24 minute read

Her Place in Our Maritime History

T h e U S S N a n t u c k e t N a v y a n d S c h o o lsh ip T a k e s H e r P l a c e i n O u r M aritime H i st ory

by Theodore C. Wyman

IT WAS THAT remarkable event of our Bi-Centennial Year — Operation Sail — which gave people occasion to look back to the days of the sailing ships, and find much of interest. It was over fifty years ago that I spent two years on one of these legendary wind ships, and so I decided to write of that ship before even the memory of the craft joins those companions who have already sailed over the horizon on their way to Fiddler's Green.

There have been several ships in my sea career, but the first of them was the USS Nantucket. I was a cadet aboard her from October, 1923, to October, 1925. When I graduated I passed an examination given by the U.S. Steamboat Inspectors, and received a license for third assistant marine engineer, ocean going, unlimited tonnage.

The USS Nantucket was a three-masted craft, barkentine rigged, and with a steam engine. The propeller shaft could be uncoupled while under sail alone. Because she was originally the USS Ranger, a Naval vessel, she had been bark-rigged, and had served at one time on the China station. Of interest to steamboat men is the fact that her engine, consisting of a high pressure and low pressure cylinder, was mounted horizontally, perhaps to lessen the danger from shell fire. She was a coal-burning vessel, with four Scotch boilers, and I can remember shoveling coal on my first voyage across the Equator.

As the USS Ranger, launched in 1876, she was a gun-boat of 12 guns. After 35 years of Naval service she was loaned to the State of Massachusetts to replace the old schoolship Enterprise, and her name changed to Rockport. In February, 1918, her name was again changed and she became the Nantucket, and during World War I she was a gunboat operating in the First Naval District, as well as serving as a training ship for U.S. Navy Midshipmen. After the War she resumed her role as a Massachusetts training ship, and during a visit to Nantucket in September, 1919, the Town of Nantucket presented her with a new ship's bell, with the name "Nantucket" engraved thereon.

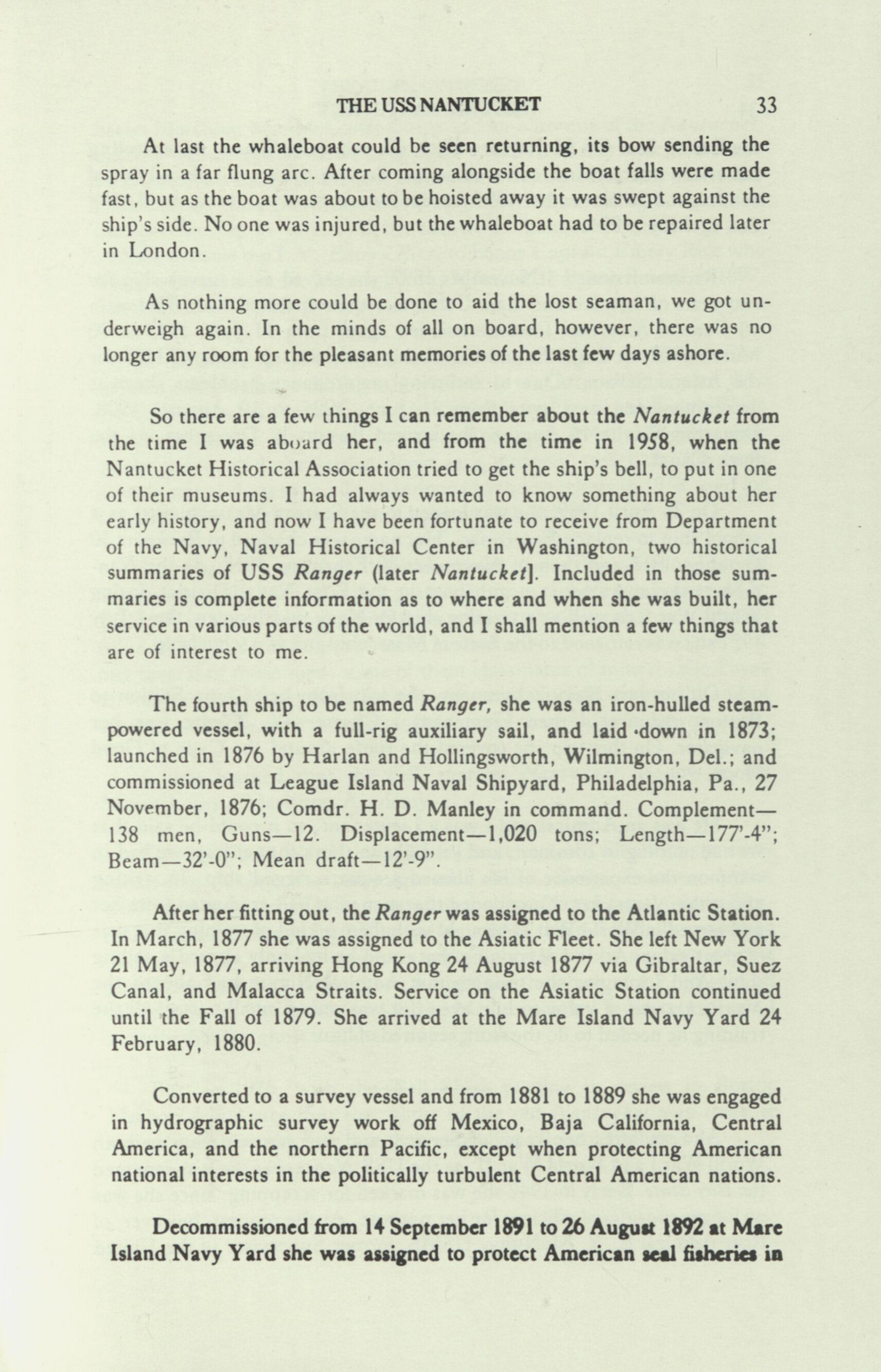

The Nantucket as a bark. When she was first transferred to the Massachusetts Training School the vessel was unde- her original rig as a bark, having been first commissioned as the USS Rasger.

Photo courtesy of the Peabody Museum, Salem.

26

HISTORIC NANTUCKET

It is sad to recall that the old vessel ended her days rather ingloriously. As a part of her career in World War II she was re-named Bay State, and later the Emery Rice, to become a part of the Merchant Marine Academy at King's Point, Long Island, where she became a museum ship until she was finally sold in 1958 to the Boston Metals Company of Baltimore, Maryland, for scrap.

During the time I was aboard the N a n t u c k e t she spent the winter months at North End Park in Boston with a housing built over her. We lived aboard and classes were held aboard ship. The summer months were spent in a cruise to various parts of the world and she visited the following ports while I was aboard her.

1924 1925

Boston — Left 13 May Washington, D.C. Norfolk, Va. Ponta Delgada, Azores Queenstown, Ireland Falmouth, England Rouen, France (Paris) London, England Hull, England Gibraltar Funchal, Madeira Bermuda Provincetown, Mass. Boston — Arr. 20 Sept. Boston — Left 7 May Provincetown, Mass. Ponta Delgada, Azores Funchal, Madeira St. Vincent, Cape Verde Islands Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Bahia, Brazil Port of Spain, Trinidad Bridgetown, Barbadoes Fort de France, Martinique Fredricksted, St. Croix Hamilton, Bermuda Nantucket, Mass. Provincetown, Mass. Boston — Arr. 20 Sept.

The voyages in 1924 and 1925 were what any boy might look forward to, yet might hesitate to take if he knew in advance what that life would be like. There were the times when we had to lay aloft in all kinds of weather to take in or set the sails. Nights with a gale blowing, and rain pouring down, it was supposed to be "one hand for the ship and one hand for yourself', but most of the time two hands were needed to handle the sails. It was a hard life and at the same time it was a wonderful life as we were back in the days of the old sailing ships.

During those voyages I saw for the first time many new countries and islands. On the voyage from the Cape Verde Islands to Rio, I crossed the Equator and met King Neptune, to become one of his trusted shellbacks.

For this reason, and because I had served on square-rigged ships, I was able later to join the "Square-Rigger Club" of San Francisco.

In 1924 we covered 10,964 miles, and in 1925 12,600 miles. Although I do not know how fast we were going when, toward the end of a summer cruise, we had a race with a lighthouse tender, I am sure that we must have been going at around ten knots. (And of course I am sure that we must have won the race). Our Chief Engineer had served aboard that lighthouse tender and was very much interested in the race we were having.

I can remember one more time when we were really moving through the water and I shall include here an entry from the log I kept during the cruise of 1925. Not of any great importance, but it can add to a picture of life aboard a sailing ship.

"Friday, July 24, 1925

The wind still holds good over the starboard quarter and the night is one of the most beautiful I have ever seen. We are just below the Equator enroute from Bahia to Trinidad with all sail set, including the stunsail, and are listed to port as we rush through the water. A cloudless sky is alive with brilliant stars and the Southern Cross is flaming off our port beam. It is cool on deck after the heat of day and a new moon is flooding the sea with light and making the foresails gleam like silver."

Crossing The Equator

Because of numerous magnetic Equator surveys she made, Ranger received the reputation as the ship that had crossed the Equator more' times than any other then afloat. She must have been an old friend of King Neptune.

The Equator. What a power of suggestion there is in those two words! They bring to mind the proud clippers that in their day went rolling down to Rio and around the Horn to China and India, battered tramps knocking about from port to port, the doldrums and schools of flying fish. They bring, too, the glory of the Southern Cross, whose home is in those latitudes and the traditional observance of "crossing the line". The custom is when a ship crosses the Equator, for all those who have never crossed the line to be initiated into the "Ancient and Honorable Order of the Deep" by King Neptune and his court.

June 15, 1925 in latitude 00000 and longitude 27 degrees west we approached the Equator, southward bound from the Cape Verde Islands to Rio de Janeiro. The day was fair and clear with a light breeze that did little to ease the equatorial sun that beat down on us. Large schools of. flying fish, their wings gleaming in the bright sunshine, skimmed over the smooth surface of the sea and an expectant hush hung over the ship.

"Davey Jones" had come aboard the night before to present the Captain with a summons from King Neptune which commanded all hands to appear at his court to be held under the Equator the next day. Now King Neptune and his royal party of Queen Aphrodite, court pages, doctor, barber, policemen and bears came aboard, a salute of twenty-one guns was fired and the Jolly Roger was unfurled at the mizzen truck. The royal party was received by the Captain on the quarter deck where he turned the command of the ship over to King Neptune and then escorted them to chairs on the bridge which overlooked a tank made from a large canvas awning.

One by one we ascended to a platform that extended out over the tank and there we received a shave with a large wooden razor in the none too gentle hands of the court barber. The shaving cream was a mixture of sulphur, molasses, mustard, flour and water, and was applied with a big paint brush, care being taken that a large portion entered one's mouth and ears. Then came a very bitter pill from the court doctor which had to be chewed, swallowed and washed down with a drink of salt water before a backward dive, forcibly executed, was made into the tank and the welcoming arms of the four bears who finally threw us out on deck after a whole hearted ducking.

We had been gathered to the fold as trusty shellbacks and duly initiated into the solemn mysteries of the Ancient Order of the Deep. We were now full fledged sons of King Neptune and our Neptune diplomas, signed by Neptunus Rex, Lord of the High Seas, certified that we had crossed the Equator and were now good seamen, and commanded all his subjects to pay us due respect wherever we might go.

And now a copy of the wording on my Neptune Diploma.

Domain Of Neptunus Rex

To all sailors wherever ye may be, and to all Mermaids, Sea Serpents, Whales, Sharks, Porpoises, Dolphins, Skates, Eels, Suckers, Lobsters, Crabs, Pollywogs and other Living Things of the Sea.

Greeting: Know ye: That on this 15th day of June, 1925 in Latitude 00000 and Longitude 27 degrees W, there appeared w i t hin t h e l i m i t o f O u r R o y a l D o m a i n t h e U . S .S . N a n t u c k e t , bound southward for the Equator and South American Ports.

BE IT REMEMBERED that the said Vessel and Officers and Crew thereof, have been inspected and passed on by Ourself and Our Royal Staff. And Be It Known: By all ye Sailors, Marines, Land Lubbers and others who may be honored by his presence that Theodore C. Wyman having been found worthy to be numbered as ONE OF OUR TRUSTY SHELLBACKS has been gathered to our fold and duly initiated into the

Solemn Mysteries of The Ancient Order of The Deep.

The Watch On Deck — At Sea.

There are many memories of my voyages aboard the N a n t u c k e t , and among the most lasting include my recollections of a regular part of the ship's routine — the watch on deck. Only those who have shared the experience may appreciate it fully. Along the gun deck, from the after hatch to the well forward under the forecastle hatch, swung the hammocks of the cadets. They had a ghostly look in the faint light of the standing lights. The noise on deck sifted below as a confused murmur of familiar sounds. Now and then came a muffled crash as a sea came aboard or surged against the dogged gun ports. Some of the hammocks swayed lightly with each roll of the ship while others in which men were asleep swung in a slower and steadier arc. At times they touched the overhead, so violent was the motion of the ship, yet the sleep of the men remained undisturbed.

On deck the bo'sn's mate clung to the railing at the foot of the bridge ladder as he waited for word from the bridge to turn out the watch below. It was nearly eleven-thirty and the watch on deck was anxious to be relieved so that it could turn in and get a few hours of sleep. The shaking of the bridge ladder as the orderly on watch started to descend roused the bo'sn's mate and he glanced up to see in the shadowy murk the shoulders and sou'wester of the officer of the watch leaning over the bridge rail.

"Turn out the watch", floated down the command and the bo'sn's mate lurched aft as the tolling of the ship's bell died away before it was scarcely born.

30

HISTORIC NANTUCKET

The gun deck was flooded with a sudden glare of light and the strident cry of turn out the watch, turn out all the port watch roused the sleeping men. Then the bo'sn's mate made his way along the gun deck shaking each hammock to make sure that every man was awake before he returned on deck.

Here and there an arm appeared, then a leg, as blankets were thrown aside and all along the gun deck men were sliding out from their hammocks. They swayed dizzily for a moment as they clung to their hammock lashings while trying to come awake. Then they jambed themselves between bulkheads and lockers or anything that offered some support as they pulled on woolen shirts, pants and sweaters and over them coaxed oilskins and boots until they were practically watertight. Sleep closed in on them instantly as they sprawled out on deck waiting for eight bells to strike, but they were awake and staggering toward the midships ladder at the first shrill note of the bo'sn's pipe as the hoarse bellow of lay aft to muster all the port watch floated down the hatchway.

The wild fury of the wind greeted them as they advanced to the quarter deck alternately trotting down the sloping deck with short, mincing steps and laboring sharply upward as the ship buried her lee rail in the swirling foam. They lined up in some semblance of order and at times the whole line swayed sharply forward, then leaned back until it seemed about to topple over. Two men pitched forward and rolled across the deck to bring up with a crash against the lee bulwarks as the port rail was flung crazily skyward. Then they made their way sheepishly across the rolling deck as the bo'sn's mate passed the word to relieve the wheel, lookout and lifebuoy and for the lifeboat watch to turn in between the after hatch and the mizzen mast.

With one arm flung around a mizzen shroud and the other hand grasping it, the man on lifebuoy watch stood ready to release the lifebuoy hanging over the ship's side in case anyone went overboard. JHle was safe from the dangers of the reeling deck and could enjoy the wild fury of the storm, the rising and falling song of the wind in the rigging and the ifiountainous seas that came rushing up from astern, rising until their curling grey tops seemed about to crash down and bury the ship. No canvas was spread and the ship was driving before the storm under steam alone. Now and then the wild thrashing of her propeller could be heard as it came out of the water and a man stood ready in the engineroom to slow down the engines when they started to race.

On the other side of the deck stood the lifeboat watch ready, at an instant's notice, to turn out the lifeboat crew asleep under a canvas between the after hatch and the mizzen mast, while the officer on duty stood his watch on the bridge behind a weather cloth from where he could see both forward, aft and aloft. The helmsman took no notice of the spray that continually swept over him and was conscious only of the swinging compass card in the glowing interior of the binnacle and of keeping the ship on her course. Safe from the worst of the wind and spray, the watch on deck made themselves as comfortable as possible on the fiddly hatch behind the forward deck house under the bridge. Heat from the fireroom below washed over them in comforting waves and there would be no sail to handle as long as the gale continued. No racing for the topgallant yard where the sail was so much easier to handle than on the topsail yard and no laying out along the yardarms to fist in the iron hard canvas in the_ reeling, pitching darkness.

Aft on the poop deck, the lifebuoy watch sensed the approach of two bells, one o'clock, and strained forward to hear the ship's bell as the hour was struck. The sound of the bell was whipped away by the gale before it reached him, but he knew the hour had struck as he made out the dim figure making its way aft to read the log. He waited until the ship ceased rolling for a moment before releasing his hold on the shrouds to make a staggering rush forward to report his post and the stern light to the bridge. Luck was against him as a sea came over the stern and washed him along the deck until he brought up sharply in the scuppers beneath the main mast shrouds.

I

Later, as the hours slipped by, the man on lifebuoy watch became drowsy, but caught himself in time and released his hold on the shrouds for a moment until the exertion of keeping on his feet brought him fully awake. Then at last the watch was relieved and the men tumbled below to the safe haven of their hammocks and hardly had time to settle themselves before they were asleep. Some time later the sound of hoarse shouts and scuffling feet on deck roused for a moment the man who had been on lifebuoy watch. "The wind must have dropped" he thought. "They are setting the sails."

We had slipped our moorings at Rouen, France, and as we threaded our way down the Seine our thoughts turned back to the days just past that had been spent in Paris. No one suspected that within a few brief hours one among us would be gone.

From noon to early evening the everchanging beauty of the Seine slowly unwound before us. Every turn in the river brought into view a scene more charming than the one preceding as tiny villages or smaller groups of white-fenced cottages slipped by.

At last the river began to widen, and by dusk we had entered the harbor of Le Havre and were once more breasting the green rollers as we set our course across the Channel. It was good to feel the roll of the ship's deck under our feet again after more than a week inland.

It became dark early, for the sky had become overcast. The gentle breeze of early afternoon had strengthened, and the choppy sea that had risen gave promise of a wet crossing to the English coast. There was work to be done, however, and as the murky lights of the harbor began to fade cargo lights were rigged amidships, and the watch on deck began to take in the gangway ladder that was still over the side. A block and tackle had been rigged to the small platform to which the gangway ladder was attached, and on this platform, with a heavy capstan bar in his hands, a member of the crew was endeavoring to work the gangway ladder loose from its moorings. In some unaccountable manner the gangway platform on which the seaman was standing raised up, the iron supports came loose from their sockets, and the seaman was instantly plunged overboard.

As the cry of "Man Overboard" hurtled aft through the sudden hush the man on lifebuoy watch sprang into action and a lifebuoy, its flare casting a lurid glow on the surrounding sea, began to drift astern, while a jangling bell in the engineroom told that the officer on the bridge had responded to the emergency. All hands were piped on deck and the scream of the boat falls tore the air as the whaleboat was lowered away.

As the whaleboat pulled away, everything was made ready aboard to assist the seaman should he be recovered, and to hoist the whaleboat back to its davits. From the bridge a searchlight pointed an inquiring finger hither and yon, but merely succeeded in illuminating the scudding foam of a rising sea. Leadsmen in the chains droned out the harbor depth from time to time as there was danger of going aground. Over the ship hung an air of foreboding, for all hands aboard realized the danger that the seaman was in.

For two hours the fruitless search was continued, but the darkness, the wind and the choppy sea defeated the would be rescuers. Possibly the heavy capstan bar had crippled the seaman as he fell.

THE USS NANTUCKET

33

At last the whaleboat could be seen returning, its bow sending the spray in a far flung arc. After coming alongside the boat falls were made fast, but as the boat was about to be hoisted away it was swept against the ship's side. No one was injured, but the whaleboat had to be repaired later in London.

As nothing more could be done to aid the lost seaman, we got underweigh again. In the minds of all on board, however, there was no longer any room for the pleasant memories of the last few days ashore.

So there are a few things I can remember about the Nantucket from the time I was aboard her, and from the time in 1958, when the Nantucket Historical Association tried to get the ship's bell, to put in one of their museums. I had always wanted to know something about her early history, and now I have been fortunate to receive from Department of the Navy, Naval Historical Center in Washington, two historical summaries of USS Ranger (later Nantucket]. Included in those summaries is complete information as to where and when she was built, her service in various parts of the world, and I shall mention a few things that are of interest to me.

The fourth ship to be named Ranger, she was an iron-hulled steampowered vessel, with a full-rig auxiliary sail, and laid -down in 1873; launched in 1876 by Harlan and Hollingsworth, Wilmington, Del.; and commissioned at League Island Naval Shipyard, Philadelphia, Pa., 27 November, 1876; Comdr. H. D. Manley in command. Complement— 138 men, Guns—12. Displacement—1,020 tons; Length—177'-4"; Beam—32'-0"; Mean draft-12'-9".

After her fitting out, the Ranger was assigned to the Atlantic Station. In March, 1877 she was assigned to the Asiatic Fleet. She left New York 21 May, 1877, arriving Hong Kong 24 August 1877 via Gibraltar, Suez Canal, and Malacca Straits. Service on the Asiatic Station continued until the Fall of 1879. She arrived at the Mare Island Navy Yard 24 February, 1880.

Converted to a survey vessel and from 1881 to 1889 she was engaged in hydrographic survey work off Mexico, Baja California, Central America, and the northern Pacific, except when protecting American national interests in the politically turbulent Central American nations.

Decommissioned from 14 September 1891 to 26 August 1892 at Mare Island Navy Yard she was assigned to protect American seal fisheries in

34

HISTORIC NANTUCKET

the Bering Sea. On 31 January 1894, she relieved Alliance in protecting American interests in Central America. Service there until placed out of commission 26 November 1895, except for temporary duty in the Bering Sea in May, 1894.

Recommissioned 1 November 1899, she served as a survey ship for two years off Mexico and Baja California, then operated with Wisconsin off Central America. Decommissioned again from 11 June 1903 to 30 March 1905, at Puget Sound Naval shipyard, she left 16 April 1905 for the Asiatic Station. Due to recurring maintenance problems she was decommissioned at Cavite from 21 June, 1905 to 10 August, 1908. Departing Cavite 16 August, she arrived Boston 12 December via the Suez Canal.

On 26 April 1909, she was loaned to the State of Massachusetts as a school ship to replace Enterprise. Her name was changed to Rockport 30 October, 1917 and then to Nantucket 20 February, 1918. As the Nantucket, she operated as a gun boat in the First Naval District during World War I, as well as a training ship for Navy midshipmen. On 1 July 1921 she was returned to the State of Massachusetts as a schoolship.

On her last Navy assignment, the trip from her China Station to Boston, Admiral - then Lieutenant - Chester W. Nimitz was her navigator. On this trip she covered the route around the Cape of Good Hope.

He was an Admiral and I was a Lieutenant, so it could be said that we had nothing in common, and yet I like to think that at least we had in common the experience of life aboard a square rigged ship. In writing about the Nantucket, I mentioned that men who had graduated from her and served in World War II brought with them a kind of training that was of great value. A kind of training that could be had only aboard a sailing ship. And I imagine the training that Admiral Nimitz had aboard the Nantucket was of value to him even if it was only a small part of all the training he needed to do the work required of him.

And so, after her years of Service, and her participation in both World War I and World War II, as the USS Nantucket she was renamed the Bay State. Early in 1942 she was marked for scrapping, since she was no longer considered efficient for her purpose. At the request, however, of Rear Admiral R. R. McNulty, USMS, former Supervisor of the United

States Merchant Marine Cadet Corps and an alumnus of the Nantucket, the ship was assigned as a training vessel to the Academy which had been established at Kings Point just six months before. The Bay State left Charlestown Navy Yard under tow 21 July, 1942, arriving Kings Point the next day. On 31 July, 1942 her name was changed for the fourth time and she became the I. V. Emery Rice, to honor Captain Emery Rice who was graduated from the Massachusetts Nautical Training School in 1897, the days of the USS Enterprise.

In the winter of 1943, while on a training mission, the Emery Rice suffered some damage during a hurricane. It was after this incident that the Emery Rice was brought to a berth at Mallory Pier at the King's Point Merchant Marine Academy. It was in February, 1944, that her active career ended, and she settled down as a museum vessel. As has been already stated she was finally abandoned to the wreckers in 1958, sold for $13,600, and towed to the junk-yard at Baltimore.

It can be truly said that under her varied names this vessel had served her country well. Men who had graduated from the Nantucket served in World War II and brought with them a kind of training that was of great value. A kind of training that could be had only aboard a sailing ship. I met several of those men, some of them classmates of mine, while I was serving as a boarding officer for convoys out of Norfolk toward the end of the war, and they were the captains of some of those ships in convoy.

I have learned that the bell, marked Nantucket, is now at the Massachusetts Maritime Academy.

During World War III was First Lieutenant of LST 197 from commissioning through the campaigns of Tunisia, Sicily, Salerno, Anzio, and Normandy. In 1974 I returned to the Far Shores for a visit to Normandy and Anzio and the Military Cemeteries there. I had always hoped that, some day, I could return on what I thought of as my own private pilgrimage and that, while there, I might see the ghost of my old ship off the beaches at Normandy and in the Mediterranean. I did return and I am sure that her ghost was there waiting for me.

But, in 1976, with the Tall Ships passing in review in Boston Harbor, I am sure that the ghost of the old Nantucket was there to revie,w them to make sure that they were all in "Bristol Fashion".

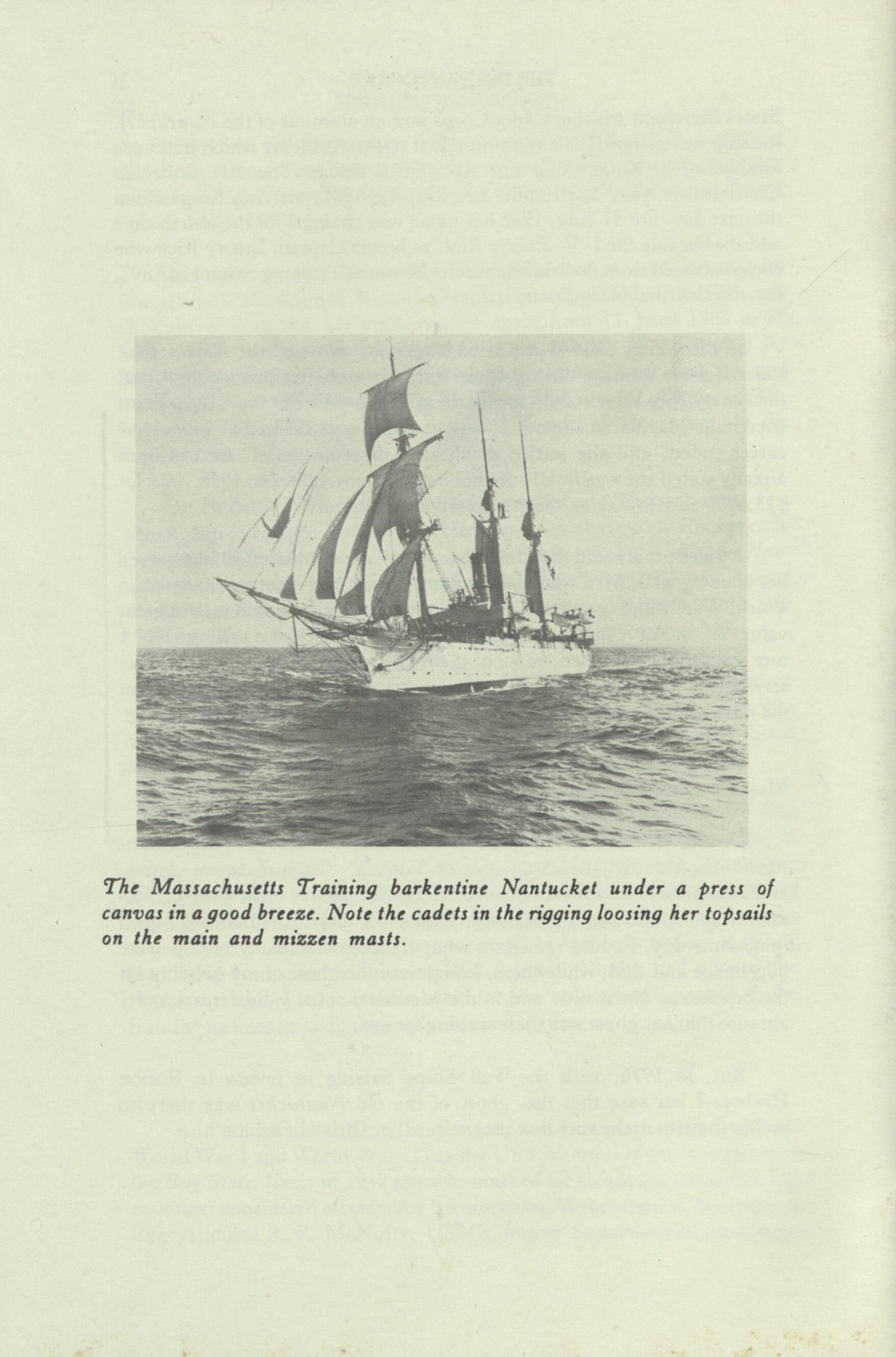

The Massachusetts Training barkentine Nantucket under a press of canvas in a good breeze. Note the cadets in the rigging loosing her topsails on the main and mizzen masts.