12 minute read

By Edouard Stackpole

Lost in a Snow Storm An Island Sleighing Party in 1833.

by Edouard A. Stackpole (from the files of The Inquirer)

ON THE 2nd DAY of March, 1833, a heavy snowfall lay over the Island of Nantucket. The town, rising from the harbor up the gentle slopes of the Wesco Hills, had been transformed into a snow village, the houses huddled together as if in mutual admiration of the effect produced by the frost king. Stretching from Madaket to Squam, the Island had become covered by the white, crystalline blanket of winter, the wide commons unbroken stretches of purest white, dazzling in the morning sun, softening the undulating landscape.

With the sunrise the Town was suddenly alive. The blue sky and the soft air gave a touch of spring that belied the snow. A vagrant band of robins, obviously delighted, had cruised down harbor from their cold fastness of Coskata's cedars to circle backyard havens. Youngsters emerged as if by magic, dragging their sleds, their excited voices raised in eager anticipation of coasting at Dead Horse Valley or on Seul Winn's hills. Some young gentlemen appeared on the Square, striding down to the Union News Room, where they joined others, young and old, that thronged the room. Some exchanges brought laughter, and tobacco smoke grew thicker as the newcomers entered. A group of the younger citizens had occupied one end of the room, and the conversation became more animated. Suddenly, one of them raised his hand for a momentary silence. Others listened as he spoke. "Seth Swain's just had a great idea!" he announced. "How about joining him on a sleighing ride to 'Sconset." The response was enthusiastic. "Count me in," exclaimed one; "Sign me on," declared another; "When do we start!" called out a third. The announcer became suddenly serious. "It all depends on the girls," he remarked. "If we can get them to agree - put enough food together - we should get under way by ten o'clock!" The next few minutes found them counting sleighs. Within twenty minutes it was well arranged, and they parted to agree on a rendezvous on the corner of Union and Main Streets. Mid-forenoon found a gay cavalcade of fifteen sleighs speeding along the way, over the closely packed snow, with fifteen whips crackling in the air as the horses responded to the excited drivers. Snuggled under warm robes, some with hands clasped in the strong hands of their- escorts, the bevy of Island belles, laughing and whispering in turn, caught the enthusiasm of all. Along the old South Road they sped. The landscape was one vast, glittering blanket of white, as far as the eye could see. The gay atmosphere

LOST IN A SNOW STORM 7 became subdued with this aspect of nature's grandeur; then the happy spirit again prevailed. Beyond the Captain Worth farm, the horses were slowed, and they rested for a time. In the hollows, some sheep were pawing the snow to get at the tasty roots below, but, for the most part, not a vestige of life could be seen.

At the crest of the hills, with 'Sconset in view, they greeted their destination with shouts of anticipation. A musical chorus swept the air as they sped down Bean Hill and onto the stretch to Philip's Run. The girls' high voices rang out; the young gentlemen grinned; whips cracked; the sleigh runners swished; and the sleighs finally slowed as the deeper snow was met. Finally the panting horses reached Bunker Hill, and, as if by magic, a group of 'Sconset folk was out to greet them. A young villager looked at his friends with some astonishment, and then, bowing, welcomed them with a mock gravity. "What brings you young idiots out?" inquired a weather-beaten villager. The tallest of the sleigh-riders answered with an obvious respect, as he recognized a retired shipmaster. "We thought we'd make a visit - with some friends. If we can get some good fish chowder, we'll be off on the return voyage before the afternoon is well on." The shipmaster shook his head. "Wind's due to shift by then," he observed. "Better take a few lanterns." 'Sconset's chimneys were beginning to smoke. The village youth became their guide, and the sleighs continued on to Mrs. Cary's haven, where the horses found a warm barn and feed, while the party made themselves comfortable in the confines of Mistress Cary's several tiny rooms. In the largest of her quarters she laid a rough table, with long boards and trestles. While the young people chatted, 'Sconset friends suddenly appeared. While the laughter and quips flowed, along with the cider, Mrs. Cary and her helpers prepared a codfish chowder, the compelling flavor soon filling the room. But the tall leader was watching the small clock on the wall. Before they could beguile themselves with prospects of more to eat and more songs to sing, he was up rapping the boards for attention. "Get on your duds," he announced. "In ten minutes we have to get under way. It's already after three o'clock. Time's awasting!" Reluctant to leave, the party finally were again ensconsed in the sleighs, and once outside the shelter of the little houses, a cold northwest wind met them, worrying the snow and sending long streamers over the road. Due to the quiet, wind-less character of the storm of the previous night there had been no drifts. But the snow was now stirring, and the tracks of the sleigh runners were only faintly seen. A dull smudge hung above the western horizon. "Guess the old man was right," muttered the leader, "that looks like more snow." "Oh, well, we've got two hours of daylight at the least," replied one of

his companions. "The stars light us home, with these lanterns." Once up the slope of Bean Hill, with the horses given a breather, the prospect changed, however. The wind was now directly ahead, and the snow was sweeping across the old tracks in waves. Urged on, the horses seemed to sense the need for action and responded with a will. But the drifts had formed and the progress dramatically lessened. Where once was song and banter the gaiety was more subdued, although there was still an effort to sustain the former mood. The cold had now become stronger as the temperature dropped. The breath of the horses became like the snow itself, and the efforts more labored. As the wind increased, and the snow swirled higher, the drivers found they were unable to see and allowed the horses to instinctively keep to the road, now twisting as it headed toward Hinsdale.

In Nantucket-Town, anxious families watched the storm building. As the sun became hidden the concern deepened, and several conferences were held. Would the young people have started homeward in time to avoid the blizzard? Perhaps they would decide to stay in 'Sconset over night. It depended on the time of their departure. The streets of the Town were now filled with swirling, twisting clouds of snow. Now hidden, the sun could only be noted by the dwindling glow in the western sky as it neared the horizon. Now the wind increased to half a gale, whistling in the chimneys and tearing at the tree branches. The watch was summoned. Veteran mariners, who had the proper orders in handling a ship at sea, found themselves doubtful of what they might now say. Finally, they decided the townspeople should be alarmed. The bell in the South Tower began to ring. Hurriedly a number of volunteers were provided with sleighs and blankets, lanterns and candles. Hastily deciding on courses for action, these sleighing expeditions were dispatched, accompanied by special cargoes of tar barrels, to be lighted as beacons on the road past Newtown Gate. In contrast to the gaiety of that morning party there was little talk, merely low-voiced advices, and heads bowed to the growing gale. In the brief lulls, the sound of the bell tolling in the tower came to them. When the hidden sun finally lost its last bit of light as it dropped into the sea, the first beacons were lighted, the flames first leaping high and then becoming almost flattened by the snow-filled gusts. A few men, needing action, began shoveling at the drifts around the old sheep gate and cleared a wide area, only to see the snow drifts cover their work. At this moment, a different sounding in the bell strokes came to the waiting men. It was the quick, staccato rhythm that aroused them. Fire! Many raced away to the new scene of emergency. Flames had been seen shooting into the snow-filled air from a roof. "Where away!" came the voices. Shouts and horns led to the scene. The horror of the situation was all too apparent to these people. A fire

in the center of a town built of wooden structures, compactly arranged, wherein seven thousand souls dwelt. The flames could spread through the streets from house to house, hurled on by a northwest gale, the flaming torches tossing from street to street, consuming dwellings and menacing lives. Brave men cringed at the thought; wives stood with blanched faces; children huddled around the hearthstone caught by the evident terror in the faces of family and friends. But Providence was truly on the side of the Islanders that night. The house-top fire was more threatening than dangerous, as a bucket brigade had quickly assembled and the flames "scrounged out". A swift report was passed from street to street, eventually to the small band of men at the Newtown Gate. But the town was now thoroughly alarmed. No one went early to bed that night. Somewhere, out on the commons, there was a caravan of sleighs, with three-score of Island people, wandering about, trapped by their folly in the bitter snowfall.

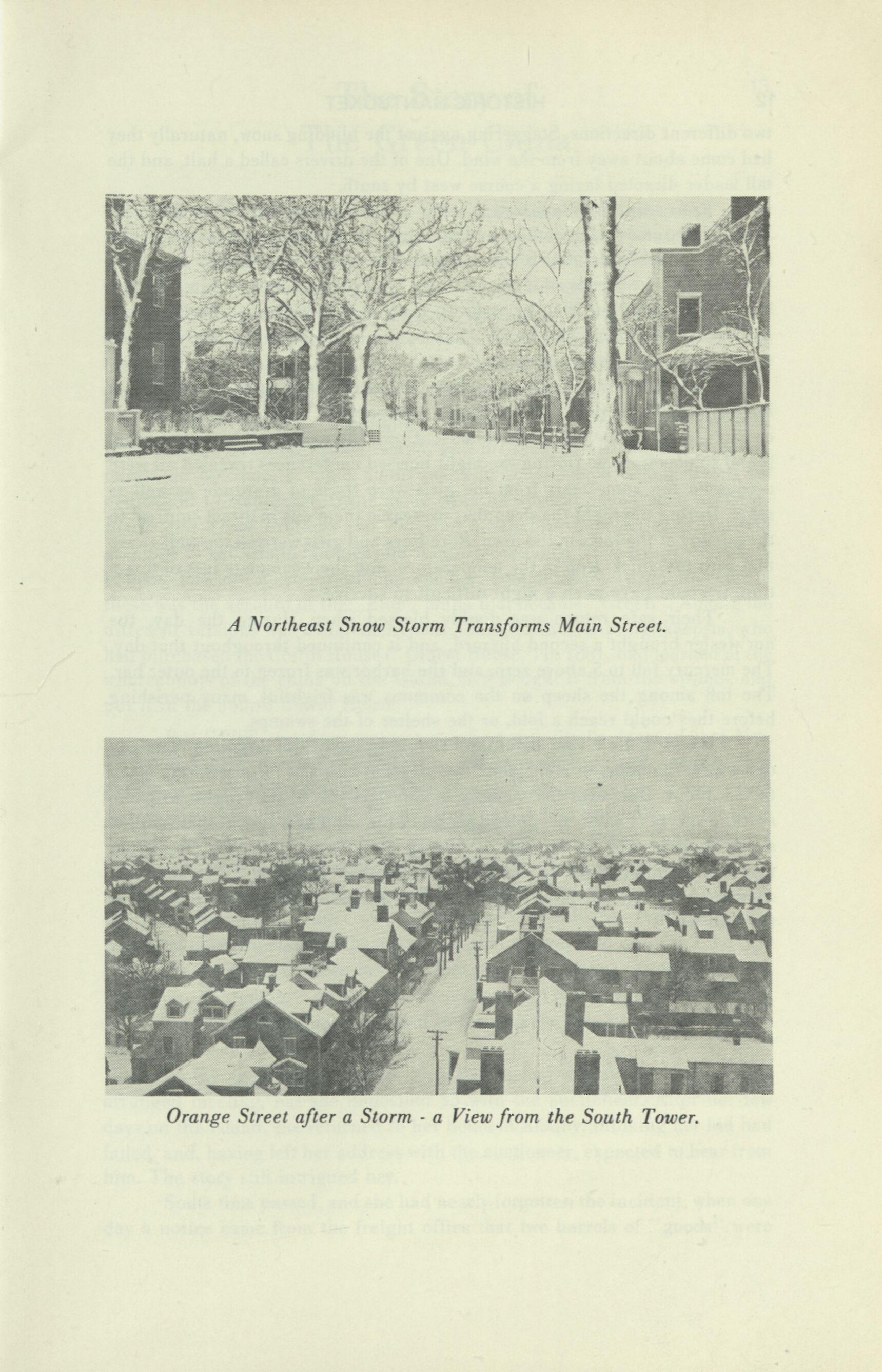

At sunrise, the watchers at the outskirts of the town had returned home and their places taken by search parties now slowly making their way out-oftown. The snow had diminished as the wind dropped away. The weary searchers who had been waving torches in the night were replaced by men in sleighs who found their progress slowed considerably. Nothing could be seen in a world of snow-covered landscape. And then the sound of horns were heard, coming from the town. Speeding couriers appeared at the Newtown Gate headquarters of the searchers. The watchman in the tower, with his spyglass scanning the scene, had spied a solitary sleigh winding through the drifts along the Old South Road. Extending his horn through an open window, he sounded long blasts, and people gathered at the tower for the news. One sleigh! What had happened to the others? What had transpired during that dreadful night! The answers were soon forthcoming. The watchman's glass soon picked up other moving figures on the road. One more sleigh had appeared; then another; then another. Word spread with amazing swiftness. Soon the sleighs made a closer appearance; to become the cavalcade again as they drove silently, albeit slowly, the length of Orange Street. As they reached the center of the way into town, a voice rang out breaking the tension in the gathering onlookers' faces. "Where in all creation have you been?" The answers to the many queries on that night's adventures were simple but adequate. When the drivers found they were lost in the snowstorm they had given the horses their heads, trusting the beasts would by instinct find their way to a farmhouse or a sheep-fold - or some place of shelter. But, this procedure served to temporarily separate the cavalcade - an almost fatal circumstance. The horses led the way for a few minutes, and then decided on

Orange Street after a Storm - a View from the South Tower.

12

HISTORIC NANTUCKET two different directions. Staggering against the blinding snow, naturally they had come about away from the wind. One of the drivers called a halt, and the tall leader directed laying a course west by south. Proceeding in this direction, after a half hour another halt was called. While they remained together, huddled against the savage onslaught of the snow, a sudden lull found them compelled to listen. It was then that they heard one of the horses whinney and then start up, and they let him take the lead. It was only then that they noticed three of the sleighs had disappeared. But the leading sleigh had found a haven, and a farmhouse suddenly loomed out of the snow-driven night. Lanterns were quickly swinging in the darkness. A voice hailed them; a farmer quickly hurried the half-frozen occupants of icy sleighs into the incredibly warm kitchen of the farmhouse. Down the road the other sleighs had found similar havens. During the night hurried conferences revealed all were accounted for; some tears from the girls were those of gratitude as well as relief. During the night the sleep that overcame them was in direct contrast to the anxiety of the folks in the town. Both boys and girls were all too well aware that with the quick drop in the temperature, and their complete loss of direction, it would have been a night difficult to survive. Their safe return was doubly blessed when, during the day, the nor'wester brought a second blizzard, and it continued throughout that day. The mercury fell to 5 above zero, and the harbor was frozen to the outer bar. The toll among the sheep on the commons was frightful, many perishing before they could reach a fold, or the shelter of the swamps. It was many a year before the sleighing party was forgotten. The gay departure; the hours of merriment; the pleasant hours at 'Sconset, were often talked about. But, with the memory of the darkness of that night, with the swirling sheets of snow, the doleful sound of the wind as it tore at their chilled sleigh shelters, and the miracle of finding their haven, they would recollect this part in quiet times. It was a tale to tell their children. To be lost in a snowstorm was one adventure; to be saved from the storm was quite another the best part!