7 minute read

ALPINE INSPIRATION

BÉLA BARTÓK’S SWISS CONNECTIONS

Béla Bartók first visited Switzerland in 1908, at the time of his development as a mature artist. Over thirty years later, in October 1940, he travelled through the Alpine country on his final journey to the United States. These two facts illustrate the important role in Bartók’s life played by the Swiss Confederation, where he returned almost annually from 1923 to 1940. Not only did Swiss friends and patrons contribute to the creation of significant works by Bartók, but they also arranged for his manuscripts to be sent to the West, and played a key part in preparations for the composer and his wife to depart for America. By

Advertisement

Zsombor Németh

Bartók came into contact with the Swiss music scene even before he set foot in the country itself. At a concert in Budapest on 13 January 1904, which included the premiere of his symphonic poem Kossuth, the French violinist Henri Marteau also appeared. The charismatic playing of Marteau, who was then also active as a teacher at the Geneva Conservatory, was undoubtedly engraved in Bartók’s memory. In spring 1908, when he came to realise that Stefi Geyer would not perform the violin concerto he had dedicated to her, he turned to Marteau with the idea of presenting the work. (Marteau’s engagements eventually prevented him from including the concerto in his programme, along with the String Quartet No. 1, which was also offered for him to play.)

At this time, Bartók saw great opportunities on the music scene of the Alpine country and, in the hope of a performance, sent freshly composed orchestral pieces to several Swiss conductors – among them Volkmar Andreae, who headed the Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich. Bartók’s efforts resulted in the premiere of the Rhapsody, Op. 1 for piano and orchestra in the spring of 1910 with the composer playing the solo part.

Far From The Noisy Cities

Bartók first visited Switzerland in the summer of 1908: on his journey to the Mediterranean, he stopped in Zürich, Lucerne and Vierwaldstättersee, before travelling on through Geneva. With his first wife Márta Ziegler he twice visited Zermatt and its environs: in summer of 1911 with his composer friend Zoltán Kodály and his wife, and in 1913 to rest on the way home from his field trip to North Africa. In 1927, he spent several months in Davos for the medical treatment of his second wife Ditta Pásztory, and the couple would often choose Switzerland subsequently as a holiday destination.

Surprisingly, however, we read in Bartók’s letters to friends and relatives even on his first trip that he did not feel comfortable in Swiss cities, finding them ‘touristy’, to use today’s parlance. He found peace in pure nature and longed for silence in Alpine villages far from the traffic, and so endeavoured from then on to find smaller places and to stay in simple inns. Excursions and mountain climbing filled him with so much energy that he often began to sketch out new works on these trips. The Swiss mountains inspired both String Quartets No. 3 and No. 4 and the choral work Cantata Profana, while the orchestration of Bluebeard’s Castle was partly completed in the vicinity of the Matterhorn.

Multiplying Visits To Switzerland

Bartók’s first performance in Switzerland took place on 26 May 1910 in Zürich, where he debuted as soloist with his Rhapsody, Op. 1. He most often performed his Piano Concerto No. 2 in the Alpine country, on six occasions between 1934 and 1939 in Winterthur, Zürich, Basel, Schaffhausen, Lausanne and Geneva, under such distinguished conductors as Hermann Scherchen and Ernest Ansermet.

Among Bartók’s concerts in Switzerland, an honoured place was reserved for the chamber evenings where he performed with musical partners for whom he once nurtured especially tender feelings. At the Geneva Conservatory at the end of 1923, Bartók gave a joint concert with the Arányi sisters Adila and Jelly (he wrote both of his sonatas for violin and piano for the latter), while in 1929 and 1930 he appeared with the aforementioned Stefi Geyer in Zürich, Winterthur and Bern. In 1920, Geyer married the Swiss composer, conductor and concert agent Walter Schulthess, who from 1929 emerged as one of the main organisers of Bartók’s concerts in Switzerland.

Folk music also had a role in Bartók’s relationship with Switzerland. In 1933, for example, he published two series of articles in the periodical of the Swiss Workers’ Singing Association, abundantly illustrated with sheet music samples. One year earlier, Three Transylvanian Folk Songs for male choir – an early version of Székely Folk Songs – had appeared in the same publication. In 1938, he gave two lectures for the Musikforschende Gesellschaft in Basel. It is also a mark of Bartók’s reputation in scholarly circles (and public life) that in the summer of 1931 he was the only Hungarian invited to participate in the standing committee on literature and the arts of the League of Nations, based in Geneva.

Commissions From A Patron In Basel

From Bartók’s correspondence, we know that from the 1930s onwards his relationship with his Swiss friends may have been as valuable to him as the physical and mental stimulation he gained from his Alpine sojourns. Among these friends, perhaps the most important was the conductor Paul Sacher, whom Bartók had met at a concert in 1929. Three of Bartók’s most popular and most performed works would emerge as a result of this acquaintance.

In early summer of 1936, Bartók was first commissioned to write an orchestral work by Sacher after the latter had come into considerable wealth through marriage. Barely three months later he completed the masterpiece Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta, which premiered on 21 January 1937 at a concert marking the tenth anniversary of the Basler Kammerorchester.

A few months after the well-received premiere of this work, Sacher ordered another piece from Bartók, this time for a small ensemble, for the Basel section of the International Society for Contemporary Music. The composer proposed a quartet for two pianos and two percussion groups. Doubting whether two percussionists would suffice for the performance of a work placing considerable rhythmic demands upon its performers, he modified the originally planned title to Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion. The highly successful premiere took place on 16 January 1938 in Basel, performed by Bartók and Ditta Pásztory, with percussionists Fritz Schiesser and Philipp Rühlig.

Sacher also commissioned a piece for string orchestra from Bartók, inviting the composer to

Saanen to facilitate its writing. Bartók spent three and a half weeks in August 1939 in a peasant cottage provided to him for this purpose, devoting this time to his music in complete peace. The result was his Divertimento, with some remaining time to complete initial drafts of the String Quartet No. 6. However, the winds of the approaching world war would put an end to this idyll, and Bartók interrupted his stay on 25 August, eleven days earlier than planned, and returned to Budapest before the invasion of Poland. The Divertimento premiered in Basel on 11 June 1940, but the composer was unable to participate.

Surrounded By A Distressing Ideology

Bartók had other important allies in Basel besides Sacher. On several occasions in the 1930s he was a guest of the Müller-Widmanns, married physicians and patrons of the arts, who regularly hosted concerts of his works in their home. The composer would develop a close friendship with Annie Müller-Widmann. As the clouds gathered on the political horizon following the Anschluss in 1938, Müller-Widmann voiced concern over the potential consequences of the rise of Nazism in Bartók’s life, and actively participated in transporting the composer’s manuscripts to the West (as initiated by Bartók himself).

While Bartók enjoyed increasing recognition in the years prior to the outbreak of war, he became more and more occupied with the idea of moving to the United States. His final decision came only with the death of his beloved mother in December 1939, and he promptly wrote to his three most valued friends in Switzerland to inform them in detail of his itinerary. Bartók also requested that they cooperate to secure train tickets for him and his wife for the route from Switzerland through Spain to Portugal, as these were no longer avail able in Budapest. In October 1940, after a laborious journey through Yugoslavia and Italy, the Bartóks arrived in Switzerland. Stefi Geyer accompanied them as far as Geneva, from where they continued by bus through France and Spain to Lisbon. Bartók would see the shores of Europe for the last time from the deck of the SS Excalibur as it sailed from the Portuguese capital on 20 October.

Swiss Legacy

Many of Bartók’s masterworks – including the three important pieces commissioned in Switzerland –found an appreciative audience among the Swiss the most quickly. This is partly due to the receptiveness of Swiss music-lovers to Bartók’s novel musical language. Luckily, the Swiss connection would not be broken with the composer’s passing. His early violin concerto – the score of which lingered unperformed for half a century, to be passed by Stefi Geyer to Paul Sacher not long before her death – was eventually presented at a celebration of Bartók’s music in Basel in 1958 by Sacher and the Basler Kammerorchester, with Hansheinz Schneeberger as soloist. The material took flight to America, which for a time rested in the New York Bartók Archives, before being transferred to the private possession of Péter Bartók (the composers’s second child who passed away in 2020); the work was then passed to and is currently held by the Paul Sacher Stiftung in Basel.

The pianist and composer Nik Bärtsch, a Swiss citizen himself, who first experienced classical music through Bartók, went on to compose a number of works reflecting Bartók’s influence: Rofu and Manta Mantra, for example, a pair of works created in 2012 for two pianos and percussion. His performance at Bartók Spring also pays homage to the Hungarian composer as he and his musical partners present a concert.

5 April | 8pm

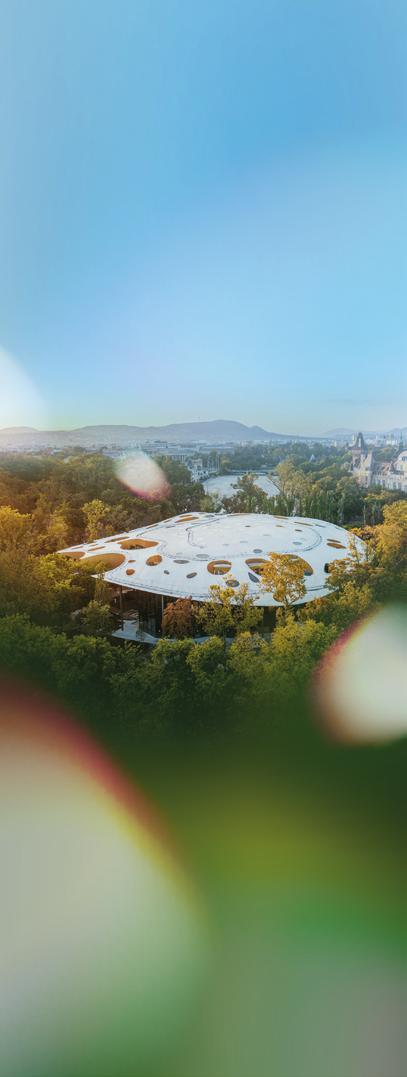

House of Music Hungary – Concert Hall

Nik B Rtsch Reflecting Bart K