we can adapt to carry on. MM: Have you done any collaboration with other smiths, or those you’d like to?

Oscar: The only collaboration work that I’ve done has been working with Bill. After he downsized from Trapp Forge, we have kept in touch and when one of us has a larger job we help the other. So, we do have a bit of collaboration process in those projects. The two that come to mind are a set of chandeliers we made and a big set of estates gates I am helping Bill make.

I would love to do more collaborative work in the future. I’d like to do something with Stephen Lunn at some point, because I love his creative style. However, I think this would be more of a master and apprentice type situation rather than a collaboration.

Also, I’d like to work with other smiths more my age. One who comes to mind is Nate of Nate’s Forge. He is up in Scotland, so not too far away from me. Again, I like his style of work and his wandering blacksmith videos on YouTube. You can view Oscar’s YouTube channel here You can access Oscar’s Instagram here

Design: process and

Learning to design well has been one of the most challenging aspects of my career as a blacksmith. This is in part because I did not come to blacksmithing from a fine arts background and had no formal training in art or design prior to starting to forge steel.

Once I did begin my career as a blacksmith, many of the learning opportunities available to me, such as blacksmithing workshops and conferences, focused on the technical and process-oriented aspects of forging rather than on design.

Learning the basics of design was a process I had to undertake on my own. Luckily, I was exposed to good design in my early years while spending time as an apprentice in the workshop of Tom Joyce, who is the most influential mentor I have

by Caleb KullmanCaleb Kullman, shares his approach to design as a blacksmith and fabricator. His studio is located in Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA, where he produces art, architectural and functional projects for clients all around the world.

had over the years. There I learned the foundations of good design principles and practice, concepts that I was able to build upon as my career evolved and experience progressed.

After I had been forging for a number of years, I also took classes with Rick Smith at the Peters Valley Craft School, and with Doug Wilson at the Penland School of Crafts. These classes furthered my understanding of what constitutes good design and the design process. These were invaluable in my growth as an artist and designer. I also enrolled in several design and drawing classes at Colorado State University to further my education.

I combined these various sources of knowledge, inspiration and experience in design, along with much trial and error, into

and inspiration

my current design aesthetic. Put simply, my aesthetic is contemporary in nature, without excess ornament or frivolous detail.

When I begin to explore a new project, I often think about forging technique and process and work to create simple forms that directly reflect how I manipulate and transform the material. These forging processes - dramatically changing the dimension and shape of the materials I work with, adding texture, punching holes, fire welding, and using expressive joinery - allow me to reveal the beautiful qualities of the materials I work with and to transform hard, unyielding metallic bars into visually captivating forms with texture, depth and softness.

Because the forging process and the materials I use have largely remained unchanged for hundreds,

if not thousands of years, my work inherently shares certain qualities with historic works in iron and with forged work by other blacksmiths from around the globe. Membership in this community, through time and over distance, is one of the most powerful aspects of the craft for me. It also presents a hefty challenge to me daily – to create something new. This challenge is always in the back of my mind when I begin the design process.

In architectural work, unlike art, there are always functional requirements that my work must meet. These requirements constrain the scope of the work to a degree and inform early design decisions. Creating a list of functional necessities for a project is often where I begin the design process. I often add to this list abstract concepts that may be helpful or pertinent to the design. These concepts might stem from emotions, actions, historical or cultural context, or physical properties that I might want to convey with the design.

Once I have established this list of pragmatic concerns, I begin more aesthetic exploration. Early in my career, I frequently looked to ironwork by contemporary and past masters and to historical precedents for inspiration and guidance. This was useful to me as a less experienced smith; it pro-

vided me with a technical road map with which to approach a project and allowed me to see how other smiths solved similar design problems. The downside was that it often led to designs that were too

obviously derivative of other’s work or of historical pieces.

Another approach I have taken, and sometimes still do, is to refer to specific details in the architecture itself, and replicate or play off of them directly. This technique can serve to unify a space by reinforcing a cohesive set of details throughout a project, not just in the ironwork. As an example, I designed and built a set of fireplace doors for a beautifully crafted timber frame home and used the shouldered mortise and tenon joint details found in the building structure as a departure point for my hinge details. The design and craftsmanship of the doors echoed the larger structure itself, reinforcing the handcrafted aesthetic as a whole.

More recently, I want my work to have more context and meaning and to tell a story. If we can connect our work in a meaningful way to a larger story, it makes the work more compelling. Often, I look at historic objects that were made by blacksmiths, but are not necessarily meant to be decorative or architectural, or directly related to the type of project I am designing. These objects can be utilitarian objects such as tools, household objects, parts of old machines, etc. Often, upon close examination, small details of how the piece was originally made can have beautiful aesthetic qualities, even if the intent of the maker was pragmatic.

I take these small, under-appreciated details and expand upon them or transform them into focal points of my architectural pieces. Using them as inspiration ties my work to a larger historical context, aesthetic vocabulary and the long tradition of blacksmithing that I am continuing to perpetuate. A couple of years ago, I was asked to design and build a railing along the stone walls of an historic acequia (irrigation ditch) in downtown Santa Fe. The acequia has been providing irrigation water to the community for hundreds of years, and al-

though no farming occurs in this part of town any longer, there is still water in the ditch during the summer months.

I wanted to link my work to the long history of the place, so I settled on the simplest of tools – a Spanish colonial cultivating hoe – as my source of inspiration. The profile of the eye and the shoulders of the hoe blade, undoubtedly similar to the ones used in this location to grow crops to feed local residents, became the profile for

the repetitive decorative element in the railing panels. I believe this connection to history and place creates a more compelling final product for the site. Once I have mulled over a design in my head for a time, and possibly have a vague idea of what direction I would like to head with it, I begin to sketch. Loosely at first, quickly jotting ideas down on paper and not worrying too much about finesse, details, proportion, etc. Often these drawings are very loose pencil or charcoal sketches.

One technique I learned from Doug Wilson was to stand at my layout table with large sheets of newsprint spread out and use charcoal to make quick, gestural drawings. From there, I pick out forms that I think have potential and start refining the sketch.

Once I have refined the sketches concrete direction, I sometimes and begin to try to make steel. This inevitably leads and tweaks to the design After some trial and error, a design and begin working presentation drawings, using pencil. Recently I have moved cess onto a digital tablet and to create drawings.

Going forward, I am hoping ital media for a streamlined the paper sketching and paper-based drawings, if I can. In the have added 3D modeling sometimes model details three dimensions. This helps for me, my team in the shop, able to model a piece in 3D, impose it onto a photograph powerful visualization and time consuming).

Once the project has moved phase and into the production mensioned CAD drawings This allows for greater dimensional hopefully no surprises at One of the most important about creating compelling is that the process takes time not come quickly nor easily. the time to mull a design speak.

I often begin to sketch on sit for a few days, come back to work, repeating this several allow ample time and try cause of time constraints dissatisfied with the final Good design doesn’t just tured with time and effort.

Caleb Kullman Studio website Caleb Kullman Studio Instagramsketches and have a more sometimes go into the forge some of the details in leads to changes in the idea sketch.

error, I typically commit to working on more polished using a drafting table and moved some of this proand sketching software

hoping to rely more on digstreamlined workflow and reduce paper-based presentation past five years or so I to this workflow, and or entire projects in helps with visualization shop, and for clients. Being 3D, render it and superphotograph of the site can be a and sales tool (and very

moved out of the design production phase, I create didrawings to actually build from. dimensional accuracy and installation.

important lessons I have learned compelling and powerful designs time and effort. It does easily. I must allow myself over, to chew on it, so to

on a design, then let it back to it, and continue several times. If I don’t to force a design out beor deadlines, I am often product.

happen – it must be nureffort.

website Instagram

The necessity

For a budding blacksmith and bladesmith, one of the most important steps in the learning process is failure. From the tools you buy (or don’t) right down to the technique that is used to accomplish a simple shape or pattern. When our processes fail we may become frustrated with the process and give up altogether.

Think of when you said you were going to learn that new musical instrument, or language or craft. You likely expected to be playing a popular song, speaking fluent Japanese and throwing clay on the potters wheel in no time, like a pro. The sad reality, however, is that you usually only ended up learning the intro to Smoke on the Water, throwing a lopsided lump of mush on the wheel and saying sayonara to Japanese. Bladesmithing and blacksmithing are similar endeavors. It’s hard work. It takes hundreds of hours of doing it to become competent. Failure begins at the beginning and continues until you’re pushing up the daisies.

My learning curve with bladesmithing has been very steep. I struggled to produce what I wanted for a couple of years, and then one day, quite suddenly, I was much better at it than I was before. I’d say I’m in the middle of climbing the curve, but that is only possible because of the many failures I have experienced throughout my tenure as a bladesmith.

When I decided that smithing was for me, I started a list to get organized: Hammers, a propane forge, an anvil, some tongs, and a post vise. I ended up buying a forge that was too small, an anvil that was dished, a post vise that was too...used, and half of the tongs I bought were completely unnecessary for what I was doing. What I got right were the hammers: a rounding hammer and a cross peen hammer that were forged by Torbjorn Ahman. I still use them today. Early on, I didn’t know when things were wrong. I had watched some YouTube videos, and read a couple of books, and thought “Eh, this will do.” I was wrong. I didn’t know anyone in the smithing community with whom I could confer. The moment I hit that hot steel on my anvil, I knew I was in way over my head. Don’t get me wrong; I loved it. Instantly. But I knew that I was in for a long hard slog. I needed help.

I cannot stress the following enough: wishing to take up smithing should learn a few things before you begin. ployed as smiths. Get a mentor. There area that is guaranteed to be chock-full smithing for decades. The amount from them is the most valuable information two meetings are usually free, and anvil with guidance.

I did not do this on day one and ended niques that I should have been employing skip this step. Humble yourself at the do this until a year into my smithing

When I started forging, I bought steel hammering away with almost no clearly pieces that were too big and ended of propane on one piece that ended to look. I’d call it done without having drive me nuts. As time went on, I gradually I should have learned earlier through My failure on the anvil in the early knowing where to start. But what happens

of failure

by Joshua Frost Forged in Fire championenough: the number one thing anyone should do, is go out into the world and begin. Talk to smiths who are emThere is a local ABANA group in your chock-full of old timers who have been of learning you can accomplish information you can obtain. The first you can get in the fire, and on the

ended up having to relearn techemploying in the early days. Don’t the teaching of masters. I didn’t smithing journey, to my cost.

steel from a scrap yard, and started clearly defined objective. I bought ended up wasting gallons and gallons ended up not looking how I wanted it having forged it properly, and it would gradually learned basic things that through in-person instruction. days can be attributed to not happens when you fail at a project when you are years into your journey? Yes, it still happens. It may not be as frequent as it was in the early days, but it still happens. Sometimes with no rhyme or reason that is readily apparent.

I remember attempting to forge a Damascus billet years ago. After the second heat, I noticed significant delamination in the billet. I tried to save it with subsequent heats, but the delaminations

wouldn’t weld. The billet failed. Or, more importantly I failed.

What had I done wrong? The steel was clean, welds were clean. The billet was soaked in diesel and heated appropriately. billet was put in a 25-ton press and squished to oblivion.

I learned that I had pressed with too much force. I blew apart the layers on the sides. The search for the source made me reevaluate my entire process. I went over it step by step. I paid particular attention to where and how steel. The subsequent billet was perfect.

Failure isn’t something we like to talk about. However, failure is a natural step in the process that helps us learn nique. Whether it’s grinding a bevel, or forge welding mosaic tiles, it is absolutely critical.

Another good example of extremely useful failure is my first attempt at mosaic Damascus. I forged some explosion mosaic the first time I tried it. I forged my flats and crushed Ws. I forged the 3/4” squares and cut my tiles. I made forge welded the tiles. The resulting billet was beautiful, but useless. The tiles didn’t forge weld properly, and the attempt at forging out a knife from it resulted in tile delamination, and the billet was ruined. 20 hours of work, of material evaporated before my eyes. It was an important moment in my journey. I had two options.

1. I could take the failed billet and throw it out the forge window along with all of my tools

2. Or I examine what I did, what went wrong and practice new techniques that had a greater probability of I chose option 2. I did more research. I read His Forge Burns Hot by Joe Kertzman, watched Chris Crawford’s mosaic DVD with demo from Chad Nichols, and endless hours of video on the subject. I spoke to smiths who do mosaic Damascus and learned better technique and practiced on non-pattern-welded steel. I perfected my own technique as an amalgamation of techniques of other smiths who had been doing it successfully for years, and then I tried it again, with flawless results.

While it’s important to fail, it’s also important to not let that failure stand. If you give up and let your failures consume you, then you will never be able to creatively realize the wonders that exist in your imagination. If the scientists and engineers of the space program decided to quit after their first attempted (and spectacularly failed) launch, we wouldn’t have a helicopter hovering around on Mars right now. The reaction to your failures is what will compel you to do it better, with more precision, and eventually, continuing success.

Find Joshua Frost on Instagram

appropriately. The source of the failure how I pressed the learn proper techexplosion pattern made a stack, and the subsequent work, and $100 worth success.

Creature features: An upsetting approach to forging animal heads

by Kees KlaassenForging animals can be daunting but also very satisfying. In this article I will discuss an upsetting approach that lends itself well for a variety of creatures, such as most mammals with ears. Use of a chisel is limited in this approach, but rather I use fullers to progressively push the metal to form.

Vice modification

My approach to forging these creatures is aided by a modification I made to my bench vice. I drilled and tapped two 10-mm bolt holes in the side of the jaws. This allows many fixtures to be attached for forging. Now, I can use any stock to support my work but also do double fullering that most people achieve with guillotine tool. Any scrap stock now acts like a bottom fuller giving you 3D forging capabilities.

then flattening the two opposing corners across the diagonal. This shape can be formed into the tool profile shown creating a very rigid tool. I tend to stay away from ball punches because they create these circle shaped imprints that can disrupt the lines.

Pre-form and pose

Upset the end of the bar at angle. For many of my figures, I use 20-mm round stock. This can be done in the vice, but I prefer to just strike the bar itself on the anvil.

Consider the shape of the creature but also the pose. In vertebrates, pose fulcrums around joints. But since we are manipulating metal that bends rather than swivels, it is important to determine the pose before forging.

If you’re not ready to tap holes into your vice similar results can be achieved with a type of removable saddle-type tool in your leg vice.

Tooling

The look of my creatures is achieved by special fullers and chisels which have an elliptical side profile. This allows them to get into many different curves or plow through the material if used at an angle while preventing the corners from damaging the work.

My favorite style of hand fullers and small chisels is made by first forging a square taper

The techniques shown here are for a forward-looking pose but if you’re looking for something else it might be a good idea to start with clay or sculpting wax. I do rough sketches in wax before forging using only forge-compatible actions.

Most shaping is done with an 8-mm fuller. Start with dividing the end into halves creating the eye line. Then separate the ears creating an inverted T shape. Extend these grooves in to the side of the bar a bit isolating the three volumes. Maybe taper the snout a bit before forging an inverted V shape pushing the ears further back. As you go deeper this groove

will separate in to two steps: one forming the front ridge of the ear and one forming the eye socket and side of the nose. Work the sides of the bar isolating the neck and snout. This should look something roughly resembling a bear.

Forming and negative space

Note that the preform for different creatures is very similar. As I progress, I use different size fullers along the same angles I started with the T, V and the sides.

It’s easy to get distracted by the surface textures, scale and the glow preventing you from seeing the shape. Try focusing instead on the silhouette looking at the profile against a contrasting background. Sculptors call this concept negative space and it is very useful in blacksmithing since you can simply push the contours to where you want it. It might feel strange to look at your piece this way.

Detailing

After you’ve isolated the ears enough it can be a bit tricky to draw them out. Use some small stock supported in the vice fixture can help getting into the corners.

Eyes are easy to mess up and sometimes use a riveting punch. Often this creates realistic look start with the upper eyelids plowing the line in. Proceed with the both eyes. If your line is a bit off you start slowly with tiny taps at dull red a form punch.

I make my chisels for eyes by denting grinding the sides to an oval shape eye. is already isolated positioning is easy. feline and reptile creatures it’s nice to chisel.

Sculpting eyes could be an entire article tures and people the eyes are very important ter. If you can’t do it right consider keeping

The most common eyes are done with Of course they do not have to be round. finishes with doting the pupil with a forging cats or dragons. The problem

sometimes are best left out. Most smiths creates a stylized cartoon look. For a eyelids using a tiny fuller at an angle lower eyelids working parallel on you can do a lot of correcting if you red heat. You could still follow up with

denting a ball into a piece of H13 then eye. Since the volume for the eyeball easy. Many variations are possible, for to do the pupils with a small straight

article on its own. When forging creaimportant for establishing the charackeeping the face abstract.

with a hollow punch like for rivet heads. round. After shaping the eyeballs one center punch or straight chisel if problem with this is that if you’re a tiny bit

off you’re character looks drunk.

A few years ago I started making my eye punches on my lathe with a point in the center to make this easier. Still I was not satisfied. The gaze this creates lacks depth and looks cartoony. I was looking for realism. When discussing this with fellow artist @carolinevandensigtenhorst we looked at the wonderful eyes of the Mount Rushmore in the United States. They created the deep gaze I was looking for by making the pupils hollow leaving a small spot in the center simulating a shiny bit. I tried to create this effect by stamping the pupils in with a tiny riveting punch at an angle with moderate success. A tool this small is a bit too delicate for hot forging and is even harder to align than a center punch.

Mouth, teeth and nose can be done the same as the eyelids, using fullers then chisels working colder as you get more into the details.

If you want to open the jaw be careful not to curl the jawline by splitting the mouth from front to back. Instead forge the outside contours close to the final line and split from the sides so you can shape the teeth while everything is still solid.

I hope you find this of use and happy hammering to all of you.

Opposite: Klaassen using various punches for different eye effects.

Below: Klaassen using fullers and chisels when forming an elephant head.

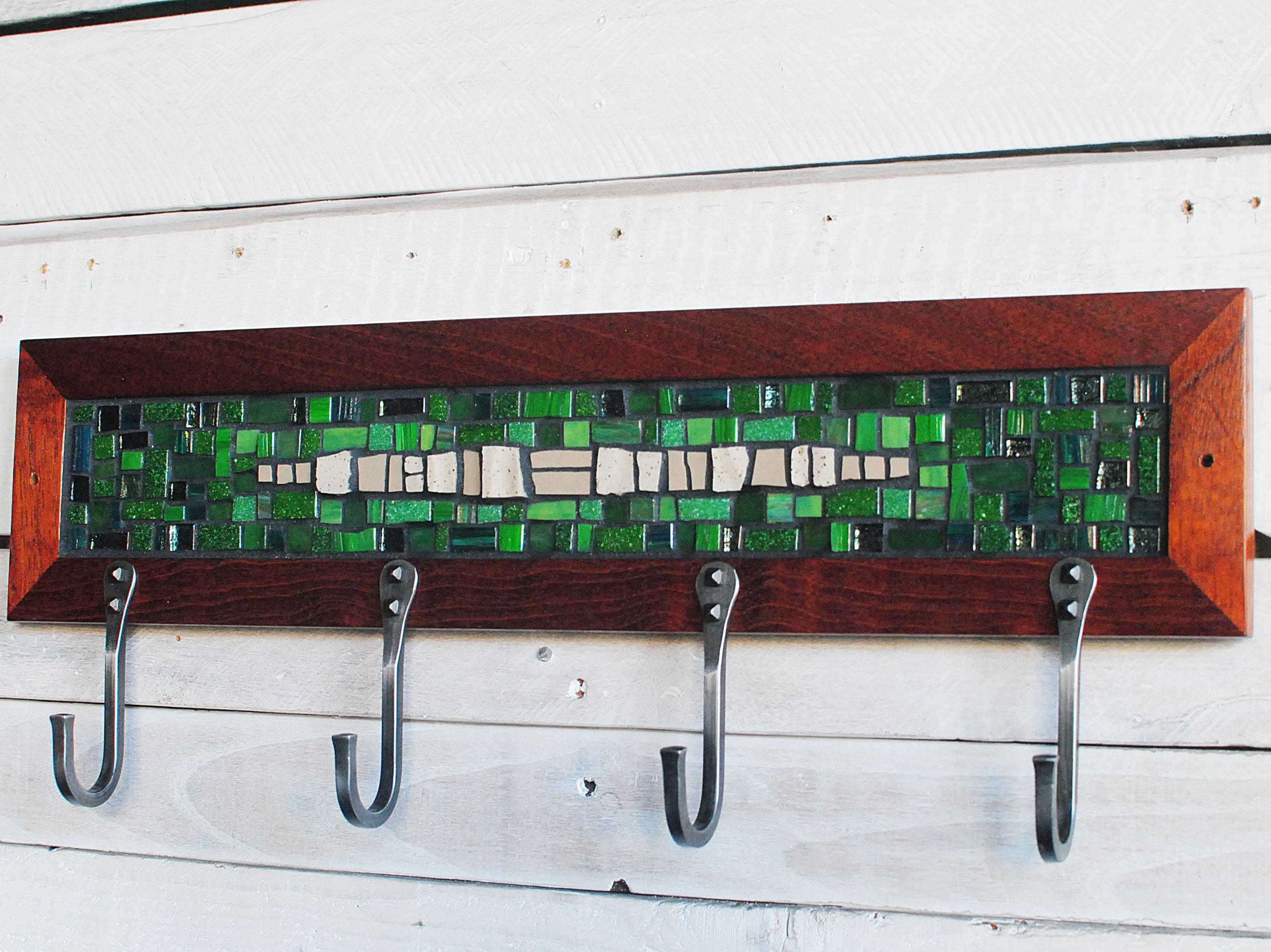

Couple marries and mosaics into

Phoenix Handcraft is a husband-and-wife design studio based in Richmond, Virginia. Kyle Lucia is a blacksmith and furniture designer and Johannah Willsey is a visual artist specializing in mosaics. Individually, and together in collaboration, they create commissions and original works of art, furniture and architectural elements as well as a line of functional and decorative retail products.

Johannah and Kyle met working in a picture frame shop. “You could say we have been making things together from the beginning,” Johannah said.

They both enjoyed working with their hands and spent the early years of their life together working on projects around the home and creating gift items for friends and family.

The seed of Phoenix Handcraft was planted one holiday season when they made a series of mosaic trivets in forged steel frames for several family members.

A strong background for each

Kyle got his start in blacksmithing through a class at John C. Campbell Folk School in North Carolina in the late 1990s. He was later hired by Stokes of England in Charlottesville, Virginia.

“I spent the next few years working under various smiths in the United States

blacksmithing

a unified whole

and the United Kingdom before I headed up the decorative metal division of a small metal fabrication shop in Richmond,” Kyle said.

While working in this capacity, he also completed his BFA in Craft and Material Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University in 2008, with a special focus in designing and building furniture.

Johannah earned her BA in Art History at The College of William & Mary in 2001. Having dabbled in various forms of visual art from a young age, she made her first mosaic soon after graduating college. “I knew at once I had found my medium,” she said.

She spent the next few years making mosaics and learning more about contemporary mosaic artists and techniques on her own.

She was later hired as the lead mosaic artist for a budding tile and mosaic company.

Approaching from two different vectors

Kyle’s design process often begins with a series of rough thumbnail sketches. Once he has narrowed down the specific design, he creates a finer to-scale rendering of the item.

“I’m a firm believer in the approach where form follows function,” Kyle said.

“Therefore, the human use of the final work is always taken into account. Furniture, railings and other similar elements need to function as well as a favorite tool.”

“I often like to start a design with a list of words,” Johannah said. “They might describe the mood or theme of the piece, the colors, style or inspiration.” She collects material she plans to use, often traditional material such as glass or ceramic with interesting found material like hardware or reclaimed pottery. A sketch follows from there.

Marrying two artforms

When working collaboratively, most often one will have an idea for an item they could make together, and they’ll use that first idea as a jumping-off place. Ideas come from clients, gaps in their portfolio or product line, needs in their own life, or

dreams and goals for larger items they’d like to make together. Sometimes prototypes are required, or they may evolve a product over repeated iterations. “For some of our larger projects, especially commissions, we will create a maquette to help visualize the item in the real world before creating the final product.”

Kyle’s style is clean and straightforward. His goal is to use traditional blacksmithing techniques to create folds, bends, connections and shapes that reflect modern design aesthetics. Johannah’s work is intricate and centered on color and texture. She creates both abstract and representational designs inspired by the natural world.

When working together to create small decor, furniture, or larger sculptural or architectural items, Kyle’s work provides the line and structure while Johannah’s work brings the color, and where pos-

sible, texture. Together, their work creates a warm sense of the unexpected combined with strong design.

A recent collaboration

One recent collaboration is a custom garden sculpture. A client familiar with their work approached them wanting a collaborative piece. Based on the client’s love of gardening, they created the design for this sculpture around native local plants such as arrowroot, cat tails, pickerelweed, and ferns. Kyle and his team would forge the thin leaves and vines, while Johannah would make mosaics supplying the color for the wider leaves and flowers. They created an organic design incorporating simple geometric shapes to represent the leaves and flowers.

Kyle developed a method for including mosaics in an exterior sculpture by fabricating steel trays that

would house the mosaics. Based on his to-scale rendering of the sculpture, he created a sample tray for a maquette that Johannah then filled in with mosaic. This maquette was submitted to the client for approval as a sample of what they could expect before they began production of the final piece. From there, Kyle and his team forged the steel framing and organic forms while Johannah created the mosaics to fill in the geometric shapes. In all, there were four steel tray shapes repeated throughout the design. The client requested the color for this piece be rich but subtle, so they went with a simple palette of four colors in gradients, one for each shape based on the leaf or flower it was meant to represent. They chose smalti for the material, an Italian glass with a broad range of colors that can withstand exterior changes in moisture and temperature. The mosaics were made on mesh, then

transferred into the sculpture, glued in place, grouted and sealed to provide extra protection from the elements. And finally, the sculpture was installed in the client’s garden for them to enjoy year-round.

Though most of their pieces are not collaborations, Johannah and Kyle demonstrate a delightful ability to join their crafts together to create art that is beautiful while remaining functional –skillfully demonstrating both, thus, making their work impactful. As a couple, they are an example of how cooperation between two creative, yet different, minds can bring beauty and joy into the world.

You can find more of their work at their website

‘I just like to play

Jennifer Lyddane didn’t set out to be a bladesmith, let alone emerge as a Forged in Fire champion winning the 2020 second-change tournament. But after a unique set of circumstances, this Kentucky mom and Army wife emerged as the Lipstick Blacksmith.

Watching her husband go through the process of being selected and competing on Forged in Fire meant that Jennifer Lyddane, a barber by trade, knew what she was getting into when she took her turn to appear in the popular History Channel competition show. Yet, what followed was no simple journey, but one full of learning and new friends and no small amount of anxiety.

A beginning blacksmith and bladesmith from Versailles, Kentucky, Jennifer has had two mentors in the three years leading up to her first appearance on the show. Her husband Jody, a military veteran who appeared in season five, has taught her much about bladesmithing. Also teaching her about blacksmithing was veterinarian and farrier Dr. Rick Redden. “I’ve been so fortunate to be able to obtain the knowledge I have from my two mentors,” Jennifer said. “Though, it’s been like drinking from a fire hydrant at times.”

One spark of interest in the craft came on a trip Jennifer took with Jody to a regional hammer in. Enticed to attend by the promise of a night out as

a couple away from home to celebrate their wedding anniversary, Jennifer agreed to attend.

Bladesmithing wasn’t her bag

“I was thinking that the event was real macho and not for me,” Jennifer said. “I was thinking that I’m not into knives.”

Yet, when they were leaving the hammer in the hook was set in Jennifer. One smith had forged a straight razor. “As a barber for 20 years, I knew this tool well but didn’t know you could forge one,” she said. “I looked up at Jody and quietly said I can make one and make it better. Of course not having a clue what I was talking about.”

She was determined and later ventured into Jody’s shop and attempted to make a straight razor.

“Though I had made my first blade, I didn’t form some great passion,” she shared. “But, it was Forged in Fire that had a lot to do with why I am now into blade making.”

Neither Jody nor Jennifer were familiar with

play with fire’

#lipstick_blacksmith

Forged in Fire until friends recommend that he go on the show. He soon made his application, and during the video conference interview producers asked if he forged with anyone else. He indicated that sometimes Jennifer joined him in the forge. At that point, she had forged three projects. The producers asked if Jennifer would be interested in competing. “He didn’t even talk to me about it and told them that I would appear on the show.”

Producers had preliminary plans for a family episode, Jennifer said. “Jody and I are thinking we’re going to do this and I’d just ride on Jody’s coattails.” When the reality of actually having to forge a knife on television set in, Jennifer got serious. “I started studying, doing lots of research and getting as much experience in the shop as I could.”

About 36 hours before the Lyddanes were to board

a plane to go compete, show producers told them the family episode was canceled. Undeterred, Jennifer called producers and made her case for Jody to still appear in the show. The producers agreed. Jody made it through the first round, but it was in the second round when Ben Abbott broke Jody’s blade. “It aggravated me because I knew Jody was a good bladesmith and could make it all the way.”

A new bladesmith

“At one point I had to stop barbering, which was really important to me,” she said. “But that’s when I started working with Doc Redden and he taught me how to move metal and how to forge weld and

really just taught me a lot of the fundamentals.”

By this time in 2019, Jennifer was spending any time she could in the shop or helping Dr. Redden. “It was therapy for me,” she said. “There was no pressure and Doc Redden was so easy to learn from and Jody taught me all about heat treating and the science behind it.”

Jennifer became aware that the show was seeking female smiths. “Once I was sure that Jody was supportive, we took the steps for me to appear in season seven and I was set to go.”

Once there, the experience was different for Jennifer than it was for Jody due to the pandemic. “They tested us a lot,” she said. “With the social distancing and separation from the other smiths when off camera, there just wasn’t the same camaraderie as there was pre COVID.”

Describing the process, Jennifer said that producers will line the four smiths up before the famous walk out. “At that point, it’s very real. I wondered what I had gotten myself into. That’s when the nerves kick in because when you normally work at your shop, you know what you’re going to do. In the show, you don’t know what you’re going to forge or what you’ll be faced with.”

Once she knew what she was to forge, she said time on the clock raced. “I crashed and burned.”

It was the special guard that proved a challenge for her. “I sat and stared at the work for 15 minutes just trying to wrap my head around it,” she shared. “You’re in a situation where you are using equipment that is different than yours, producers are asking questions, and you have to think fast and work fast.”

She said the handle was looking hideous but her goal was simply to turn in a finished weapon. “I believe when you start something you should finish.” However, her blade didn’t pass muster and she was eliminated and had to walk that hall of shame, but with her head held high.

“I wasn’t disappointed about being eliminated or even disappointed in myself,” Jennifer said. “I think like everyone else, you want your blade to be tested. When I got home I was thinking to myself, ‘I should’ve done this or should’ve done that’.”

The creating of that special guard nagged at Jennifer. She went back to work in the shop and set her-

self to figuring it out. From the time the show was shot to the time it was aired, was eight months. “That whole time I was working on guards. I counted eleven attempts before I got it right. I couldn’t give up. It was driving me crazy.”

A newer bladesmith

“Growth is an understatement for me in the difference between my appearance during season seven compared to the Second Chance tournament.” Her mental approached changed for the second appearance. “Before, I felt like I had to do everything the right way. That’s my normal mentality; you do things the right way so you don’t have to go back and re-do it.”

In September of 2020, she received a call from the show’s producers asking if she was interested in coming back to appear a second time. The show had planned a second-chance tournament with initial rounds being set as head-to-head dual competition. Contestants were those smiths who had been eliminated in an earlier episode. Her mental approach was a bit more laid back this second time. “Though I wanted to start what I finished with whatever weapon they assigned us, I really was there for the comradery,” she said. “I knew I was going to make new friends and I’ll probably learn something and have a great experience again.”

Mano y mano

said. “I tried to encourage Gordie to keep going, but I also realized I needed to focus on what I was doing because I had to finish what I’d started and keep my head in the game.”

Both turned in a blade and Jennifer said that she and Gordie both were less focused on winning but just wanted to have their blades tested. “Never in my life would I have thought that some of my

The duals round was a Beat-the-Clock format where she and her competitor had to build a knife in five hours from start to finish, including heat treating. “I felt pretty confident in the assignment to create a san mai blade because I love to forge weld and was familiar with the process. I just thought if I can hurry up and get to making the handle, I’ll be alright.”

A bit of misfortune struck her competitor when his billet split following quenching. “I felt so bad for Gordie because I knew he was a great bladesmith and I knew he could do this any other time,” she

great friends would be these big bearded burly guys, but because of this show I have new friends in the bladesmithing world that my girlfriends that I’ve had since grade school don’t understand.”

With blades turned in to be tested, Jennifer said that it would be so cool to hear Doug Marcaida say it will cut or it will “KEAL.” It was during the testing that her motivations began to shift. “Now I began to raise the bar and it wasn’t good enough that I just finished, I want to hear Doug say those things about my blade.”

As David Baker was putting Jennifer’s blade

through the paces, she and Gordie were surprised at the degree of force Baker was using during testing. “I impressed myself because David Baker swung it very hard. He destroyed the clock with my blade.”

Her blade outperformed her competitor’s and she moved on. Yet, the idea of moving to the finals caused Jennifer to wonder who her competitors might be and their level of experience. “At that point, I’d had a total of 3½ years’ experience mak-

two-inch ball bearing and then had to salvage mild steel from the bucket of a rusted excavator.

“We’re all four cutting on the bucket to get our mild steel and I’m having a blast,” she said. “Here I am with three new friends but were all completely different, yet all of us trying to do our best work and doing a lot of grinding to remove the rust to get good forge welds.”

Though the smith next to her had his billet split, she felt that was an unfair way for her to advance, but she said she knew she had her own work to do. “I developed tunnel vision,” Jennifer shared. “Again, I wanted to finish what I started so I was not focused on what the other competitors were struggling with or how they’re advancing. I just have the mentality that they are always ahead of me so I’m going to keep working.”

ing knives. I’m feeling like I definitely must be the underdog and I’m now stressing out about missing work and missing holiday events with my family. But, I wanted to make people proud and that whatever I do is a reflection of my mentors.”

Competition heats up

Upon arriving at the set she recognized some of the finalists. “I immediately thought I was going home in the first round.” This feeling was reinforced when it was revealed what they were going to forge with.

The first challenge was to create a through tang chopping blade between 13”-15” of cutting edge using the San Mai technique. They were given a

She made it through to the second round. “I couldn’t believe it. I was supposed to be the one going home after the first round. So now I’m expecting them to throw something crazy at us with the handles and I know that’s my weakness.”

And a curve ball was what they threw when they asked contestants to use a foundry with brass as part of their handle make up. This was a completely new process for Jennifer and she had some difficulty. “James who made it through to the final weapon with me helped me understand foundry processes a bit better.” After several pours, she eventually got enough brass formed to create a guard and a pommel.

After a healthy amount of epoxy and peening things together, she spent her time refining the handle and etching the steel and less time in honing the edge, so she thought she didn’t have as sharp a blade as she should. But she finished and presented a blade for testing and that’s when Jennifer had a few personal issues.

‘I think I’m going to pass out’

“Both times when I’ve had my blades tested I got jittery,” Jennifer said. “You have all this adrenaline building up and when J. Nielsen took my blade to test it, I began to hyperventilate and the camera and microphone caught me whispering that

I thought I was going to pass out.” She indicated that she barely remembers her blade being tested. “I remember I felt as though I couldn’t breathe, and I went down on one knee and wondered why everything was getting dark,” she explained. “David Baker chuckled and asked me if I was okay and I raised my arm up and said I can’t breathe.” She passed out momentarily and awoke laying on the medic’s lap. Doug Marcaida’s presence, one of the show’s edged weapons experts, was helpful because he also is a respiratory therapist and was able to help people understand how to help Jennifer by reducing her oxygen intake.

“Looking back it is hilarious and embarrassing, but relationships formed with the medic and with Doug and the show’s producers,” Jennifer said. “The guys were cool about it and I picked on myself more than they did.”

Though her blade wasn’t the sharpest, it held up well through testing. Two of the smiths’ handles came loose. “While we’re waiting for the results and judges’ decision, all three of us are saying we’re going home. When they announced I made it through the to the finale, my first thought was that

I had to call Jody because I had to commit more time away from the family during the Christmas holidays.”

At the home forge

She flew home on Dec. 18 and the next day the film crew arrived but she only had four days to forge her flyssa sword instead of the normal five. She was excited that the challenge was a sword because the Lyddane’s have a coal sword forge. “I wanted it to be challenging. I wanted it to be big. I didn’t want it to look like they were taking it easy on me because I am a woman,” she explained. However, the home forging experience was trying as well because due to show restrictions, Jody was not allowed in the forge. “That was stressful because Jody had customer knife orders to fulfill and he was not allowed in the forge or allowed to use any of his own equipment in the forge until I was done and the crew shipped my sword.”

Each day at her home forge was long. “I wasn’t used to spending 10 hours a day working in the shop,” Jennifer confessed. “I spent eight hours in the shop each day working on the sword. Then,

because of COVID, I’d do interviews with the crew after eight hours in the shop when normally, they’d interview you while you’re working.”

On the flight home before the finals, Jennifer drew the flyssa sword multiple times as her reference. The judges gave both contestants parameters to meet, including an animal-head pommel. “I knew right away I was going to forge a ram’s head for my pommel and use 5160 steel,” she said. “Yet, it wasn’t until day three when things started to come together, but I was rushing the handle. I quenched and heat treated on day three and I needed every minute of those 10 hours.”

The first time she quenched, she had warps in her blade but over corrected so when she heated it back up again and went into quench, it came out straight. She used two pieces of angle iron in a vice to help clamp the sword to help keep it straight.

Waiting for testing

Now she was faced with a new waiting game. Normally contestants go right back to Connecticut where the series is recorded. “It wasn’t until the end of February that we went back to present and have our weapons tested.”

Once back together, there wasn’t much time for comradery because her competitor missed a flight and came to the shop later than expected. “He was running on no sleep and so I was trying to be a cheerleader for him. I reassured myself that he’ll be fine after he wins.”

Facing testing once again, Jennifer admitted that she hoped they would not do the pig carcass test. “If they did the pig carcass test I really thought I’d throw up. Even seeing road kills makes me weezy. And then there it was.”

Her blade cut through the pig, though she felt she’d see other sharper swords do better, but she got to hear those famous words that her weapon would KEAL. Yet, her competitor’ sword nearly cut the carcass in half with one swing. “I was so happy for him. He had such a horrible time just getting there, so it was good his sword cut the pig well.”

The toughness test showed Jennifer’s flyssa sword to be worthy. Her competitors blade took a bend in the toughness test and so they went into things not knowing how it would turn out going into the sharpness test.

Tough strands of twisted silk was the first test and her sword cut through it easily. The second cord of silk was thicker and seemingly her sword didn’t do much to it. When her competitor’s sword was tested, it didn’t cut the first silk strand and the judge swung it a second time without much difference. It was at that point that it dawned on Jennifer that victory might not be out of reach. “I remember thinking that I might win. James’ pommel was loose and it didn’t cut through but I kept thinking that this cannot be.”

A new champion

After testing was complete, they left the forge floor for the duration of the judges’ deliberations. “But it wasn’t long before they called us back. “When Grady announced that I was the Forged in Fire champion, it was very emotional for me. I felt as if I had come a long way in 3½ years, yet I know I was not the best bladesmith in that competition of second-chance contestants. It took every bit of knowledge I had at the time just to get through the competition. I poured a lot of myself into that four days and I just stared at the sword and wanted to take it home.”

“Forging and blademaking helped me get out a very dark and depressed time in my life. And Forged in Fire changed my life,” she said. Bladesmithing was not what she thought she’d be doing with her life, but after the show, things were different.

Arriving home after the show was over, she knew people were going to ask her how it went. “I came in the door and Jody was very supportive and telling me how proud he was of me and I just put my hand up. He kept telling me how proud he was of me and then I said that he was looking at the new Forged in Fire champion. At first he just looked at me with a blank stare and I repeated that I was the champion.”