8 minute read

American Whaling on the Chathams Grounds

10

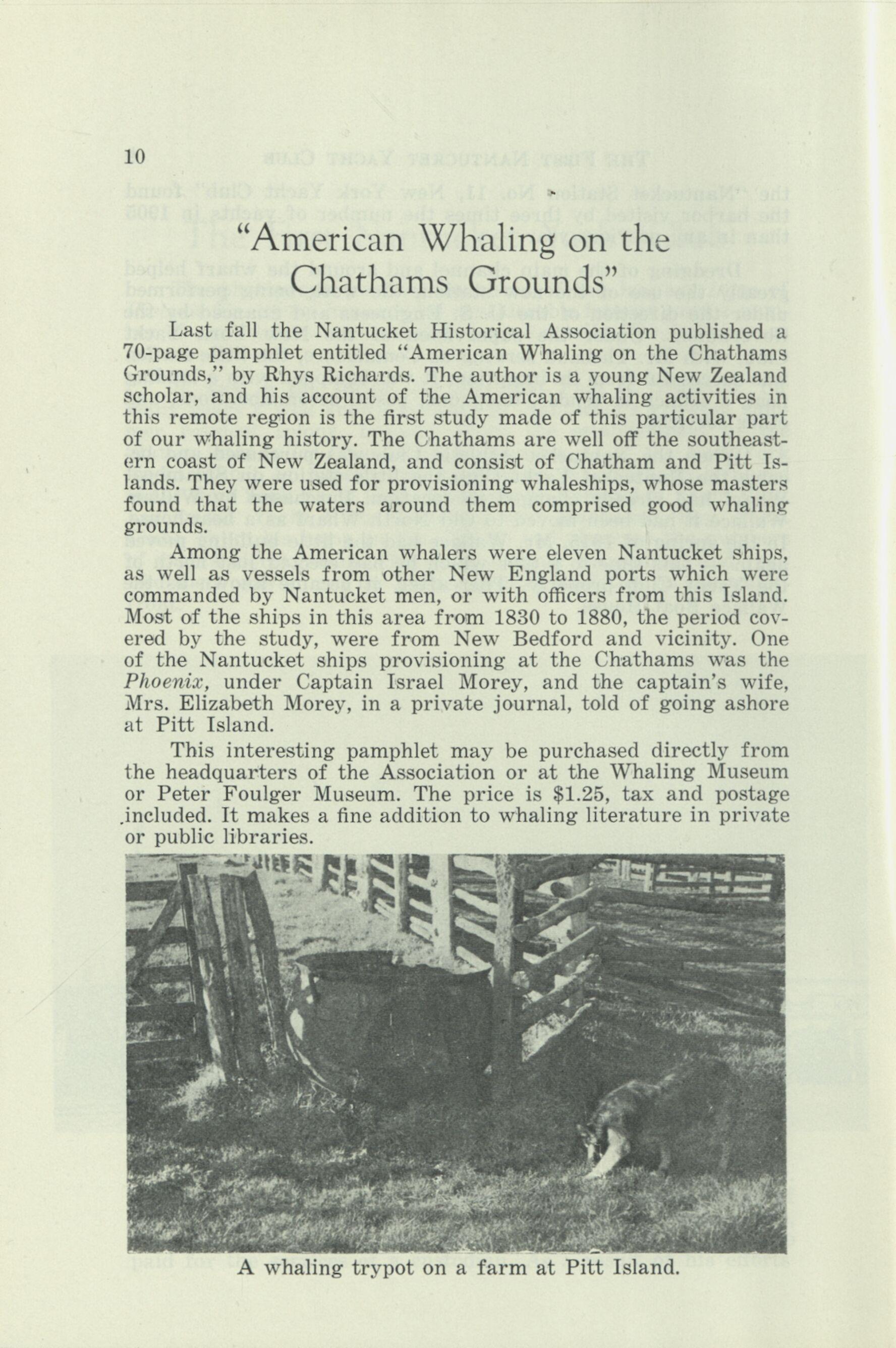

Last fall the Nantucket Historical Association published a 70-page pamphlet entitled "American Whaling on the Chathams Grounds," by Rhys Richards. The author is a young New Zealand scholar, and his account of the American whaling activities in this remote region is the first study made of this particular part of our whaling history. The Chathams are well off the southeastern coast of New Zealand, and consist of Chatham and Pitt Islands. They were used for provisioning whaleships, whose masters found that the waters around them comprised good whaling grounds.

Among the American whalers were eleven Nantucket ships, as well as vessels from other New England ports which were commanded by Nantucket men, or with officers from this Island. Most of the ships in this area from 1830 to 1880, the period covered by the study, were from New Bedford and vicinity. One of the Nantucket ships provisioning at the Chathams was the Phoenix, under Captain Israel Morey, and the captain's wife, Mrs. Elizabeth Morey, in a private journal, told of going ashore at Pitt Island.

This interesting pamphlet may be purchased directly from the headquarters of the Association or at the Whaling Museum or Peter Foulger Museum. The price is $1.25, tax and postage .included. It makes a fine addition to whaling literature in private or public libraries.

11

Headstone Hunting on Nantucket

BY WILLIAM AND ELISABETH BARTLETT GILBERT

Some years ago we discovered the beautiful eighteenth century carving tradition through a study of the work of two carvers who worked in southwestern Vermont. The intricate relief work of Zerubbabal Collins and Samuel Dwight opened our eyes to this early American art form.

On our first visit to Nantucket, in June (we now wonder why we didn't take everyone's advice and visit the island years ago) we drove off the ferry, and asked the policeman at the cross walk half way up Main Street our number one question: "Where is your oldest cemetery?"

At "Old North", with our rice paper and ink and wax blocks, we found what we had only dared to hope would be there — a small but extremely fine selection of all the carvers' styles since 1700.

Our interest in headstones has focused on the eighteenth century. The sculptors — and they signed their work, when they signed it, Sculptor — of that century designed their own symbols, or combined known symbols in unique and individual styles. During the 1700's the oldest carving style gave way to a new, more human approach to death. Both these styles are well represented in "Old North".

As you enter the west section of this old yard, at the central gate, you are immediately among the Bartlett family stones. They are slate stones, with very low relief carving. The principal figure at the top of each stone is the single most characteristic symbol of the earliest tradition — the death's head or skull with wings. This symbol of the Puritans' fear-oriented approach to memorials is found throughout early New England as a powerful expression of the dominant religious doctrine of the seventeenth century. This stark and unadorned symbol can be found from the earliest Plymouth headstones to cuttings in the first decade of the nineteenth century.

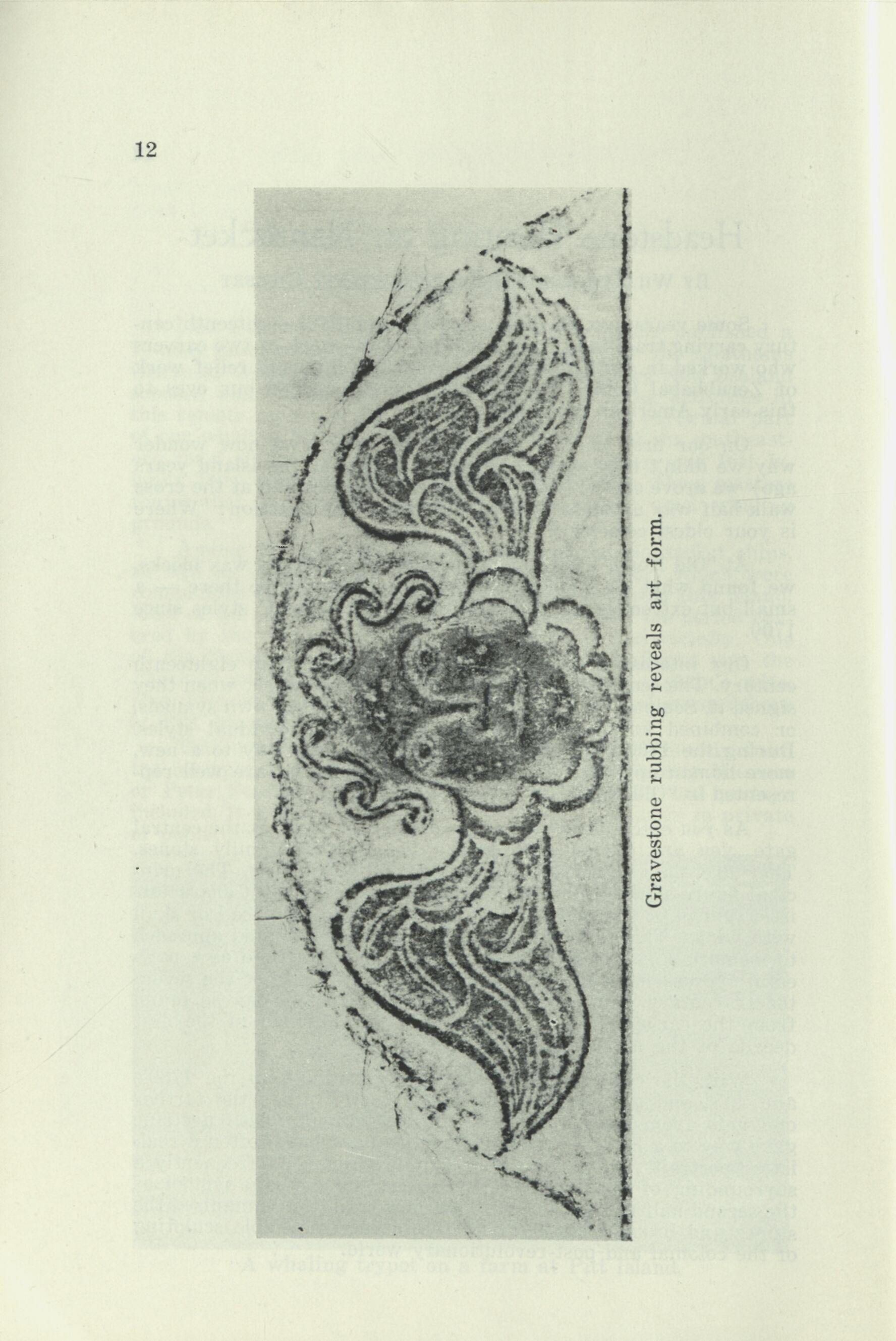

With the coming of the "great awakening", in the 1730's and 40's, and the loosening of religious strictures (the farther one gets from Boston the looser) the fear of death doctrine gave way to a happier image. The humanized head, often a realistic "portrait", with elaborately carved wings and frequently a surrounding of stylized flowers, became the message-symbol of the second half of the century. That new tradition humanized the stones and brought out some of the more remarkable sculpting of the colonial and post-revolutionary world.

HEADSTONE HUNTING ON NANTUCKET 13 "Old North" has two really magnificent small stones in this late eighteenth century style. They stand near the sarcophagus on the hill in the southwest section. Particularly impressive is the Bazeliel Shaw stone of 1770. This stone is tilted forward and is so small it is necessary to get down in the grass to see it. Our half-dozen rubbings of this stone do not fully reflect its superb craftsmanship. Nearby the larger Basilard stone of 1770 is more eroded, but is almost as fine an example of the "realitist" portrait.

Who carved these two unique stones? The slate was imported. Was the carver a local stone-cutter? These excellent works of art survive to remind us of the high level of this little-appreciated American product.

For some reason, stone carving became less individual after about 1815. From that date on for many years most stones were routine representations of urns and willows. The invention and experimentation of the eighteenth century carvers was no longer popular.

"Old North" has a number of magnificent slate stones, some five feet high in which a few artists of the early nineteenth century did succeed in using the stylized patterns with imaginative individuality. In the northwest section, among many fine but unadorned marble stones and some very badly eroded sandstone ones, these elegant and intricately embossed slates are beautiful examples of creative artistry. Two of them are signed, one by Jones of New Bedford, the other by Bagley of Providence. Who can tell us about these fine "engravers of stone", these holdouts against the routinization of individualized art? With the rise of the scrimshaw art of engraving on whale ivory, it would almost have seemed likely that there would have been equal artists in stone on Nantucket. The lack of stone there is probably the greatest single reason for the disappearance of the local, talented, and imaginative stone cutters. Were all these stones imported from the mainland, precut?

The last day of our visit, in September, an old map suggested that we had missed a very special yard — the "colored" cemetery.

We found it, just where it had always been, behind Mill Hill Park, and were at once disappointed and amazed. Disappointed because there were no eighteenth century stones, but amazed at the black sea captains and ministers who lived and worked as members of the Nantucket community long before the Civil War. Since Quakers did not keep slaves, these free men must have been among the first American blacks to establish their individuality in the white world of the island.

Our thanks to Nantucketers past and present for preserving for us Vermonters all these wonders of the island heritage.

16 HISTORIC NANTUCKET

This is a delightful historical novel. — Pennsylvania Inquirer and Courier.

These are, of course, carefully culled, and, as excerpts, wrested from context, but twenty ptt-ans of praise are not to be lightly disregarded in that or any age.

Melville's biographer Raymond M. Weaver is of the opinion that Miriam Coffin "offers perhaps the truest and most vivid picture of life in Nantucket when whaling was at its prime," adding significantly, "It should be better known."5 As a period piece, it is an invaluable document for social history and a memorial to the tastes and attitudes of the times. It is, not least, as Willard Thorp called it, "a readable yarn." 6

In its day, Miriam Coffin rode the crest of the wave of popularity of sea literature, the beginnings of which Cooper confidently ascribes to his own novel The Pilot (1828) in his subsequently appended "Author's Preface" of 1849. As a result of a conversation with a friend who was so transparently uninformed about nautical parlance and procedures as to praise Sir Walter Scott's familiarity with the sea, as evidenced in The Pirate (1822), Cooper was taken with "a sudden determination to produce a work which, if it had no other merit, might present truer pictures of the ocean and ships than any that are to be found in The Pirate. To this unpremeditated decision, purely an impulse, is not only The Pilot due, but a tolerably numerous school of nautical romances that have succeeded it. . . . The Pilot met with a most unlooked-for success. . . . Sea-tales came into vogue as a consequence. . . "7

But Miriam Coffin also struck the reviewers as something original, something American, or better, something originally American. Of the twenty reviewers quoted in the second edition, seven make a proud point of its being an American romance (and not a reprint or imitation of a transatlantic success) : "An American novel is not so common a publication but that we always take one up with more interest than is created by the reprint of some new fiction from the British book market. . . . . not only an original work, but an American book. . . the subject is American. . The words "original" or "originality" appear in seven of the reviews. Whatever the credibility of these reviews, or the substance, it is certainly clear that the new publisher, Harper and Brothers, was urging as particular selling points of the book that it was something excitingly new and different and that it was American in source and authorship.

Hart's own description of Miriam Coffin in the preface to The Romance of Yachting seems, at first glance, a frustrating one. He calls it a "semi-roanance of the sea," which is, to say the least, ambiguous, and he affirms that "it has long been regarded as being closely historical,"8 which is rescued from untruth only