SHATTERED LIVES:

The Palestinian children receiving care at MSF’s reconstructive surgery hospital ACTION ON MALNUTRITION: Updates from Sudan and northern Nigeria

The Palestinian children receiving care at MSF’s reconstructive surgery hospital ACTION ON MALNUTRITION: Updates from Sudan and northern Nigeria

MSF’s commitment to speak out against injustice and to advocate for those who need access to healthcare was drawn on repeatedly in 2024.

13

Cover: Karam, 17, survivor of an Israeli airstrike on his home in Nuseirat refugee camp in central Gaza, during a physiotherapy session at MSF’s reconstructive surgery hospital in Amman, Jordan. © Moises Saman/Magnum Photo

Médecins Sans Frontières is an international, independent, medical humanitarian organisation that was founded in France in 1971. The organisation delivers emergency medical aid to people affected by armed conflict, epidemics, exclusion from healthcare and natural disasters. Assistance is provided based on need and irrespective of race, religion, gender or political affiliation.

Today Médecins Sans Frontières is a worldwide movement of 24 associations, including one in Australia. In 2023, 138 Australians and New Zealanders filled roles in our medical humanitarian projects.

Médecins Sans Frontières Australia acknowledges the Gadigal of the Eora nation, the traditional owners of the land on which our office is located. We recognise their ongoing custodianship of land, waters and culture. We pay our respects to Elders past and present.

Call 1300 136 061

Email office@sydney.msf.org

msf.org.au

facebook.com/MSFANZ

@msf_anz

@MSFAustralia

Yet the collective humanitarian response failed to scale up adequately to meet the needs of people facing life-threatening malnutrition – especially children in Sudan and Nigeria. What does 2025 hold?

A year ago, our small clinic in Zamzam displaced people’s camp in western Sudan, where MSF was the only operational healthcare provider for the estimated 300,000 people living there, was overwhelmed by high numbers of malnourished patients in a severe condition.

The health situation for people in Zamzam had drastically deteriorated since the onset of war in April 2023, due to reasons including the withdrawal of international support for food, healthcare and clean water, and lack of safe movement, meaning people could no longer grow food.

The rapid nutrition and mortality assessment that we launched in response showed that 23 per cent of children under five in Zamzam camp were either moderately or acutely malnourished, well above the emergency threshold of 15 per cent. An additional 40 per cent of pregnant and breastfeeding women were also acutely malnourished. We calculated that at least one child was dying every two hours in Zamzam camp.

This shocking data led us to call for the UN to return urgently to North Darfur to coordinate a rapid scale-up of the humanitarian response. While the call resonated with international media, we did not see a material response. Instead, Sudan’s warring parties deliberately blocked aid, and the UN and wider humanitarian community seemed unable to secure access by any means.

By August 2024, with the evidence of MSF’s data, the international and independent Famine Review Committee concluded that famine conditions were prevalent in Zamzam. But aid supplies continued to be blocked by warring parties, at one time resulting in MSF closing outpatient care for 5,000 acutely malnourished children.

We have deep concerns that hunger is being used as a weapon of war.

When the Geneva Conventions were established in 1949, they were meant to protect people in war, to find the humanity in a moment of brutality. What we are finding now, however, is that water, food, and the provision of medical care are increasingly being weaponised. Combatants cut people off from their food supply, pillage healthcare facilities, and fail to ensure a proper supply of water. The majority of people impacted by this brutal treatment are women and children.

My colleague, Dr Tammam Aloudat, who represented MSF at the United Nations General Assembly event on the emergency in Sudan in September, said: “The cost of inaction is already unbearable. It can be measured in the tens of thousands of lives lost and the millions of lives that are on the line as we speak.”

The cost of insufficient action was also worn by communities in northern Nigeria throughout 2024, where humanitarian support had been in dramatic decline.

Even though there are catastrophic levels of malnutrition and recurrent outbreaks of preventable diseases in the northeast and northwest, international organisations and donors have largely disengaged.

Between January and August, we reported a 51 per cent increase in admissions of children with severe malnutrition to our inpatient therapeutic feeding centres compared to the same period the year before. Measles and malaria were also contributing to children’s poor health, and death. (Read more about the recordbreaking malnutrition crisis in Nigeria from page 6.)

We have deep concerns that hunger is being used as a weapon of war.

The needs are extensive: rapid scale-up of malnutrition treatment and monitoring, supported by basic healthcare; consistent implementation of routine vaccinations; food, water and sanitation.

As we move through our days, these are things that we take for granted, but shouldn’t. The fact that we can feed our children properly when they are hungry, the ability to see a doctor when needed and the vaccinations that prevent unnecessary deaths are, sadly, a privilege, when they should be a right.

Based on data we’ve collected in Katsina in the northwest in collaboration with state health authorities, MSF is now extremely worried that the region may fall into phase 5 food insecurity (famine) this year if no additional aid is provided.

Meanwhile in Darfur and Sudan more widely, indications are that the malnutrition crisis is only going to intensify as war drags on. In 2025 we will continue to stand in solidarity with people in north Darfur and northern Nigeria, and push the limits of what MSF can do.

I know—all of us at MSF know— that you will be standing with us. In this world where it feels increasingly as if people are backing away from one another and pitting themselves against one another, your support is an act of care for which we are always grateful.

A recent report, We are Calling for Help, reveals that MSF treated an alarming number of victim-survivors of sexual violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo over the last two years. Our teams supported more than 25,000 people with sexual violence care across five provinces (North Kivu, South Kivu, Ituri, Maniema and Central Kasai) in 2023; and we supported 17,363 survivors in the province of North Kivu alone in 2024 up until May.

The conflict between the M23 group, the Congolese army and their respective allies has been raging in North Kivu province since late 2021, forcing hundreds of thousands of people to flee.

The vast majority—91 per cent—of victim-survivors were assisted in this province, mostly in displacement sites surrounding the capital, Goma.

In addition, 98 per cent of the patients treated were women and girls. The report details that women are not safe anywhere in these displacement sites, whether they are collecting firewood or water, working in the fields, or sleeping in their shelters. Women shared experiences of sexual exploitation in a context of scarce food, water and income-generating activities, where they were tricked or forced into sex in exchange for ways to support themselves and their families.

MSF is treating more than two victim-survivors of sexual violence every hour in the DRC.

This is the highest number ever recorded by MSF in the country.

Since early 2024, MSF has been working alongside volunteers from Arizona-based non-profit groups to provide care for migrants and asylum seekers crossing the US-Mexico border into Arizona via the Sonoran Desert.

Thousands of migrants and asylum seekers cross this route every year. The route is remote, crossing rough terrain where the weather can be extreme; there are no shelters or basic services, and the nearest hospital is several hours away. MSF is helping to identify people’s needs, boost supplies at sanitation and hydration points, and supporting with basic wilderness first aid.

Deterrence and enforcement-focused policies, practices and regulations are ineffective and drive asylum seekers to risk their lives and health to access protection at the US border.

MSF launched an emergency project in September in response to catastrophic flooding in Noakhali district, southeast Bangladesh, helping the Bangladesh Ministry of Health to assist the hundreds of thousands of people displaced.

Our teams focused on addressing urgent medical needs caused by widespread water contamination and damage of local infrastructure. At Noakhali General Hospital, where the MSF medical team saw increased numbers of patients with acute watery diarrhoea, we established an adult diarrhoea treatment ward as well as a triage system to prioritise the most urgent patients.

We also recruited additional staff and ran health promotion sessions at the hospital to raise awareness about hygiene and disease prevention.

One of the worst maternal and child health emergencies in the world is unfolding in South Darfur, Sudan, said a report released by MSF in September. Pregnant, birthing and postpartum women, as well as children, are dying from preventable conditions: between January and August 2024, in just two MSF-supported hospitals in South Darfur, the number of maternal deaths was more than seven per cent of the total number of maternal deaths in MSF facilities worldwide in 2023. A screening of children for malnutrition also revealed rates well beyond emergency thresholds. The health needs far exceed what MSF can respond to.

On releasing the report, MSF called on the United Nations to act decisively and mobilise a response with all available resources to avoid further loss of lives. A coordinated international response is urgently needed, supported by robust funding and unyielding pressure on warring parties in Sudan, to avert mass starvation and suffering.

In Kabirhat Upazila, MSF distributed 1,000 relief item kits including mosquito nets, hygiene products and other essentials, and in Noakhali and Feni districts we disinfected over 1,300 deep tubewells and provided training for 45 local volunteer teams on disinfection to help ensure safe drinking water for the communities.

MSF is calling for unrestricted humanitarian access to Darfur.

Between 5 September and 4 October, MSF treated 1,946 patients for acute watery diarrhoea at the Noakhali General Hospital.

Farah Tanjee

Following alarming developments in the medical-humanitarian situation in northern Nigeria in 2022 and 2023, an even grimmer picture unfolded in 2024. Admissions of children affected by acute malnutrition in some nutrition centres doubled compared to the previous year. We look back on how the crisis unfolded, and the role of MSF in supporting communities east and west.

The past year has been catastrophic for many communities in northern Nigeria, where MSF runs some of our largest therapeutic feeding programs. Inflation, food insecurity, insufficient healthcare infrastructure, disease outbreaks worsened by low vaccine coverage, ongoing conflict and instability and climate shocks have all contributed to an escalating malnutrition crisis.

Aisha brought her acutely malnourished son to the MSF-run inpatient therapeutic feeding centre (ITFC) in Gummi in the northwest state of Zamfara in March: “I got information from people around me, I did what a mother has to do when her child is sick. [At first] I used traditional medicine to treat my son, but thank God for this facility. I’ve seen malnourished children back home, some are brought to the hospital, but some parents […] don’t have time to travel. Insecurity here is really bad. We are not at peace as we hear attacks taking place close to us.”

Established in Gummi General Hospital in 2022, the ITFC has 40 beds and is the only centre for severely malnourished children with medical complications for the estimated 300,000 people of Gummi.

For MSF’s teams, it soon became evident that Aisha and her son were part of an unprecedented surge in nutrition-related consultations and admissions for care in multiple northern states east and west, with more children arriving in a severe condition than the year before.

By the end of August, ITFC admissions recorded by MSF’s teams in Zamfara from January were 65 per cent higher than the same period in 2023.

Yet in the northwest, the level of humanitarian support overall available to respond to people’s critical needs continued to decline. While MSF does not rely on governmental or institutional funds for its activities, this is not the case for most aid organisations in the region, which faced reductions in their already limited funding streams.

In Zamfara this affected the provision of crucial therapeutic and supplementary food: therapeutic food for inpatient and outpatient care of severely malnourished children, and supplementary food for children with moderate malnutrition.

Both types of food were completely unavailable for the first four months of the year and were only supplied in low quantities after that. This seriously undermined the effort to address acute malnutrition earlier in its progression, and therefore avoid exposing children to a higher risk of death or developmental and health problems longer-term.

As Dr Simba Tirima, MSF country representative in Nigeria, explained: “Reducing nutritional support to only severely malnourished children is akin to waiting for a child to become gravely ill before providing care. We urge donors and authorities to increase support urgently for both curative and preventive approaches, ensuring that all malnourished children receive the care they desperately need.”

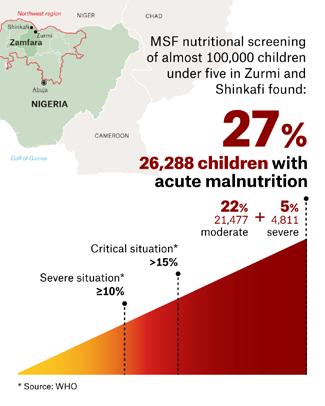

In Shinkafi and Zurmi, also within Zamfara state, one out of every four children under the age of five was acutely malnourished according to a mass screening conducted in June by MSF and the Ministry of Health.

Of the 97,149 children screened in 21 different urban and rural locations, including internal displacement camps, 27 per cent were found to be suffering from acute malnutrition, with five per cent among them experiencing severe acute malnutrition.

The vicious cycle of malnutrition and infection

Alongside the significant increase in malnutrition admissions, our teams were also seeing high numbers of children with vaccine-preventable diseases such as measles. Without reliable healthcare and nutritious food, a weakened immune system means infections make a child more prone to malnutrition, and a child who becomes malnourished is more likely to suffer an infectious disease.

“When I first brought my son into the hospital, I didn’t know if he would survive,” said Hafsat Lawal, whose son Saifullahi was being treated for severe malnutrition and complications in the MSF-run ITFC in Zurmi’s general hospital in late May. “Back at home, because of the insecurity, we don’t have food. The price of food has more than doubled. If we had money, we would have bought some grains, but we cannot.”

Global response shortfalls in the northeast

Meanwhile in the northeast in Borno state, people’s nutrition and lives continued to be disrupted by insecurity, displacement, inflation and inadequate healthcare. Although the UN humanitarian response plan ensured greater attention on the acute needs in Borno and neighbouring Adamawa and Yobe states, the funding shortfall and complex environment remained significant limiting factors for an effective response.

MSF too faced stretched supplies and human resources as we intensified our efforts to respond in ITFCs and outpatient programs closer to dispersed communities.

In April, MSF’s team in Maiduguri admitted 1,250 children to the Nilefa Keji Hospital ITFC, doubling the figure for April 2023. Forced to urgently scale up capacity, by the end of May the centre accommodated 350 patients, far surpassing the 200 beds initially designated for the conventional malnutrition peak—the lean season between harvests— that was yet to come. MSF activated emergency spillover tents before resorting to treating patients on mattresses on the floor.

By the end of August, ITFC admissions recorded by our teams in Borno from January were 71 per cent higher than the same period in 2023.

Climate change is exacerbating malnutrition around the world, with a disproportionate impact on women and children.

The health of women and their children is intrinsically linked, and especially so when it relates to nutrition. Together, mothers and children become malnourished due to an inadequate diet, disease, and the bi-directional cause-and-effect relationship between the two. There is a range of layered factors that contribute to nutrient-poor diets and illness. At each level, the influence of climate variability and change is increasingly linked to poorer health outcomes for women and children, in the shortand long-term.

Climate affects the foods that are grown and harvested from the sea and land. Changes in climate affect the composition of people’s food, its adequacy and its availability. If families have poor access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food, it is difficult to feed pregnant women, babies and young children well, which hampers their growth. Unhealthy environments become unhealthier due to degraded land and water sources, for example. Warmer conditions promote mosquitos, spreading malaria more easily. If disease proliferates and children do not receive appropriate healthcare, to prevent or treat their illness, the combination of inadequate care and exposure to disease makes it more likely they will suffer malnutrition.

Extreme weather events damage health infrastructure and rupture medical supply chains. Produce markets become more volatile. Without robust economic, political and ideological structures, these risks and their consequences remain unaddressed.

If collectively we fail to allocate environmental, financial, social and human resources, and develop policies, that are not only nutritionsmart but also climate-smart, we will continue to need to treat malnutrition at great cost, some of that sadly counted in women’s and children’s lives.

Cascade effect of climate change

“Climate change and malnutrition are two of the greatest challenges facing humanity today. Malnutrition and climate change are intrinsically interconnected because of the interdependence of climate, ecosystems, biodiversity and human life,” says Samuel Kopi, MSF nutrition advisor based in Nairobi, Kenya.

The vast majority of people living in northeast and northwest Nigeria are subsistence farmers. Yet small-scale farming is an extremely climatesensitive livelihood, prone to severe disruption by erratic rainfall causing drought, or flood.

The cascade effect of prolonged and intense rain leading to food insecurity and malnutrition was writ large in August in Zamfara. According to a flood assessment report compiled by the International Office of Migration, 11 areas were affected—Gummi most seriously—and 47 per cent of the affected population were children under five years old.

Laura Kant, MSF project coordinator, described the devastation in Gummi at the time: “Men, women and children have lost their lives as they drowned or buildings collapsed on them.

and children

An estimated 50,000 people that did survive are left without a home… For people who mostly rely on farming activities, the massive destruction of crops during harvest time means that they have lost their access to foods and income. MSF teams have already witnessed persistently high levels of malnutrition across the northwest of Nigeria and we are concerned that the cases may rise.”

Several weeks later, heavy rains in Borno State caused the Alau Dam to overflow, resulting in significant flooding in and around Maiduguri.

According to Borno State authorities, between one and two million people were affected, with close to 400,000 forced to leave their homes and the majority moving to spontaneous refuge sites. Many healthcare centres, including several supported by MSF, were damaged and rendered inaccessible.

“Admissions to the nutritional facilities had just started to reduce when the flooding occurred,” said Dr Ashok Shrirang Sankpal, deputy medical coordinator for MSF in Nigeria. “With markets and businesses heavily impacted, the harvest damaged and livestock washed away, there is huge concern that the downward trend will reverse, and admissions start to rise again.”

Zainab Mohammed and her three children were among the many people displaced and left without food in the following days. “We couldn’t save anything […] We heard the sound of water flowing into our house and by the time we checked, our house had been flooded. It was difficult finding a way to escape but luckily, we made it out. We trekked for about two hours before reaching the camp,” Zainab explained.

“Here we lacked food until a distribution was organised. We would love to be able to go back home because this place is not a good place to stay. But we don’t have anywhere to go because our houses are still flooded. My children are vomiting and have watery diarrhoea. It’s not clean here, and that I think may be the reason why my children are ill.”

The acute malnutrition crisis and people’s aggravated healthcare needs in 2024 went beyond MSF’s capacity despite our scaled-up response. In 2025, we will continue our calls to ensure adequate support to the neglected north.

Climate change and malnutrition are two of the greatest challenges facing humanity today.

MSF’S NUTRITION PROGRAMS IN NORTHERN NIGERIA, JANUARY - AUGUST 2024:

Recorded 208,702 admissions to outpatient therapeutic feeding centres, (ATFC) representing a 51% increase on the same period in 2023

Admitted 52,725 patients to inpatient therapeutic feeding centres, (ITFC), representing a 60% increase on the same period in 2023.

After more than a year of relentless Israeli attacks on Gaza, over 41,000 Palestinians in Gaza have been killed.

In addition, over 95,000 people have been injured, more than 12,000 of whom are in need of medical evacuation for specialised care. At MSF’s reconstructive surgery hospital in Amman, Jordan, our teams are treating the few Gazan children we have managed to transfer from Egypt to Jordan for rehabilitation.

Right top: Shahed, 16, takes a reading class in the hospital. She is undergoing comprehensive treatment following the amputation of her leg in Gaza. An airstrike on her home caused her injury and killed her father and sister.

Right below: Dima, 11, during an occupational therapy session. The small number of patients receiving rehabilitative care in the Amman hospital is barely a fraction of the number of people in need of this treatment in Gaza. “We know from our experience at the hospital, where we have treated people with war wounds from the region for nearly 20 years, that typically up to four per cent of people who suffer war injuries will need reconstructive surgery,” says Moeen Mahmood Shaief, MSF head of mission in Jordan. This translates to up to 4,000 people in Gaza. However, requests for the medical evacuation of patients have been continuously denied by Israeli authorities.

Ziad, 52, is a psychologist who was working for UNRWA in Gaza. His home was hit by an Israeli airstrike which killed 13 members of his family, including his wife, youngest son Mohammed, and eldest son Tareq. His son Karam (left), 17, and daughter Ghena (right), seven, were severely injured. The impact of the bomb was so severe that the remnants of the house were suctioned into the ground.

An MSF physiotherapist works with Karam. An airstrike caused severe burns to Karam’s face and other areas of his body, as well as a serious injury to his arm. “When Karam was brought into the emergency room [of Al Aqsa Hospital in Gaza], I didn’t notice it was my son,” says his father Ziad. “He had no human features on him. His body was completely black. His eyes were closed.” Karam was in a coma for seven days; staff at Al-Aqsa Hospital performed six rounds of plastic surgery before he was evacuated to Egypt and then Amman.

Dima survived an Israeli airstrike on the home next to hers, despite being buried under the rubble for an hour. “I managed to move my hand and used a cable to signal to people that I was there,” she says. Her baby nephew, who she was holding when the attack happened, has never been found; 75 people were killed including Dima’s eldest brother.

Abdul Rahman has had several surgeries, both in Gaza and now in Amman, to try to restore the function of his leg which was almost amputated following an airstrike that hit him when he was out looking for food for his family. He is staying at the hospital with his mother, but longs to be reunited with the rest of their family who are still in Gaza.

‘We will always come back’

More than 1,900 people have been killed and over 1.2 million forced out of their homes in Lebanon due to bombardments and incursions by Israel, especially in the south. The scale of the displacement surpasses the country’s ability to house people, with many left to sleep on the streets in mid-winter.

MSF has deployed mobile medical teams in Beirut, Mount Lebanon, Saida, Tripoli, Bekaa and Akkar, offering psychological first aid, general medical consultations, medication and mental health consultations. This letter includes testimonies from people in contact with MSF in the south and Beirut.

Hassan Kheir Eddine, 67, received treatment for hypertension with MSF in the southern coastal city of Saida. He and his wife fled Israeli bombings in Kfar Melki, in the south of Lebanon, leaving with only the clothes on their backs.

A retired employee who lost his pension and savings in the 2020 economic crisis, Hassan has been uprooted three times during the recent escalations. “My sons are also displaced, scattered across the country. That alone is a struggle, but what we are going through is similar to what everyone else is.”

He reminisces about the olive harvest and his deep connection to the land he was forced to leave behind. “There is nothing quite like the south. Wherever we go, whatever we lose, and whatever we are offered, we will always come back. I lived through the 1982 Israeli invasion and remember the airstrikes on southern villages then. As we returned to our homes then, we will now.”

Hala, 24, is a Syrian refugee and mother of three—Yamen (two), Rawan (three), and Razan (six). They fled airstrikes in Adloun, south Lebanon.

“We left with nothing. We escaped on a motorcycle, but it broke down here in Saida. My husband went back to retrieve our belongings, but everything was stolen.”

Now, they rely on aid for food. “All my children are sick with vomiting and diarrhoea. Rawan, who has Down’s syndrome, used to receive physical therapy to walk and move. We had high hopes that she would begin verbal communication through speech therapy soon, and she had made so much progress. But now, all that is gone. She requires lots of medications and is often bullied by other children for not being able to express herself.”

Khadija, a Syrian refugee, was displaced from Nabatieh in the south with her five children. They have sought refuge in an open parking lot in Saida with other Syrian refugee families.

“She’s fading right before my eyes,” says Khadija, pointing to her sevenyear-old daughter, who she says suffers from stunted growth.

“We never feel clean,” she says, referring to the conditions they are living in. “People are competing over food here, and we don’t have enough clean water to wash. We go to the sea to relieve ourselves, but there are often men around.”

Her children are battling various health issues and it’s breaking her spirit. “Sidra (13), has asthma, Hiba (seven), weighs barely 10 kilograms, and Malak, my eight-month-old, has a fever and diarrhoea. I breastfeed her whenever I can, but it’s not always enough, and I can’t properly clean her bottles.

“Sometimes I wish we had stayed and died in an airstrike instead of living like this.”

The MSF team spoke with Hassan* on 30 September in Ramleh El-Bayda, Beirut, where MSF has been supporting displaced people in shelters such as schools.

“I come from Nabatieh governorate, in south Lebanon. I used to live with my wife and three children in the southern suburb of Beirut. Four days ago, we decided to leave our home with my family because we were worried about our safety. That night was like a horror movie; warplanes, airstrikes, you name it. While we were in the car, we could feel the ground shaking.

“We spent the first two days in a house in another neighborhood of Beirut but then the owner asked us to vacate the apartment. Now, we are here in Ramleh El-Bayda in Beirut. We are 20 members of my family, stranded on the beach. All shelters and schools are full. Where should we go? We have no place to go. It seems that nowhere is safe now.

“The situation is far worse than anyone can imagine. We have so many needs. When we left, we only took a couple of clothes and our documentation. We couldn’t even bring a mattress or a pillow. Last night, we slept on chairs. No one is helping us.

“All I care about is the kids. The youngest of them is a year-and-ahalf old. How can I look out for my family?”

Um Mohammad, a Syrian refugee woman, speaks with an MSF worker in the Saida parking lot where displaced people are sheltering. © Dalia Khamissy

Christopher Lee

Home: Sydney (Gadigal land)

Christopher’s relationship with MSF started when he worked on a construction project in Liberia. Now, he has chosen to continue the connection as a supporter of the organisation.

During the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone [from 2014-16] I went to a talk given by one of the returning MSF nurses in Australia. It struck me that a lot of the work needed in the Ebola crisis was logistics—because at the time, there wasn’t much you could do medically to treat people.

After that talk, I applied to MSF. My first assignment was to Monrovia, Liberia, in 2015 as a construction supervisor. It was to build a staircase—which sounded rather mundane— but proved both challenging and rewarding!

MSF had converted a three-level building into a children’s hospital, and our job was to design and build a new steel fire escape, with local contractors. Without soil testing or surveying instruments, and no cranes or scaffolding, we had to make do and improvise to achieve a safe and economic result. We painted the finished staircase with brightly coloured cartoon animals matching the names of the different wards (monkey, kangaroo etc.). We were working in and out of the hospital wards, so were quite engaged with the staff and patients. Seeing the sick children and the care they received convinced me of the importance and impact of MSF’s work.

MSF is not changing the entire world— it’s about making a a small but significant difference. I also think MSF’s advocacy work, based on knowledge and experience on the ground, is a very powerful part of MSF’s contribution.

To learn more about our Philanthropy program, please visit msf.org.au/major-donors or contact our team at philanthropy@sydney.msf.org

DR ALICE TWOMEY Paediatrician

Home: Sydney, NSW (Bidjigal and Gadigal land)

MSF experience: Haydan, Yemen, 2023-24

Why did you want to be a part of MSF?

I wanted to work with MSF because the principles resonate with me – that MSF is independent and provides healthcare with impartiality and neutrality.

What are the health needs in Haydan?

I was surprised, being used to working in Australia where most patients in hospital are adults, that in Haydan 90 per cent of our patients were children or newborns. There is limited access to health education, health services, food and clean water due to the remote location of the villages surrounding Haydan. Women and their babies often arrive late to the hospital in quite poor condition having travelled many hours from their homes in the mountains along precarious roads. We see malnutrition, especially in mothers and newborns, sickle cell anaemia with associated complications and high rates of vaccine-preventable diseases like measles.

As the only consultant paediatrician, what did a typical day involve?

Patients across the hospital were cared for by a team of generalist Yemeni doctors; as the only paediatrician I was on call 24/7 – it felt like my days never started or ended. Typically, if I wasn’t in the hospital overnight, the day would start around 7:30am reading the local and MSF news for updates from the last 24 hours. Around 8am I would attend the hospital-wide managers’ meeting or supervise the morning handover – providing advice on patient care as needed.

I would then review any critical patients that had been unstable overnight with my Yemeni medical colleagues. While they did ward rounds I would continue with reviews and updating hospital policies and procedures. Then I would be called to review complex cases in the outpatient department, critical cases in emergency, and critical deliveries of newborns requiring resuscitation.

Essentially, bouncing to any department where I was needed. I also ran teaching sessions with staff throughout the hospital. My checklist for what needed to be done every day would expand and expand so I would often spend the evenings when it was a bit quieter catching up on paperwork and emails. Then I would go home to our accommodation to be on call throughout the evening for any critical or complex patients.

What did you prioritise to improve quality of care?

I recognised that babies weren’t getting appropriate examinations because many of the Yemeni doctors and midwives hadn’t had access to training on how to examine a neonate. The international midwife and I implemented the MSF neonatal examination guidelines so our Yemeni colleagues were able to examine at the first presentation, and prior to discharge, to achieve early recognition of neonatal abnormalities and work towards preventative care.

What was one success from your time there?

While I was in Haydan, an international physiotherapist, Lucille, arrived to train the Yemeni physiotherapist, Zayed, for a neurodevelopmental program that worked to identify developmental delay in children.

I set up a morning multidisciplinary meeting with the Yemeni staff, where Zayed attended the ward to discuss the cases with the doctors and train the staff to recognise developmental milestones in paediatrics and refer for physiotherapy. Zayed really appreciated being able to care for more patients and have his work recognised as more than just putting casts on.

What advice do you have for paediatricians interested in working with MSF?

I really valued going on my first assignment after having several years of paediatric experience, to be at a point where I had developed a skill set to share. Learning from my Yemeni colleagues and being able to share something lasting with one another was a great experience. If you’re thinking twice, don’t! Take the risk. I kept going back and forth with questioning whether or not to go. If I was brave enough. But once I was in Haydan, I knew it was where I was meant to be.

Paediatricians are responsible for all medical care related to children, excluding surgery, in resource-limited settings. They deal primarily with acute cases of malaria, respiratory infections, malnutrition, tuberculosis, and HIV; responsibilities also include training and working with local colleagues to provide support and guidance.

In this recruitment webinar we focused on MSF’s approach to providing paediatric and neonatal care in humanitarian contexts and the clinical challenges for our teams. MSF paediatrician Dr Joanne Clarke and paediatric and neonatal nurse Janine Evans took us through the skills needed to work flexibly alongside multidisciplinary colleagues in lowresource settings, with communities who have experienced epidemics, conflict and disasters.

Watch the recording at msf.org.au/join-our-team/workoverseas/recruitment-events

We are recruiting roles dedicated to improving the quality of care for newborns, their mothers, families and communities— including paediatricians, obstetriciangynaecologists, midwives, and neonatal and paediatric nurses.

Interested? Please apply at msf.org.au/join-our-team

Staff from Australia and New Zealand currently on assignment with MSF.

Salman receives treatment for acute watery diarrhoea at Noakhali General Hospital following the floods in Noakhali district. ©Sarah

This list of project staff comprises only those recruited by MSF Australia. We also wish to recognise other Australians and New Zealanders who have contributed to MSF programs worldwide but are not listed here because they joined the organisation directly overseas.

Afghanistan

Deputy Medical Coordinator

Nursing Activity Manager

Bangladesh

Infection Prevention and Control Manager

Paediatrician

Chad

Finance and HR Manager

Democratic Republic of Congo

Anaesthetist

Epidemiology Activity Manager

Doctor

Ethiopia

Deputy Head of Mission

Greece Midwife

Haiti

Humanitarian Affairs Manager

Surgeon

msf.org.au facebook.com/MSFANZ

@msf_anz

@MSFAustralia

Iraq

Midwife Supervisor

Kenya Doctor

Finance and HR Manager

Kiribati Head of Mission

Medical Coordinator

Project Coordinator

Libya Head of Mission

Project Coordinator

Malawi

Obstetrician-Gynaecologist

Mozambique

Medical Referent

Nigeria

Project Coordinator

Palestine ER Doctor

Head of Mission

Nursing Activity Manager

Personnel Administration Manager

Psychologist

Papua New Guinea

Mental Health Activity Manager

Project Coordinator

Sierra Leone

Project Coordinator

South Africa

Medical Doctor

South Sudan

HR Coordinator

Intersectional Legal Advisor

Midwife Activity Manager

Nursing Activity Manager

Nursing Activity Manager

Operational Deputy Head of Mission

Sudan Hospital Director

Project Coordinator

Medical Referent

Syria

Finance and HR Coordinator

Head of Mission

Yemen

Epidemiologist Paediatrician

Various/Other

Deputy Medical Coordinator

Regional Advocacy Representative