5 minute read

by N. Parmenter and H. Spokes

by N. Parmenter and H. Spokes

THE WHALING SHIP Susan sailed from Nantucket Harbor in the summer of 1826 for what was hoped to be a profitable voyage hunting in Pacific waters. She would return three years and two months later, from her maiden voyage, carrying 2,582 barrels of sperm whale oil and 121 bbls. of whale oil, a fine initial harvest for her owners — actually the most successful of her seven whaling voyages.

Built in 1826 from the sturdy oak and ash of the northeastern forests in early America, she was one of many ships which were proliferating up and down the eastern seaboard at that time, built exclusively for the dirty, dangerous job of whaling throughout the oceans of the world.

The trade would flourish until the 20th century, providing oil to light the lamps of a growing nation's homes, farms and factories. In turn, the profits would provide seed money for increased shipbuilding, tobacco and cotton production as well as funding for the expansion of railroads. The effects of the whaling industry had far reaching consequences for the growth of a young country.

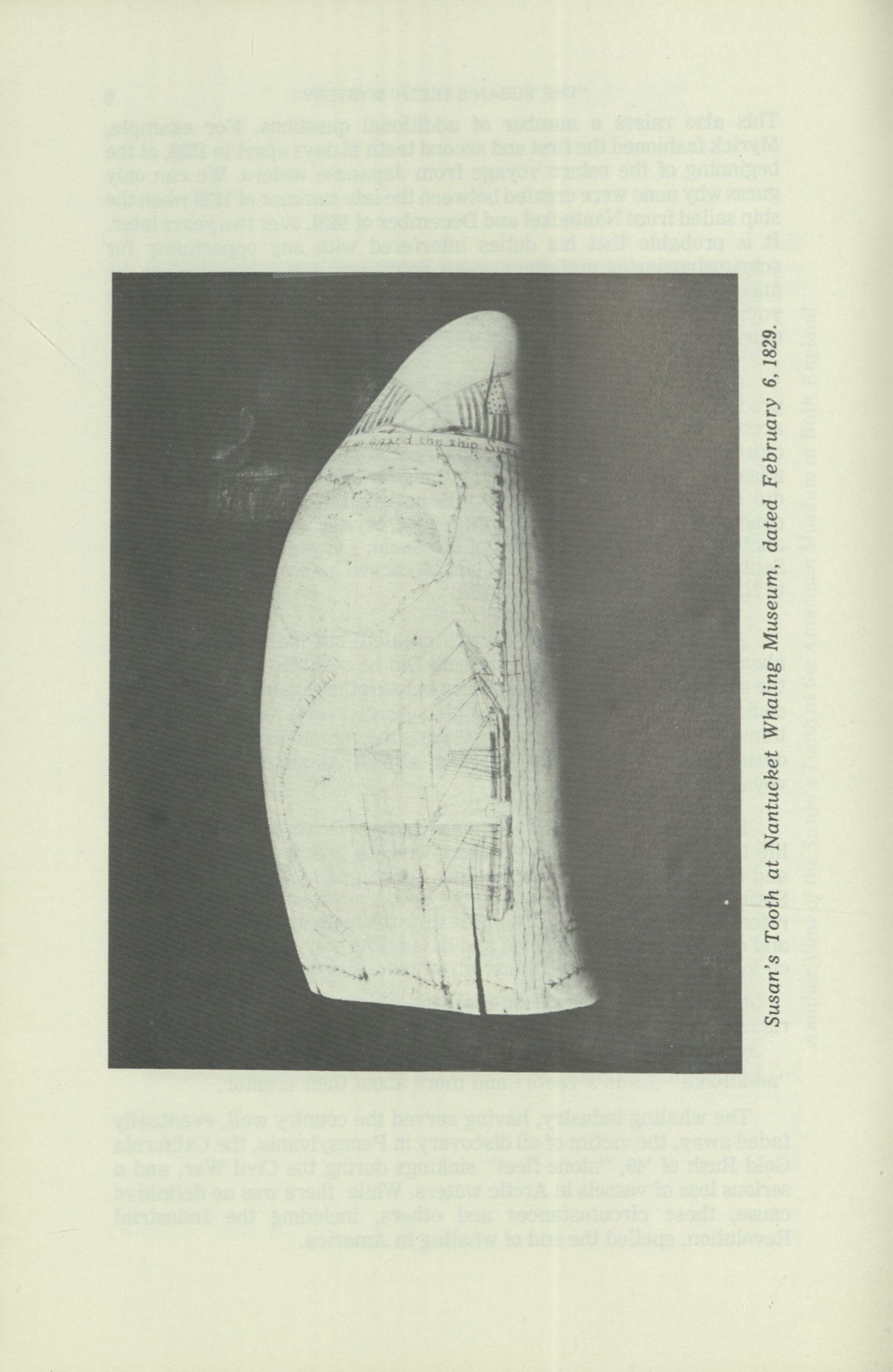

Among historians, researchers and collectors of the whaling era, however, this voyage also marked the beginning of a mystery which inflames the romance we attach to that time; for on board that day, August 21, when the Susan made ready for the open sea, was Frederick Myrick, destined to years of hard work, indescribable boredom and some notoriety. We know very little about this man or why he should be caught up in "the greasy work of whaling". Nonetheless, his life is worthy of note, because it was Frederick Myrick who fashioned something of a diary of that voyage, scrimshandered into a number of the ivory teeth from the Susan's various skills. They were appropriately named the "Susan's Teeth."

In signing and dating them in a manner uncommon to the time, he unwittingly created a place in history for himself as a progenitor of the art of scrimshandering. His work and others have added immeasurably to an understanding of our early history, and substantially to the value of collections throughout the world. For example, one piece of Myrick's work sold recently at Sothebys for $29,000.

Myrick fashioned at least seven such pieces, according to the only previous accounting contained in the Monograph "Susan's Teeth and much about Scrimshaw", Everett Crosby (1955). The author and others have commonly referred to these as the only known specimens extant. Our own research substantiates 14 Susan's Teeth, and we believe there could be more left to surface (see Chronological Summary).

The eventual number becomes interesting when we consider that, of our verified dates, all were created between December 10,1828 and September 4, 1829, establishing them as products of a single voyage.

"THE 'SUSAN'S TEETH' MYSTERY'

9

This also raises a number of additional questions. For example, Myrick fashioned the first and second teeth 18 days apart in 1828, at the beginning of the return voyage from Japanese waters. We can only guess why none were created between the late summer of 1826 when the ship sailed from Nantucket and December of 1828, over two years later. It is probable that his duties interfered with any opportunity for schrimshandering until the Susan's holds were filled. Nonetheless, he apparently found considerable time for his Susans during the return voyage, completing some teeth in less than three days, and usually requiring no more than two weeks or so between finished products.

On March 4th of 1829, however, he signed a tooth and apparently produced no more until August 22, 1829, a period of over 5 months, according to the known dates. Again, we can only conjure at what required his energies during that time: peril to the ship, illness on board, a leave on a distant shore, or something far less romantic. If indeed he did create more work during this period, the examples are unaccounted for in our research. In any event, Myrick soon followed up with another tooth nearing the end of the Susan's voyage; his tooth, dated September 4, could well be the last he carved before the ship returned to Nantucket on October 27,1829.

Are there other pieces Myrick created, but did not sign or date aboard the Susan or another vessel? Did he quit this art? Did he quit the sea, or did something befall him before other examples of his work could be completed? Concerning his Susan's Teeth, we are inclined to think not, for in the Susan series, there is a commonality of purpose and design which bonds them together almost as sisters of that first voyage.

Each, for example, bore the inscription "Death to the living, long life to the killers, Success to sailors wives & greasy luck to whalers" and each made mention of the ship Susan and of Captain Frederick Swain, her master for three of the seven voyages she made. Many referred to the ship's location at the time the tooth was scrimshandered and each was uniquely signed and dated. The only exception is a tooth on loan to Mystic Seaport Museum which is not dated.

Beyond these artistic similarities, there still remain questions relating to the mysteries of the teeth and how many more exist.

We plan to continue our on-going study of locations and dates of "additional" Susan's Teeth - and more about their creator.

The whaling industry, having served the country well, eventually faded away, the victim of oil discovery in Pennsylvania, the California Gold Rush of '49, "stone fleet" sinkings during the Civil War, and a serious loss of vessels in Arctic waters. While there was no definitive cause, these circumstances and others, including the Industrial Revolution, spelled the end of whaling in America.