3 minute read

REFLECTIONS ON TRANSCRIBING ORAL HISTORY

By Barbara Ann White, NHA Research Fellow

Transcribing oral histories is interesting and challenging. Even if the transcriptions are about people you know, you never fail to learn new things. And the tales about island life will uncover tidbits of history that you never knew.

Transcribing is easier than it used to be because of an automated speech-to-text program. Each oral history is uploaded, and the transcriber reads and listens to each interview simultaneously. The job entails making corrections as you listen. You pause the recording and type in the adjustments. Sometimes, this is not as easy as it sounds because the program prints what it hears, and that may not always be accurate.

People do not always articulate clearly, and voices may drop in volume and become difficult to hear. Background noises can interfere. Sometimes you need to wind and re-wind the recording to distinguish what was said. Good headphones are a must, so the listener can try to isolate the word or phrase that at first seemed unintelligible.

The longer you listen, the more accustomed you become to the particular voice and begin to pick up more words. This may require listening to an entire interview several times to pick up something that you might have missed earlier.

Transcribers need to be familiar with words particular to Nantucket. Place names are often hilariously mangled by digital transcriptions. Examples include the words Sconset, Madaket, and Coatue, which are never transcribed correctly. I listened to one interview several times before I realized that the name was Wyer.

I learn a lot by transcribing and not just about Nantucket. For example, I knew Frank and Bette Spriggs fairly well during their retirement years, but I learned a lot about their rich and fascinating lives before moving to the island. I felt like I got to know them much better by transcribing their 2015 interview with Betsy Tyler.

Francis W. “Franny” Pease told interesting stories about growing up on Nantucket during the Depression. The yearround population was so small that he and his friends could ride their bikes to the beach in the summer, stay all day, and “not see a soul.” He recalled an ice and sleet storm so intense that he skated from school to his home in the middle of the street.

Franny talked at length about his years in the army during World War II. A ham radio enthusiast, he had hoped to be assigned to radio communications. Instead, despite no experience whatsoever, he was assigned to chemical warfare in the Aleutian Islands, which he did not enjoy: “It was nasty stuff.”

He reminisced about the many jobs he’d had on Nantucket and reflected on the changes he had witnessed, mostly about the increase in summer and year-round population.

Frank Spriggs, who “started as a summer kid in 1943,” moved to the island full-time for a portion of his childhood. When he was 10, he enrolled in Cyrus Peirce School, which then housed grades 1–6. The only African American in his grade, he said he was “excited” to be there because the school he’d attended in Washington, D.C., had been segregated.

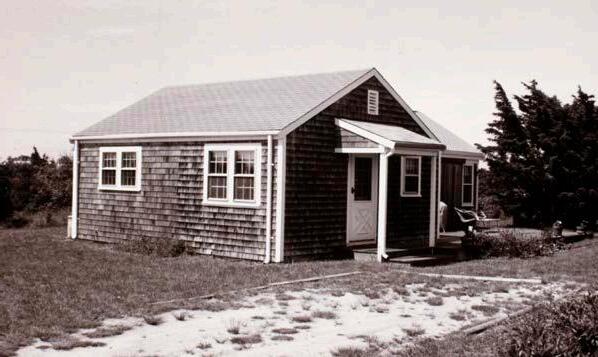

Like Franny, Bette, and Frank described a time when Nantucket was much emptier. Bartlett Road, where they built a house, was a dirt road surrounded by fields with few houses. One neighbor was the nightclub “Thirty Acres,” owned by the Perry family. The Spriggs reminisced about lining up for tickets to dance to live music.

During Frank’s years at I.B.M., they did a lot of international travel, including three years in Japan and a trip to China in the early 1980s. Bette visited the Beijing Zoo when the pandas were a major attraction while Frank was in a business meeting. Frank said that Bette “became the attraction” as a six-foot-tall Black woman. Bette added, “but, not in a hostile way.”

Transcribing interviews is beneficial on several levels. They help the NHA to document local history. They are enjoyable for the people being interviewed who enjoy sharing their stories. And they are learning experiences for both the interviewer and the transcriber.

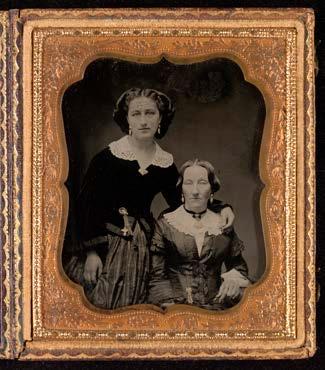

1. Emily F. Coffin Gardner (1836–1906) with an unidentified woman, possibly her mother, Valina Coffin. Sixth-plate ambrotype. PH169 C37.

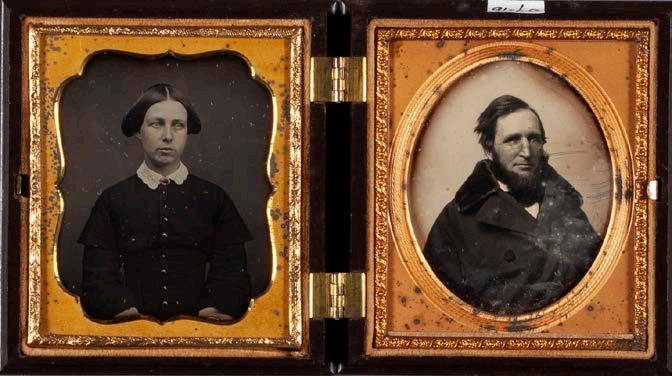

2. Louisa Drew Fisher (1810–1891) and Captain Elisha H. Fisher (1807–1883). Captain Fisher commanded a number of whaling ships, including the Maria and Napoleon of Nantucket. Two sixth-plate daguerreotypes. Gift of the estate of Mary B. Fisher, 1959.16. PH169 C86, C87.

3. Taken as a farewell gift for Emily T. Barnard, 1855. Halfplate daguerreotype. Standing, left to right: Lizzie Crosby, Lizzie Whitney, Helen Pinkham. Sitting, left to right: Susan B. Crosby, Emily T. Barnard, Sarah Howland Gardner. Gift of Helen C. McCleary, RL1999.2004.1. PH169 C224.

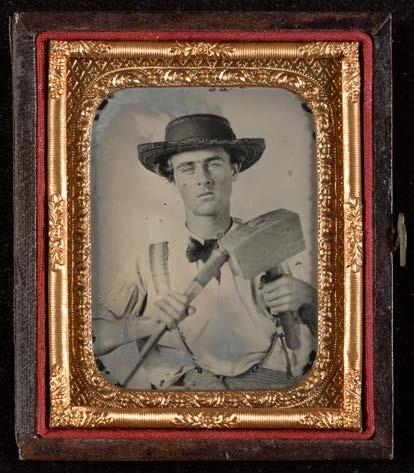

4. Unidentified man holding carpenter’s tools. Ninth-plate ambrotype. PH169 C252.

5. Group on board a ship, circa 1855. Half-plate ambrotype. PH169 C260.

6. Judith Jones Derrick (1836–1912) worked as a teacher at Nantucket High School until she married artist George G. Fish in 1866. Ninth-plate daguerreotype. PH169 C55.