12 minute read

Sharing learning on safer care for mothers and babies Ann Remmers, Nathalie Delaney et al

Volume 1, Issue 2 ISSN 2632-363X

Sharing learning on safer care for mothers and babies

Advertisement

Ann Remmers1, Nathalie Delaney1, Heather Pritchard2, Sally Hedge3, Shomais Amedick1 , Julie Edwards4, Dr Anita Sinha4, Anne Baxter4, Kathryn Owen4, Dr K Girish Gowda4, Christina Rattigan4, Charlotte Wallen4, Karin Jones4, Donna Johnson4, Julie Herring4, Dr Smita Sinha5 , Sue Fulker5, Nicky Van-Eerde5, Dr Nicola Johnson5, Lucy Duncombe5, Tracey Sargent6

Abstract or Summary

Maternal and neonatal services operate in a complex and demanding environment, and leaders at all levels should ensure the safety of both staff and the women and babies being cared for. It is everyone’s responsibility to contribute to developing and nurturing a culture that avoids harm, promotes learning whether the outcomes are good or bad, and enables staff to speak up about concerns in order to drive improvement in quality. The national Maternal and Neonatal Health Safety Collaborative (MNHSC) was launched in February 2017 and is a three-year programme led by the NHS Improvement’s National Patient Safety team. The MNHSC aims to: Improve the safety and outcomes of maternal and neonatal care by reducing unwarranted variation and provide high quality healthcare experience for all women, babies, and families across England. The collaborative is structured into three waves, each running April to March. During a 12-month wave there are three phases: diagnosis, testing, and refining and scale up. Trusts receive support from a named NHS Improvement Manager, as well as a safety culture assessment, and three national learning sets (3 days each). There is a national sharing day at the end of each wave. Local units in Wave 2 have shared their learning from quality improvement projects aligned to the national driver diagram, and demonstrated positive impact for mothers, babies and staff across the region. Nationally, results from the culture surveys have been collated to identify themes and actions for improvement in safety culture. Using a structured quality improvement approach has enabled staff working in the maternal and neonatal setting to work together to improve care aligned with the national clinical drivers. Culture will only improve if everyone supports the changes required, and when quality improvement was linked to improvements in safety culture, both the quality of care and culture improved.

1 West of England Academic Health Science Network, NHS England & NHS Improvement, South West Academic Health Science Network,

4 Great Western Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Taunton and Somerset NHS Foundation Trust University Hospitals Plymouth.

Volume 1, Issue 2 ISSN 2632-363X

Introduction

The Maternal and Neonatal Health Safety Collaborative is a three-year programme, launched in February 2017. The collaborative is led by NHS Improvement’s Patient Safety team and covers all maternity and neonatal services across England. The collaborative Methods The Collaborative programme involves all 134 maternal and neonatal units in England. Each unit will participate in one of the three “waves”. Whilst in a wave, units undergo a structured quality improvement process, aligned to the national driver diagram along with a safety culture survey. Nominated improvement leads from each unit build their knowledge of improvement theory by attending nine days of learning sessions during the wave. The driver diagrams and change packages are a resource that maternal and neonatal contributes to the national ambition, set out in Better Births1 of reducing the rates of maternal and neonatal deaths, stillbirths, and brain injuries that occur during or soon after birth by 20% by 2020, and the new strategy sets

Figure 1 – System wide safety programme for Maternal and Neonatal Health

out the ambition for 50% by 2025. healthcare staff can use as part of a systematic improvement approach to improve services for women and babies. The change packages relate to the five clinical priorities outlined in the national driver diagram and set out change ideas, concepts and interventions that can be tested to accomplish the stated project aim. These five drivers are underpinned by a strong focus on safety culture, systems and processes, engaging with staff, women and families, and learning from both error and excellence.

Volume 1, Issue 2 ISSN 2632-363X

Figure 2 – National driver diagram

A network of local learning systems across the country, that brings all providers and network partners together, to work on system level/wide quality improvement has been established. At a local level, units are part of the Local Learning System (LLS). The local learning systems are ‘improvement forums’ where individuals, across different professions and from different organisations, come together to share and learn about the improvement approaches and outcomes. The idea is to create learning systems to encourage the sharing and adoption of good practice. Local Learning Systems provide a further layer of support for organisations to focus on quality improvement, collaboration and an opportunity to reduce variation (and hence inequality) within local geographies, thus enabling maternity and neonatal systems to flourish. Some improvement work, such as smoking cessation, benefit from a system level approach in order to deliver a sustainable solution.

In the South West and West of England, the Local Learning Systems are supported by a faculty, Local Coordinating Group (LCG). Members of the LCG provide coordination of the support and activities across the three waves, including developing the LLS. Members include local maternity system (LMS) leads/ Board representation, the maternity clinical network, neonatal operational delivery network, Patient Safety Collaborative and NHS Improvement.

Volume 1, Issue 2 ISSN 2632-363X

Examples of Quality Improvement projects in the West and South West of England

Swindon

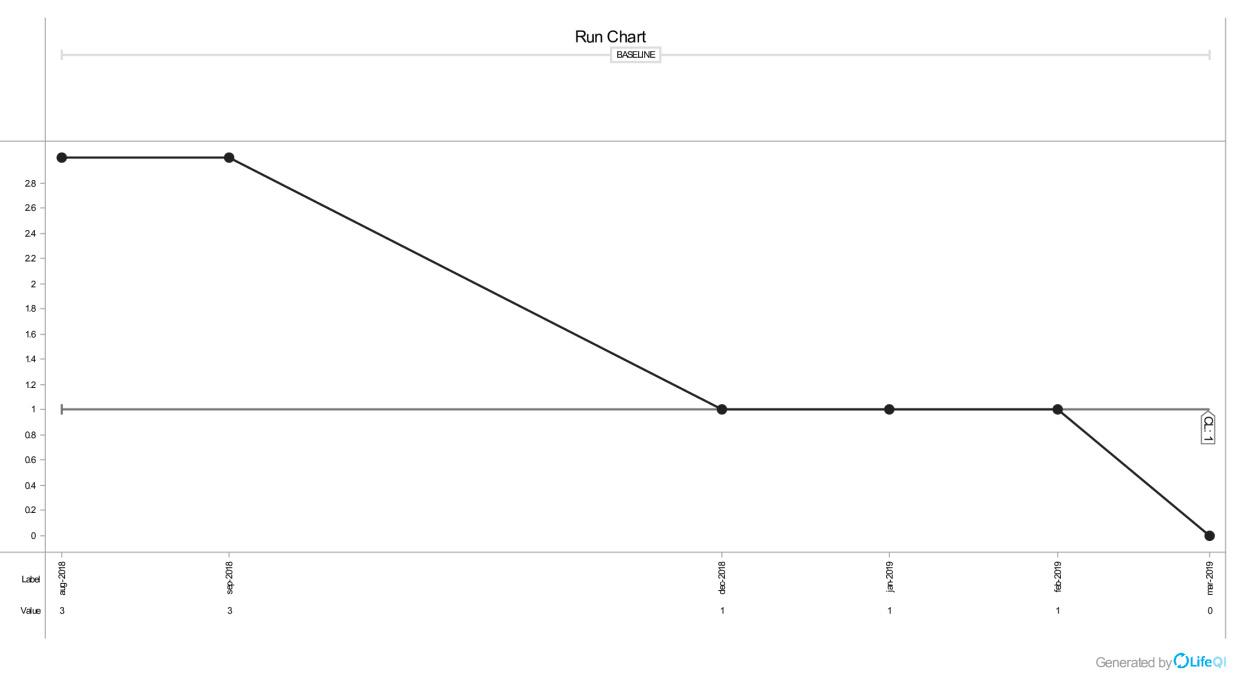

Great Western Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust completed two projects, one focussed on improving the detection and management of diabetes in pregnancy, and the other at reducing neonatal hypoglycaemia. Both projects were presented at the national The neonatal hypoglycaemia project reduced heel tests per baby, and reduced neonatal admission (as seen in run chart above). Staff knowledge and patient satisfaction were measured and results were good. For balancing measures, the readmission rate was nil. Having a clear, structured and easy to understand pathway in place was key learning for the project, along with the learning and sharing day in March 2019. The projects used a quality improvement approach, including PDSA testing ramps, a driver diagram and measurement for

Figure 3 – Great Western Hospital NHS Foundation Trust roadmap for diabetes project

improvement. paramount importance of patient participation. The positive impact of team working, networking and linking into the national programme resulted in the words of the project lead: “happy babies equals happy mums, equals happy staff.”

Volume 1, Issue 2 ISSN 2632-363X

Figure 4 – Great Western Hospital NHS Foundation Trust results for neonatal hypoglycaemia

Plymouth

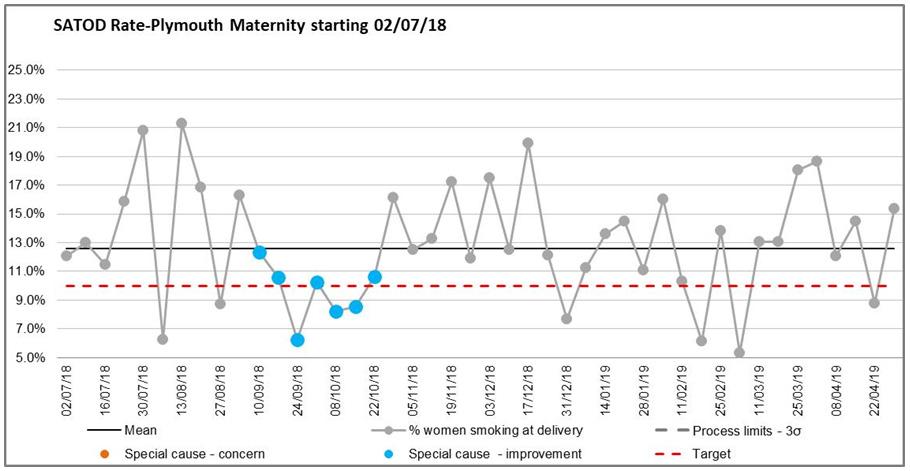

University Hospital Plymouth (UHP) was a pilot site for carbon monoxide (CO) monitoring in 2011, where CO screening was introduced at booking for all pregnancies, but despite this intervention there was no noticeable improvement in smoking at time of delivery (SATOD) rates, with the local performance data regularly recording 16 – 20% of women smoking. The UHP smoking in pregnancy rate has remained high (14 – 18%) due to social health demographics, leaving UHP as an outlier in the south west.

UHP commenced Wave 2 of the Maternal and Neonatal Health Safety Collaborative in March 2018 and were keen to be part of the nationwide programme to improve safety, reliability and the healthcare experience, and to reduce variation in outcomes for women and families. Their change ideas began with understanding the current position and verifying the data recorded in the organisation. The team had a suspicion that the smoking at time of delivery (SATOD) data was not a true reflection, but were confident that all women were being offered CO screening at booking. Some quick audits demonstrated a degree of non-compliance and the limitations in IT data recording systems where the performance (dashboard) data is collated. This information was shared with the wider teams and addressed, where possible, with the education of staff inputting the information and this consequently improved in a short space of time.

Volume 1, Issue 2 ISSN 2632-363X

Figure 5 – University Hospital Plymouth CO monitoring at booking rate

The team implemented an increase in antenatal touchpoints offering CO screening, including on unplanned admission to Triage. The Saving Babies Lives compliance audit illustrated they were not recording the minimum standard of 36/40 smoking status, so the implementation of increased touchpoints began to address this measure, whilst providing a tool for the midwives and obstetricians to have the difficult conversations with women who continued to smoke during their pregnancy. The service did not receive any additional complaints during this time, which was a valid concern from some of the staff. UHP is fortunate to have a close link with Livewell Southwest (an independent social enterprise providing integrated health and social care service for people across Plymouth, South Hams and West Devon), who provide the “Brief Intervention” training to staff which has been in place since 2011 and has provided additional ad hoc training to staff working solely in the acute setting, such as band 7 Delivery Suite Coordinators and Maternity Care Assistants, expanding the knowledge and skills of frontline staff where we were introducing additional CO screening.

The team reported that:

“The three sets of “away days” created the perfect opportunity for us to learn about improvement and the QI methodology, to give us the confidence to just get started, the opportunity to network and share our successes and pitfalls, and to seek help and support where we had encountered challenges. We had met some fantastic and innovative individuals along the way and benefited from engagement with the quarterly Local Learning Sets. Our involvement with the MatNeo collaborative has already contributed to a reduction in the smoking at time of delivery (SATOD) rate to 12%.”

Volume 1, Issue 2 ISSN 2632-363X

Figure 6 – University Hospital Plymouth Smoking at time of delivery rate

Taunton

Taunton and Somerset NHS Foundation Trust focused on the SCORE survey as their improvement project. SCORE: Safety – Communication – Operational Reliability – Resilience – Engagement is an internationally recognised way of measuring and understanding culture in organisations and teams based on the IHI Framework for Safe, Reliable and Effective Care.2 The team designed trust specific communications and had good engagement to achieve a response rate of 71%. Debriefs were held with teams (with support from HR) across the weekdays including early and late times to capture both day and night staff. As a result the team co-designed a driver diagram with an action plan based on the results of the survey with feedback. Suggestions came from all teams, including staffing review, further survey around shift patterns, and celebration of success events, monthly staff meetings, and improved feedback post-incidents. A national publication has been published collating the results from the 87 trusts participating in Waves 1 and 2. 3

Figure 7 – National culture survey results

Volume 1, Issue 2 ISSN 2632-363X

Discussion

Challenges raised by the teams included ‘that time was precious’ in the busy clinical environment and that it could be a challenge to “take time to step back and look at what you are doing when doing the day job”. Involvement from all stakeholders and support from senior leaders helped. The study days were valuable to step outside the workplace and see new innovations and ideas as well as sharing, and to get reassurance that other units had similar challenges and they were not alone.

The key insights from the national culture survey were that how culture is perceived

Conclusions

Maternal and neonatal services operate in a complex and demanding environment, and leaders at all levels should ensure the safety of both staff and the women and babies being cared for. It is everyone’s responsibility to contribute to developing and nurturing a culture that avoids harm, promotes learning from successes and from errors, and enables staff to speak up about concerns and drive improvement in quality. The NHS Patient Safety Strategy Safer culture, safer systems, safer patients4 sets out the need to significantly improve the way we learn, varied widely in maternal and neonatal work settings and roles, reflecting the variable nature of culture. To date this has included insights from over 24,000 staff from a range of disciplines and clinical settings. Leadership was identified as key to involving culture, and leaders need to understand the culture of their organisation to be effective in facilitating improvement. The cultural insights are being used to inform local improvement plans which are being linked directly to quality improvement projects, the summary report identified themes and key actions to support units in improving their culture.

treat staff and involve patients. We have found that using a structured quality improvement approach has enabled staff working in the maternal and neonatal setting to work together to improve care aligned with the national clinical drivers.

Culture will only improve if everyone supports the changes required, and when quality improvement is linked to improvements in safety culture, both the quality of care and culture are improved.

Volume 1, Issue 2 ISSN 2632-363X

Figure 8 – Sign Up to Safety infographic5

To find out more and get involved in the work of the collaborative in the region, visit www.weahsn.net/matneoqi

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the national improvement team at NHS Improvement and the fantastic engagement from participants across units in the West and South West in taking part in the collaborative and local learning systems.

Conflict of interest disclosures

Disclaimers and conflict of interest policies are found at:

http://bit.ly/1wqiOcl

Article submission and acceptance

Date of Receipt: 09.08.2019 Date of Acceptance: 20.10.2019

Contacts/correspondence

Nathalie Delaney, West of England Academic Health Science Network, nathalie.delaney@weahsn.net

Intellectual property & copyright statement

We as the authors of this article retain intellectual property right on the content of this article. We as the authors of this article assert and retain legal responsibility for this article. We fully absolve the editors and company of Patient Safety Journal (PSJ) of any legal responsibility from the publication of our article on their website. Copyright 2020. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

References

1

2

3

4 NHS England (2016) Better Births. https://www.england.nhs.uk/mat-transformation/

Frankel A, Haraden C, Federico F, Lenoci-Edwards J. A Framework for Safe, Reliable, and Effective Care. White Paper. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement and Safe & Reliable Healthcare; 2017. (Available on ihi.org)

NHS Improvement (2019) Measuring safety culture in maternal and neonatal services: using safety culture insight to support quality improvement. Available at https://improvement.nhs.uk/documents/5039/Measuring_safety_culture_in_matneo_services_qi_1apr.pdf

NHS England (2019) NHS Patient Safety Strategy https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/patient-safety-strategy/