17 minute read

Great Point Lighthouse Threatened By Erosion of The Beach

13

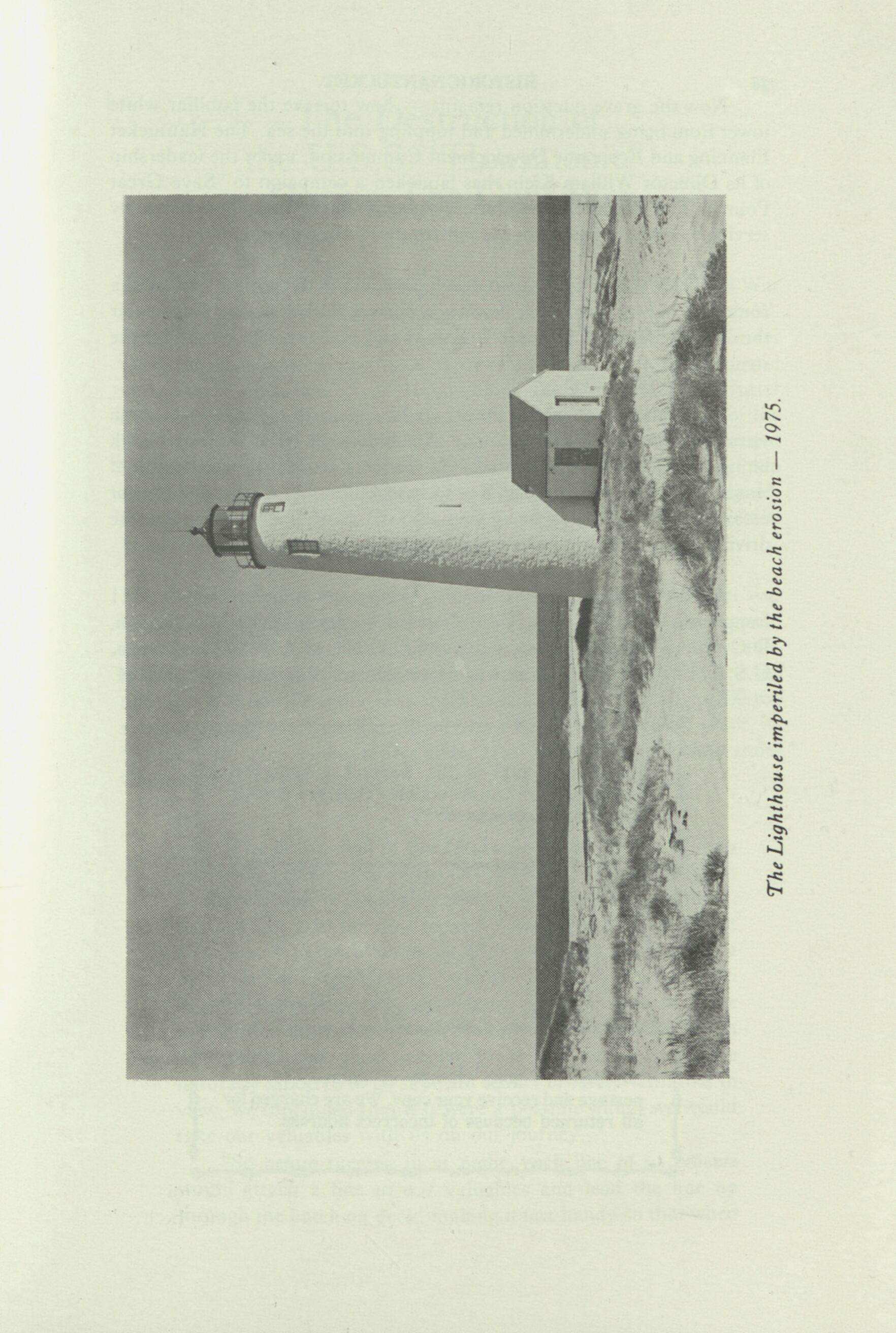

ACCORDING TO THE most recent advices, the erosion of the outer beach at Great Point has reached a point where, unless nature reverses the condition, the tall white lighthouse standing there is in great danger of toppling into the sea. Government and State engineers have been studying the situation and agree that there seems to be no hope of checking the wearing away of the barrier beach. The work of moving the tower has been considered but the cost, if accomplished, appears to be prohibitive. Funds for possible saving of the old structure are being collected by the Nantucket Historical Association and other organizations in the Town.

The present lighthouse at Great Point was erected in 1818, and was originally lighted by whale oil. But the history of the establishment of a lighthouse here actually began before the Revolutionary War, when the town of Nantucket, recognizing the need for a lighted beacon on Sandy Point (as it was originally known) appointed a committee composed of Frederick Folger, Christopher Starbuck and Reuben Coffin, to draw up a petition to the General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony for the establishment of such a light. Nothing was done by that body, and the advent of the War precluded any further action.

With the war's end, and the return of whaling activities to the Island, another petition was forwarded to the General Court. At this time, with economic conditions in the new country demanding, among other factors, strong support for the recovery of the whaling industry, the General Court approved and on February 5, 1784, a resolution provided for the erection of the Great Point Light at Nantucket as soon as possible. On November 11, 1784, Richard Devens, the commissary general, was granted 1,089 pounds, 15 shillings, and 5 pence in addition to 300 already paid out "for erecting a lighthouse and small house at Nantucket." The lighthouse was erected that next year—1785. On June 10, 1790, the "lighthouse, land, etc., on Sandy Point, county of Nantucket," was ceded to the Federal Government.

Overseeing the initial construction of the light was Captain Alexander Coffin, one of the Nantucketers who strongly advocated support of the Continental cause during the Revolution. John Coffin built the lighthouse lodge and an old account book records that "170 feet of

14 HISTORIC NANTUCKET

Pine board" was a part of the bill. Another interesting old statement shows that in 1797 some twenty panes of glass, measuring 13 by 10 inches each, were installed in the tower, which, with the freight bill attached, amounted in cost to 1 pound, 11 shillings, 6 pence—or $5.25.

The keeper selected for the new light was an excellent choice— Captain Paul Pinkham, a remarkably able mariner, who made a chart of the shoals in Nantucket Sound while serving as the Keeper of Great Point Lighthouse. Born in 1736, the son of Theophilus and Deborah (Paddack) Pinkham, he was a veteran of both the whaling and coastwise trades, and was a famous pilot of the waters in this area of southeastern Massachusetts.

Realizing the need for a proper chart he had drawn up his own, and it was published in Boston by John Norman in February, 1791. Not only did it show the dangerous shoals around Nantucket, but also those around the southern coast of Cape Cod and parts of Vineyard Sound. In one corner of the printed chart was an unusual testimonial signed by his colleagues on Nantucket, which also gave documentation to the use of the Great Point Light tower as a vantage point for the survey. The statement reads:

"To All Whom It May Concern: These are to certify that when the lighthouse was building on Nantucket in 1784 this survey of the Shoals was made from the Lantern (An opportunity never before had for so valuable a purpose.) by Captain Paul Pinkham & others by the help of the best Compasses and Instruments which could be procured, and it has been proved by Experience to be the most accurate Chart ever offered to the Public of those dangerous shoals (which are a terror to all Navigators) which has been run by with the greatest safety; and is fully approved. And that the Publication of this Chart, from its accuracy, cannot fail to be greatly beneficial to all Navigators who may fall in with said Shoals, is the judgement of us. — John Cartwright, Joseph Chase, Daniel Coffin, Nathaniel Barnard, James Barker, William Coffin, Silvanus Coleman, Alexander Coffin, Jr., Thomas Delano. Nantucket, September 1, 1790."

From a bill rendered June 10, 1794, only the best spermaceti strained oil was used in the light at Great Point. In a letter from Captain Pinkham to the Lighthouse Commission it cost 118 pounds, 15 shillings for oil that supplied the lighthouse from August 16, 1794, to May 1, 1795. Captain Alexander Gardner furnished the oil for 36 pounds per ton, or ap-

16 HISTORIC NANTUCKET

proximately 1,800 gallons. From May 8, 1793, to May 9, 1794, some 1,600 gallons were used.

The salary of the Keeper in 1799 was $166.66 per year, and was no doubt an increase from the first paid Captain Pinkham. On December 16, 1795, he had written Supt. Lincoln:

"Sir: It is my ardent Request that you will be pleased to lay before the Honorable Senate and House of Representatives the inclosed, and make use of the utmost of your Influence to carry it into effect, as the Smallness of the Sallary renders it very hard for me to Subsist. The twelve cords of wood which was allowed me by the Legislature of this Commonwealth as part of my Sallary now costs $96 landed at the Lighthouse, provisions in like proportion & all other Necessaries of life. Therefore you must know that the Small Sum of $250 without any other natural advantages is a scanty support for a Family thus far removed from all other immoliments whatsoever. Now Sir your ernest attention to this shall be rewarded and ever acknowledged by your humble Servent, Paul Pinkham."

Apparently, the salary increase was granted, although how many other benefits were allowed is not known. Half a century later O. C. Gardner as Keeper received only $250.00 per year as his salary (1849).

As an expected part of the Keeper's life he went to the aid of shipwrecks. In January, 1791, the schooner Codfish was wrecked on Great Point (a disaster not recorded in Gardner's remarkably complete list), and Captain Pinkham kept a careful record of the men and teams who worked over a four-day period to salvage the cargo. Apparently, the salvagers stayed at the lighthouse lodge, as their names are listed as either furnishing their own provisions, or "being found", by the Keeper's stores.

Another wreck involving the possibility of salvage occurred in November, 1793, when the sloop Farmer, Captain Abijah Hawley, became cast away" on Bishop & Clerks shoal off Hyannis on Cape Cod. Captain Hawley wrote Captain Pinkham on "Nantucket Point," informing him that as the wind was north and west he understood that some of the cargo had drifted across the Sound to the Point, and asked "if you find any of these articles I would thank you if you would procure them for me and keep them until you hear from me." The articles listed included a barrel of shoes (116 pairs), 1 bbl. of new rum, and a quantity of lumber.

GREAT POINT LIGHT THREATENED 17

What constituted the work-day routine at the lighthouse is revealed in a document drawn up by Captain Pinkham as an agreement between the Keeper and a possible candidate as his assistant. In it the assistant is to "attend and keep the lighthouse in good order, as well as other duties, such as fetching oil, wood, and hay and other necessaries, and is not to neglect his duty."

In consideration for such services the assistant was to receive $180 per year, "and to pay him from time to time as the said Paul Pinkham shall receive his Sallary." In addition, the assistant was to receive "onehalf of all Drifts and Prizes he shall obtain in the service and one-half of all Shark Oil and fish that he shall catch." Among other advantages he (the assistant) was allowed use of the east chamber, northeast bed chamber and one-half the kitchen and one-half the cellar and milk room." Not the least of the considerations was "one-half the profits of the two cows said Pinkham shall keep, he paying one-half the charges arising on said cows."

The career of Captain Pinkham as the first keeper of Great Point Light ended with his death on December 30, 1799. He was succeeded by George Swain, another Nantucketer. It is not unlikely that Captain Pinkham's passing was the result of helping to salvage the cargo of a schooner from Boston to Baltimore which came ashore at Great Point on December 3, 1799, on the inside of the point. After getting her cargo out, the schooner was finally hauled off the beach by favorable wind and tide aids, getting free on December 28. Two days later Captain Pinkham died.

The legacy of Paul Pinkham to both Nantucket and the country was his charts. Now one of the rarities in both collections and university libraries, they are excellent examples of not only knowledge but ability to present such examples of his experience in a form of value to navigators. One other memento of his life as the Keeper of Great Point Lighthouse is a notice which he wrote June 24, 1796, which contains probably the only contemporary account of the type of boat used by the lighthouse service at that time for rescue and utility operations. It reads as follows:

"Nantucket, June 24, 1796. Last night between ten o'clock and daylight next day was stolen from the lighthouse landing the lighthouse boat, in length eighteen xh feet, breadth about eight feet, with three sprit sails, a Road Anchor, and painted with a White Bottom, the top streak yellow and the next to that black; her inside paint Red; the mast yellow in the middle and Black at each end; a Black Stern and a White.

GREAT POINT LIGHT THREATENED

Strake around her stem — being the property of the United States. Whoever will Deteck the thief and return the property shall be handsomely Rewarded by Paul Pinkham, Keeper of the Lighthouse at Nantucket."

19

In 1812 the Keeper at Great Point was Jonathan Coffin. He had the misfortune to have the dwelling consumed by fire, and had to temporarily reside at a farm in Wauwinet or Coskata, making daily trips. His salary was raised to $196.67 to compensate for the long journeys to and from the station.

In November 1816, however, the lighthouse was entirely destroyed by fire. Some said the fire was purposely set, but no positive proof was ever forthcoming. On March 3, 1817, Congress appropriated $7,500 "For rebuilding the lighthouse at Nantucket, recently destroyed by fire" and $7,385.12 of this was expended in 1818 in erecting the handsome stone tower which still stands today.

A petition signed by many citizens and shipowners of Nantucket in 1828 called for the removal of Captain George Bunker, who was then keeper, because of his reportedly intemperate habits, but Stephen Pleasonton, of the Treasury, wisely refrained, after an investigation, from taking any action in the matter. The petition had suggested George Swain as a replacement for Bunker and such petitions, circulated by ambitious candidates for a keeper's job, or by disgruntled and disappointed applicants, were far too numerous to be acted upon without careful consideration of the source and the motive.

The Superintendent's decision to retain Keeper Bunker was not challenged. Ironically, Captain Bunker was killed on December 28, 1828, when the cart he was driving along the point was upset and he was caught under the load and crushed. He was 62 years of age at the time.

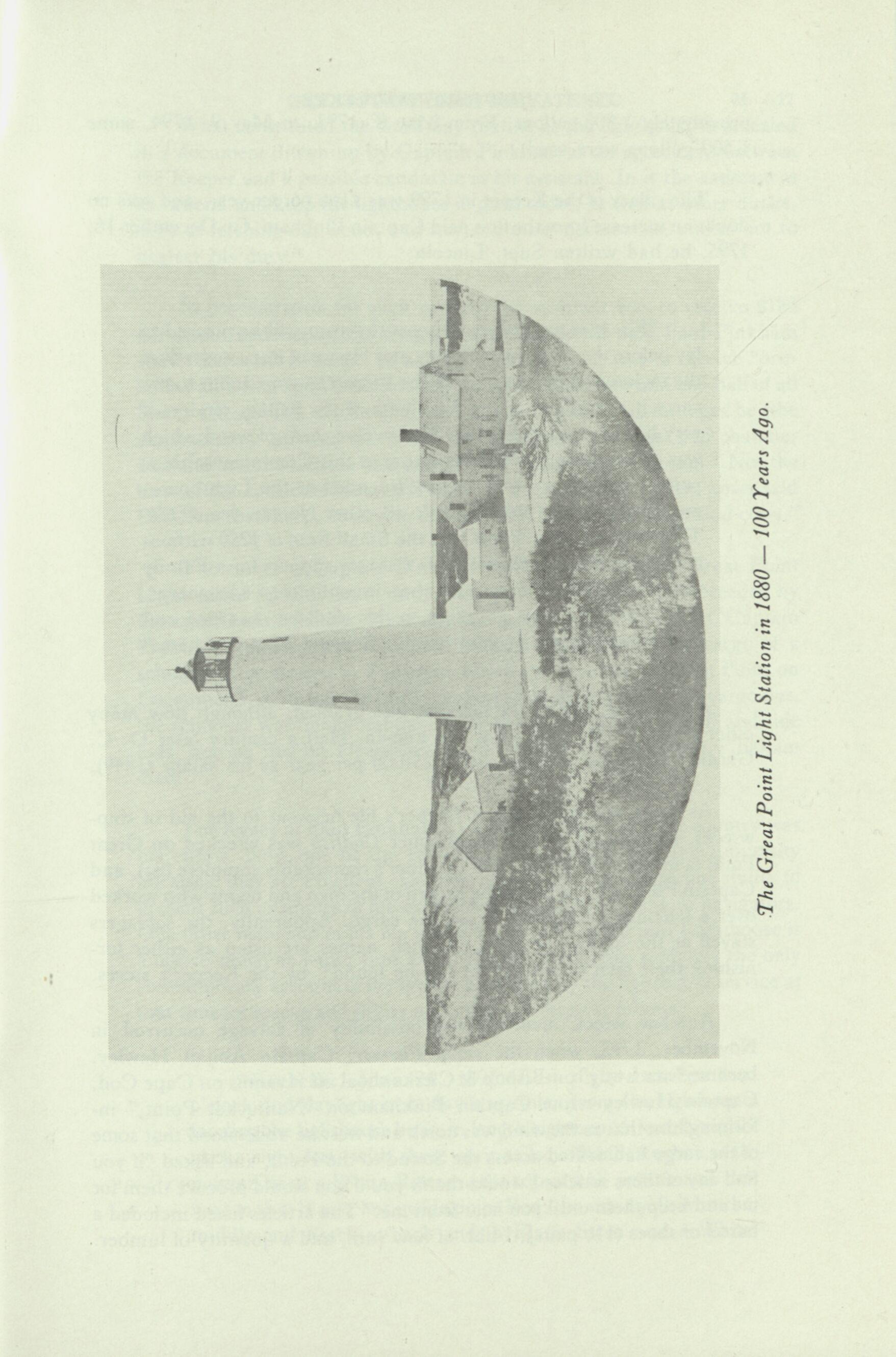

In his report of November 1, 1838, Lieutenant Edward W. Carpenter, USN, noted that the light was in a stone tower 60 feet high and 70 feet above sea level. It consisted of 14 lamps, 3 with 15, and 11 with 16inch reflectors, arranged in two circles parallel to each other and to the horizon. The lantern was 8% feet high and 9 feet in diameter. The tower and dwelling were connected by a short covered way "which, among these sand hills, where the snow must drift in Winter, is a security that the light will be well attended."

The importance of the Great Point Lighthouse was recognized more

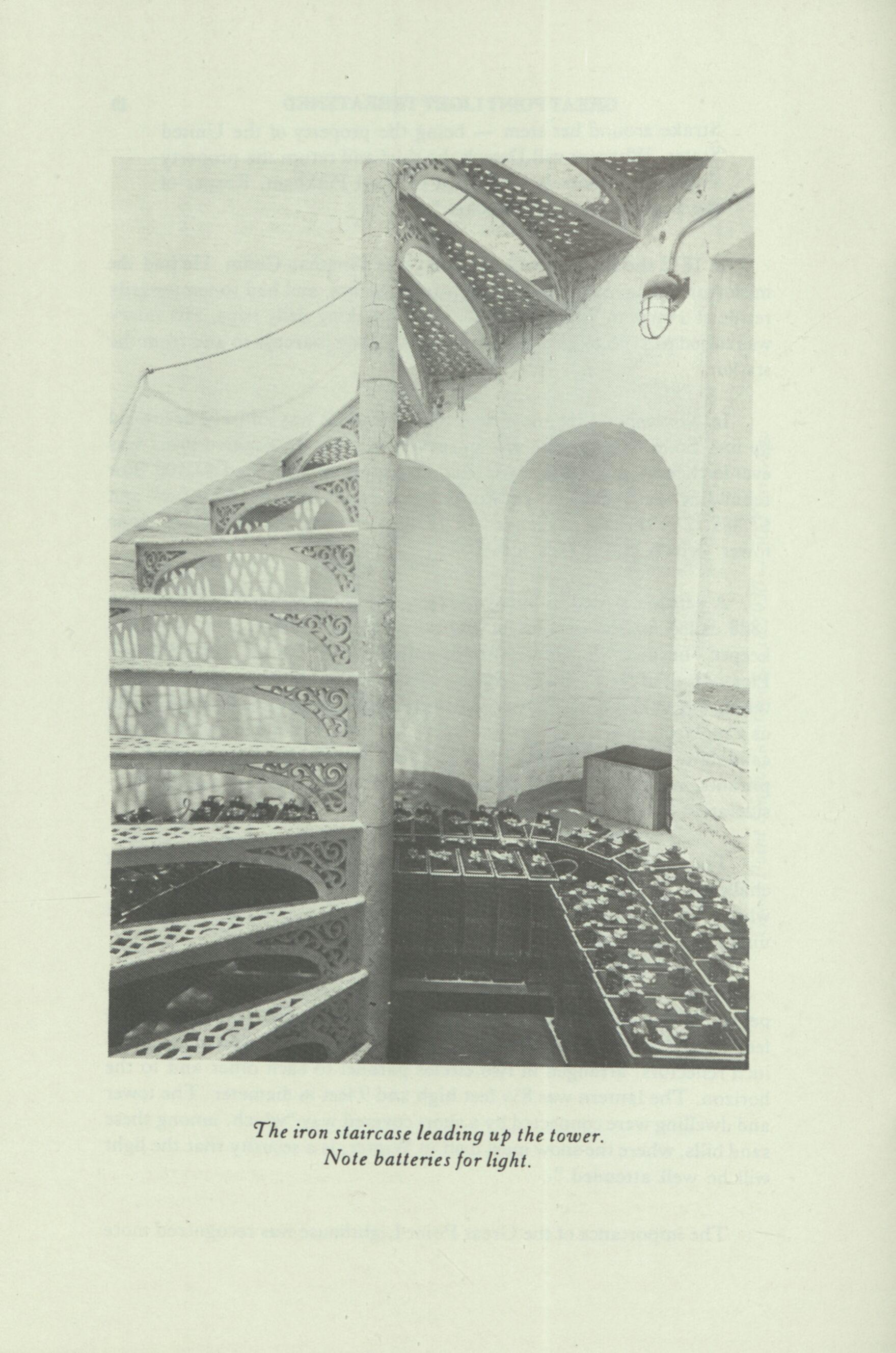

The iron staircase leading up the tower. Note batteries for light.

GREAT POINT LIGHT THREATENED 21

realistically in 1857, shortly atter the first brick tower was being constructed at Brant Point. In its issue of Saturday, June 20, 1857, the youngest of the two Nantucket newspapers, The Weekly Mirror, had the following description:

"Light-House Improvements. — We learn that Mr. Williams, who had charge of building the new Light-House on Brant Point last summer, is now on the Island, to see to still further improvements in the various lights and light-houses. The one on Brant Point is being painted and otherwise improved. A new walk is to be made between the Cliff beacons, and other improvements which the place seems to demand. Also, a new light-house tower is to be put up at Great Point, like the one on Brant Point. It will be built up within the walls of the present tower, in every respect like the one built last summer, except a larger lantern to accommodate a larger order of lights — the third order of Fresnel lights. We presume that in that place the lenses will be complete, as light will be needed in all directions; though the harbor light is only threefourths of a complete circular lens, because the remaining onefourth would be of no use to sea navigation. We say water navigation, because it may be of some use sometimes to those who in the "dry" season cannot see hardly how to navigate themselves."

During the extremely cold winter of 1857, one of the memorable events concerned with Great Point took place, The schooner Conanchet, of Plymouth, under Captain Burgess, bound for the New York market with 1250 quintals of fish, was trapped on the edge of Tuckernuck Shoal by ice, which formed a solid sheet all the way to the shores of Nantucket. As the vessel was close to foundering Captain Burgess and his crew attempted to crawl across the ice toward Great Point using planks. After nine hours on the ice, with the temperature at 12 above zero, the desperate men managed to reach the beach at the Point. Here they were given shelter in the keeper's home, and spent the night there, Mr. Swain bringing them to town the next morning. Here a subscription was raised for the unfortunate men and they eventually reached home safely.

In the following year (March 13, 1858) another fishing schooner, the I. & P. Chase, Captain Snow, with her hold filled with mackerel, went ashore in a snowstorm on the ocean side of Great Point. The crew landed safely and were taken care of in the lightkeeper's lodge. Her cargo was

22

HISTORIC NANTUCKET

later discharged and the schooner eventually floated off by Nantucket salvagers and towed into the harbor by the Island Home.

Again in October, 1860, Great Point was the scene of a disaster involving the schooner Nevis, Captain Bickmore, bound to Bangor, Maine, with a load of coal. Striking Great Point Rip at night, it was not until the morning that her precarious plight was discovered. Nantucket pilots Captain Alexander B. Dunham and Joseph Patterson, together with Davis Hall and two brothers of Captain Dunham, George W. and Frederick, went up to Coskata and then walked the beach to the Lighthouse. Despite the heavy surf and violent sea they launched the lifeboat about 11 a.m., and managed to reach the vessel and remove her crew, together with the captain's wife and child. All were cared for by the Keeper of the lighthouse at the lodge.

Between 1863 and 1890 there were 43 shipwrecks within the jurisdiction of Great Point Light. A number of vessels mistook Great Point Light for the Cross Rip Lightship.

On January 30, 1881, the keeper, Benjamin Pease, sighted the U. B. Fisk of Boston bound to Charleston, S. C., caught in an ice floe. The crew had abandoned ship but were unable to make shore. The keeper waded out into the water, up to his armpits, and threw them a small line. With this he sent them a heavier line which he used to pull their boat ashore, as their schooner was being crushed in the ice pack.

Several mariners, unfamiliar with Nantucket Sound, mistook the lightship and the lighthouse lights. Three schooners, including the William Jones, on a clear, moonlit night in April, 1864, became confused in determining the lighting pattern and all went aground in Great Point Rip. Fortunately, all got freed on the next high tide. During a heavy gale, on October 12, 1865, a schooner struck the bar and the captain managed to save his wife and three children by getting the longboat over the side and the crew managed to reach Great Point safely. The schooner went to pieces while they watched from the beach.

In 1866 the schooner Leesburg struck Great Point and the crew rescued. A month later, October 4, the brig Storm Castle mistook Great Point and Handkerchief lights. The cargo of lumber was jettisoned and the brig brought into the harbor, by Island salvors. The brig C. C. Van Horn, bound to Boston from Cuba, with a cargo of sugar and molasses, struck on Great Point Rip the day before Christmas 1866 and was a total loss, though the crew reached shore safely. The same thing happened to

24 HISTORIC NANTUCKET

another schooner in May 1867, and to one in December 1867. Still nothing was done about the confusion in the lights.

Wrecks continued. There were two in 1869, one in 1877, and two in 1878. In 1880 the West Wind hit the east end of Nantucket Bar, 4'/2 miles from the lighthouse with a cargo of ice. The vessel soon went to pieces, the crew being picked up later by a passing vessel and taken to New York.

Other wrecks occurred in 1887, 1889, and 1890. It was not until 1889 that the red sector in the Great Point Light was inserted to mark Cross Rip Shoal and the other shoals south of it. From then on the wrecks were less numerous although in 1915 the Marcus L. Urann was wrecked on the Wasque Shoal and Keeper Norton at Great Point helped rescue "13 men, a woman, and a cat." He was given a life-saving medal for this performance.

The coming of the automobile to Nantucket brought considerable change to old customs. The keeper, William L. Anderson, in 1933, in his auto equipped with balloon tires, transported 350 visitors to and from the lighthouse at Great Point. But the precedent in such transportation had been accomplished in 1922 by Harry Gordon, of Nantucket.

Today, Great Point Lighthouse is described as follows: "A white tower 71 feet above ground and 70 feet above water, visible 14 miles and located on the point at the north end of Nantucket Island at 41 degrees 23.4' N., 70 degrees 02.7' W. It is equipped with a 12,000-candlepower third-order electric light, fixed white, with a 3,500-candlepower red sector which covers Cross Rip and Tuckernuck Shoals."

There is no longer a keeper at the Great Point Lighthouse, this custom having been discontinued soon after the end of World War II, and an electric switch now turns the light on and off each night through a remote control device. Storage batteries provide the power.

During the night of February 16, 1968, a fire of suspicious origin destroyed the keeper's lodge, and the last vistage of family life at the Great Point station vanished. The old barn had been allowed to fall apart long before, and the oil house had similarly been abandoned. Only the white lighthouse remained, a familiar landmark to the fishermen and aviators, and at night its light could still be identified by mariners, in both the white and red sectors. In summer months many sports fishermen still use the beach at the Point, and many boats skirt the rip trolling. The modern auto has little problem in reaching the end of the Point.