Monmouth University

September 3 - December 20,

Monmouth University

September 3 - December 20,

I Wish to Say

Monmouth University

September 3 - December 20, 2024

Curated by Corey

Dzenko

Statement from the Gallery Director

Monmouth University’s Center for the Arts and the Department of Art and Design are pleased to present I Wish That I Had Spoken Only of It All: Twenty Years of Sheryl Oring’s “I Wish to Say” this fall in the DiMattio Gallery. This very important retrospective exhibition will showcase the culmination of Oring’s 20-year project and related works created from 2004 through 2024. Over the years and with a range of interactions and installations of I Wish to Say, Oring has certainly demonstrated in a profound way that, yes, indeed, “The pen (or perhaps the typewriter) is mightier than the sword.” Oring invites all who visit the exhibition to share their thoughts, expectations, hopes, and dreams with the incumbent president. This exhibition will provide for a wonderful opportunity for the Monmouth University community and patrons from near and farther away to visit and contribute to the tremendous body of work that this project has generated. At such a compelling time to in our nation’s history, what an opportunity for us all to participate in this dynamic exhibition!

Scott Knauer, M.F.A.

Director of Galleries and Collections

Monmouth University

Statement from the Department Chair

The lonely, tortured artist producing intense and timeless works abstracted from the world in an isolated garret, only belatedly accepted by a skeptical public. How romantic. Sheryl Oring upends these quaint tropes with art events that are performative, engaged, and contemporary. The setting for her I Wish to Say is a public one, and the occasion the quadrennial nail-biters that are US presidential elections. Her goal in typing (on a typewriter!) the dictated words of participants onto postcards, which are then sent to the president, is to give voice to those usually unheard, thereby affirming a commitment to the free expression of ideas in an age when the internet allows even the most fevered, fantastical distortions of reality to see the light of day. In our current electoral cycle, only a scant few weeks ago turned upside down, the voices of ordinary citizens expressing common sense in a community setting seems a healthy, grounded counter to the slick media hoopla all around us. Monmouth University and the DiMattio Gallery are proud to host this timely reminder of the enduring power of democratic expression. The essence of art.

Fred McKitrick, Ph.D.

Chair of the Department of Art and Design

Monmouth University

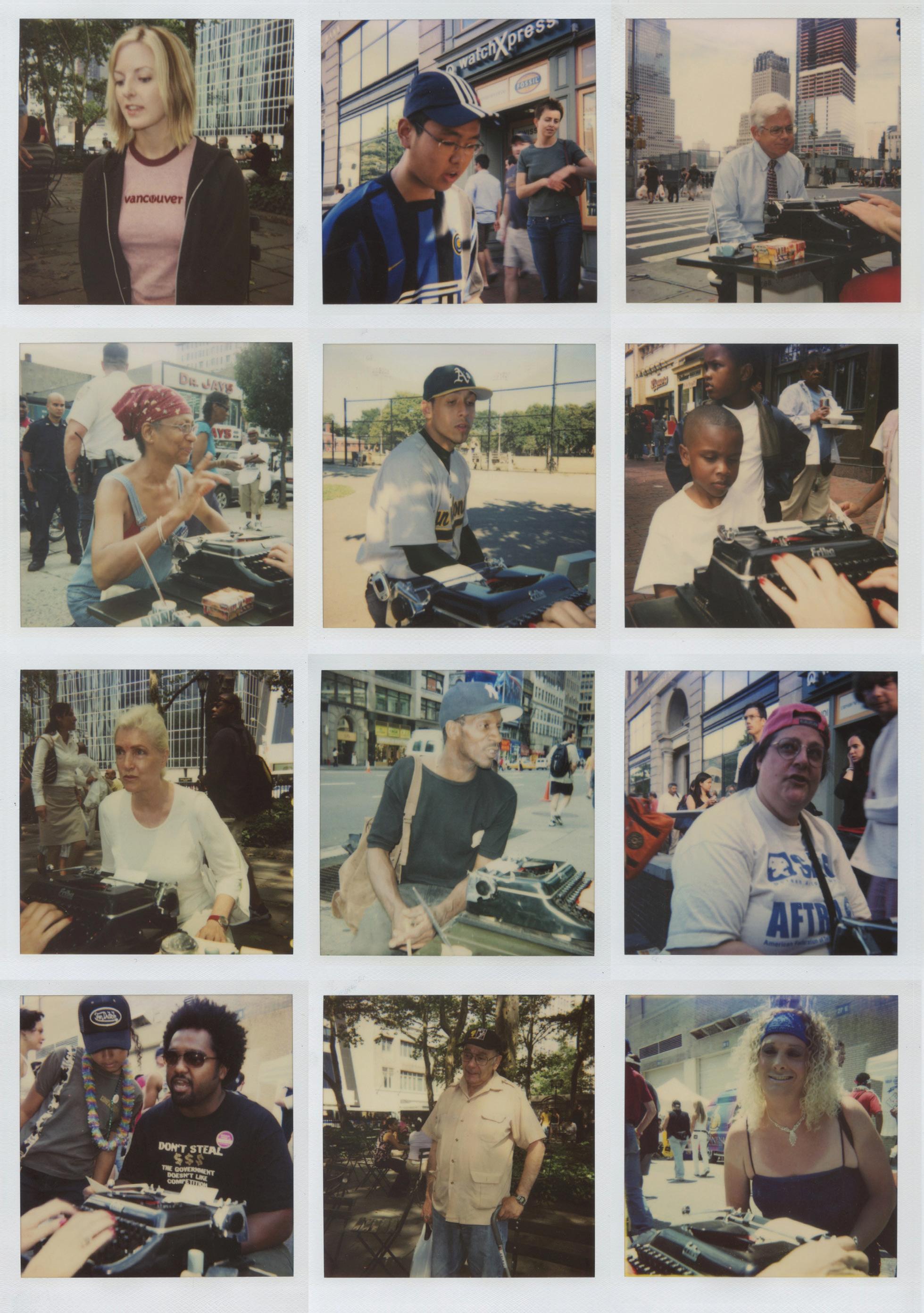

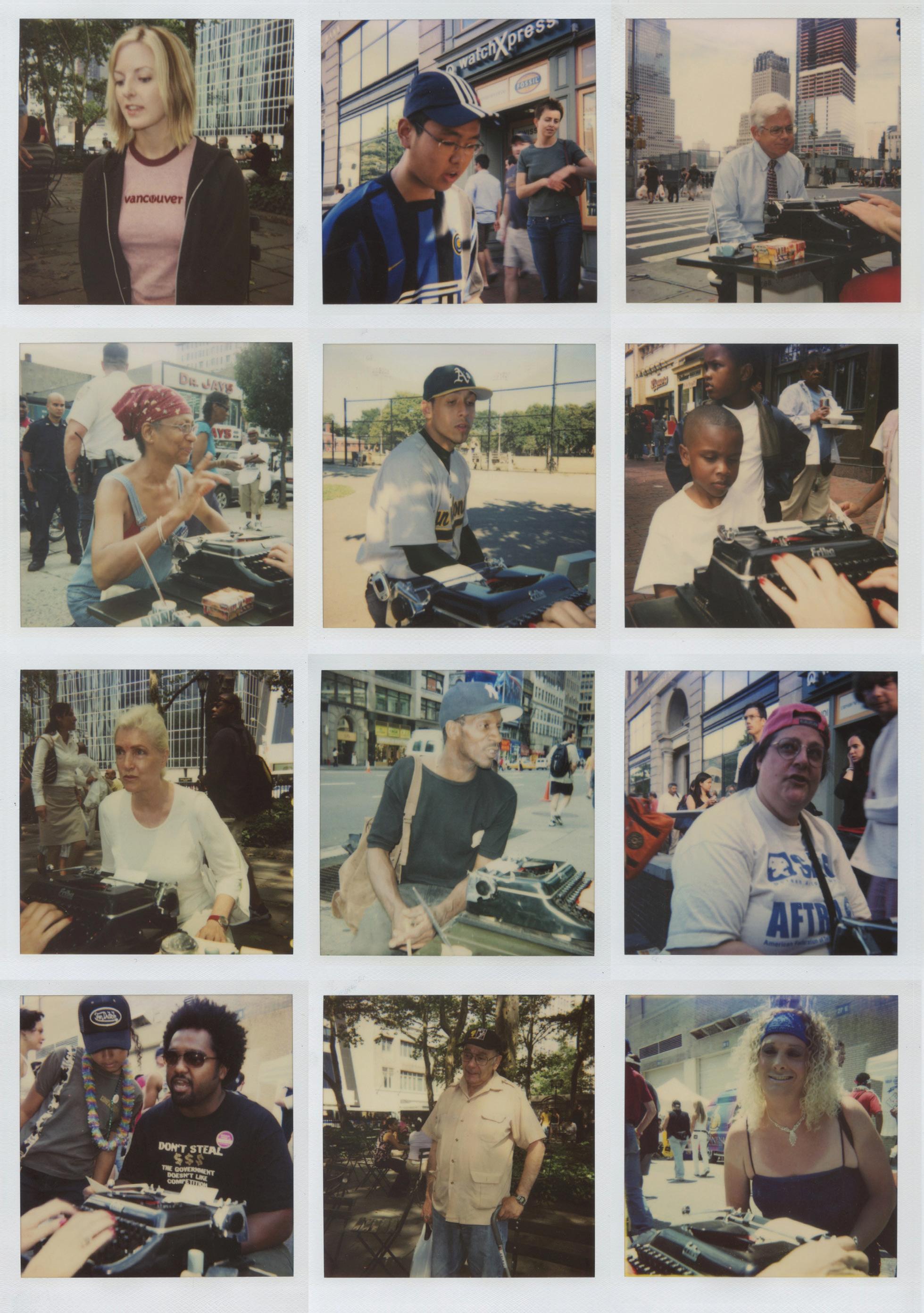

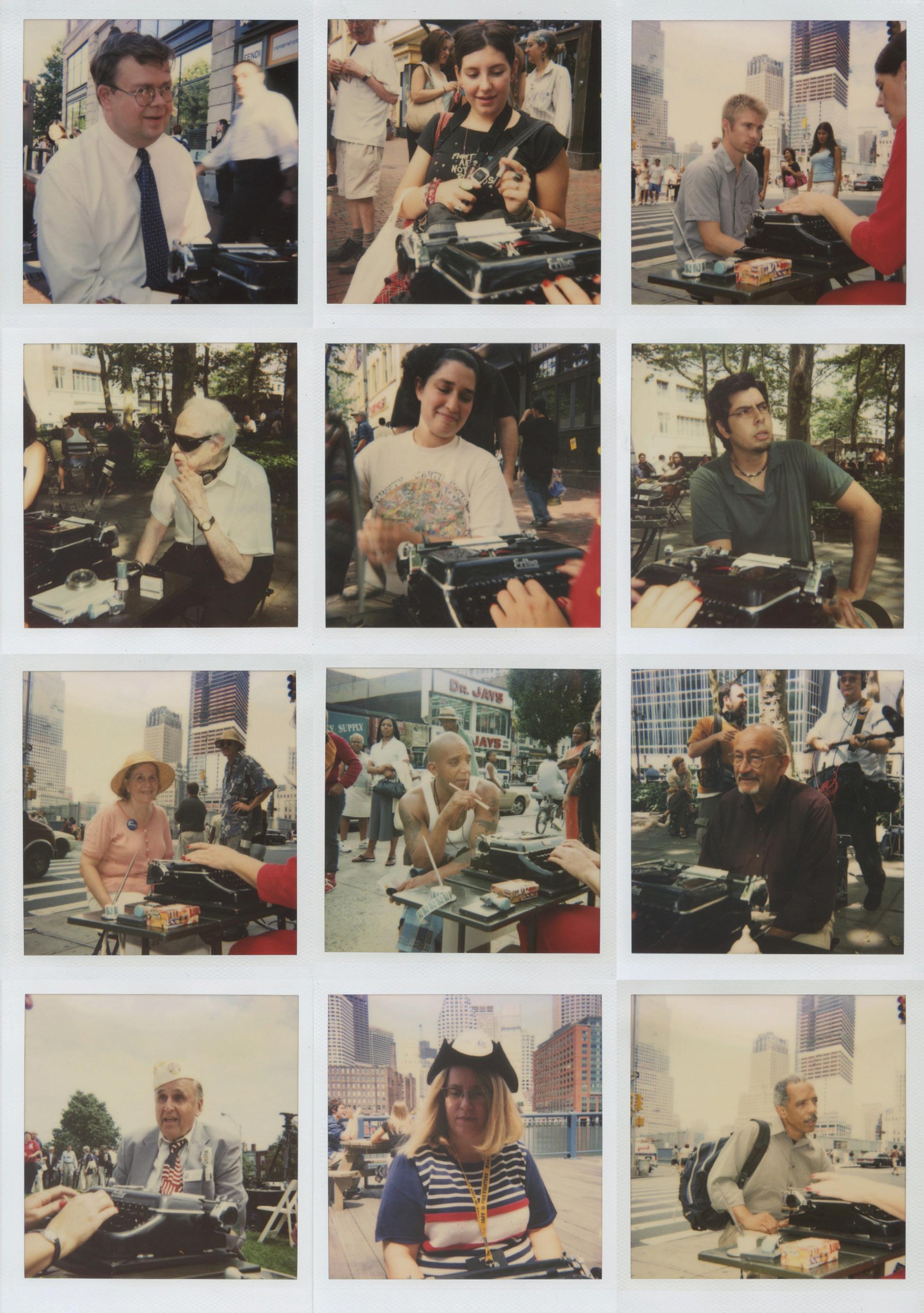

Overleaf: Portrait of Sheryl Oring by Sarah Barrick. Inside front cover: Polaroids by Damaso Reyes, 2004.

Corey Dzenko, Ph.D.

Small acts have big mythologies. Despite their scale, they are accompanied by enduring beliefs in their capacity to have sustained and meaningful impact. The accumulation of small acts, across time and space, repeated and determined, can multiply and grow enough to topple the largest bastion.

- Radhika Subramaniam

“If I were the president, what would you wish to say to me?” To ask a question is a small act. To listen could be a small act, too. Yet, in our era of hyper-partisanship and echo chambers, these small civic acts resonate profoundly. It is in this context that we bring Sheryl Oring’s I Wish to Say to the DiMattio Gallery.

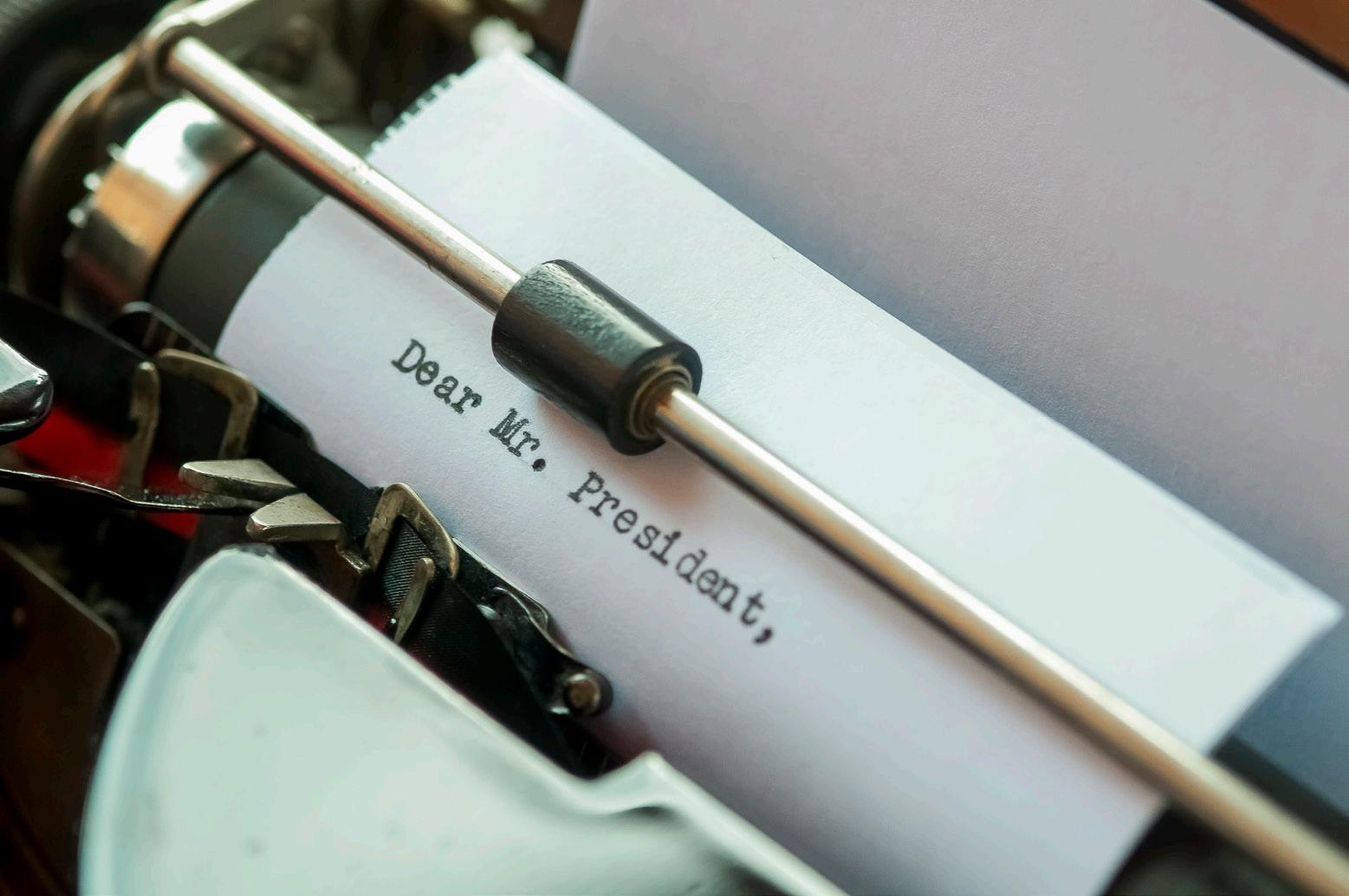

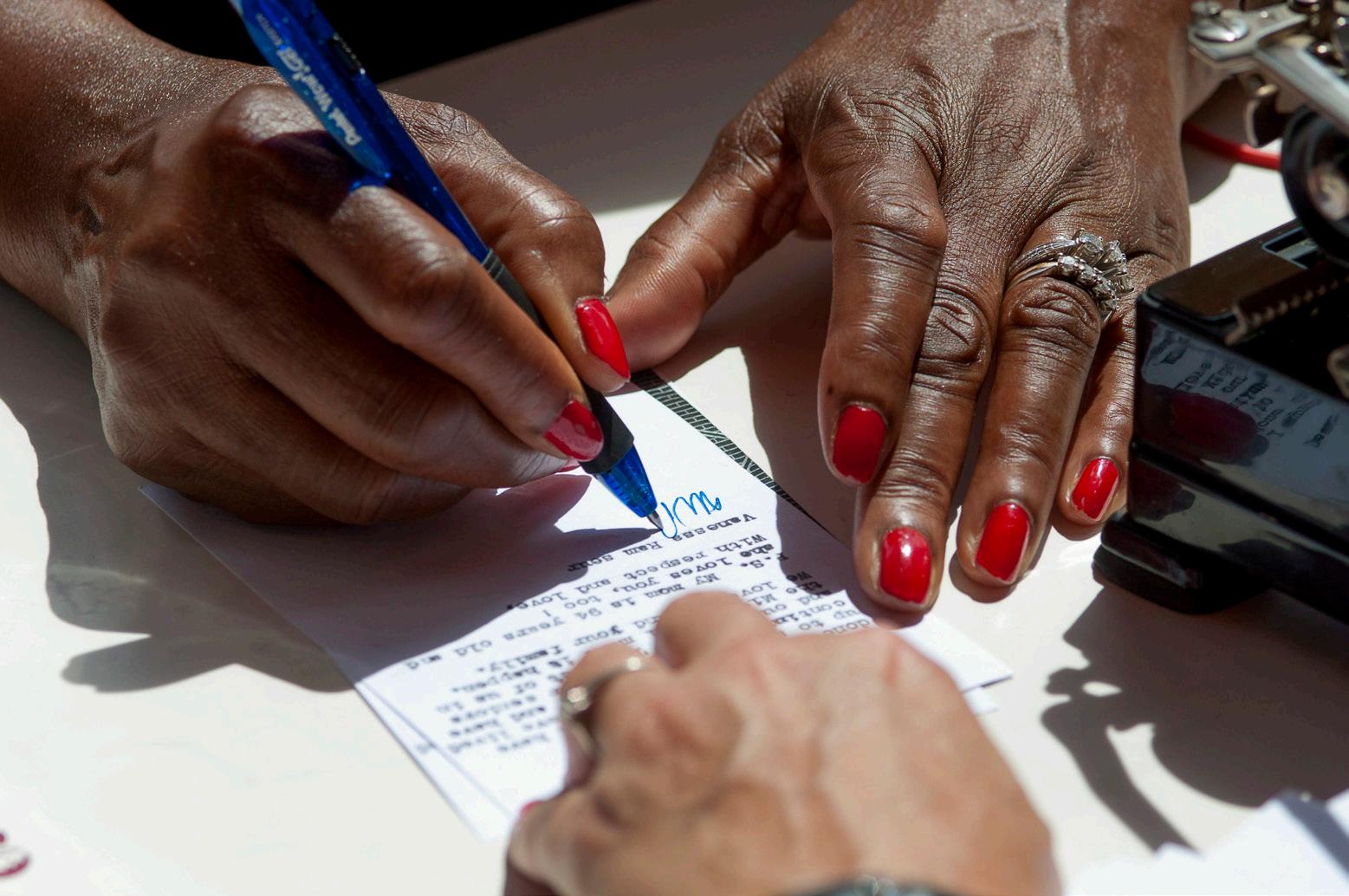

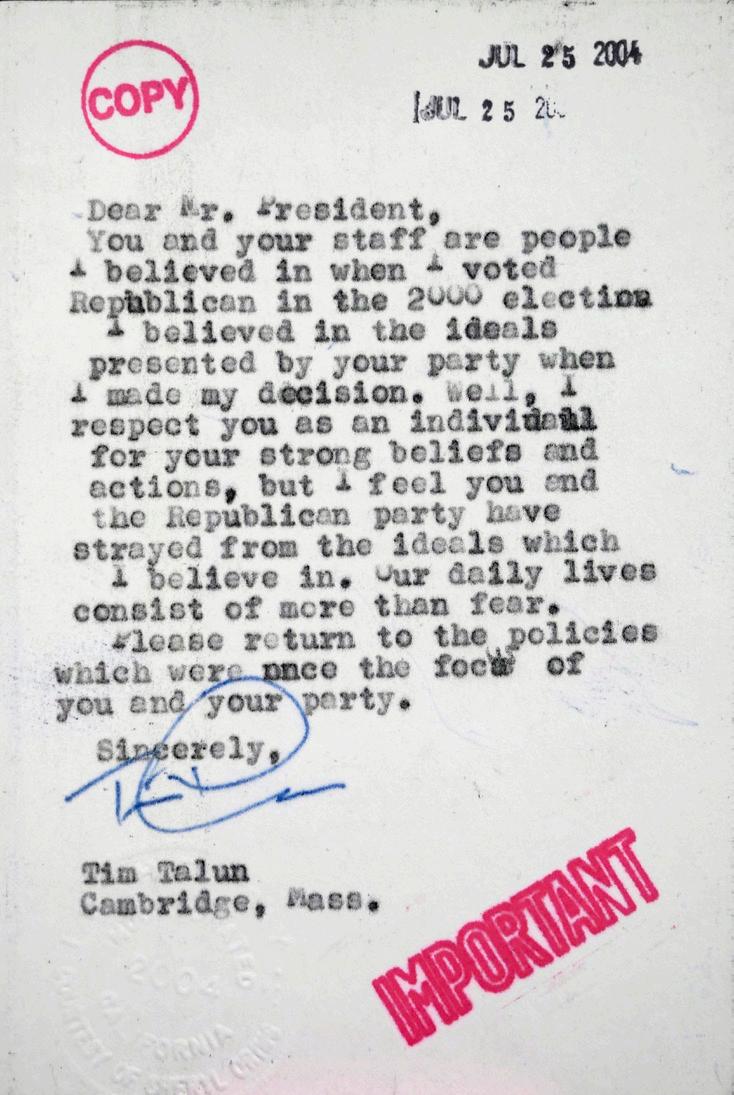

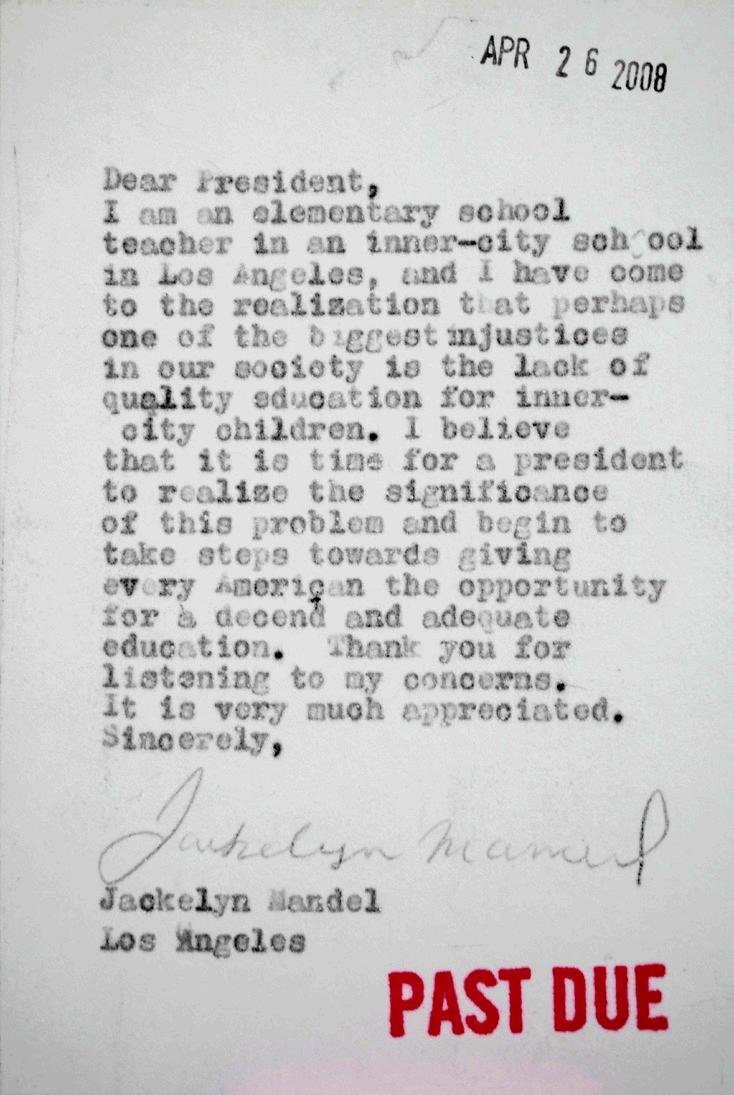

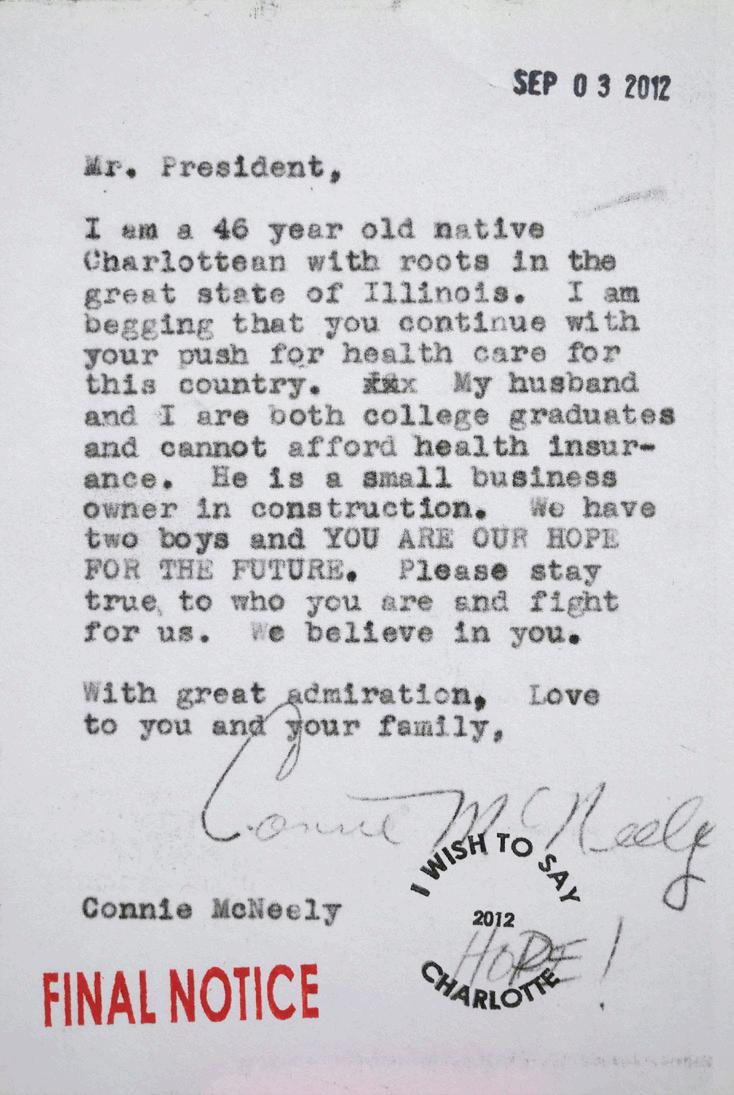

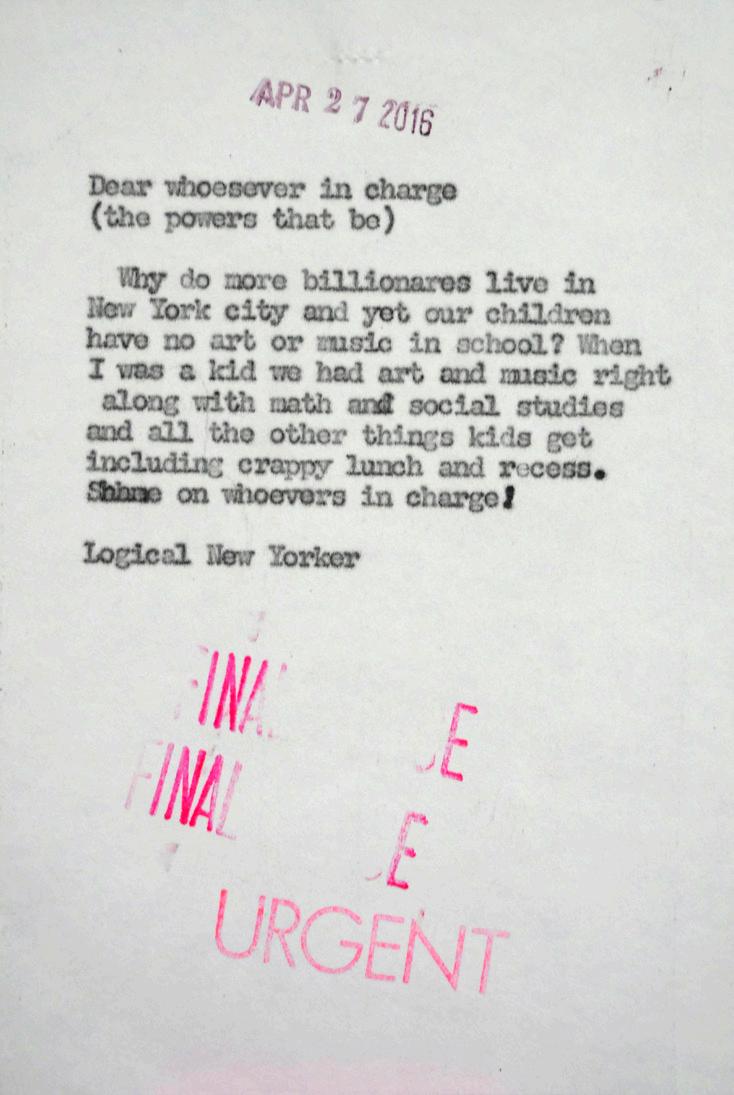

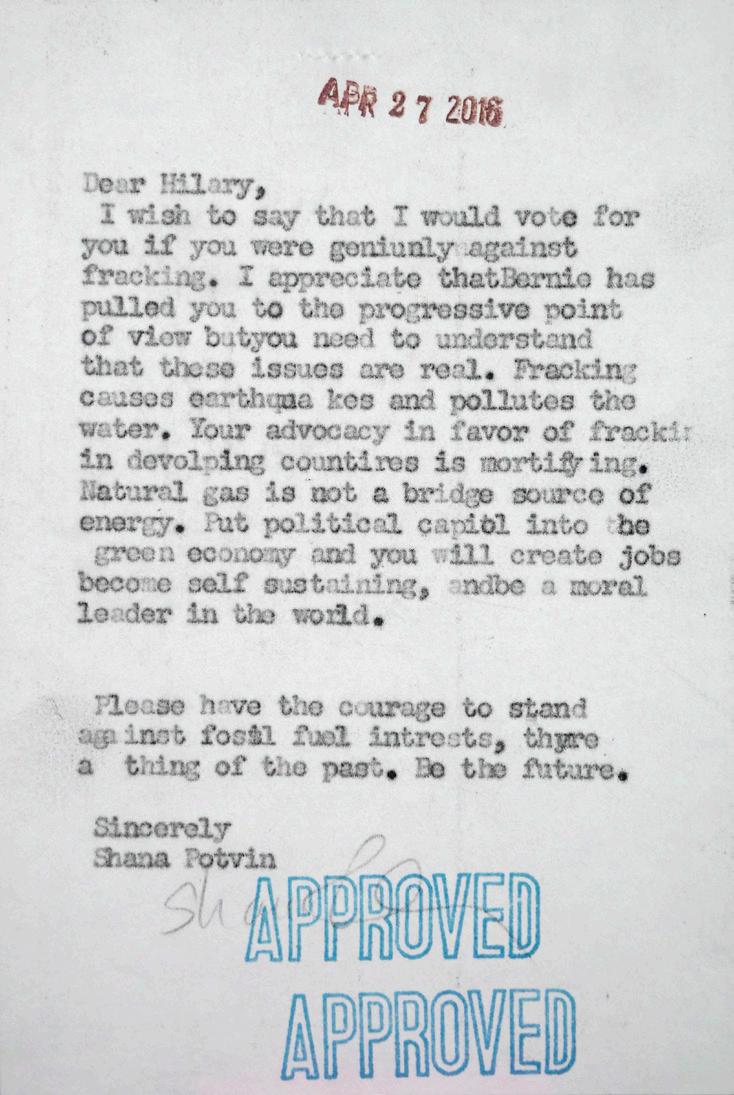

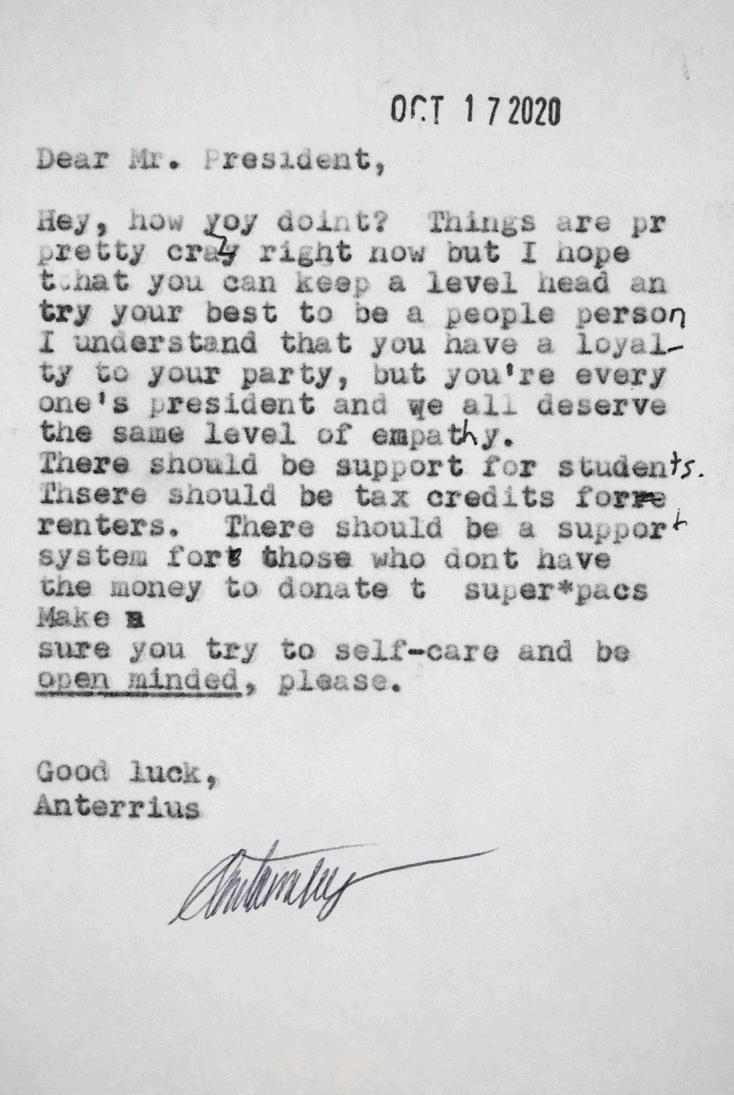

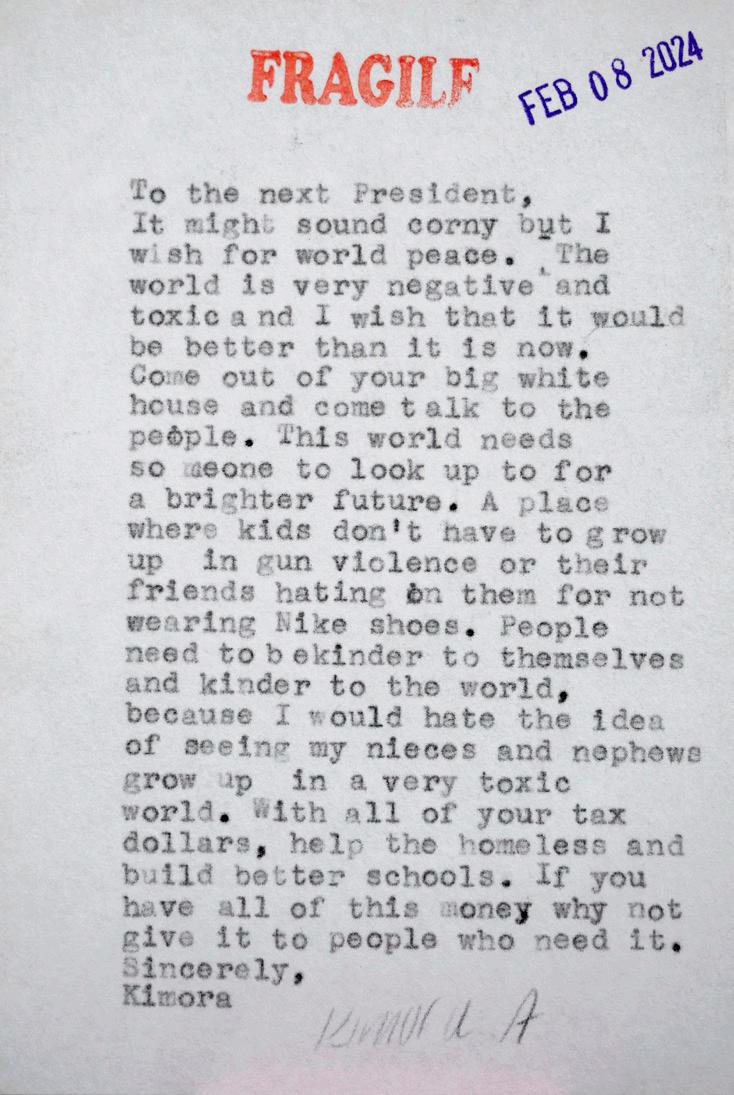

Now enacted across the time and space of twenty years, Oring asks the public to dictate postcards to the current or next US president. She types the messages verbatim with a typewriter, only limited by the size of a standard index card. Carbon paper makes a duplicate of each message—one for her to exhibit and archive and the second to mail to the president. To date she has typed over 4,241 postcards. This exhibition celebrates the meaningful impact of Oring’s project across the past two

decades and six US presidential election cycles. It also invites participants to write postcards now—to have a say.

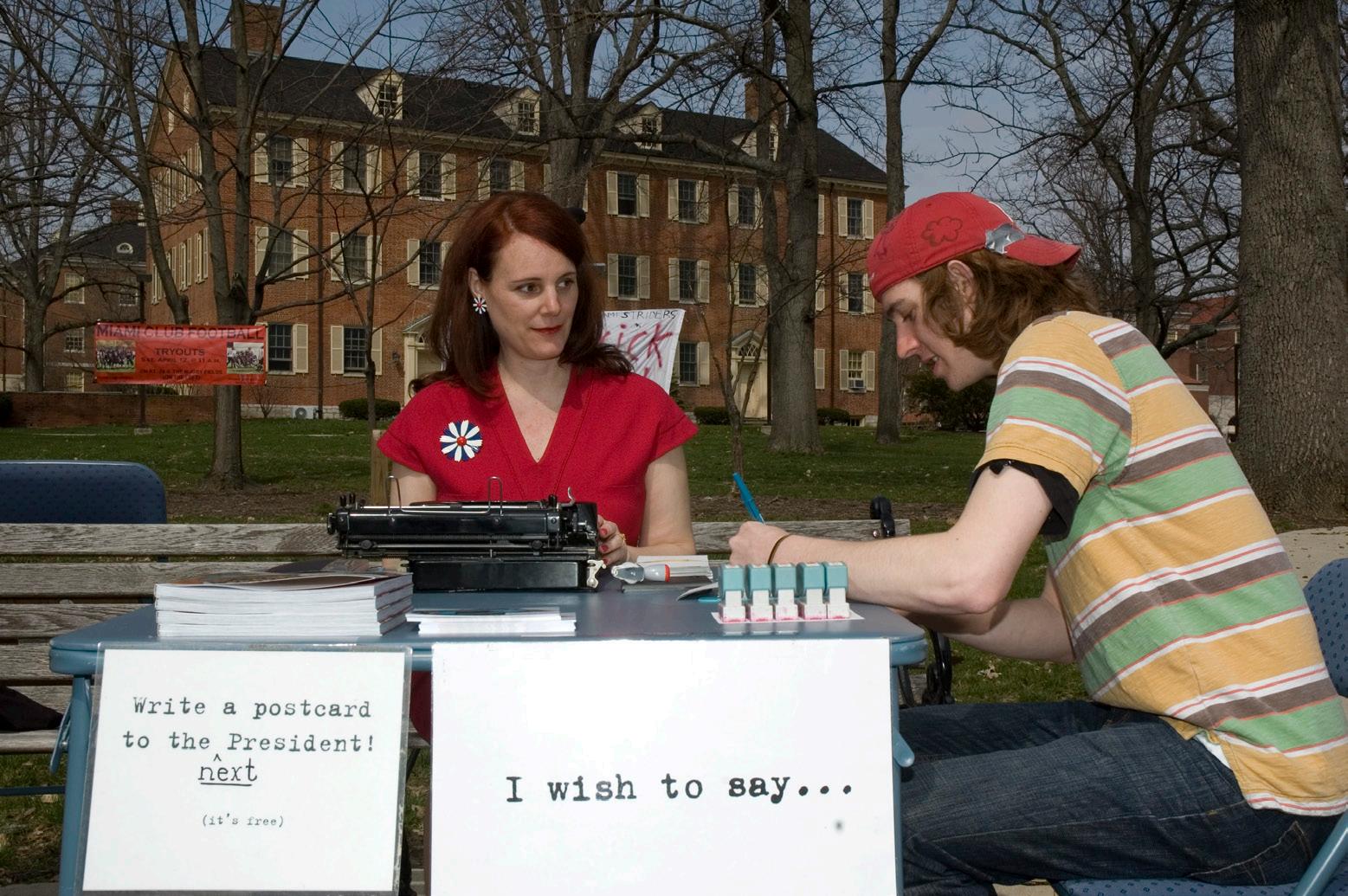

In 2004 Oring created I Wish to Say from her concern that many people’s voices were not being heard. With her experiences interviewing people from her time as a journalist, and with an invitation from the First Amendment Project, she donned a red, white, and blue outfit of a 1960s-styled secretary as she began to listen and record what people wanted to say, traveling the country with her typewriter and shoestring budget. Eventually she received additional notice with awards from Creative Capital, Franklin Furnace, and others. So, she kept traveling, listening, and typing throughout the 2008 election. In 2012 she staged I Wish to Say for the first time with a bank of multiple typists. This was the first of many times that I typed with Oring. This is where I first experienced the way the small acts of listening and typing become mighty and powerful.

Oring has made other variations to I Wish to Say across the project’s extended duration. For example, in April of 2016 she brought dozens of students from the University of North Carolina Greensboro, where she was a faculty member, to perform in New York City. Fifty of her typists sat stationed around Bryant Park to take dictation in Oring’s largest singleday event. Performers also read the public’s postcards out loud throughout the day. In October of 2016 Oring visited Monmouth University and set up her office on the patio of the student center. The university’s community dictated postcards. Students turned

these into picket signs and marched with them in the Art in Odd Places Festival in New York City. What begins as the small act of asking a question continues to reverberate in various ways. Messaging does not stop once dictation ends.

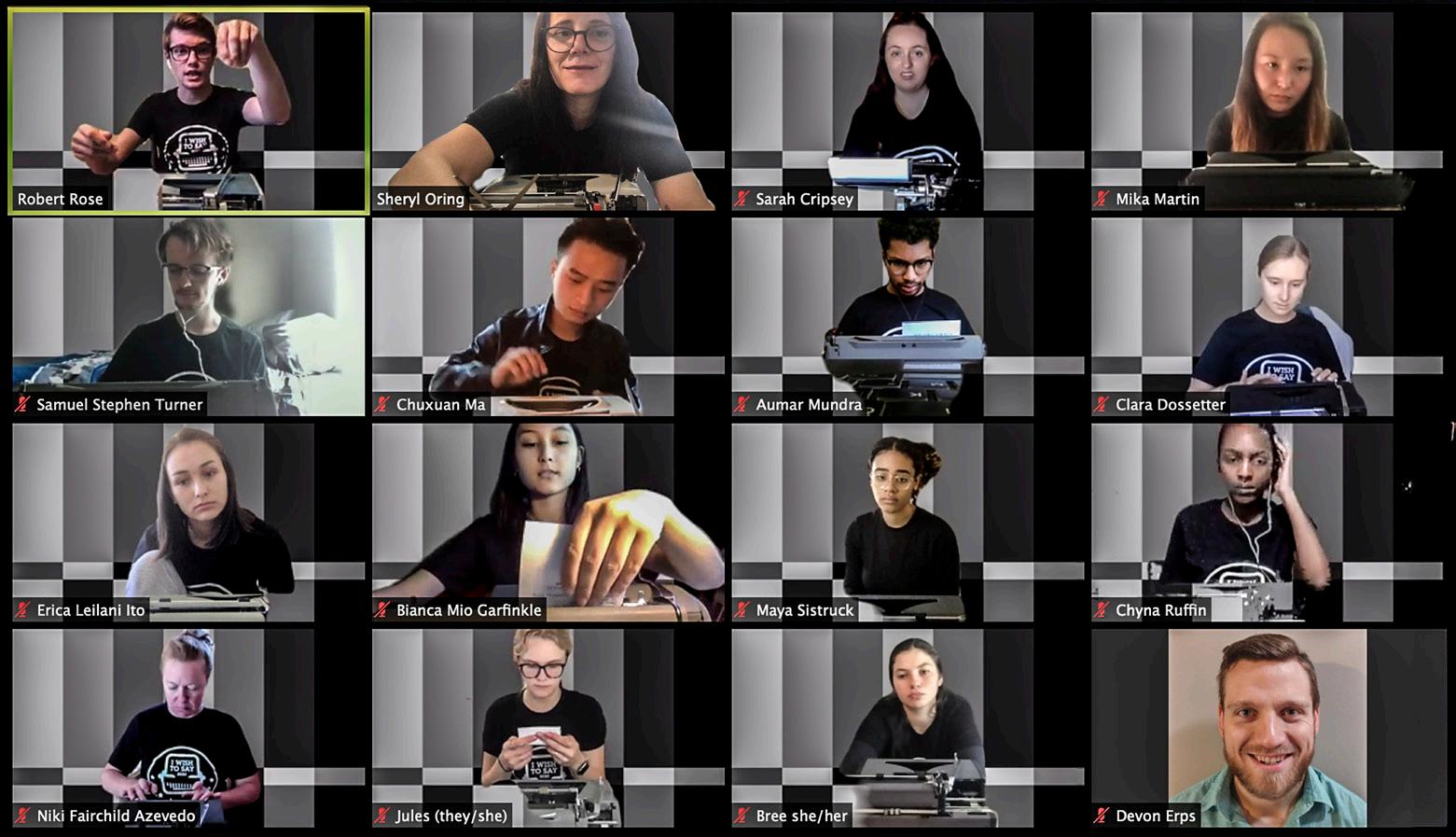

In March of 2020 Oring collected postcards from students at the University of North Carolina Charlotte. Billboards around the city announced what the students had to say just as the COVID-19 pandemic spread. The pandemic forced her to move her project into virtual and then socially distanced spaces, such as for her performance outside of the Brooklyn Public Library in October of 2020.

The first half of 2024 brought more changes. As dean of the School of Art at the University of Arts in Philadelphia, before the school’s sudden and shocking closure, Oring collaborated with high schoolers at the nearby Revolution School. As a teacher and a mother, more and more she wants to involve younger participants, encouraging their participation in democratic processes. Thus, she has begun to work with high school educators to develop curriculum connected with I Wish to Say. High school students from Neptune, Long Branch, and other neighboring towns will participate in MU’s exhibition, recording their messages to the next president.

Upon the shuttering of UArts in June 2024, the school’s community took to the streets to protest the administration’s lack of transparency around the school’s abrupt closure. UArts students protested with chants, visual images, and dance. As part of the protests, Oring went into her archive of messages, where she knew she would find a fitting remark. She grabbed a large print she had made from a postcard and took it to the streets. “We need

revival,” it proclaimed. Someone’s message from the past resounds with new meaning in the present.

Oring’s commitment to activism and making meaningful social impacts weaves throughout her art and her professional positions, first as a journalist, then as a faculty member, chair, and dean. In these roles of increasing scale or power, she remains committed to fostering diversity, equity, and inclusion with her calls for change from within various institutions. Such aims led her to initially create and then to continue I Wish to Say. Now, after twenty years of encouraging others to raise their voices, Oring is considering what she wants to say and what artforms she will use to say it. This 20th anniversary exhibition, thus, serves as a bookend, of sorts, to the first time Oring typed in public in 2004.

But to return to the small, to return to the initial interaction between the typist and the participant, I Wish to Say listens quietly, echoing only the voice of the participant and typewriter’s clacks and dings. So, what is it that you wish to say?

Corey Dzenko, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor of Art History in the Department of Art and Design at Monmouth University.

After working with the written word as a journalist, Sheryl Oring premiered her first public visual arts project Writer’s Block on May 10, 1999. This piece includes dozens of threefoot rebar cubes filled with hundreds of typewriters from the 1920s and 1930s. In its initial presentation, performers interacted with the cubes in a live dance-theater piece on Bebelplatz, a public square that was the site of an infamous 1933 Nazi book burning in Berlin. Oring was influenced by city—both its history and its present. Construction filled Berlin following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. Materials, like rebar, appeared everywhere Oring looked. As sculptural forms, Oring’s metal cubes “cage” the typewriter, censoring and taking the writer’s tools away in a symbolic statement about free expression.

Oring then developed I Wish to Say in 2004 based on an invitation from the First Amendment Project in Oakland, CA. She had displayed Writer’s Block in NYC’s Bryant Park and received an invitation to show the work on the West Coast, but the organization did not have a budget to ship her sculptures cross country. For her new social practice project, she drew on her experiences conducting person-on-the-street interviews as a journalist; her grandmother’s work as a secretary who always dressed to the nines; returning from Berlin, where she lived for six years, and feeling out of touch with what the US public thought about politics; and the Brazilian movie Central Station (1998), in which a woman takes dictation in the central train station for people who are illiterate. Whereas Writer’s Block took away the writer’s tools, I Wish to Say aimed to activate democracy by encouraging members of the public use their voices. At the start of this project, the public dictated messages to Oring dressed as 1960s styled secretary with a typewriter. She used carbon paper to make a copy, sending one to the White House and keeping one for her archive and exhibitions. Since then, she has expanded her typing pool to include additional typists and has created related artworks, expanding the initial form of her project. In this interview, exhibition curator, Corey Dzenko, and Oring discuss some of the origins of I Wish to Say, the way some of Oring’s lived experiences and activism intertwine with her artmaking, and what she may start to work on next.

Corey Dzenko: Much of your work involves the use of a typewriter and a question. Such questions can be correlated to the questions that a journalist might ask. The titles you use are also very important to you. They function like headlines that help all parts of a piece fall into place. How did you come to the title of I Wish to Say and of this exhibition, I Wish That I Had Spoken Only of It All?

Sheryl Oring: When I installed Writer’s Block at Bryant Park, we placed it on the plaza right behind the New York Public Library as a long line of the sculptures. At the head of where they were, a sculpture of Gertrude Stein sat looking out over my sculptures. I was looking at a lot of Jewish writers who were affected by the Holocaust and World War II in some way and started looking at her writing in that context.

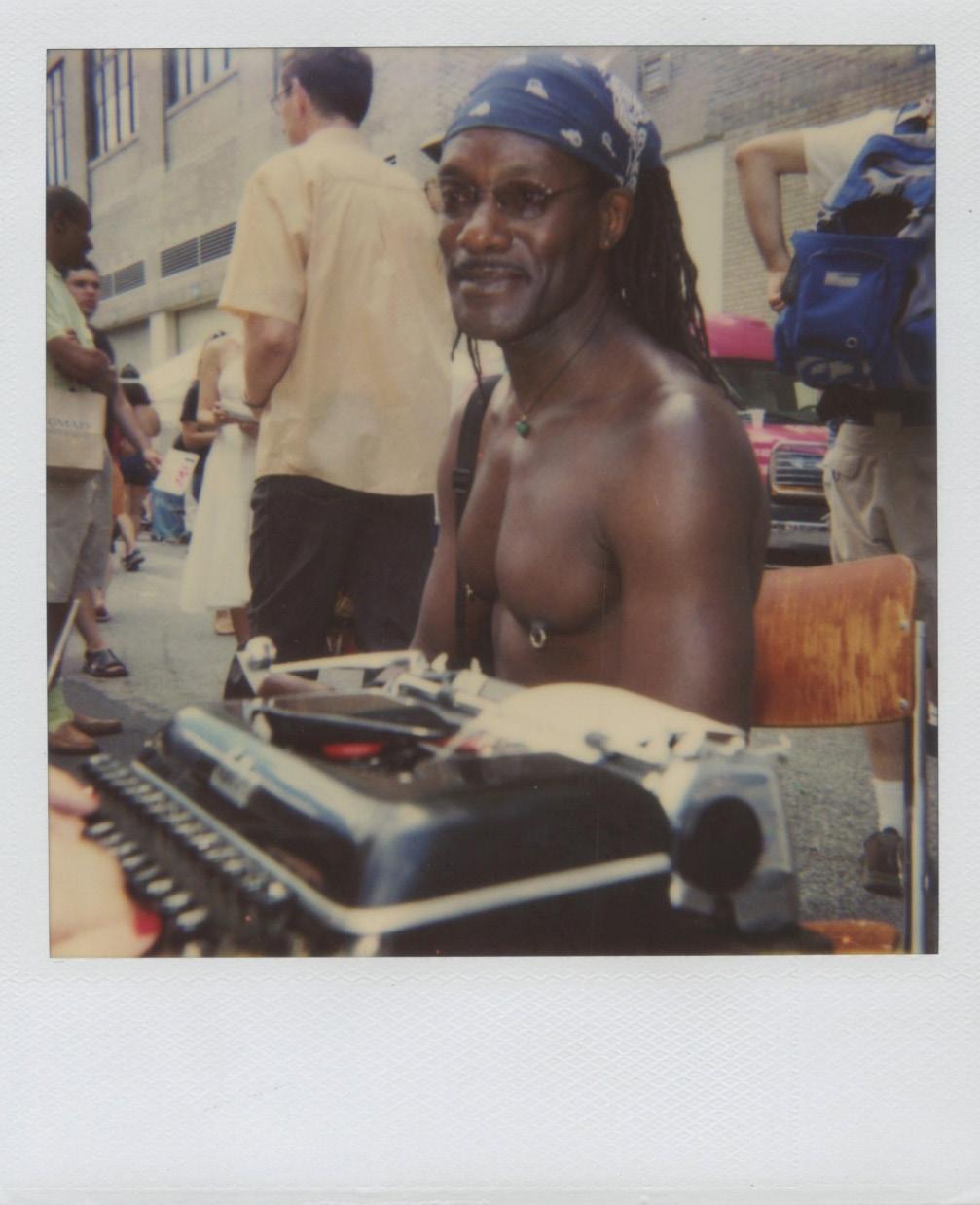

Polaroids by Damaso Reyes, 2004.

I had never been a fan of Stein. I always found her writing a little inaccessible. But because I was frequently in Bryant Park with her sculpture, I looked at her writing again. At that time, I came across Stein’s book of poetry Stanzas in Meditation. One line jumped out at me, a small excerpt from a longer text: “Which I wish to say is this / There is no beginning to an end / But there is a beginning and an end / To beginning.”

When we were looking for a title for this exhibition, I went back to Stein’s writings. I thought the short stanza that is now the exhibition’s title was appropriate as it described situations when I have not been able to speak up, or I was not heard, or there was something going on that prevented me from speaking out. That sums up this work, for both Writer’s Block and I Wish to Say

CD: Can you talk about your desire to help people say what they want to say and times you have witnessed someone’s voice silenced?

SO: I discovered Journalism when I was in college at University of Colorado in Boulder. I was searching for a major that would let me learn about a lot of different things. Two things drew me to Journalism: one was the breadth of subject matter that you could explore through the field. The other was the activist side—the way that you could advocate for the underdog and try to motivate people to facilitate change through the work that you do as an investigative journalist or by being on the side of the everyday person. I worked my way up to being on the City Desk at the San Francisco Chronicle and was in meetings where people decided what was going on the front page. Even in San Francisco during the mid-

1990s, it seemed like it was always white men on the front page. I was critical of that in meetings and kept thinking: where are the women and people of color on the front page of the newspaper?

CD: As the adage goes, the personal is political. Are there personal experiences around your voice and having a say that drove you to your project as well?

SO: There are many. For instance, I began graduate school in 2008 at University of California San Diego, after I had already started and been recognized for I Wish to Say I had a difficult time in grad school. I was an older student. I had a newborn. I already had something of an art career. I was not a typical student. There were a lot of people who, for whatever reason, were either threatened by or nasty about that. I was kicked out of a meeting because I had my child with me. It is hard to believe because it was not that long ago, but the fact that people could be so nasty about having a child made me want to hide her. I went back into this mode that I think many people my age hold onto, which is to keep everything separate. You do not want your child to be part of your work. Younger people are not like this at all. And my daughter is such a positive influence on everything I do. She now teaches me about teenagers. I am a better dean because I know what teenagers are thinking and in universities, we are trying to talk to teenagers as they start their studies.

My graduate school was the tear you down version of grad school, which I do not believe in, but I was not strong enough at that point to express myself. In fact, my

Polaroids by Damaso Reyes, 2004.

MFA thesis was something really different and involved taking evidence-like pictures of children’s clothes, nothing related to I Wish to Say. Some of the faculty told me that I could not call pictures of kids' clothing “Art.” Many people told me I could not come out of grad school still doing I Wish to Say. Thankfully, I did not listen to them. And, thankfully, I had some amazing mentors there who supported me continuing this project. Ricardo Dominguez, Louis Hock, Haim Steinbach, Teddy Cruz, and Sheldon Brown were among them.

Teddy is an architect and was one of the reasons I wanted to study it at UCSD. He asked me to consider the question of scale. I do think that the ways I have scaled up I Wish to Say and made this public, very visual impact relates to some of the things that I thought about in conversation with Teddy. Teddy was also a big advocate of change by infiltrating institutions, such as, for instance, when an architect joins the city council.

I see my work in academia as related to that mission, which I honed as a journalist, as one who reports from outside. The work that I do now is from the inside. I have changed my point of view, but I am still doing the same work that I wanted to do as a journalist many years ago and am doing it by taking on roles that have increasing power within institutions, whether as faculty, then chair, and dean. Now I have joined the board of the National Coalition Against Censorship. As you find ways to reach more people, you can make more significant change.

CD: You have described Writer’s Block as being about taking away the voice, taking away the writer’s tool and censorship. With I Wish to Say, you created a framework so other people could say what they wanted to say. But after 20 years of I Wish to Say, you no longer feel the need to be the typist. Your project can continue in various ways without you having to perform the role of secretary. What are you thinking about in terms of what you will make or say next?

SO: In addition to being about historical events, Writer’s Block is pretty clearly a selfportrait. It goes back to childhood when I felt like I was not listened to. This has continued in different realms of my life over the years. What is on my mind right now is continued criticism of certain positions of power and how to do right within those constructs. I do not know where that is going to lead creatively. We have just had a massive crisis at my institution when University of the Arts in Philadelphia closed suddenly and the school’s president stepped down. It makes me think about the people who hold positions of power without integrity. With the presidential race that is coming up, I have a lot on my mind about power and corruption. So maybe things will go in that direction.

There was a student protest that I joined about UArts’ closure. I looked through my I Wish to Say prints to make a sign – I knew there would be a perfect one. The one that jumped out was: “We need revival.” Revival. It was remarkable the way the artwork tied into real life and what was happening. There is more of that within the archive to discover as time allows.

Connecting

Johanna E. Foster, Ph.D.

As a sociologist with an art practice in portraiture, I love what Sheryl Oring has been doing over the past two decades to collectively center the voices of everyday people in the radical act of what critical sociologist C.W. Mills might have called connecting “personal troubles and public issues.” In his now classic The Sociological Imagination (1959), Mills famously asserted that the ability to link personal troubles to public issues was a necessity for an accurate understanding of one’s own individual life circumstances and life chances, and also an accurate analysis of broader social patterns. In doing this, Mills rearticulated the core tenet that we are all inevitably bound by the “dualism of human nature” (Durkheim, 1914) in that our individual experiences and unique perspectives are inescapably made possible only by the existence of social systems bigger than ourselves.

But Mills had another point to make when insisting on the importance of possessing a “sociological imagination.” Precisely because so much of what we “may wish to say” on a personal level is often deeply rooted in social systems, the act of unpacking how our seemingly purely individual concerns are collectively shared creates a path to empower individuals to change those structural and cultural arrangements that constrain and

enable us. Humanist sociologist Allan Johnson reinvigorated these axiomatic sociological principles in his The Forest and the Trees: Sociology as Life, Practice, and Promise (1997), adding that, in this dualism between the “trees” of individual experiences and the “forest” of social systems, individuals may not be able to escape the fact that “we are always participating in something larger than ourselves,” but we do always have some choice in how we will participate in those systems.

Over the past twenty years, as I Wish That I Had Spoken Only of It All makes so evident, Oring’s commitment to social practice art as a kind of participatory democracy has created vital spaces for everyday people to speak their personal troubles and to begin to speak them as public issues. This work of setting the stage for speech and for intentional listening is needed now just as much as it was in the dawn of the 21st century when Oring first began. Over the course of those two decades, as profound technological advances have made for seismic shifts in individuals’ access to information, and to avenues to voice their perspectives on all manner of topics, I know as a sociologist that, paradoxically, people feel less and less like their voices are being heard on the matters that mean most to them. People feel more and more dispossessed—rattled with profound loneliness and despair.

Not only do everyday people feel less connected, less heard, less powerful, in terms of access to society’s valuable social resources, everyday people are, in fact, losing ground in ways too numerous and too consequential to do justice in this essay, but point us to unfathomably widening wealth gaps; the exploding power of corporations and global elites; privatization and deregulation gone off the rails; a shameless gutting of social safety nets; stunning roll backs in women’s rights; the unabashed murders of black and brown people, and by agents of the state; a doubling down on the apparatuses of mass incarceration and surveillance; the seemingly endless and genocidal wars; a global pandemic that exposed the innards of a predatory class and the profiteering orchestrated through the practices of disaster capitalism; the outright seizing of the commons not only in public health, but public education and public elections, all of which speak to an organized attack on the very institutions of democracy that so many of us have taken for granted as impenetrable. Embedded in these attacks is a repression of speech along with an almost unimaginable level of distortion of reality and a swapping of truth that is so endemic to the normalization of fascism that it would be utterly comical if it were not for its so utterly sinister effects. So, we must utter back. And, indeed, it has been these very dynamics of the sinister that, twenty years ago, called Oring to expand her commitments as a journalist into the space of socially engaged visual art in the first place. Since then, Oring’s art practice has, in many ways, combined the passions of ethical journalism, and also an engaged sociological imagination, to create the radical space for thousands of people to utter back, and to be heard.

My own sociological imagination calls me to defend the personal and the uniquely human that is being demolished by the ascendance of a virulent free-market fundamentalism, and to support communities of solidarity that inspire us to keep at it in our collective

by Dhanraj Emanuel.

struggles in the public square. This is also what draws me to paint people, and it is what makes me feel so at home as I consider Oring’s work. At once, her practice opens us up to the experiences, the emotion, and the sense of belonging that can come in the act of listening and participating, calling on us to reaffirm our shared humanity in an extended era of deadly individualism and hyper rationalization. At the same time, as she centers the voices of specific people, she makes that engagement itself the point of reference, communicating the values and aspirations of a participatory democracy at a different level. In this way, I also recognize Oring as an artist who can feel at home in the community of activist sociologists in her devotion to the relational work of re/building the social ties of solidarity so crucial to defending humanist and democratic societies.

Ultimately, Oring’s work not only challenges the reification of disciplinary boundaries, but more importantly, her practice gives us hope, and with hope, prods us to take action. In a period when art, science, and the cultural institutions that exist to sustain the search for truth and meaning, and the right to question, are at the center of the bull’s eye for dangerous fundamentalisms of all kinds, it is artists like Oring who help us collectively participate in a kind of engaged citizenship that is both so vital and so precarious right now. It is in these spaces that, together, we gain the courage to utter and listen deeply, to connect and transform our personal troubles into public issues, and to resist—only all of it.

Works Cited

Durkheim, Emile. “The Dualism of Human Nature and its Social Conditions.” Durkheimian Studies 11 (1914/2005): 35-45.

Johnson, Allan. The Forest and the Trees: Sociology as Life, Practice, and Promise. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1997.

Mills, C. Wright. The Sociological Imagination. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1959.

Johanna E. Foster, Ph.D., is the Helen Bennett McMurray Endowed Chair of Social Ethics and a Professor of Sociology in the Department of Political Science and Sociology at Monmouth University. She also studies as an MFA student in Painting and Drawing at New Jersey City University.

Jason C. Fitzgerald, Ph.D.

The advent of social media platforms held the promise of an age of voice. Like the printing press, the technology of social media lowers the barriers previously erected to marginalized voices. Social media enables personal expression, which can theoretically help our communities better understand and meet the values professed by democracies. By distributing underrepresented voices to wider audiences, social media technology has the potential to strengthen democracy.

Such hope in this technology was grounded in humanism, not in the data-ism that has become our reality.1 Social media had the potential to elevate human voice by confidently centering human beings as the prime mover of communication and innovation – the way that vibrant democracies do. In reality, data-ism (not humanism) has driven social media broadcasting; market-driven algorithms exploit user information by carefully augmenting voices that induce strong emotional reactions, even at the expense of any

1 Yuval Noah Harari (2017) writes about the rise and extent of data-ism in public discourse, policy, and management. Social media platforms use data to target audience attention and drive individual behavior with near-surgical precision, leading Harari to argue that data-ism is replacing humanism as a leading paradigm for individual and social action.

true representation of what most people really think. Rather than centering humanity in the distributive power of their platforms, social media companies have centered marketuseful, user-collected data. The power of human beings’ voices is lost to the marketpower of the algorithm, a process that dehumanizes individuals in favor of data and at the expense of community.

Sheryl Oring's I Wish to Say adds humanity to the familiar “tweet-sized” messages on which so many hung their hope for a strengthened democratic voice. From the use of analogue typewriters, to the human-to-human verbal communication needed to develop the messages, to non-algorithmic exhibition displays, Oring’s extended social practice project humanizes participant voices to create a mosaic of ideas about and for our democracy. The process underlying I Wish to Say has important meanings for how we foster democratic voice within our communities and within our educational settings. During this process, three critical events converge: (1) a human being develops a message, (2) they convey that message to another human being in real-time, and (3) viewers consider that message within the constellation of messages from others.

Life-mediated Message. Participants developed the messages displayed in Oring’s exhibit in the context of life rather than in the context of a platform. Today’s digital platforms produce consumer information environments, which shape the ways that we think and react. Social media algorithms track our attention and provide more attention-grabbing items, creating an environment that interacts with and guides our reactions. These algorithms create what Alison Cohen and I termed epistemically isolated environments; we interact with and are influenced by people who think like us.2 This isolation creates a digitally mediated thought-vacuum that reinforces and amplifies (seemingly) common thoughts, limiting a diversity of ideas and opinions.

Oring’s project is different; it is life-mediated, making participants’ messages more contextualized within their lived experiences as human beings than as consumers of “feeds.” Life-mediated messages represent a diversity of experiences, rather than the thought-vacuums developed by algorithms. In an age of curated digital reaction, I Wish to Say offers a refreshing realness that is critical to genuine democratic interaction. This realness mirrors the types of communication found in youth participatory action curriculum that educators have begun embedding in their teaching. In these curricula, youth voices are shared equally without algorithmic augmentation of “strong” minority voices. To the extent that democracy can only function from the real, un-curated experiences of human beings, I Wish to Say offers a space for democracy-sustaining messages and a chance for youth to practice such genuine communication.

2 Epistemic isolation is a term related to Miranda Fricker’s (2007) epistemic injustice. Cohen and Fitzgerald (2017) extend that term to the ways that social media algorithms create artificial knowledge and information boundaries that exclude social media users from opinions that are different from their own.

Talking to Humans. Another innovation of Oring’s undertaking is grounded in the humanto-human contact experienced in the typing of the message. Research continually demonstrates that people are more extreme in their messaging and contribute to a more polarized communication environment when they are “hidden behind the screen.” Communication through another person (the typist), enables this exhibit to create a communal, civic environment where polarization might be reduced and common ground might find a home, even through individually produced messages. Decades of relationship and friendship decline have accelerated with the advent of social media. In this context, talking to other human beings, particularly around political discourse, is a counter-cultural experience. Participation in this project is a chance for youth to practice this skill.

Distributive Voice. Whereas social media platforms create a linear user experience through the “feed” feature, this exhibit provides visitors with a distributive experience. Scholarship in idea management demonstrates that linear models of learning, such as reading one post after another, limits readers’ connections between ideas. Readers forget the posts they read early in a session and rarely review what they read, even though online platforms enable to them to do so without refreshing their screens. Even if the ideas represented on social media platforms are cogent, kind, and democratically-representative, few insights can be drawn from such linear reading.

Walking through a display of I Wish to Say provides individuals and communities a brandnew experience. Visitors can sample the messages in a variety of directions. Moving back or forth, up or down, visitors can view, review, pause, and ponder the messages they read, thinking about the connections that might be made across these ideas and with themselves. The non-algorithmic nature of the display provides visitors with maximal freedom to consider and draw insight from these messages, creating an educational experience in the collective experience of the exhibit. Insightful connections enable individuals and communities to contribute to the world as this exhibit fosters an environment for such connection.

A Makerspace of Democratic Voice. Any display of I Wish to Say, then, serves as so much more than an exhibit. The process of its creation is a makerspace of democratic insight from which we can all learn. Such an undertaking reaches beyond the gallery and into the lived experiences of the youth who helped to construct this collective voice. Often, participatory civics is conducted with youth in a teacher-directed environment, where students learn to work together to address a community issue. Such whole-class exercises are important for many reasons, but what often goes unsaid is that some student voice is muted as teachers manage competing demands of administration, community, and student voice. I Wish to Say provides youth an opportunity to express themselves with full voice, unmitigated by such competing demands.

If democracy is to survive, it must be grounded in the full voice of all who live in a space. It must be grounded in humanism, not data-ism – in life-mediated rather than algorithmmediated ideas. Oring’s I Wish to Say as enacted and presented in this exhibit creates a thoughtful environment of humanity and distributive voice – an environment we all would do well to replicate and learn from.

Works Cited

Cohen, Alison K. and Jason C. Fitzgerald. “Measuring the Relational Aspects of Civic Engagement and Action.” Journal of International Social Studies 7, no. 2 (January 2017): 4-19.

Harari, Yuval Noah. Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow. New York: HarperCollins, 2017.

Jason C. Fitzgerald, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Curriculum and Instruction at Monmouth University.

February 8, 2004

February 10, 2004

April 2, 2004

April 4, 2004

April 6, 2004

April 10, 2004

April 11, 2004

April 15, 2004

April 21, 2004

June 27, 2004

July 19-22, 2004

July 23, 2004

July 25, 2004

July 26-27, 2004

August 6, 2004

August 17, 2004

August 29, 2004

August 30, 2004

August 31, 2004

September 1, 2004

September 1, 2004

September 13, 2004

September 30, 2004

October 2, 2004

October 17, 2004

October 18, 2004

October 24, 2004

November 1, 2004

November 5, 2004

January 20, 2005

March 17, 2005

September 9 & 11, 2005

September 17 & 20, 2005

September 25, 2005

October 8-9, 2005

The Canvas Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Oakland Box Theater, Oakland, CA

University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX

Border Book Festival, Mesilla, NM

University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, TX

Laundromat at the Toh'Nanees'Dizi Shopping Center, Tuba City, AZ

Las Vegas, NV

Walnut Creek, CA

San Julian Park, Los Angeles, CA

PrideFest, NYC

Bryant Park, NYC

Greenpoint, Brooklyn, NY

Central Square, Cambridge, MA

Boston, MA

Bryant Park, NYC

Foley Square, NYC

McCarren Park, Brooklyn, NY

Liberty Plaza and Harlem, NYC

Eighth Avenue, NYC

Foley Square, NYC

St. Marks Church, NYC

Junno's, NYC

Georgia State University, Woodruff Park, Atlanta, GA

NY is Book Country, NYC

Madiera Beach, FL

Tampa, FL

New Haven, CT

Delray Beach, FL

St. Petersburg, FL

McPherson Square, Washington, DC

Rotunda Gallery, Brooklyn, NY

South Street Seaport, NYC

University of Memphis, Memphis, TN

CultureFest, Battery Park, NYC

South Street Seaport, NYC

April 10, 2006

City Hall Park, NYC

September 29, 2007 Brooklyn, NY

February 21-22, 2008

March 17, 2008

March 27, 2008

March 27, 2008

April 7, 2008

College Art Association, Dallas, TX

State University of New York at Fredonia, Fredonia, NY

Book Launch, NYC

Salisbury University, Salisbury, MD

Miami University, Oxford, OH

April 18, 2008 Oakland, CA

April 19, 2008

April 22, 2008

April 23, 2008

April 26, 2008

April 28, 2008

April 30, 2008

May 19-20, 2008

June 7, 2008

The Embarcadero, San Francisco, CA

St. Mary's College of California, Moraga, CA

Middlebury Institute of International Studies, Monterey, CA

Venice Beach Baordwalk, Los Angeles, CA

Pitzer College, Claremont, CA

Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ

Bryant Park, NYC

Printer's Row Bookfair, Chicago, IL

June 8, 2008 Chicago, IL

September 25, 2008

Wichita State University, Wichita, KS

October 1, 2008

October 1, 2008

October 27, 2008

November 15, 2008

Belmont University, Nashville, TN

Victoria College, Victoria, TX

Muhlenberg College, Allentown, PA

Mcormick Freedom Museum, Chicago, IL

November 21, 2008 Longwood University, Farmville, VA

December 5, 2008

May 1, 2010

June 10, 2010

September 17, 2010

June 16, 2011

University of California, San Diego, San Diego, CA

San Diego, CA

San Diego Museum of Art, San Diego, CA

01SJ Biennial, San Jose, CA

Americans for the Arts Convention, San Diego, CA

September 3, 2012 CarolinaFest, Charlotte, NC

July 25-26, 2015 Out of Sight Festival, Chicago, IL

February 4, 2016 College Art Association, Washington, DC

April 27, 2016

PEN World Voices Festival, Bryant Park, NYC

September 23, 2016 University of Colorado, Boulder, CO

September 29, 2016 Appalachian State University, Boone, NC

October 6, 2016

Monmouth University, West Long Branch, NJ

October 11, 2016 Madison Square Park, NYC

October 14-15, 2016 CT Summit, Washington, DC

October 19, 2016 Honors School, University of North Carolina Greensboro, Greensboro, NC

October 18 & 20, 2016 Greensboro Montessori School, Greensboro, NC

October 27, 2016

November 1, 2016

Weatherspoon Art Museum, Greensboro, NC

Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art (SECCA), Winston-Salem, NC

November 4, 2016 Contemporary Art Museum (CAM) Raleigh, Raleigh, NC

November 8, 2016 Elsewhere, Greensboro, NC

November 15, 2016

January 18, 2017

St. Joseph's College of Maine, Standish, ME

University of North Carolina Greensboro, Greensboro, NC

February 4, 2017 Elsewhere, Greensboro, NC

February 11, 2017 Elsewhere, Greensboro, NC

February 16, 2017 College Art Association, NYC

February 18, 2017 Elsewhere, Greensboro, NC

February 25, 2017 Elsewhere, Greensboro, NC

March 4-18, 2017

March 25, 2017

April 1, 2017

Elsewhere, Greensboro, NC

Elsewhere, Greensboro, NC

Elsewhere, Greensboro, NC

April 13, 2017 Alexandria, VA

April 15, 2017

April 20, 2017

Elsewhere, Greensboro, NC

Elsewhere, Greensboro, NC

April 28-29, 2017 Pittsburgh, PA

May 21-22, 2017

Oakland Book Festival, Oakland, CA

July 20 & 22, 2017 Reno, NV

September 8, 2017

November 11, 2017

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI

Ringling College of Art and Design, Sarasota, FL

September 19, 2018 Art Prize, Grand Rapids, MI

September 21-23, 2018 Art Prize, Grand Rapids, MI

September 27, 2018

October 12, 2018

Washington and Lee University, Lexington City, VA

Ringling College of Art and Design, Sarasota, FL

February 13, 2019 College Art Association, NYC

March 21, 2019

April 3, 2019

May 3, 2019

May 16, 2019

University of North Carolina Greensboro, Greensboro, NC

University of North Carolina Greensboro, Greensboro, NC

Elsewhere, Greensboro, NC

Greensboro Book Festival, Greensboro, NC

June 1, 2019 Raleigh, NC

February 12, 2020 College Art Association, Chicago, IL

March 11-12, 2020

University of North Carolina Charlotte, Charlotte, NC

October 17, 2020 28th Amendment Project, Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn, NY

Fall 2020

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI

Fall 2020 Wayne State University, Detroit, MI

November 2020 Neo Futurists, NYC

March 13, 2022

December 3, 2023

February 8 & 15, 2024

April 8, 2024

August 15, 2024

August 19, 2024

August 20, 2024

September 19, 2024

Washington National Cathedral, Washington, DC

Weitzman National Museum of American Jewish History, Philadelphia, PA

University of the Arts and Revolution School, Philadelphia, PA

Westtown School, West Chester, PA

South Broad and Philly Typewriter, Philadelphia, PA

Fine Arts Building with Out of Site, Chicago, IL

Co-Prosperity and Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, IL

Monmouth University, West Long Branch, NJ

Sheryl Oring joins the protests about the University of the Arts sudden closure, Philadelphia, PA. June 5, 2024.

Sheryl Oring examines critical social issues through projects that incorporate old and new media to tell stories, examine public opinion, and foster open exchange. Using tools typically employed by journalists (the camera, the typewriter, the pen, the interview, and the archive), she builds on her experience in her former profession to create installations, performances, artist books, and internet-based works that address themes of citizenship, free expression, first amendment rights, story-telling, and activism through art. Oring received her MFA from the University of California at San Diego. She is currently a board member for the National Coalition Against Censorship. She has held several academic positions, most recently serving as the Dean of the School of Art at University of the Arts in Philadelphia.

Oring has shown her work at the O1SJ Biennial; Bryant Park in Manhattan; the Brooklyn Public Library; and the Jewish Museum Berlin. She has also presented work at Art in Odd Places in New York; the Art Prospect festival in St. Petersburg, Russia; Encuentro in São Paolo, Brazil; and the International Symposium on Electronic Art in Dubai. She has completed public art commissions at the San Diego and Tampa International Airports. Collecting institutions include the Library of Congress; Museum of Modern Art; Tate Britain; Bibliothèque nationale de Luxembourg; and many others.

A project of this scope and magnitude has required an army of assistants and collaborators to create. My deepest thanks to all of the 4,241 people (and more by the time this is printed) who sat down at my desk and shared their thoughts, concerns, and personal stories with me and one of the US presidents. It was an honor to type for you.

My students have played a significant role in this work and I am always inspired by the energy they bring to it. Thank you to Sherrill Roland, Robert Rose, Jasmine Best, Wabwila Mugala, Christian Carter-Ross, and so many others who have helped along the way.

Curators who have presented the work have deepened my understanding of it and worked with me to expand its reach. Radhika Subramaniam at The New School was one of the first to support this work, along with Ed Woodham of Art in Odd Places. Huge thanks to Cora Fisher and Jakab Orsos at the Brooklyn Public Library; Srimoyee Mitra at the University of Michigan’s Stamps Gallery; of course, Corey Dzenko, who has engaged with the project in various ways since 2012.

Funders including Creative Capital, Franklin Furnace, New York Foundation for the Arts, and the North Carolina Arts Council have made this work possible. A huge thanks to all of you.

Documentation has always been an important aspect of this work, and my deepest thanks goes out to all of the photographers and videographers I have worked with over the years. Dhanraj Emanuel tirelessly documented nearly a decade of this work. For that, I am greatly thankful.

Deep gratitude goes to my dear friend Stephanie Elizondo Griest, who has supported this work since the very beginning and at every turn along the way, and to my new friends at Philly Typewriter, who keep my machines in the best of order.

And finally, heartfelt thanks to my daughter, Shira Emanuel. A few years ago, I asked her whether I should keep doing this work because every time I type, I have to leave home for a few days or even longer. Without hesitating, she looked me in the eye and said: “Never stop typing, Mama.” And so here we are, Shira, one of her best friends, myself and a car full of supplies, headed to Chicago to type on the streets during the Democratic National Convention in 2024.

This exhibition took the help of many to bring it into being. First and foremost, thank you to Sheryl Oring for the generosity of her project and for celebrating and showcasing its anniversary milestone with us at Monmouth University. To Scott Knauer for all of his assistance with the gallery and working through various ideas for this exhibition.

To Jason Fitzgerald and Johanna Foster for contributing catalog essays, helping to organize student volunteers and typists for both MU and local high schools, and for teaching as part of a series of teach-ins related to this exhibition. To the additional MU faculty who are part of the Fall 2024 teach-ins: Kristin Bluemel, Kimberly Callas, and Katherine Parkin. And to Melissa Alvaré for also helping organize MU students as typists.

To Mark Ludak and Mike Richison for the photography and design work for this show. To Michael McClellan, Gay Falk, and Dickie Cox for offering suggestions on many, many drafts of grant applications and other texts.

To the ArtNOW committee, Helen Bennett McMurray Endowed Chair of Social Ethics, Department of Art and Design, and Department of Curriculum and Instruction for helping fund this project. To Enrica Taormina, Linda Rossi, Christine Benol, Rich Veit, and those in MU’s various offices who continue to support our work with the arts.

To our educational partners at Long Branch Public Schools, Neptune Public Schools, and the League of Women Voters of New Jersey for their support of this project and commitment to civic voice and participation.

To our MU student volunteers who will type at various events throughout the exhibition’s duration. And to all of those who participate… Thank you.

This exhibition was made possible with funding from the Edna Wright Andrade Fund of the Philadelphia Foundation and from the Diversity Innovation Grant Program coordinated by the Office of the Provost and Intercultural Center at Monmouth University.

Inside back cover: Polaroids by Damaso Reyes, 2004.

www.monmouth.edu/department-of-art-and-design

www.monmouth.edu/mca