9 minute read

In the Spotlight

Katherine Foss experienced 2020 as the professor who wrote the book on American epidemics and attained major media exposure

story by Allison Gorman and photos by J. Intintoli

Early last year, as it was dawning on Americans that their lives were about to change in some drastic but unknowable way, MTSU’s Katherine Foss got a phone call from The New York Times.

Thus began the steady influx of requests from newspapers, magazines, broadcasters, and podcasters wanting to talk to the woman who wrote the book on epidemics in the United States.

Foss, a professor of Media Studies, couldn’t answer the nation’s pressing epidemiological questions, like how this mysterious new virus spread or who was most vulnerable to it. But she could offer perspective—from comforting to cautionary—on our past public health crises and the narratives that shaped our responses to them.

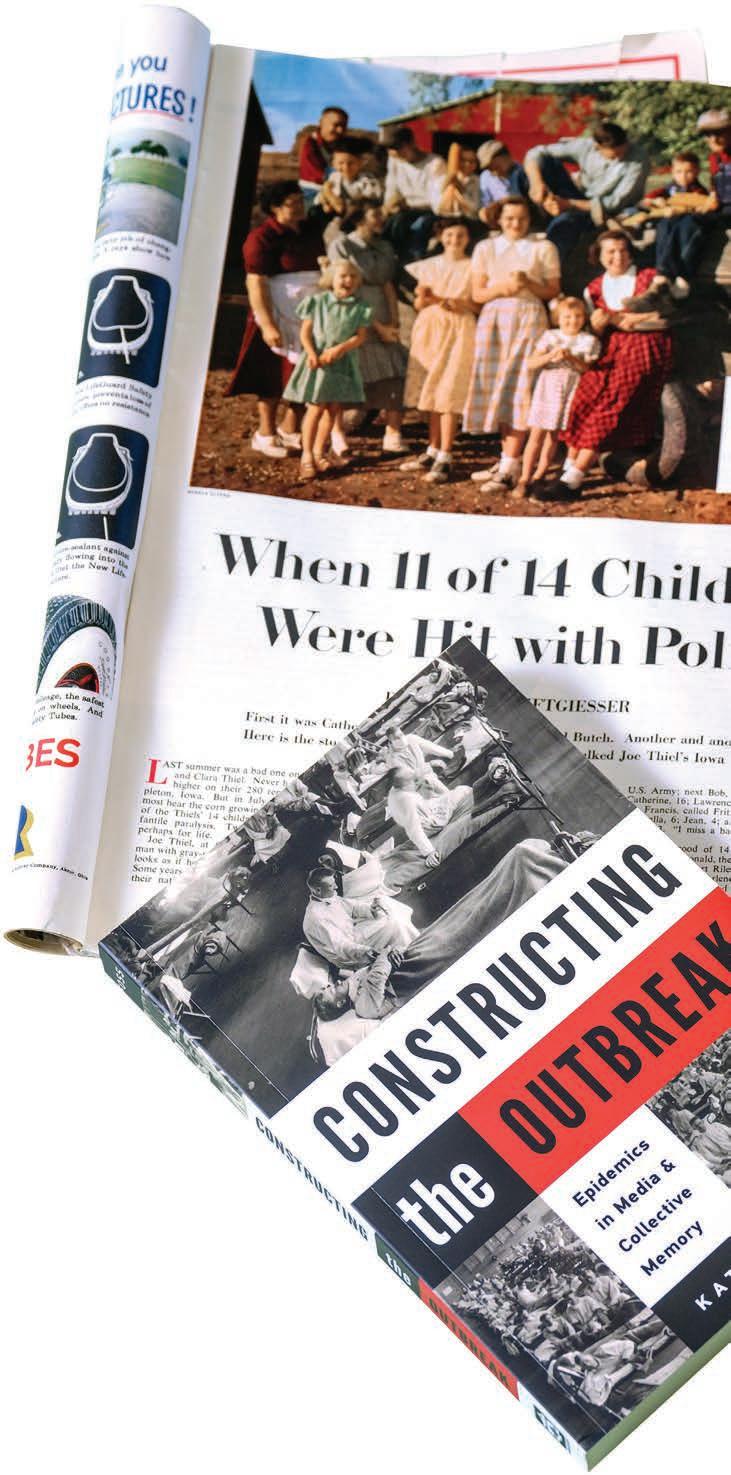

Her 2020 book, Constructing the Outbreak: Epidemics in Media and Collective Memory, revisits scenes from seven inflection points in our country’s public health history—from 1721 in smallpoxravaged Boston, where authorities debated whether to try inoculation, suggested by an enslaved man who had been inoculated in his home country in Africa; to turn-of-the-century New York City, where Irish immigrant “Typhoid” Mary Mallon was the victim of forced isolation and collective demonization; to 1952 in Minnesota’s Twin Cities, where overflowing polio wards reflected a terrifying virus at its peak, even as Dr. Jonas Salk was on the verge of developing a vaccine.

Back in 2016, when Foss decided to write the book, she couldn’t have anticipated that its publication four years later would align with the deadliest epidemic America had seen in more than a century. She says her sudden popularity with the media last year was “a curiosity.” So was living through the kind of event she’d just finished writing about.

Crises and Controversies

Since joining the MTSU faculty in 2008, Foss has carved out a scholarly niche at the intersection of media and medicine in the United States.

Author of three books and editor of three more, she has written extensively about how news and entertainment media shape Americans’ understanding of public health issues and how they serve as “gatekeepers” who frame our collective memory of epidemics and similar crises.

If that sounds like uncontroversial academese, don’t tell that to the World Health Assembly, which in 2018 was shocked when the United States refused to sign its evidence-based resolution encouraging breastfeeding over bottle feeding. And don’t tell it to the two moms in Mora, Minnesota, who that same year unwittingly triggered a national debate by nursing their babies at a local kiddie pool.

Foss waded into those turbulent waters with newspaper op-eds pointing out that the cultural push against breastfeeding in the United States in the early 20th century—and a similar effort later in developing countries—was framed and funded by infant-formula companies, to devastating effect. (She wrote the book on that, too—Breastfeeding and Media: Exploring Conflicting Discourses That Threaten Public Health, 2017.)

Publication of Constructing the Outbreak proved timely for Katherine Foss’ research on past epidemics.

When COVID-19 turned into an American public health crisis, Foss was as blindsided as the rest of us, but she saw the controversies coming. In early January 2020, as worrisome reports about the virus were just making landfall here, Foss’s teaching assistant mentioned that she was trying to find masks to send to her family in China.

“I casually remarked that I just couldn’t imagine that Americans would ever be willing to wear masks—that individualism would prohibit such collective action,” Foss wrote in a blog post later. “I had no idea that we were on the cusp of a global pandemic.”

In early February, roughly three weeks before the phone call from The New York Times, Foss wrote an opinion piece for The Tennessean reminding readers that the flu posed a greater public health hazard to Americans than the new coronavirus.

The piece “became outdated almost immediately,” she said. But it was also prescient. In the op-ed, Foss warned that “misinformation has distorted and impaired flu vaccination efforts” and that a “lapse in the collective memory of infectious disease feeds anti-vaccination rhetoric that undermines public health efforts to curb transmission.”

In other words, time and first-world privilege had eroded Americans’ reasonable fear of contagious illnesses. More than a hundred years after the 1918 influenza outbreak killed 675,000 of us, we had forgotten what it was like to have family, friends, and neighbors felled by a virus in devastating numbers. Yet as 2020 wore on, and COVID-19 was charting a similarly fatal course across the country, many Americans remained dismissive of it. Foss attributes the prevalence of that attitude to two factors.

First, we didn’t feel the collective loss in a visceral way, as we might have a century ago, because media coverage was relatively sterile. There were few visceral images or stories from the front lines of the war on COVID-19. Even the obituaries of victims rarely mentioned cause of death.

Second, Foss said, we had never before had a president downplay the dangers of a deadly virus.

“In the past, no politician who wanted to get elected again would have questioned disease, because it was just too much of a threat,” Foss said. “It was such an ever-present part of life, that could take life away so quickly, that no one was that arrogant in the past.”

Historical Parallels

It was this extreme politicization of a public health crisis in the United States—a situation as novel as the virus itself—that sparked that February phone call to Foss from The New York Times. But the many interviews that followed generally focused on historical comparisons, as people looked to the past to make sense of a bewildering present.

The media’s preferred touchpoint was the so-called Spanish flu, which struck the United States toward the end of what was known then as the Great War, in 1918. The virus took nearly six times more American lives than the conflict did, in less than half the time. Yet in our collective memory, Foss says, it was eventually reduced to “a footnote of World War I.”

Then came COVID-19, and Foss was suddenly on the receiving end of a lot of Spanish flu questions, such as “How did Americans celebrate Halloween in 1918?” (Most cities banned or scaled back celebrations, she told a writer for History.com—although back then Halloween was more of an adult holiday.) She also tried to correct misinformation about how that influenza pandemic played out in the United States. She found little evidence to support the narrative that there were a significant number of “anti-maskers” in 1918; most

Americans were compliant, even though wearing masks to prevent the spread of infection was a new concept then. And she was frustrated by the frequent parallels drawn between “waves” of Spanish flu and COVID-19. The comparison is problematic, she says, because a century ago Americans didn’t have timely information that would have enabled them to adjust their behavior to the emerging outbreak. “That drove me nuts, when we kept comparing COVID-19 to influenza,” Foss said.

SHE COULD OFFER PERSPECTIVE— FROM COMFORTING TO CAUTIONARY— ON OUR PAST PUBLIC HEALTH CRISES.

She thinks a closer comparison would be polio: In the early to mid-20th century, as with COVID-19 in its early stages, no one understood how polio spread or who might succumb to it. Most infected people felt perfectly fine or had only mild symptoms; others were paralyzed or died. In 1937, a late-summer surge in that dreaded disease, which notoriously struck young children, led Chicago Public Schools to develop “radio school,” the original remote learning. Foss wrote about that pioneering moment in American public health for the online news outlet The Conversation.

During the latest pandemic, Foss published many epidemic-themed articles in popular media, from Smithsonian Magazine to The Washington Post. Many of those were syndicated and picked up by other outlets. But the remote-learning piece really struck a chord, garnering 346,000 hits between October 2020 and May 2021.

It’s not hard to imagine parents googling for reassurance, if not answers, as COVID-19 upended a second academic year. The virus was making the logistics of family life nearly impossible, especially for working mothers. Meanwhile, parents of school-age children were tearing their hair out trying to keep them engaged academically. Foss, who has two young daughters, was right there too.

Hands-On Research

There’s a big difference, she notes, between reading about other people’s experiences in epidemics and experiencing an epidemic yourself.

“I obviously prefer the vicarious method,” she said. In 2018,

Foss spent a semester doing research for Constructing the Outbreak. She walked through historic Philadelphia, where yellow fever killed thousands of people in 1793; pored over records of the Minnesota Historical Society in St. Paul; and traveled to New York to visit the March of Dimes Archives in White Plains and the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in Hyde Park. The documents she read inevitably reflected the perspectives of doctors, government officials, and other authority figures.

“What’s not captured [in historical records] is the day-to-day uncertainty of regular people,” she said.

Parenting through a pandemic? That history hadn’t been written.

But now it has, millions of times. In 2020, parents took to social media to document their pandemic moments, from hair-raising to mundane. That included Foss, who found blogging “therapeutic” at a time when she felt like she was failing both her students and her children—who were suddenly her students too.

The same week in March 2020 that MTSU shifted classes online and public schools shut down, Foss received the final proofs for Constructing the Outbreak, which was scheduled for release in September. So while she was figuring out how to teach and parent in totally new ways, she also had to figure out how to work COVID-19 into her completed book, so it wouldn’t be obsolete before it was published.

It probably benefited the book that she didn’t have the freedom to make big changes, she says.

“Even speculating wouldn’t have worked in that moment, because optimistic me, I couldn’t fathom how long the crisis would go on. Part of this was just a way of coping, just thinking, ‘Things will get better.’ ”

Like so many of us, she slogged through. Making weird pandemic purchases. (“Drowning in stress” during quarantine, she bought a rubber boat so her daughters could paddle around their rain-flooded backyard.) Going to heroic lengths to make homeschool fun. (“My kids were not amused when I woke them up dressed like Maria von Trapp on Sound of Music day,” she blogged.) And eventually things did get better—including her book sales.

“I lost money on my first book because I bought copies for my parents,” she remarked. “That put me in the hole.”

Not that selling books has ever been her motivation for writing them.

“Having been an academic for more than a dozen years, I publish a lot of stuff,” she said. “But we don’t write for fame or money. That’s not the business we’re in.”

Nevertheless, Constructing the Outbreak has been doing brisk business on Amazon.

Foss really hasn’t been paying attention, though; she’s planning her next book. The pandemic isn’t over, but Foss says there’s no time to waste. If they’re not contained, memories mutate. She can’t let that happen.