10 minute read

The Fighting Editor

The Fighting

Editor

By Logan Kirkland

t was Sept. 30, 1962 and death threats rolled in

Imoments after the Delta Democrat-Times landed with a thud on Greenville’s front porches. The reason: A fiery editorial calling for Gov. Ross Barnett to be tried for sedition for his efforts to block integration at Ole Miss, where his inflammatory rhetoric would help trigger a riot that very night. That day, 10 percent of the paper’s subscribers canceled. Editor Hodding Carter III had threats before but he took these seriously. That night, he lay in the dark with a deputy sheriff and a family friend, waiting for the armed thugs they feared would come. “We went out there to the entrance of the property off of Highway 82 and sat out there with guns behind the brick posts, waiting for them to come,” Carter recalls. “We stayed up virtually all night and nobody came.” Nonetheless, his father, who had won a Pulitzer Prize for editorials on race, mother, brother and uncle raced through the night from New Orleans to Greenville, arriving as the sun came up. By then, Ole Miss was occupied by federal forces. The Carters, exhausted, fell into bed. The next night, a flaming cross was planted on their front lawn. It took courage to take on segregation in the 1960s, when the race baiting rhetoric of segregationist politicians such as Barnett whipped the state into a frenzy and helped resurrect the Ku Klux Klan. At the Democrat-Times, easily the most liberal paper in Mississippi, it wasn’t pretty. Death threats. Area-wide circulation boycotts. A drive to fund a rival newspaper. The Legislature censured the elder Carter. All they got back was a mocking editorial summarily censuring the legislature by a vote of 1-0. Through it all, the Carters held firm. In the end, their newspaper even prospered. They showed how a courageous paper can stick to principles under enormous economic pressure and still survive. They showed how a newspaper can change a town and, sometimes, a state. It helped that both father and son were natural fighters. But it was never easy. “I had a gun in every damn place I could have a gun. One in an office drawer, one in the car, one in about three rooms in the house and in my pocket,” Carter said. For a while, there were rumors that Klansman Byron De La Beckwith, later convicted of killing NAACP leader Medgar Evers, was out to get Carter. “Whenever I sat at the table with a glass window behind me, I had that sense that right now, he could take us out,” Carter said. Sometimes the pressure was more subtle. “There were guys who would not shake hands with me. They would move across the room to avoid having to speak with me in public and on social occasions.” W hen Hodding Carter III left Greenville for Princeton, he had no desire to return and take over the newspaper. He had no desire to be known as “Little Hodding.” He never liked being called the son of a “nigger lover” on the playground, either. After the Ivy League, after the Marine Corps, his father said something that changed his mind. “Look, I have not been fighting all these years simply to watch my family walk away from this product,” the younger Carter recalled him saying. “At least give it a shot.” Carter returned to a paper that was already under a White Citizens Council boycott because it dared to suggest that Mississippians should peacefully comply with a U.S. Supreme Court order to integrate the schools. The Delta fairly bristled with racial tension. Any deviation from the gospel of segregation could bring immediate repercussions. Fearful of damaging the family business, Carter decided “to walk a very careful path” in his early years. “It isn’t to say that I was silenced entirely from my views,” he says now. “But I sure as hell wasn’t going much beyond what seemed to be possible.” When Barnett began his long, defiant stand against court orders requiring Ole Miss to integrate, Carter could restrain himself no longer . He began to shed the paper’s more moderate editorial voice and let loose with stronger opinions blasting the state’s racist attitudes. The Barnett editorial the day of the riot is just one example. “It was just gassed off and all white hot fury,” Carter says now. In the months to come, “virtually everything I was saying and doing was a red flag in front of a bull.” Like his father, Carter had his most fun writing editorials, swinging as hard as he could and saying, “To hell with it.” “A lot of my editorials were not meant to persuade the unpersuadable,” he said. “They were meant to hit them in the head.” And he would have plenty to write about. In 1963, Beckwith shot and killed Evers, the state’s NAACP field secretary. In 1964, the Klan killed three young civil rights workers and buried them in an earthen dam near Philadelphia. Through those turbulent times, Carter lived “a schizophrenic life. By then, I was running the news and editorial sides and at the same time, I got involved in organizations to try to break the stranglehold of the all-white Democratic Party.” Meanwhile, the Citizens Council boycott had taken its toll. The paper had lost much of its circulation outside of Greenville and Leland. The Citizens Council tried to pressure subscribers to cancel. Never subtle, their voices could be heard all over the Delta. “You can’t take that paper.” “You

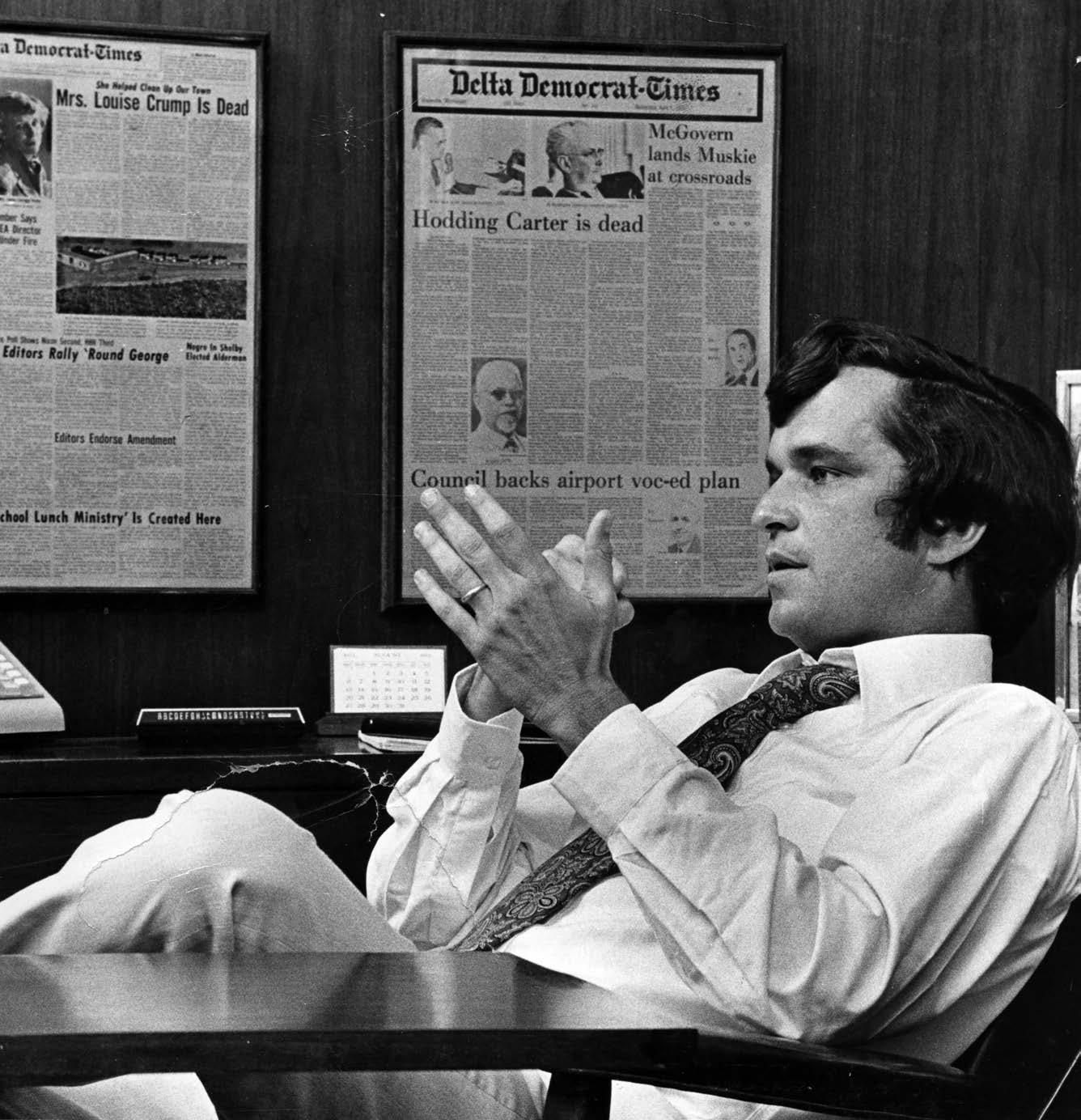

Hodding Carter III is in his office at the Delta Democrat-Times in the early 1960s. COURTESY OF HODDING CARTER III

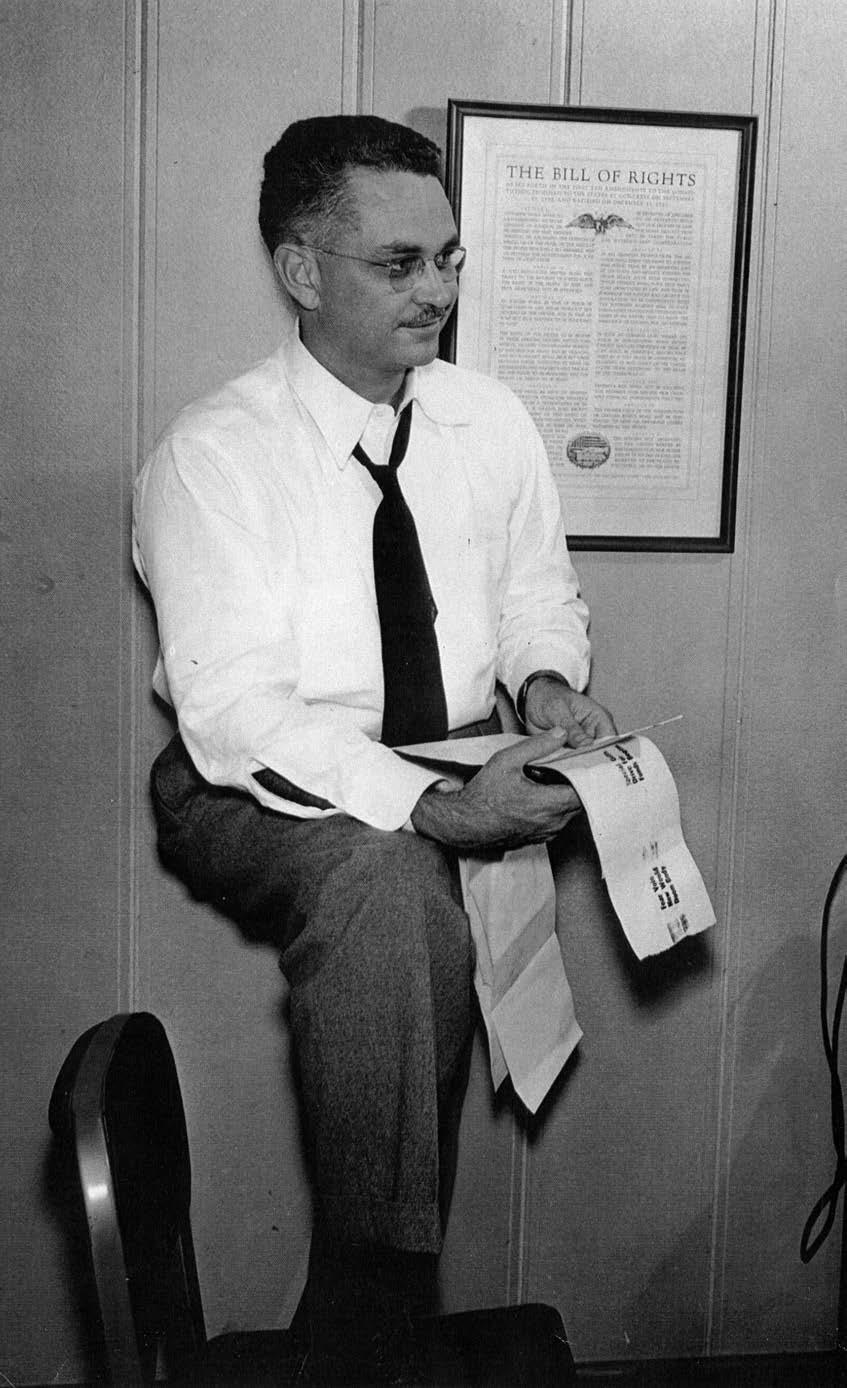

Carter’s father, Hodding Carter II, won a Pulitzer Prize for editorial writing. COURTESY OF HODDING CARTER III will not.” “This is that son of a bitch…” Businesses did not stop advertising, but some cut back. Advertisers would sit down with the young editor and say, “Hodding, we can’t continue to advertise if you keep up this kind of stuff.” Carter, always a talented talker, would patiently explain that the paper was the best way to reach customers in Washington County and that it had the best market penetration in the state. And he kept on writing. Soon, others at the newspaper would feel the heat.

Fresh from Columbia Journalism School, Foster Davis arrived in Greenville with a pleasant smile, eager to work. Black churches were being torched in nearby Indianola. Carter sent Davis to see what was happening. He returned to the newsroom four hours later. He was covered in blood, his shirt was torn. He sported impressive bruises. The rookie had been interviewing people when some locals asked if he was a civil rights worker. No, he replied, I am a reporter for the Delta-Democrat Times. “They jumped me and beat the hell out of me,” Davis said. “Is it okay to fight back?” “For God’s sake, of course it’s all right to fight back,” Carter said. “It’s OK with me if you take a gun, OK. I mean you cannot allow those bastards to get away with this.” After that, Carter said, “he got in more goddamned fights by people challenging his manhood and everything as a reporter for the Delta DemocratTimes and he beat their ass every time.” (Davis would go on to become managing editor of the Charlotte Observer and his paper would win a Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the Jim Bakker televangelism scandal.) As the civil rights movement grew hotter, Carter’s activism increased. “By the middle of 1964, I wasn’t able to restrain myself in traditional newspaper ways,” he said. He became heavily involved in Democratic Party politics to try to bring black people into the all-white party. In 1964, Carter had covered NAACP leader Aaron Henry’s Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and its efforts to challenge the all-white state Democratic Party structure at the party’s national convention. Carter later joined with Henry’s Loyal Democrats of Mississippi, which got seated at the 1968 Democratic

National Convention, paving the way for an integrated party and helping change

the face and tone of Mississippi politics. There he was on television, in the company of Henry and Fannie Lou Hamer, fighting for fair treatment for black citizens and attacking the white political establishment. Through it all, the newspaper weathered the storm. By the end of 1960s, the boycott had finally lost its steam, though the Citizens Council still officially maintained it. It helped that Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The black vote changed everything. “You suddenly weren’t hearing ‘nigger’ anymore off the stump from people running for statewide office,” Carter said. Historians tend to stress Carter’s racial activism. Often missed are a couple of secret weapons that helped his newspaper survive. Arguably, the paper covered civil rights more thoroughly than any other paper in the state. But it also covered Greenville thoroughly, digging into every corner of black and white community life. It was hard for government agencies, from city council to school board to levee board, to escape the scrutiny of the paper. “We were very big on holding the mirror up to Greenville.” The DD-T, as it was affectionately known, was also one of the town’s biggest boosters, an important and influential part of the business community and a primary reason for Greenville’s progressive reputation, so cherished locally. “That’s another thing that saved us,” Carter said. “We may have been crusaders on the side of race, but we were unabashed boosters for the community of Greenville.” It helped that downtown Greenville was not just run by WASPs. “Jews and Lebanese and Catholics,” Carter said. “And while none of them was what I would think of as an integrationist, any number of them knew that if you bring down the Carters, who’s next? … They may have disagreed with us on occasion, but they never abandoned us.” The Carter family was deeply intertwined with the community socially and politically. “I can’t remember what I didn’t join,” said Carter, who required reporters to join a civic club to get to know the town and its people better. As a result, many who despised his politics and editorials accepted him as a social friend and a partner in the joint enterprise of moving the town forward. When the civil rights movement wound down, Carter hungered for more action. He left Greenville to become State Department spokesman under President Jimmy Carter. On Jan. 19, 1979, the shah of Iran, a brutal leader supported by the United States, fled the country. The U.S. gave the shah sanctuary, infuriating the new revolutionary leaders of Iran.

In November of that year, hundreds of Iranian students overran the American embassy and took 69 hostages, holding 52 of them until January of 1981. For two years, Americans helplessly watched the crisis unfold, growing more frustrated by the day. Hodding Carter faced the cameras and the press at tense daily briefings. He quickly became a media sensation for his smooth handling of an aggressive press corps. By then, Greenville was proud of him. “A lot of those people who cussed Hodding way back then would be glad to have him back today,” says former Mississippi Republican Party Chairman Clarke Reed, who credits the DD-T with fair coverage that helped the state GOP gain traction so that it could eventually dominate what had long been a Democratic stronghold. Now, from the green campus of the University of North Carolina, where he lectures on public policy, Carter, 79, looks back on those years with great pride.

— CLARKE REED

Except for that long ago night when a cross was burned on his lawn. He is awfully glad he was asleep and that it did not come down to a gunfight in the dark. “People would have been killed, because we were itchy,” he said. The cross burners turned out to be teenagers “who, having listened to their parents, decided they owed it to ‘our way of life’ to go burn a cross,” Carter said. “I shudder when I think of killing teenagers. My God, because they were too stupid to understand what they were doing. I was very glad they weren’t out there.” Since his newspaper days, Carter has won awards for a critical TV series about the media, graced many a Sunday talk show from Washington, run the wealthy Knight Foundation and become a college professor. None of it compares to his time at the Delta Democrat-Times. It was, he said, the greatest gift an adult could receive, “which was to be a participant in the last good war in American history.” Design by Madisen Theobald

JIM ABBOTT