4 minute read

gettin' round to Restoration

Glimpses of Round Island, three miles offshore of Pascagoula, Miss., have stirred human imaginations since the days before ships sailed the Mississippi Sound. There is much about this island’s cultural and social history that is well known, but other aspects, like its recent geological history, are a bit less defined. The recent preservation of the Round Island Lighthouse is a tribute to this image and how a community can pull together for an iconic cultural resource. Imagination may be even more important in developing support for less visible resource goals, such as restoration to offset the slow, but relentless, forces that endangered the lighthouse in the first place. Those are the rising seas and accelerating erosion that still threaten the last remnants of the island itself.

When managers at the Mississippi Department of Marine Resources (MDMR) assessed water depths (bathymetry) around Round Island in 2010, it became clear that its recent geologic history chronicles a significant transformation of shape and size. It is sometimes noted that Round Island isn’t round, but, based upon historical information beginning around 1700, she likely never was. Rather, think about a large backward capital “L” shape and a much larger one. Using an estimated sea level rise (SLR) rate of 1 ft per century, MDMR evaluated the island’s historic footprints over time. The 300-year-old shoreline, for example, would correspond to the 3-foot depth contour on modern navigation charts. This contour traces the distinctive backward “L” far outside the present-day shoreline, showing the island has diminished from 800 acres to barely 20 acres through erosion and submergence. What remains unclear is how much the historic upland contours of the island affected its change of shape due to sea levels and how much was directly caused by erosion. This balance of coastal change over time is mirrored all along the shorelines and barrier islands of the Mississippi Sound. However, the loss of acreage for Round Island is exceptionally high compared to similar islands in the Mississippi Sound, including Deer Island near Biloxi and Isle Aux Herbes near Coden, Ala. This high loss rate prioritized the island for restoration at the largest scale possible in the context of cost and regulatory requirements and ultimately led to a restoration target of the 300-year-old island footprint.

Round Island’s dramatic transformation may have been triggered by the hurricane of 1717, which is reported in historical accounts as separating Petit Bois Island from Dauphin Island, allowing a new breach or pass for wind and wave energy to enter the sound southeast of Round Island. The maps and charts of this period were generally inaccurate. One of the best early maps that depicts Round Island in any detail, the 1732 map below, still has significant errors. While this map clearly illustrates “Isle Ronde” as a reverse “L” (circled), this map doesn’t indicate the breach in Dauphin Island with Petit Bois that should have been present. However, the overall shape of “Isle Ronde,” as depicted here, helps confirm that the shape estimated through comparison of SLR and modern navigation data was reasonable.

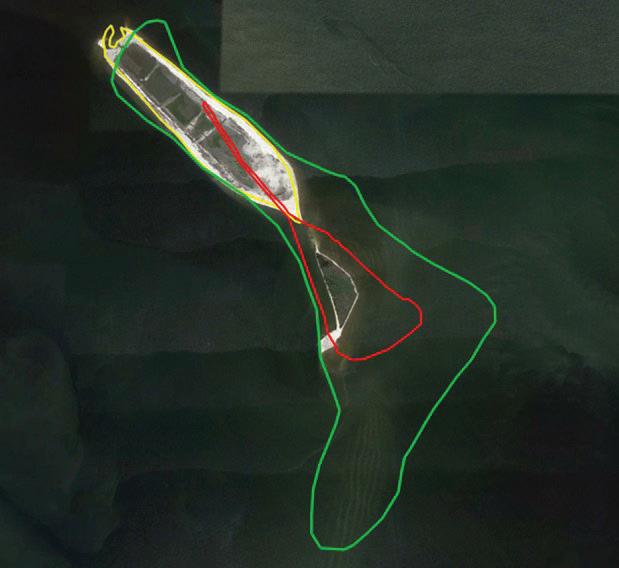

Regardless, the island began to change, retaining its “L” shape at 800-acres around year 1800 on the next image (green line), then rapidly shrinking to a “tadpole” of about 130-acres by 1900 (red line). This 2022-based image also illustrates the remaining 20-acres of original island (inside the red line) and the New Round Island restoration project (bordered by the yellow line).

Restoration at this scale grew out of MDMR’s early 2000 efforts to build a beneficial use (BU) of dredged material program to leverage the enormous resource value of materials being dredged for navigation and development. Recycling these materials is the most basic step toward strategic management of the shorelines and islands that form our coastal estuaries and protect our communities. It is also the most ecologically and financially sound way to offset broader impacts of dredging, such as bank erosion, altered hydrology and barrier island erosion. Though dredging is an essential part of modern society, like maintaining highways, these broader impacts are not traditionally offset except through effective BU programs.

Initially, restoration implementation at Round Island had an advantage because its historic footprint rests almost entirely on sand shoals. This sand could be efficiently moved to the edges of the shoals to form berm, protecting dredged materials placed inside while marsh and other habitats developed. Typical BU projects require sand or rock to be imported at great cost to provide this type of protection and meet environmental regulations. The permit for New Round Island was issued to MDMR in 2013. It was funded by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation through the Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality in 2016. The berm was completed to its 220-acre perimeter in time to receive over 3 million cubic yards of material pumped in from the Pascagoula Ship Channel by the Mobile Corps District (Corps). The Corps and Port of Pascagoula covered the cost of delivering this material, saving about 30 million dollars compared to ocean disposal. The project has survived direct impacts from major storms, particularly Nate in 2017, and its habitats continue to develop and thrive (see below image). The recent incorporation of the original island into state ownership in the Coastal Preserves program will now enable the rest of the 800- acre footprint to be restored in time.

The need for these projects is high. Mississippi loses over 200 acres annually and has dredged enough material in a single year (over 15 million cubic yards) to have supported 1,500 acres worth of restoration. However, restoration by all state and federal partners is averaging well under 50 acres annually and significant amounts of dredged materials are still being discarded. Projects like New Round Island with its unique historic basis, and on-site sand, are an exception. Mississippi’s BU efforts will need broad public support to continue developing projects which leverage natural materials and processes to keep our dredged materials “in the system” to support our natural resources.