19 minute read

The Search for Hero

22

by Diana Brown

Now I have arrived at this extensive city called London, but what am I to do here in this great and strange city. I am a stranger, I know no one, I have no ship, I have no clothes fit to wear. I have no money to help myself. I have no friends here or acquaintances. What course now must be steered or taken next for the best for I must have board and lodgings and clothes to make me decent, but who in London, although a great extensive town, is to supply me for nothing...[?]

These thoughts were written after an unfortunate voyage my Nantucket great, great grandfather made between 1802 and 1804.

William Wilkes Morris was born in Nantucket in 1780, his forebears having come to the island around 1720.1 know little about his early life except that in 1801, he married Priscilla Chase, the daughter of Isaac and Eunice (Brown), in the First Congregational Church.

After my mother died in 1975, I acquired a Salem Hepplewhite desk where she had kept some papers relating to her Nantucket ancestors. Among them was a journal I had never read but which contained, I had been told, an account of the great Nantucket fire and a description of a whaling voyage my mother's ancestor had taken in the last century. As a child I remember only looking at the pretty drawings it contained of Nantucket family coats of arms. (My mother had heard it said that, in later years, Morris drove a calash with his own coat of arms on its side.)

I was to find that the journal covered his life between 1802 and 1846, the year before he died. There are also sporadic notes, the financial accounts of his navigation school, arts and trade secrets (such as how to prevent flies from sitting on pictures), the dimensions of Royal Navy and merchant ships and many maxims of Benjamin Franklin, his hero and the namesake of his last son, my great grandfather.

Not until 1986 did I undertake the task of transcribing his notes which were somewhat difficult to decipher. I did not change the

23

Historic Nantucket

style or vocabulary, but put in punctuation and used the original spelling to show more clearly his mode of speech.

My husband and I soon realized that the story of William Morris' voyage on the Hero from 1802 to 1804 was an exciting adventure, in a period of history that we knew little about. I was determined to find out more about the man and his ship as well as the personalities and events he described.

Morris sailed from Nantucket to New York in August 1802 to join the ship Hero, captained by Stephen Rawson of Nantucket. A little more than a month later, the ship arrived in Havre de Grace (Le Havre) where it remained until February. It was outfitted as a whaler and sailed under the French flag on a voyage to the South Atlantic.

After moderate success on the African coast, the Hero travelled westward to Santa Catarina Island on the coast of Brazil where the ship took on fresh supplies and water. Unaware that the English had abrogated the Treaty of Amiens, Captain Rawson allowed the ship to be boarded by a small party from a Letter of Marque(l) called Swallow. Its captain, David Smyth, seized the Hero as an English prize. In quick succession, however, the Portuguese seized Swallow because Charles Frederick Smyth, the ship's supercargo(2) and David Smyth's uncle, had been jailed for smuggling goods ashore against local law. Hero's papers, of such interest to our research, were still on board the Swallow at this time.

Captain Rawson was obliged to leave the Hero at Santa Catarina and proceed to Rio de Janeiro where he was to answer charges laid by the Portuguese in the Smyth case. Rawson persuaded his chief mate, William Morris, aged twenty-four, to take the vessel to London, pointing out that the experience would be beneficial to him.

At St. Helena, the Hero fell into the company of four East India Company ships with which it returned in convoy to England. On arrival at the Thames estuary, the officers from the flagship of the English fleet ransacked the Hero and impressed some of the crew for service with the Royal Navy.

When the ship arrived at the Thames dock, my great, great grandfather was unceremoniously discharged from the ship, and he was left without any means of support. His story so far leaves many questions unanswered:

The Search for Hero 24

what was the origin of the Hero? what happened to it in London after its capture? what information on Hero is available in other sources, such as the logs and journals of numerous ships it "spoke to? what is known of William Morris, the man and his family? what is the story of the Swallow?

Our first efforts to answer these questions took my husband and me in the spring of 1987 to Nantucket where we devoted much of our time at the Nantucket Historical Association Research Center to finding birth, marriage and death records of the Morris family. Through these records we ascertained that the first Morrises arrived from Holland in the early part of the eighteenth century although their origin was English. We found the will of John Morris, the first family member to settle in Nantucket and a man of considerable property when he died at a very old age. There were few references to William Morris, but we learned more about his forebears and descendants through various records at the Town Building and microfilms of period newspapers at the Atheneum.

After William's ill-fated voyage, we uncovered little about his personal life, and it is not clear if he continued to go to sea. No reference has turned up so far to his service in the crew of another ship.

We know he had one daughter, Eliza, by his first wife, Priscilla. She was born in April 1808; therefore, he must have returned to Nantucket sometime prior to that. He also had a son William, born in 1812, who lived for only one-and-a-half years.

For economic reasons William and his family went to Ohio in 1814 along with other Nantucketers. This was a dark period in Nantucket history due to restrictions imposed by the Americans and the English on shipping and trade in general. Priscilla died in Ohio in 1817, and a year or so later, William returned to Nantucket where, in 1819 or 1820, he opened a navigation school that continued for about twenty years.

Lucinda Wood became William's second wife in 1820. They had six children, my great grandfather being their last issue. Following a common practice, they named their first, a daughter, Priscilla Chase

25

Historic Nantucket

after the wife who died in Ohio. We were able to find some specifics about his children and later descendants, as well as a few "skeletons in the closet."

Two of William's offspring died as children to the family's great grief. Priscilla died a young mother, and his son William, a crew member of the ship Spartan, drowned at the bar at Tombez (now Tumbes, in northwest Peru). Lucinda outlived her husband by almost thirty years and died a very old lady in 1876. On her grave at Prospect Hill Cemetery is the epitaph "Perfect through Suffering."

Later in 1987, we began to look into the ship Hero, and ships mentioned or "spoken to" on the voyage. Through various New York merchant newspapers in the Library of Congress, we discovered that Hero was advertised "for Havre de Grace, the very fast sailing copper-bottomed ship, burthen 240 tons.... For freight of 500 barrels on board of passage - having excellent accommodations: apply to John Juhel." To our knowledge there was only one Hero that corresponded in tonnage to ours, and that ship was built in Hingham, Massachusetts in 1792.

At this time Thierry du Pasquier, author of Les Baleiniers francais au XlXeme siecle, introduced himself to me with a very interesting letter. He had heard through a mutual French friend that I had a copy of a journal concerning the Hero. This ship was one of the captured vessels he was researching for another book; consequently, he was interested in reading my great, great grandfather's report. He told me that, according to French records, our Hero was built in Calcutta in 1797. After converting the French tonnage and dimensions to American ones, we had to admit that this ship resembled the Hingham Hero very closely. We were puzzled, and so was M. du Pasquier.

Our first really exciting discovery came in the Mystic Seaport museum library where I was again searching for references to any of the ships mentioned. I came to realize in this process that one had to explore all conceivable avenues. In looking for Swallow, for example, the subject headings "Letter of Marque" and "Privateer" yielded nothing. Not to be put off, I searched further under "Smyth" (the captain) and found Swallow, Letter of Marque, slaver, and a short description of a journal written by William Mann, Swallow's carpenter. It referred to the capture of French whalers in Brazil during the period 1803-1805.

I obtained a copy of this journal from the American Antiquarian

The Search for Hero 26

Society. It corroborated much of what my great, great grandfather had written concerning Hero's capture by Swallow, and told us, furthermore, what had happened to others, such as Captain Rawson, after the Hero's departure to England. When the Swallow finally left Brazil, even though it was fitted as a whaler, it functioned primarily as a slave transport from Africa to South Carolina. The unscrupulous Captain Smyth eventually dismissed William Mann from the ship, and he and his journal found their way to America.

We next decided to visit England and France. My daughter had done some preliminary research for us in London in 1987. Through a process of elimination, at the British Museum and the Public Records Office, she discarded various leads that were of no use. She also obtained for us the registration of Swallow and some other ships spoken to as well as charts and maps of the period we were studying.

We had met, at the 1988 Kendall Whaling Museum Symposium, Mr. Charles Payton, an English expert on whaling, who had offered his assistance to us. At the end of March 1989, we met him again in London. He gave us invaluable advice on how to find our way around the London Archives and about which references to concentrate on. No one, however, held much hope that we would find out anything more than we already had.

On April 3, 1989, we were in the Public Records Office at Chancery Lane, London. It was raining outside and generally miserable. We were, nevertheless, clothed, warm, well-fed and had a little money in our pockets - a far cry from the situation in which William Morris had found himself almost 185 years earlier. My husband located an index reference to Le Heros du Havre, Rawson, master. We applied for the material, and soon a large box was in front of us. We began a search of our treasure in this box of ships' condemnation papers (3).

The ships all began with the letter H, and the papers were in chronological order. The documents were tied with string and filthy with black, soot-like dust. It was evident they had not been opened for a very long time. We sorted through ships' names such as Hirondelle, Hoop, Hebe - and finally, Le Heros du Havre, Rawson, appeared! We began to read the evidence given to the court by both the captors and the captured. There was, first, the testimony of David Smyth, Swallow's captain, who had returned with the Hero, then that of four crew members from both ships.

27

Historic Nantucket

On June 1, 1804, William Wilkes Morris testified. It was a curious sensation to see his familiar signature on each page of the transcript. The court questioned successively a Swedish mariner from the Swallow who had joined Hero in Brazil as a member of the prize crew; a fourteen-year-old French boy who had been Hero's cabin boy since Le Havre; and finally a crew member from New York who had been with the Hero since leaving there in September 1802.

The court asked these crewmen the same thirty or more questions: what did they know about the ship, its origin, the crew, the owners, purpose of the voyage, contents of cargo, the capture, the whereabouts of the ship's papers, and any unusual circumstances relating to the voyage?

From the mariners' evidence, the most pertinent new information we extracted for our research was that Le Heros du Havre was formerly called the Little John of Liverpool and had been built in Bengal. (This confirmed du Pasquier's contention.) The French had captured the ship and sold it in Cayenne to the American firm of John Juhel and Co. which brought it to New York where it was known as the Hero of New York.

On this basis, Nicholas Delonguemare, a partner in Juhel and Co., made an appeal to the High Court of the Admiralty, claiming the ship was American. Both the ship and its contents were appraised and all the cargo itemized. Oil began to seep from the casks into the hold of the ship, and in July 1804, Delonguemare asked the Court to expedite the sale of the contents.

Later that year, one of the joint owners of the Swallow protested at the delay in settlement of this case due to the fact that David Smyth had disappeared, leaving no attorney to conduct his affairs. This owner, Peter Young, stated on good authority that he believed that Smyth would never return to England.

The Court then concluded Le Heros du Havre should be sold, and the proceeds divided among the owners after all debts incurred in the handling of the ship had been paid. The ship was finally sold in August 1805 but, much to our chagrin, the record makes no reference to the identity of the purchaser. It would have been possible to obtain this information from the customhouse, but we discovered that a big fire in 1814 had destroyed all their records.

Because the condemnation hearing's evidence reconfirmed the ship's tonnage of approximately 240 tons, we searched the Public Record Office in Kew for a registration of either Hero or Little John

The Search for Hero 28

of that size. We went through all the registration books from 1797 to 1808 but found nothing that confirmed this evidence.

London does not, however, have all the registrations from other English ports, and I contacted the archivist at the National Museums and Galleries on Merseyside, Liverpool, where all original Liverpool ship registrations are kept. I was informed that there was no record of a Little John, and moreover, nothing on any other ship of similar tonnage. We asked about ships built in Bengal at that time and received the same negative reply. In short, we still had not succeeded in uncovering the origin or the identity of our Hero.

Having been unable to find a reference to a Little John of similar tonnage in any shipping register, we decided in the spring of 1990 to search New York newspapers from the period 1800-1802 in the hope of finding Hero's arrival in New York from Cayenne. At the American Antiquarian Society (Worcester, MA), the New York Gazette of November 13, 1801, revealed Hero was quarantined in New York, having arrived from Cayenne on November 10, captained by Hammond. It was accompanied by Abigail, and both ships belonged to JohnJuhel & Co. The shipping news revealed also that it was an English "guineaman"(4) named John of Liverpool, and that it had been a prize ship!

At this point we turned our attention to the logs of the East India Company ships which had accompanied the Hero from St. Helena to the English Channel. We discovered three of the captains' logs at the India office of the British Library which gave us further information about the convoy to London and included occasional references to the Hero.

We located the manning list of Swallow and her registration as a Letter of Marque at the Public Record Office in Kew and Chancery Lane. At the National Maritime Museum Library in Greenwich, we learned in Lloyd's List that Swallow was captured in 1805 (presumably by the French) and brought to Martinique, while en route from Africa to the West Indies. In late fall 1989, my daughter subsequently discovered at Greenwich that Swallow was originally a Royal Navy ship, launched at Blackwall, London, in 1795. While in naval service, it was active in the South Atlantic. Between 1797 and 1799, it captured five French privateers. Swallow was sold and made a Letter of Marque in May 1803. My daughter also found reference to an aquatint of the sister ship Pelican, launched at the

29 Historic Nantucket

same yard that year with the exact dimensions of Swallow.

Paris was our next stop where we first contacted M. Thierry du Pasquier to discuss our research to date. He gave us an introduction to M. Henrat, the head of the Maritime Department at the National Archives, who was helpful in pointing out possible sources.

We were not, however, very successful in finding new information here although we located some references to Le Heros du Havre in colonial papers of Cayenne which protested the Portuguese authorities' lack of protection in Brazil for French ships. There was also a letter about John Juhel who had some trade interests with the town.

It is worth mentioning that, until this point, we were unaware of how research in this time period is complicated by the French Revolutionary calendar which divided the year into twelve months of thirty days each. (The remaining five or six days were called "complimentary.") Since the first New Year's Day under the new system fell on September 22, 1792, we had to make complicated conversions to date any piece of information!

On our return to Washington, we spent several days at the National Archives. Now that we knew more about our ship, we were looking for a New York certificate of registration of Hero. There was no registration as such, but we did find some miscellaneous papers which showed a certificate of ownership from the port authorities in New York. They were in a category misleadingly headed "sealetters"(5). The first, dated 1801, spoke about M. Juhel's purchase of Hero in Cayenne. It contained, however, no information about the origin of the ship, its previous history or name. The second paper, dated 1802, included the official survey report of the pertinent dimensions of the ship. Oddly enough, our Hero had almost exactly the same dimensions as the Hingham Hero, differing only by inches. Some other references to Hero were not to be found in the box where they should have been. The staff could give no explanation.

We continue our search, undaunted by this and other disappointments. We are aware, for example, of the faint possibility that ship's papers may still exist for the Hero in Brazil, in Portugal or Cayenne, and for Swallow in Brazil, Portugal or Martinique, where it was taken after its capture in 1805. Last year, I wrote to various museums and archives in Brazil, but little material is available. There are letters from the Governor of Santa Catarina to the Viceroy in

Search for Hero

30

Rio de Janeiro which are still in that city, according to an article which mentions Swallow. The task of tackling these manuscripts is still before us.

We have come to realize that there is no substitute for doing one's own research into the original material. Furthermore, one should never be deterred by the comments of well-meaning experts who might express an opinion that nothing more is likely to be found. We have disproved this time and time again.

In conclusion, I should like to mention some of the other people who have given us special assistance and encouragement: Mr. Edouard A. Stackpole and Mr. Wynn Lee of the Nantucket Historical Association, and Jacqueline K. Haring and the staff of the NHA Research Center; Mr. A.G.E. Jones of Kent, England; Mr. Paul Morris of Nantucket; Mr. Norman Brower of the South Seaport Museum, NY; Mr. John Vandereet, curator of Maritime Archives at the National Archives, Washington; Mrs. Barbara Simmons, curator of manuscripts at the American Antiquarian Society; Mr. John McDonough, manuscript historian of the Library of Congress; Miss Virginia Wood, maritime manuscripts, Library of Congress; and Anne-Marie Bruleaux, director of the archives of Cayenne (French Guiana).

Any information or advice from readers will be welcome. Please address: Mrs. Colin Brown, c/o The Research Center, Nantucket Historical Association, P.O. Box 1016, Nantucket, MA 02554.

NOTES (1) A Letter of Marque is a license or commission granted by a government to a private person to Fit out an armed vessel to cruise as a privateer and make prize of the enemy's ships and merchandise. The term is also used to describe the vessel. (2) The supercargo is an officer in a merchant ship in charge of the commercial concerns of the voyage. (3) In a manner similar to persons charged with crimes, the High Court of the Admiralty decided the fate of ships. The process is called condemnation, but as we found out, it has nothing to do with the seaworthiness of the ship. (4) Aguineaman is a ship trading with Guinea and, hence, a slave ship. (5) Sea letters were a form of ship's passport, and were often written in four languages. Signed by the President of the United

31

Historic Nantucket

States, they were issued to every whaling master when he left port. They contained the official stamp and signature of the collector of customs, and signatures of the deputy collector, a notary public and the master. They gave the master the right of free passage once he had taken an oath before an appropriate officer that his vessel was of United States origin, and they requested officials of foreign ports to receive him, the vessel and cargo, and "treat him in a becoming manner," permitting him to transact appropriate business (The Voice of the Whaleman, Stuart G. Sherman).

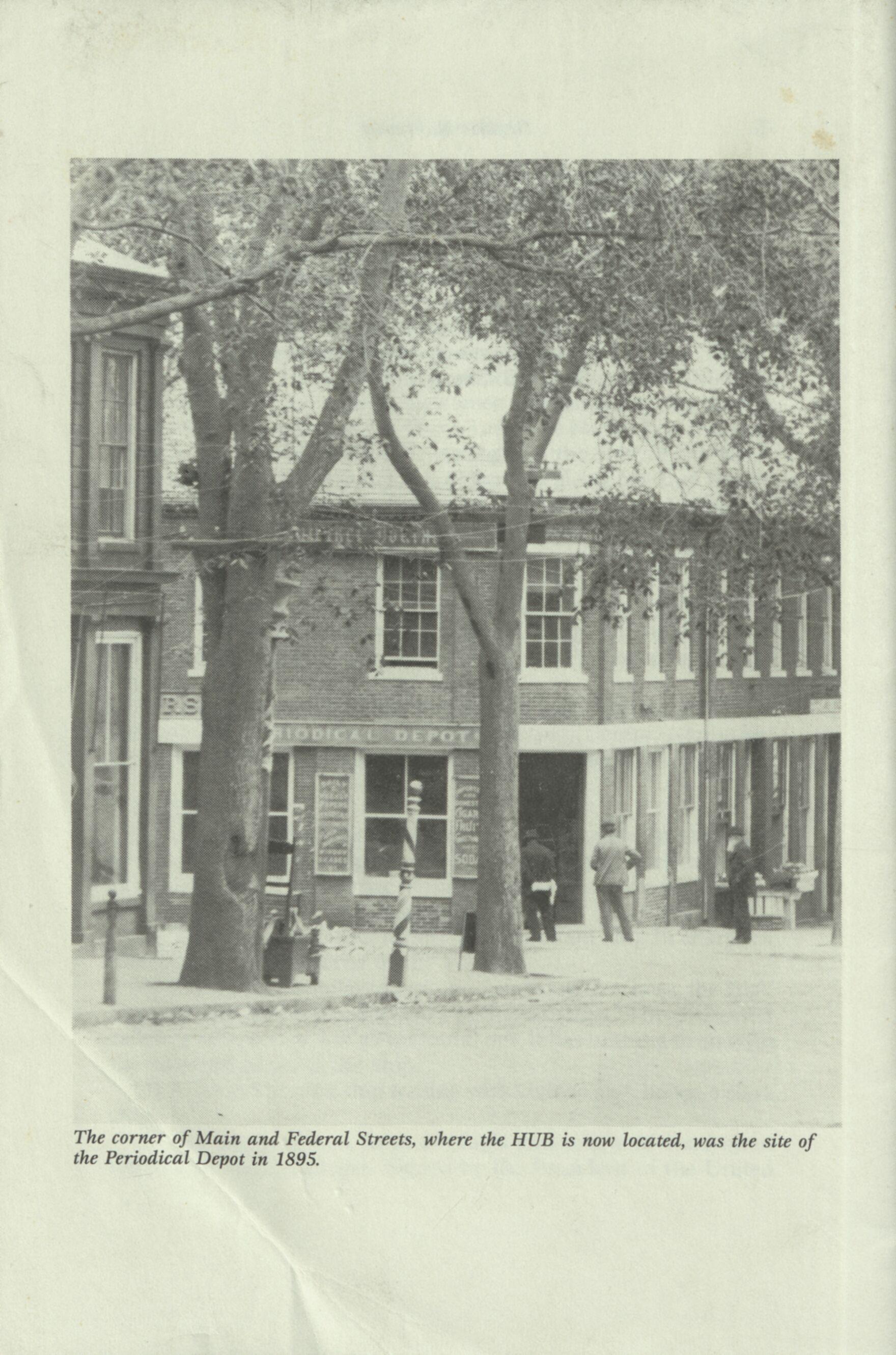

The corner of Main and Federal Streets, where the HUB is now located, was the site of the Periodical Depot in 1895.