Crafting Non-Standard: Reimagining Materiality’s Intrinsic Vitality towards Digital Craftsmanship

Iqbal Utomo ucbvisu@ucl.ac.uk/ 24211828

a study of “Soil and Protoplasm: Designing the Hylozoic Ground Component System” by Philip Beesley

BARC0061 – Contextual Theory MArch Design for Manufacture

Crafting Non-Standard: Reimagining Materiality's Intrinsic Vitality towards Digital Craftsmanship

Introduction

“Each thing [res], as far as it can by its own power, strives [conatur] to persevere in its own being,” said Spinoza to ascribe peculiar characteristics of all beings. Conatur refers to the power that belongs to regardless of whether they are living or ‘unliving’ things, considering their forces given to persist within their existence, hence they are equal 1

Hylozoic Ground was an installation project created by a renowned architect, artist, and designer, Philip Beesley, with other engineers from Canada, Britain, and Denmark, exploring new approaches of architectural building Inspired by “Hylozoism”, an ancient Greek term for “all materials possess life”, it was an endeavor to see life arising from the quickening of air, water, and stones, seedling earth with the earliest form of life 2 This installation in which was questioning the ability of soil to be constructed was a suspended and planted geotextiles forming a ‘fertile’ matrix akin to thickets and groves. Embedded with responsive devices such as proximity sensors to recognize human presence, the installation was to be an inquiry to develop new layers of synthetic soil as a primary architectural building that might shape the future of architecture3 .

This paper investigates the role of “New Materialism”, a new paradigm in architectural discourse that underpins Hylozoic Ground and argues that this paradigm shift could potentially redefine the future of craftsmanship through embedding digital/ computational tools and their approaches, especially dealing with complex, customized (non-standard4) design.

Divided into two chapters, the first part discusses about digital poetics associated with Hylozoic Ground’s metaphorical approach of celebrating materials being alive and which resonates with John Ruskin’s, a renowned British figure, concern of the absence of spirituality within construction in his time which is subsequently challenged nowadays by the emergence of digital or computation era5 This part at first introduces the development of paradigms towards materials by philosophers’ thoughts contributing to the emergence of “New Materialism”. Given this shift, the chapter will delve into its practicality within making’s realm.

After acknowledging the significance of weaving with material which is emphasized by the potential of real-time interaction using digital technologies, the second part discusses how those tools could potentially allow us to highlight material’s inherent capacity, as the implication of New Materialism Despite their outstanding advantages and encountered challenges, the computation workflow could lead to successfully dealing with architectural works’ complexity, particularly for non-standard project’s framework The discussion eventually underlines the possibility of enriching the future craftsmanship by the aid of digital technologies.

1 Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter, A Political Ecology of Things (Duke University Press, 2010), https://doi.org/doi:10.1515/9780822391623, p2.

2 Philip Beesley and Rachel Armstrong, “Soil and Protoplasm: The Hylozoic Ground Project,” Architectural Design 81 (November 2011): 78–89, https://doi.org/10.1002/ad.1215, 156.

3 Beesley and Armstrong, “Soil and Protoplasm: The Hylozoic Ground Project.”, p139.

4 Fabian Scheurer, “Digital Craftsmanship: From Thinking to Modeling to Building,” in Design - Assembly - Industry, ed. Scott Marble (Birkhäuser, 2013), 110–31, https://doi.org/doi:10.1515/9783034612173.110, p115.

5 Antoine Picon, “Digital Fabrication, between Disruption and Nostalgia,” in Instabilities and Potentialities (Routledge, 2019), 223–38, p226.

Crafting Non-Standard: Reimagining Materiality's Intrinsic Vitality towards Digital Craftsmanship

Discussion

Digital Poetics

Material culture has been evolving into its contemporary breakthrough for hundreds of years Back to the inventions period, traditional view towards materials was discovered and represented by Newtonian and Aristotelian style which both shared the same interpretation, i.e. matter is inert, obedient receptacle of form superimposed by the outside or external forces (e.g. general laws)7 In more detail, Aristotle defined it as hylomorphic, standing for ‘form’ (morphe) and matter (hyle), in which form was described that which is imposed by an agent with a particular design in mind and matter which is inert, passive, and waiting to be imposed upon8 These opinions showed that matter does not have their own capability to act, make, or affect. They are supposed to wait for another active agent giving them shapes or movement.

Contrary to this prejudice towards materials, latest paradigm of ‘New Materialism’, which was subsequently coined after a philosopher, Manuel DeLanda, discovered this new conception in the material world, had shown the opposite view where materials are obviously alive9 Other influences also came with their own thoughts. For instance, in her work, Vibrant Matter, Jane Bennett explained Spinoza’s view in which materials strive to persist in existence. Furthermore, Hent De Vries’ opinion was also introduced of that which material attempts to absolve from human knowledge. However, Bennett claimed this epistemological approach as not strong enough and needed to be shifted into more ontological to be more looking at what materials can do, their ‘thing-power’10 Materials are then no longer seen as inert or passive, but inherently animated11 .

Apart from those abstract interpretations from previous concepts, Tim Ingold brought other opinions which are more practical. Paul Klee, a painter within Antoine Picon’s work, wrote ‘Form is the end, death”, yet “Form-giving is life” followed by Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, two philosophers, arguing that it is not between matter and form like Aristotelian view, yet between materials and forces12 Overall, these two views criticized the traditional hylomorphic attitude distinguishing between matter and form13 Moreover, Ingold provided a more detailed example of carpenter that between ‘surrenders to the wood’ and/or ‘follows where it leads’ and ended up with this etymologically correct term where the carpenter both means as ‘ weaver and maker’ 14 . Here, we could see that giving voice to the material to show their embedded qualities is through weaving with their properties, that is wood grain in this case. This acknowledgment leads to such understanding of a simple rule of thumb introduced by Ingold, i.e. to “follow the materials”15 . Such dilemmas existed showing the contradictory appearance of this new material understanding. Here, positivistic movement that embraces reasoning over subjectivity became

7 Achim Menges, “Fusing the Computational and the Physical: Towards a Novel Material Culture,” Architectural Design (Conde Nast Publications, Inc., September 1, 2015), https://doi.org/10.1002/ad.1947, p10.

8 Tim Ingold, “The Textility of Making,” Cambridge Journal of Economics 34, no. 1 (July 9, 2009): 91–102, https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bep042, p92.

9 Menges, “Fusing the Computational and the Physical: Towards a Novel Material Culture.”, p10.

10 Bennett, Vibrant Matter, p2-3.

11 Picon, “Digital Fabrication, between Disruption and Nostalgia.”, p223.

12 Ingold, “The Textility of Making.”, p91-92.

13 Picon, “Digital Fabrication, between Disruption and Nostalgia.”, p224.

14 Ingold, “The Textility of Making.”, p92.

15 Ingold, “The Textility of Making.”, p94.

prevalent within New Materialism discourse. For example, in global warming issues, practical solutions more than mere dialectics became more tangible, so does between digital fabrication and materiality16 Therefore, contrary to advantages evoked by computation that fosters storing and dealing with a huge amount of numerical binary information, digital era has led what Timothy Ingold and Richard Sennett perceived as “the lost authenticity of craftsmanship”, considering Ruskin’s concern of spiritual inspiration noticeable in ornaments as a result of intimate interaction between hand and mind17

Besides those looming evidence, such technologies provide practicality within this digital age. Realtime interaction with materiality eventually became tangible digital tools and fabrication, enabling us to derive material logic directly. The need to follow the materials is now able to be attained using scanning technologies18 However, this encouragement did not take place within Hylozoic Ground albeit its aforementioned reason: to see life arising from such chemical substances19 . This metaphorical execution still resembled with often-quoted modernists attempts of ‘truth to materials’ rather than a ‘truly generative exploration’ driven by material (material-driven design)20 Instead, this installation distilled natural principles through computation, simulation, and fabrication of previously engineered materials, similar to ‘biomimetics’ projects by Jan Knippers and Steffen Reicher on their experiments of installation embracing hygroscopic process and fibrous tectonics21

16 Ingold, “The Textility of Making.”, p231-232.

17 Ingold, “The Textility of Making.”, p225-226.

18 Ingold, “The Textility of Making.”, p225.

19 Beesley and Armstrong, “Soil and Protoplasm: The Hylozoic Ground Project.”, p156.

20 Menges, “Fusing the Computational and the Physical: Towards a Novel Material Culture.”, p10.

21 Menges, “Fusing the Computational and the Physical: Towards a Novel Material Culture.”, p13.

22 Beesley and Armstrong, “Soil and Protoplasm: The Hylozoic Ground Project.”

23 Menges, “Fusing the Computational and the Physical: Towards a Novel Material Culture.”, p13.

Crafting Non-Standard: Reimagining Materiality's Intrinsic Vitality towards Digital Craftsmanship

Nevertheless, discourses of New Materialism offered potentials, for instance inspiring us for de-instrumentalization of humankind since as Bennett wrote that they are ‘walking, talking minerals’ 24 Nostalgia of subjectivity also becomes a game changer to trigger further research of digital poetics, especially for non-standard projects in which installations, and other narrative entities, ‘evoke stories’ 25 .

Towards Digital Craftsmanship

Dealing with poetic materiality does have its precedent. Within contemporary timeframe, Phillippe Block, Tom Van Mele, and Matthias Rippmann showed computation’s capabilities to create such expressive and efficient masonry surface structures using digital form-finding combined with manufacturing approaches 26 . Menges stated of this project’s approach27:

Not only can materiality become an active driver in design; computation also enables an expanded understanding of materialization, which can now be conceived as a ‘generative process’ in design rather than just its ‘physical execution’

This quotation, and their Armadillo Vaults project28 , challenges poetic entities which they are truly capable of applying such computationally material-driven design.

In a large scale, this approach has led to a shift in architectural practice. Traditionally, as Picon said, making was more synchronous with materials spontaneity30 It dealt with that which Tim Ingold coined as “Textility of Making”, distinguishing textilic nuance of crafts from a nowadays so-called term ‘technical’ or ‘technology’31 . Given the digital era, architects became

24 Bennett, Vibrant Matter, p11.

25 Picon, “Digital Fabrication, between Disruption and Nostalgia.”, p223.

26 Menges, “Fusing the Computational and the Physical: Towards a Novel Material Culture.”, p15.

27 Menges, “Fusing the Computational and the Physical: Towards a Novel Material Culture.”, p15.

28 Amy Frearson, “Armadillo Vault Is a Pioneering Stone Structure That Supports Itself without Any Glue,” dezeen, May 31, 2016, https://www.dezeen.com/2016/05/31/armadillo-vault-block-research-group-eth-zurich-beyond-thebending-limestone-structure-without-glue-venice-architecture-biennale-2016/.

29 Amy Frearson, “Armadillo Vault Is a Pioneering Stone Structure That Supports Itself without Any Glue.”

30 Menges, “Fusing the Computational and the Physical: Towards a Novel Material Culture.”, p225.

31 Menges, “Fusing the Computational and the Physical: Towards a Novel Material Culture.”, p92.

Iqbal Utomo

rarely working on site and only providing a clear set of instructions through drawings32 , separating them from ‘making-process sequences ’ into a mere sight of architecture as ‘thing’33 .

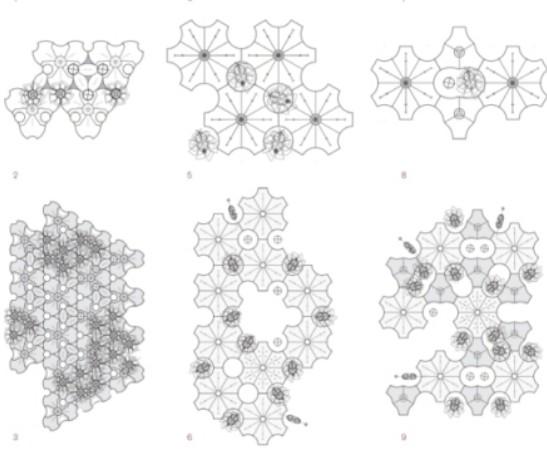

Looking into more detailed, complexity within design eventually let architects or makers use software and build standards. Despite its benefits to make life easier and simpler by avoiding human errors when retracing revised design over documents, creativity matters, and creative designers always attempt to escape standards34 This experimented Hylozoic Ground, regardless of its scale, in which Beesley and his colleagues proposed irregular, customized shapes. Frondlike components, primitive glands, and others were arranged in arrays of thickets and groves in reminiscent of dense-forest creature’s form. Responsive devices of proximity sensors and microcontrollers provided animation due to human presence within the installation. Hygroscopic system and environment fostered them to thicken and look alive as if they were fertile matrix35

32 Scheurer, “Digital Craftsmanship: From Thinking to Modeling to Building.”, p110.

33 Menges, “Fusing the Computational and the Physical: Towards a Novel Material Culture.”, p93.

34 Scheurer, “Digital Craftsmanship: From Thinking to Modeling to Building.”, p111.

35 Beesley and Armstrong, “Soil and Protoplasm: The Hylozoic Ground Project.”, p139-148.

Crafting Non-Standard: Reimagining Materiality's Intrinsic Vitality towards Digital Craftsmanship

36

Crafting Non-Standard: Reimagining Materiality's Intrinsic Vitality towards Digital Craftsmanship

Putting the escaping nuance aside, emerging technologies have been discovered and brought further. Integrated Computer-Aided Design, Engineering, and Manufacturing (CAD, CAE, CAM respectively) balanced that situation and giving mutual benefits between creative designers and design’s performance seekers37 In case of non-standard works, universal machines are then developed to narrow the gap between insufficient or incompatible software and customized shapes by which led to the idea of ‘mass customization’38

Albeit its features of parametrically, customizeably standardized design that let architects become programmers, scriptors, or by Fabian Scheurer ‘toolmakers39’ , it gives problems where architects need to understand the complexity of the design and its procurement or manufacturing approaches by which their algorithms would be situated. Previous algorithms also become obsolete because creative designers are usually determined not to use the same pathways twice. Therefore, digital planning is significant in order to previously and precisely fabricate parts before delivering them into construction site40 . Akin to this solution, Hylozoic Ground, for example, utilized digital computation to reduce material consumption by employing aforementioned form-finding textile system using thin two-dimensional sheets with nested tessellations and shared edges, aimed to reduce waste during digital fabrication41 .

On the other hand, minimal models aiming to condense the real-world complexity into a level in which things can be conceived without build them in real life first is also important, as Scheurer said42:

The art of modeling is based on the ability to sort out, to leave out everything that is not relevant for the given purpose, while including everything that makes a difference.

We could see here that specific purposes enable makers to create multi-scale models43 for certain clients, particularly in large architecture projects. It still needs us to learn to understand each other’s needs (designers, manufacturers, etc) due to interdependencies, especially dealing with the complexity of non-standard projects. Similarly, Hylozoic Ground aforementionedly involved architects and engineers from several countries. Without Beesley mentioning their roles within this project, the importance of collaboration was still shown amongst experts to successfully conceive their poets through this installation.

Akin to what Scheurer mentioned, non-standard projects mean first and foremost defining the interfaces arising from interdependencies between makers. It needs us to concern about the thoughtful and narrative final results whilst balancing the efficacy and efficiency. Thus, it needs experience deeply rooted in practice and a desire to look beyond their own disciplines or the willingness to team up and collaborate, aligning with what Richard Sennett shortly defined that craftsmanship is not described by getting ones’ hands dirty in a workshop, yet by intrinsic motivation to do a job well for its own sake. It requires a combination of material consciousness

37 Scheurer, “Digital Craftsmanship: From Thinking to Modeling to Building.”, p111.

38 Scheurer, “Digital Craftsmanship: From Thinking to Modeling to Building.”, p112-114.

39 Scheurer, “Digital Craftsmanship: From Thinking to Modeling to Building.”, p114.

40 Scheurer, “Digital Craftsmanship: From Thinking to Modeling to Building.”, p114.

41 Beesley and Armstrong, “Soil and Protoplasm: The Hylozoic Ground Project.”, p148.

42 Scheurer, “Digital Craftsmanship: From Thinking to Modeling to Building.”, p116.

43 Scheurer, “Digital Craftsmanship: From Thinking to Modeling to Building.”, p116.

Utomo

in which architects or makers could weaving with them nowadays using emerging technologies and years of practice44 .

Conclusion

New Materialism as a new paradigm in architectural discourse that underpins Hylozoic Ground aims to us embracing and weaving with materials, encouraged by the emergence of digital technologies. Its ability to deal with complex, customized design or non-standard projects could potentially redefine the future of craftsmanship

As a closing, within this context, poetic artworks could be further explored by architects, engineers, experts, ‘makers’, where they are capable of being good craftsmen, as Scheurer wrote45:

Their skills are never going to be replaced, but can be dramatically enhanced by ‘digital tools’.

Acknowledgement

I would like to express my gratitude to Dipl. Ing. [MArch] Clara Jaschke, BSc, MRes as one of DfM lecturers and my tutor for her feedback and reassurance, which influenced how I successfully carried out thissmallresearch.Finally,Iwouldliketothankallthosewhohavecontributedto thisresearch.

Bibliography

AmyFrearson.“ArmadilloVaultIsaPioneeringStoneStructureThatSupportsItselfwithoutAnyGlue.” dezeen, May 31, 2016. https://www.dezeen.com/2016/05/31/armadillo-vault-block-researchgroup-eth-zurich-beyond-the-bending-limestone-structure-without-glue-venice-architecturebiennale-2016/.

Beesley,Philip,andRachelArmstrong.“SoilandProtoplasm:TheHylozoicGroundProject.” Architectural Design 81(November2011):78–89.https://doi.org/10.1002/ad.1215.

Bennett, Jane. Vibrant Matter A Political Ecology of Things. Duke University Press, 2010. https://doi.org/doi:10.1515/9780822391623.

Ingold, Tim. “The Textility of Making.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 34, no. 1 (July 9, 2009): 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bep042.

Menges, Achim. “Fusing the Computational and the Physical: Towards a Novel Material Culture.” Architectural Design. Conde Nast Publications, Inc., September 1, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1002/ad.1947.

Picon, Antoine. “Digital Fabrication, between Disruption and Nostalgia.” In Instabilities and Potentialities, 223–38.Routledge,2019.

Scheurer, Fabian.“DigitalCraftsmanship: FromThinking to Modeling toBuilding.” In Design - AssemblyIndustry, edited by Scott Marble, 110–31. Birkhäuser, 2013. https://doi.org/doi:10.1515/9783034612173.110.

44 Scheurer, “Digital Craftsmanship: From Thinking to Modeling to Building.”, p117.

45 Scheurer, “Digital Craftsmanship: From Thinking to Modeling to Building.”, p118.