8 minute read

by Edouard A. Stackpole

Nantucket's Role in the Boston Tea Party

BY EDOUARD A. STACKPOLE WHEN THE HISTORIC EVENT known as the "Boston Tea Party" was observed on December 16, 1973, marking the 200th anniversary of the dumping of cargoes of tea into Boston harbor, it also marked an occasion of considerable importance to Nantucket, as two of the three vessels involved in the episode had a direct connection with this island. But another factor insofar as Nantucket was concerned should not be ignored — the role of the young Nantucket merchant Francis Rotch and the effect on this island's commercial relations with London, our chief customer for whale oil and candles.

Early in the summer of 1773 William Rotch, Sr., at his Counting House on Main Street Square, signed the bills of lading consigning two cargoes of sperm oil to merchants in London. The two vessels carrying the oil were the Beaver, of Nantucket, and the Dartmouth, of Bedford. Both were brigs — the Beaver having been built at the Briggs shipyard on the North River in Massachusetts, for William Rotch, and the Dartmouth constructed for the Rotch firm at (New) Bedford — the first large vessel built at this embryo port. Arriving in London early in August the two brigs had no sooner discharged their casks of oil when they sought return cargoes, taking aboard a variety of English goods. But the British India Company, faced with an over-supply of tea, engaged, by governmental sanction, the charter of several vessels to bring the surplus tea to Colonial ports. The Beaver and Dartmouth became two of four vessels engaged to carry chests of tea to Boston, the others being the ship Eleanor, owned by John Rowe of Boston and the ship William owned by the Clarke firm of that city.

The tea-laden vessels did not leave London as a fleet but dropped down the Thames one by one, spending the usual delays in the English Channel, and finally leaving the shores of England behind in mid-October. Before they reached Boston, however, the ship Hayley, owned by John Hancock, sailed into that harbor, and Captain James Scott brought the news that ships carrying the obnoxious tea had sailed from London, four bound for Boston and one each for New York, Philadelphia and Charleston. Aboard the Hayley was Jonathan Clarke, one of the Boston merchants to whom the tea was consigned — the others being Elisha and Thomas Hutchinson, sons of Governor Hutchinson, of Massachusetts, and the firm of Faneuil & Winslow.

Tea was not an obnoxious commodity in Boston and the Colonies. In fact there was a large quantity regularly smuggled into the Colonial ports, but what was detestable was the tax which went along with the sale of the tea to the Colonial Americans. Having been forced to repeal the hated tax measure known

as the Townshend Acts, the British Parliament retained one tax — that on tea — as a token declaration that the Crown had the right to tax the Americans. But the Colonials were convinced that "taxation without representation is tyranny," and they made this their watchword.

First of the "tea ships" to reach Boston was the Dartmouth, under Captain James Hall, dropping anchor inside Boston Light on November 28, 1773, nine weeks from London with 112 chests of Bohea tea below hatches. Francis Rotch, agent for the Rotch firm, came up from Bedford (whether before or after the Dartmouth's arrival is unclear), and went aboard. Rotch had been informed by a committee of Boston Patriots that neither he nor Captain Hall should attempt to enter the brig through customs, but he agreed only as a temporary measure, pointing out that he had only the period defined by law to legally enter the vessel.

Both Francis Rotch and Captain Hall attended meetings of the citizens of Boston in Faneuil Hall and at the Old South Meeting House, during which the assembly unanimously voted that the tea should not be permitted to be landed — that it should be shipped back to London. On the other hand, the Governor's Council, responding to the request of the Clarkes, Hutchinsons and other consignees for governmental protection, voted to place the situation in the lap of Governor Hutchinson. Awrare of the angry mood of the Bostonians these consignees went to Castle William in Boston harbor and placed themselves under the protection of the British troops stationed there.

Caught between the two fires, Francis Rotch (as well as the owners of the other two vessels) agreed to the demand of taking the tea back to London — but under protest.

John Rowe's ship Eleanor was the second vessel to arrive with the tea, coming in on December 3. In the interim the Dartmouth had taken up her anchor and proceeded to a place just off Castle William, where the ships of the Royal Navy, under Admiral Montagu, guarded the roadstead. At this time, under cover of night, a group of 25 Patriots boarded the Dartmouth, obviously to serve as a guard, and prevent the landing of the tea. Rotch at this time "entered" the brig through customs. Had Admiral Montagu seized the Dartmouth at this time and had ordered the tea landed it might have precipitated a pitched battle. The Patriots were in an ugly mood. On the morning of December 1, the Dartmouth again took up her anchor and proceeded to a new position off Griffin's Wharf. Two days later the newly arrived Eleanor joined her. The Patriot guards on the Dartmouth were now in a position to prevent the landing of the tea by the ships' crews.

It was not until December 7 that the brig Beaver reached Boston, under Captain Hezekiah Coffin. Besides having a rough passage, the brig was further troubled by smallpox breaking out

16

HISTORIC NANTUCKET

in the crew. Before she was allowed entry she had to be fumigated while she lay at anchor out in the stream. The fourth "tea ship," the William, never reached her destination, being wrecked on the outer beach of Cape Cod.

Francis Rotch was now acting as the agent of both the Dartmouth and the Beaver. Time was now a factor. According to the King's Customs, the cargoes, after entry into port, must be landed within 20 days, or it could be seized by the custom officials. In this latter case, the consignees must pay the duty. This was precisely what the Patriots did not want to take place.

The other alternative was to obtain a clearance and sail out of Boston with the tea, for return voyages to London, but Governor Hutchinson would not grant such clearance. Thus, placed in an unenviable position of being "between the devil and the deep," Francis Rotch faced the crisis. John Rowe, being a respected Boston merchant, had a sympathetic understanding with the Patriots, but Francis Rotch stood alone. Threats of tar and feathers; threats of burning the vessels; threats of destroying the tea — all were real hazards, but he faced them squarely.

After being refused by the consignees upon his request for payment of the freight charges for the tea, so that a bill of lading could be passed to them, thus placing the responsibility of claiming their shipments, Rotch met with the Patriot leaders again. They demanded he sail the Dartmouth back to London, together with the Beaver, as Rotch had agreed to do under protest. But he could not attempt this without an official clearance; if he had made such a move the Royal Navy would have intervened.

Governor Hutchinson held the key. If he would grant Rotch a clearance the ships could sail — but this was refused. The last day of the period of grace allowed under the law arrived. A mass meeting held in the Old South Meeting House demanded action. Francis Rotch faced them as he had faced the Patriot committees, and consented to make one last appeal from Governor Hutchinson for clearance papers. Through the rain-filled winter night he made the journey by coach to Hutchinson's outof-town house in Milton, and the assembly awaited his return. His confrontation with the Governor was as fruitless as the others had been — he was refused.

When he came back to Boston, and reported the circumstances to the Patriots in Old South Meeting House he gave his account with the full realization of what was to occur — but the courage and dignity of the 22-year-old Nantucketer won the respect of both leaders and assemblage.

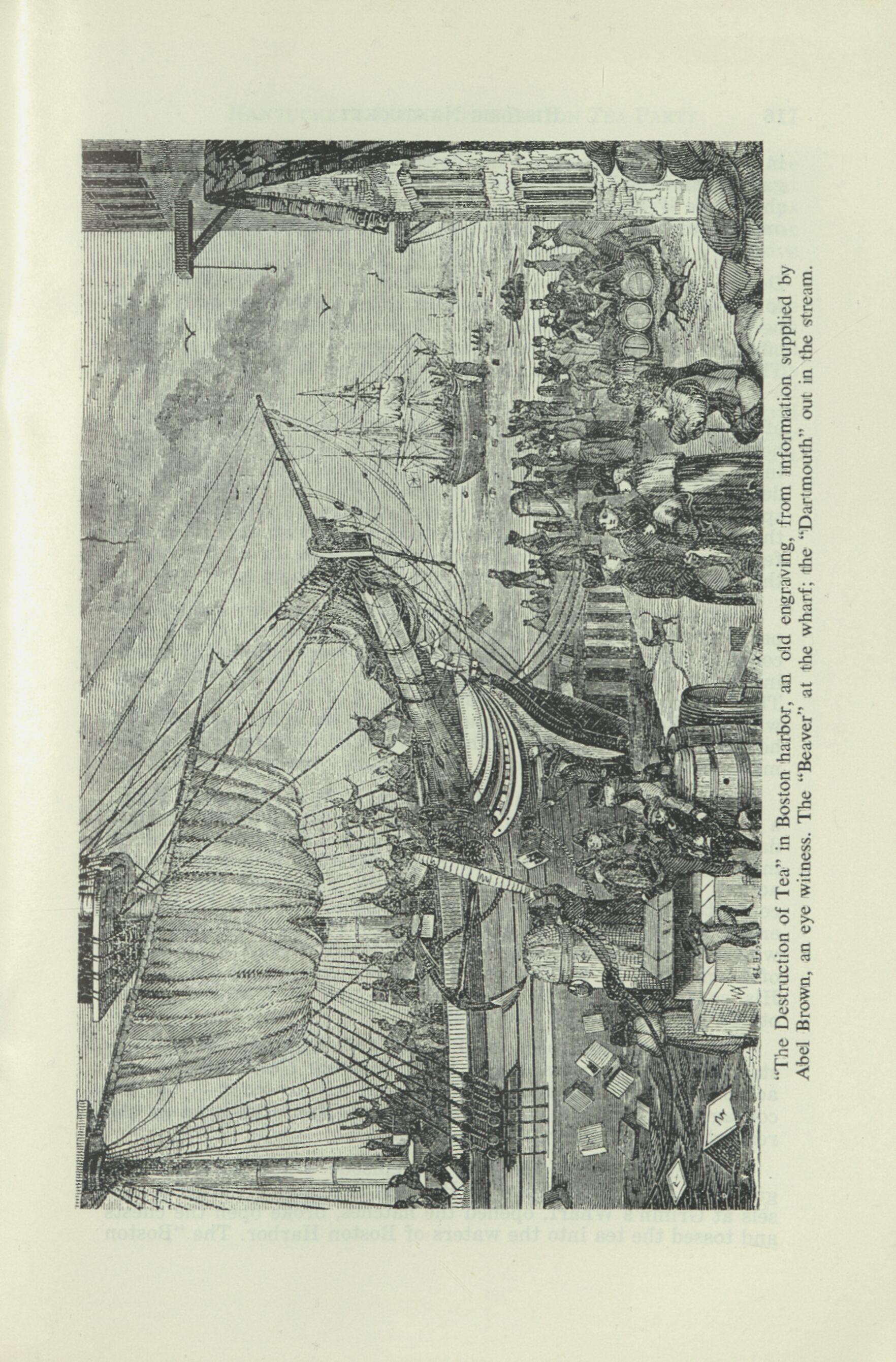

History has fully recorded the episode which followed. Disguised as Indians, a group of Patriots swarmed aboard the vessels at Griffin's Wharf, opened the hatches, broke open the chests and tossed the tea into the waters of Boston Harbor. The "Boston

NANTUCKET'S ROLE IN THE BOSTON TEA PARTY 17

Tea Party" became the prelude for armed rebellion and the American Revolution. But it should be recalled that throughout the final chapter of the "tea troubles" not one of the three ships was damaged. There can be no question but that the manner in which Francis Rotch conducted himself was the decisive factor in this phase of the "Party."

With all the fervor with which historians have reported the significance of the Boston Tea Party the role of Nantucketers may be called but a footnote. However, in light of the critical years that were to come for the island the example set by Francis Rotch has a bearing on attitudes and policies by the whale oil merchants of the town. Through the maintenance of a neutral position they saved not only Nantucket from pillage but they preserved an industry that was to prove a vital economic part of American maritime history.