5 minute read

Oliver S. Chase, a Young Nantucketer "In Search of

18 " Ol i v e r S . C h a se , a Y o u n g N a n t u c k eter i n S e a rc h o f W e a l th a n d A d v e n t u r e"

by Andre Aubuchon

(Conclusion of an article begun in our April issue.)

THERE CAN BE few more touching spectacles than that of a young man, almost alone in a distant country and bound by honor and duty to remain for a long time. So overwhelmed was Oliver by homesickness and by his environment that he wrote openly to his brother-in-law, Josiah Barrett, of his hope that a revolution or a Spanish invasion would so disorganize Peruvian commerce that it would be possible for him to break his agreement with Sylvanus Crosby without dishonor.

"How I should like to be with you," he wrote to Lizzie, "But, as Balm (Josiah) says, 'If wishes were horses beggars could ride.' — In which case I should turn my horses to the North Pole." In December, 1866, Oliver wrote: "While I do not yet see any prospect of so early a return, still as time is continually working changes...we may hope, though circumstances do not warrant a definite expectation."

Contributing to Oliver's homesickness was the bitter realization that he had been unable to save enough from his salary to start a business when he would return to New England. Oliver's faithfulness to the word he gave to his employers and his sense of utter desolation showed in one of his letters:

I can assure you that I do not like it at all to be so far away from home. Was I gaining any material advantage through my being here, the fact of my being so far away might be somewhat reconcilable, that might be - Aye!, undoubtedly would be of far more advantage to me every day if in the States among my own people...Obliged to stop here...I may yet build up an antidote to this noxious poison.

Oliver consoled himself by reflecting upon his good fortune in enjoying almost perfect health. In almost every letter, he alluded to this

OLIVER S.CHASE 19

blessing. Even if separated from loved ones and unable to save from his salary, he knew that he would be only twenty-six when he returned to the United States. A bright future awaited him with his ability, experience, and health. In July, 1867, Oliver had written: "Yes, I have been favored as regards health...for which great blessing I feel most thankful." With such good health and a long life ahead of him, Oliver was consoled by that most powerful drug, hope: "However, I may yet have my day," he wrote to his sister, and these words might well stand as his motto.

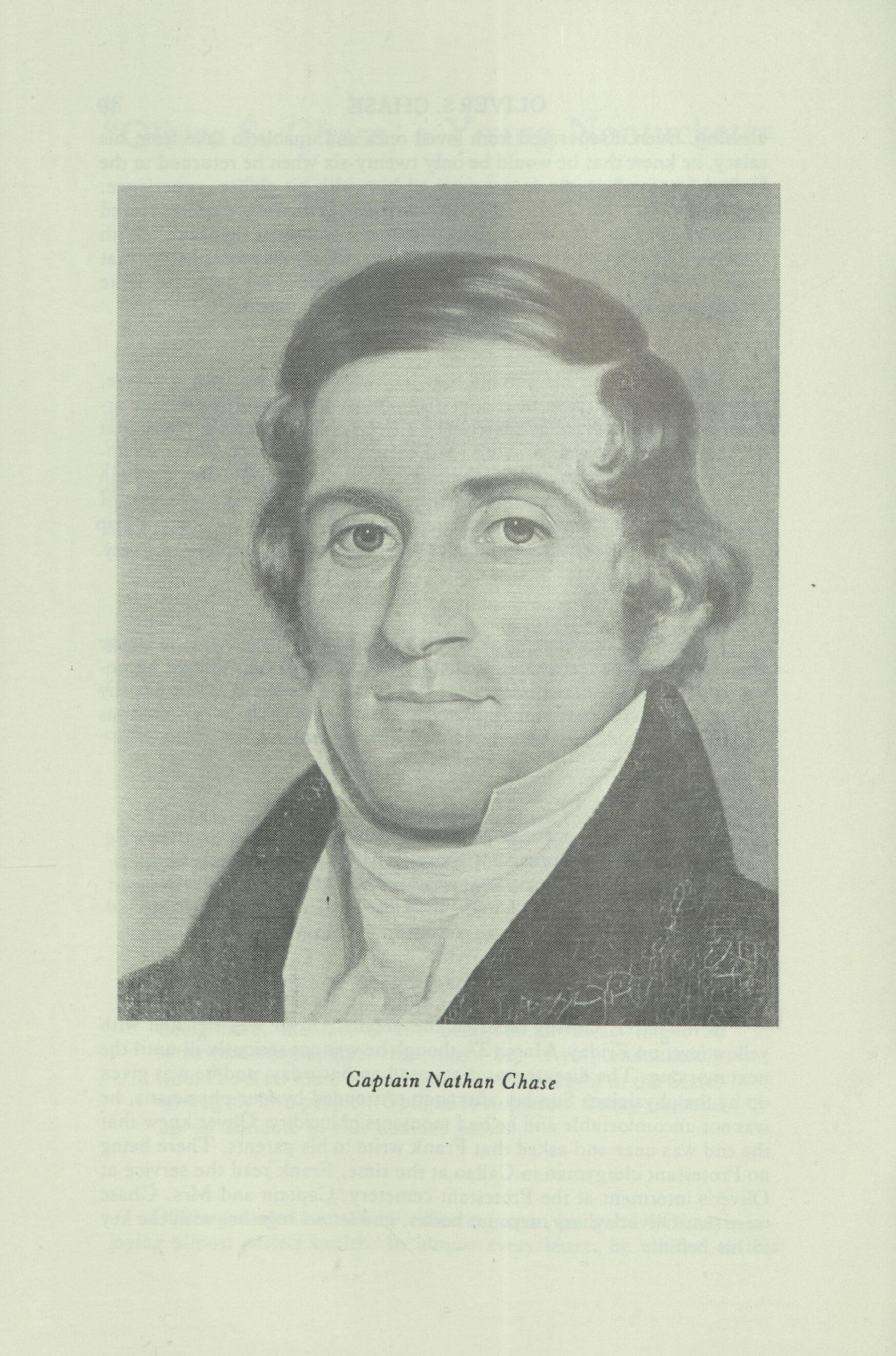

Oliver wrote to his parents that he had come down with a severe, though temporary, case of rheumatism (most probably rheumatoid arthritis), but he reported by his letter of a week later, March 18, 1868, that he had fully recovered. Having read earlier the details of Oliver's temporary paralysis, fever, and debilitated condition, Judith and Captain Nathan Chase must have smiled as they read some of Oliver's remarks: "I would not mind having an excursion myself," he wrote, "—say a trip down to Nantucket," A week later, Oliver reported a complete recovery.

It is next to impossible to conceive of the shock that Captain Chase must have experienced when sometime in mid-April he received an envelope with a thick black ink border and stamped with seal of "S. Crosby & Co., Ship Chandlers and Ship Agents." On the front were the ominous words: "Sad News". In the letter, Frank Crosby wrote:

I am very sorry to have such sad duty to perform as the writing of this letter, but there is no help for it, may God strengthen your heart in this your hour of trial and sorrow. Your son, Oliver S. Chase, died in the city on Monday the thirtieth of March at seven o'clock in the morning.

In the letter, Crosby reported the details. Oliver was stricken with yellow fever on Friday, March 27, though he was not seriously ill until the next morning. The disease was diagnosed on Saturday, and he was given up by the physicians Sunday afternoon. Attended by four physicians, he was not uncomfortable and he had moments of lucidity. Oliver knew that the end was near and asked that Frank write to his parents. There being no Protestant clergyman in Callao at the time, Frank read the service at Oliver's interment at the Protestant cemetery. Captain and Mrs. Chase were sent Oliver's diary, account books, and letters together with the key to his coffin.

C a p t a i n N a t h a n C h a s e

OLIVER S.CHASE 21

Frank Crosby attempted to write some comforting words: "It may be some consolation to you to know that your son led a very quiet, respectable life here and left a large number of friends to mourn his loss." To recount the kind words of Josiah Barrett, the Dodge sisters, Mrs. Dodge, and Oliver's kin would be superfluous. Oliver's letters themselves stand as a fitting memorial, for he had the gift of making others sympathize with him. Those who read his letters could not but relive the happiest moments of youth's fleeting hours and again life's transient sorrows.

Young Chase's letters showed both sides of his personality. His exuberance was evident in his sorrows as well as his joys. Had Oliver survived, he would have undoubtedly benefited from the balance and perspective which comes with maturity. It is especially regrettable that given his keen enjoyment of life and his unyielding devotion to duty, Oliver did not live to see happier days and to cheer those who might have come to know him.

Mr. Aubuchon has been the Archivist at the Peter Foulger Museum since June of 1977, having been engaged by the Association through the grant for this work obtained from the National Endowment For The Humanities, Division of Research Grants.