Landscape with a band-aid

Written research conducted from June 2024- oktober 2024

Social Justice Lab

Design Academy Eindhoven, Netherlands

Written research conducted from June 2024- oktober 2024

Social Justice Lab

Design Academy Eindhoven, Netherlands

This publication is a continuation of my thesis research, delving deeper into the question of what it means to become-with. It builds upon and extends the ideas I have explored during my Master’s thesis, with the hope of contributing new perspectives to Veenhuizen—a village steeped in history and layered with complex narratives. The foundation for this research lies in the unique context of Veenhuizen, a place governed by Gemeente Noordenveld and rooted in its transformation from a Benevolence Colony to a prison town, recently recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site. This project is part of the broader Design Deal, a decade-long collaboration between the Design Academy Eindhoven (DAE) and various stakeholders in the region. Guided by DAE, this initiative seeks to confront regional challenges through embedded design methodologies, addressing issues such as sustainable energy, economic revitalization, and cultural preservation.

In this publication, I weave together historical narratives, artistic research, and contemporary challenges, aiming at fostering a dialogue that encourages people to formulate questions that consider the needs of the more-than-human world, expanding the scope of how we understand and interact with our environments.

By engaging with its stories, landscapes, and communities, I seek to promote more inclusive and interconnected ways of thinking that recognize the entanglement of human and non-human actors in shaping our world. This research is grounded in the concept of the landscape as an interface, which reimagines landscapes as dynamic platforms for engagement with cultural heritage. Instead of serving as static backdrops, landscapes become vital mediums where the past, present, and future intersect, fostering connections between people, communities, and their shared heritage.

This project would not have been possible without the guidance, support, and contributions of many individuals and organizations. First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor, Naomi Bueno de Mesquita, and coordinator, Toni Wagner, for their invaluable support throughout the research journey. Their feedback and encouragement helped shape this project into what it has become.

To the curator of the Prison Museum Willem Stohr, for your insights and for helping me articulate the core message of my research. Your contributions were instrumental in refining my vision.

To heritage policy worker at Gemeente Noordenveld Pauline Bezemer, tank you for generously sharing your knowledge and insights about Veenhuizen. Your expertise enriched my understanding of the village’s history and context.

To Bas Morsink and de Nieuwe Rentmeester team, thank you for providing a space where we could immerse ourselves in the life of Veenhuizen. Your hospitality allowed us to become with the environment, moving beyond the role of visitors to engage more deeply with the place.

Finally, I would like to acknowledge the collaboration and support of the many partners who made this project possible: National Prison Museum, Province of Drenthe, Municipality of Noordenveld, De Nieuwe Rentmeester, Drents Archief, Ketter&Co, and PI Veenhuizen. Your commitment to the Design Deal and its vision for Veenhuizen provided the framework within which this work could flourish.

To all those who have been part of this journey, your generosity, wisdom, and openness have been a constant source of inspiration. Thank you.

“The Colonies – A Story of People” is the title of the introduction in The Colonies of Benevolence, an Exceptional Experiment 1. The human story is evident, but what about the story of the landscape? How has it transformed over time, and what role do non-human entities play in this narrative? These are the questions I set out to explore by visiting Veenhuizen and delving into historical data about its evolving landscape.

Veenhuizen’s identity is closely tied to the story of the Colonies of Benevolence, a significant yet relatively short chapter in its long history. I wanted to uncover what defines Veenhuizen beyond this period: What existed before? How has the landscape changed over hundreds of years? And what are its current characteristics, shaped by both visible and imperceptible forces? My research began with the non-human components of the landscape— peat, water, and trees—and how they have both shaped and been shaped by human intervention over time. Peat stood out as a transformative element, both physically and historically. This led me to the title A Landscape with a Band-Aid, which reflects the layered scars of Veenhuizen’s landscape. The “band-aid” refers not only to the human impact on the natural environment but also to the visible contrasts in the landscape created by centuries of change.

This study examines the landscape through the lens of trauma and material flows, applying these concepts to both infrastructure and natural elements like peat. By exploring how the landscape was shaped—first by natural movements and later by human interventions—I aimed to understand how past transformations influence the present. For instance, contemporary land fragmentation(e.g., diverse ownership) highlights the complexity of current development and conservation efforts.

The research alternates between theoretical analysis and visits to Veenhuizen, summarized into a route that archives subjective, contemporary experiences of the area. This route and its reflections are presented in the chapter on Embodied Experience. Together, they offer a holistic view of

Veenhuizen, moving beyond the narrative of solely the Colonies of Benevolence to reveal the layers of time embedded in the landscape. Ultimately, this work seeks to foster a dialogue about how we understand and interact with our environments, encouraging asking questions that address the needs of the more-than-human world. It invites readers to see Veenhuizen not just as a place shaped by human history, but as a landscape shaped by ongoing material flows and ecological processes.

During my process I have formulated questions that have been guiding in my inquiry:

• In what ways were the needs of the subject (within a specific timeframe) unmet, and how did this experience hinder its further development?

• How does the landscape of Veenhuizen act as a repository of memory, both material and social, and how can embodied engagement with this landscape reveal layers of historical and ecological time?

• In what ways have past landscape interventions redirected material flows in Veenhuizen?

• How do contemporary restoration or conservation efforts interact with these historical transformations, revealing the scars and ongoing changes in the landscape?

In this publication I have some terminology which I am using in a specific way:

• ‘Veenhuizen area’ and or ‘Veenhuizen’: with this I refer to the whole area of Veenhuizen which is defined by the boarders of the municipality Noordenveld.

• Place: within this area I have defined little places. These places differ in experience form each other and are contrasting with each other. Sometimes the places are defined by experiences that have happened in that specific location in a specific period.

• Landscape: a body consisting out of material flows and natural characteristics which define the area of Veenhuizen.

When I first encountered Veenhuizen, something felt deeply off, even though the countryside appeared peaceful at first glance. I was overwhelmed by a sense of unease that I couldn’t shake off. More detailed, I would describe this feeling as pain, sorrow and loss. One of the first things that caught my attention was the stark, unnatural arrangement of the trees—the straight line of pine trees behind a line of oaks, and the sharp contrast of the pine forest across the canal.

I grew up in a raw landscape, where agriculture was practiced but on a small scale. Where the vegetable gardens were inaccessible every spring because the river had burst its banks. And where the border of a forest had a winding rather than a straight line. Perhaps that is why my discomfort, and my attention went to the trees and the straight lines in this landscape. I felt sorry for something that was once there that I could not see anymore. The vast landscape that was there was gone, transformed into a grid. In this situation, I was experiencing something I could not quite pin down, to where it comes from. I wondered what was lost in the transformation of Veenhuizen and if the landscape of Veenhuizen is in pain? I was curious in finding an understanding of what it means when a landscape is traumatized and if the pain is engraved in a place, has it become a trauma?

The word “trauma” originates from the Greek language, meaning wound or injury—something that arises from an impactful event.2 Wounds, whether physical or psychological, can be visible or hidden. While most wounds heal naturally with time and, occasionally, additional care, trauma often lingers. A definition of trauma that resonates deeply with me comes from Dr. Gabor Maté. He describes it as a psychological wound—a profound imprint on the mind, body, and functioning—resulting from unmet needs that inhibit growth and development. Trauma, he explains, is an invisible force that shapes our lives in ways we may not always see. Dr. Maté highlights that every being is born with essential needs, and when these are not fulfilled, the natural process of development is interrupted, leaving a lasting mark.3

In this case I see the landscape as a body, a being. Building on Dr. Gabor Maté’s definition, the following question can be formulated: In what ways were the needs of the landscape unmet, and how did this experience hinder its further development?

Inquiring the needs of the landscape means understanding how it would and could develop. I investigated the core characteristics of the area and how it developed over the years. My approach to understanding what the landscape “needs” begins with examining its primary materials—water, sand, clay, and peat—tracing their roles from the earliest stages of its development. I derived this view form Thomas Nail his Theory of the Earth in which he sees the earth not merely as backdrop but rather as a stream of materials which are influencing each other.4 Understanding the materials and how they move gives me an idea on how the landscape develops, silently showing what it needs.

By tracing the geological and ecological transformations that has shaped the landscape of Veenhuizen over millions of years, the predominant materials and their flow can be identified. As I already mentioned the main geological components of the Veenhuizen area include sand, river plains, and extensive peat formations. The formation and transformation of these materials have played a crucial role in shaping the place we see today. However, a big part of this area has transformed because of the materials and in conjunction with the interventions humans performed on it. This is what makes this area so special and shows multiple periods of time in one area.

Water is the driving force behind live and material flow. So, the first traces you see are those of water. How water moves through the landscape from high to low creating river beddings. The sand keeps the water in place and creates small ponds of life where peat can begin to grow. Peat can be understood in two distinct ways: as a geological soil formation and as a living plant ecosystem. The lower layers of a peat bog are formed from plant material that has accumulated in an oxygen-poor environment, preventing complete decomposition. This results in the formation of peat, which has historically been used as fuel.5

The upper layers of a peat bog consist (Sphagnum mosses), which thrive in the ter-saturated conditions of the bog. These absorbing and retaining water, ensuring the during dry periods. Additionally, they release decay of organic matter, further contributing forming the characteristic dome-shaped velop extremely slowly, because they have this point solely supplied by rainwater. Therefore, ecosystem that takes thousands of years to role in biodiversity, water regulation, and

consist of living peat mosses the unique acidic and wamosses act like sponges, the bog remains wet even release acids that slow the contributing to peat accumulation, peat bog landscape. 6Degrown higher and are at Therefore, a raised bog, an to form, playing a crucial carbon storage.

In the area of Veenhuizen the climatic conditions and the movement of water through the area allowed for peat to grow steadily over thousands of years, forming a raised bog landscape once called Smildervenen.7

For a long period, the peat bog landscape remained untouched and had the ability to grow and develop further. At one point people started to interact with it more extensively. This is the moment when peat became a resource, not only in the history of Veenhuizen but in the whole Netherlands. This dates back centuries, primarily occurring in the lower regions of the country. The peat moss peat, which made up the raised bog, was also discovered early on as a fuel. The commercial excavation of large areas of raised bog began in the 13th century; in the 15th century, technology was developed that also allowed the extraction of the (drowned raised) bog below the water table. From the beginning of the 17th century, peat extraction also began in the extensive raised bogs on the higher sandy soils of the northern and eastern Netherlands.8 These places are referred to as the peat colonies.

The first traces of these activities in this area are retrievable to digging of the canals. On the map of Drenthe, you can see something what looks like a road or a canal right into the heart of the Smildervenen. This is also the period where you can see the biggest change on the palaeographic maps.

The second biggest change is formed with the arrival of the Colonies of Benevolence in Veenhuizen, year 18229. During this period, the outer sides of Smildervenen was cultivated, leading to the division of the landscape and the creation of Fochteloërveen, one of the remaining bog landscapes in the region today.

The water wants to flow from Assen to Friesland and the water from Fochteloërveen wants to go in the direction of the Slokkert. This means that the location of Veenhuizen is in the middle of a stream valley where all the water accumulates. The wet conditions 1830 around the third asylum cause a higher infant mortality than in the first asylum.10 The failure to properly address water management in Venhuizen is one of the causes of the demise of the colonies. Until in 1886 the ruling of the area changes and the water management

is seriously tackled in order to make Veenhuizen as productive environment as possible.

To me, this shows that the area also has a power to tell what it wants, only if we are willing to listen to it. In the first maps I showed how the water flow fuels the growth of peat. Even though the drainage did not work properly more dams and locks were installed to keep water in control.

Since 1822, Veenhuizen has been through canal digging, forest cultivation, While much of the landscape has chteloërveen, has been preserved a glimpse of ‘Old Veenhuizen’ and have largely been converted into pastures ers maximizing productivity. However, has significantly impacted nature, plots to reduce pressure on Fochteloërveen.

been made as productive as possible cultivation, and land reclamation. been transformed, one area, Foby Natuurmonumenten, offering and its origins. Former peatlands pastures on sandy soil, with farmHowever, the use of artificial manure nature, prompting farmers to exchange Fochteloërveen.11 Additional efforts

are being made to preserve the area by maintaining its wetland conditions and ensuring the continued vitality of its raised bogs.12

The transformation of the Veenhuizen landscape reflects a complex interplay of natural processes and human interventions. Once dominated by vast peatbogs, centuries of drainage and extraction have left only fragmented remnants of this ecosystem, reshaping the area into a landscape that now functions under human control. Understanding the material flows that shaped Veenhuizen reveals the deep history embedded in its soil and the ongoing challenges

of preserving its fragile remains. As efforts to restore and conserve peatbogs gain urgency—not only for biodiversity but also for climate resilience—Veenhuizen stands as both a witness and a participant in ecological and social trauma, carrying the weight of human history and the loss of natural qualities within its segmented terrain.

In the previous chapter, I explored how landscapes are shaped by material movements. However, beyond the physical transformations of the land, political structures play a crucial role in determining its ownership, use, and significance. These structures shape authority, control, and access to land, influencing how humans interact with their environment. As a result, landscapes are not only shaped by natural forces but also by governance, policies, and societal ideologies.

In the context of landscapes, political structures define land ownership and access, shaping the way societies manage and engage with their surroundings. Policies on property rights, resource management, and conservation are all politically driven, determining whether land is preserved, exploited, or transformed. This dynamic has been particularly evident in the case of Veenhuizen, a brook valley landscape that historically supported extensive peat bogs. Peat, recognized early on as a valuable resource, played a fundamental role in the region’s development and resilience. However, the relationship between humans and peat has largely been one of exploitation, with peat treated primarily as an economic commodity rather than as a living, evolving entity.

Over time, the political governance of Veenhuizen has undergone significant changes, reflecting broader shifts in societal and economic priorities. While peat once covered vast stretches of land, today, much of it is gone, leaving only specific areas like Fochteloërveen as remnants of what once existed. This transformation is not merely ecological but also political— decisions about land ownership, governance, and resource allocation have determined which areas remain protected and which are repurposed or forgotten.

The history of land ownership in Veenhuizen illustrates how political decisions shape landscapes. Initially, the land was owned by small-scale proprietors, but this changed dramatically when Johannes van den Bosch acquired a large portion of the area to establish the Colonies of Benevolence. This marked a shift in governance, transforming Veenhuizen into a site of social

experimentation and controlled land management. Later, in 1859, when the colonies became part of the Rijkswerkinrichting, water management gained greater attention, further altering the landscape’s structure.

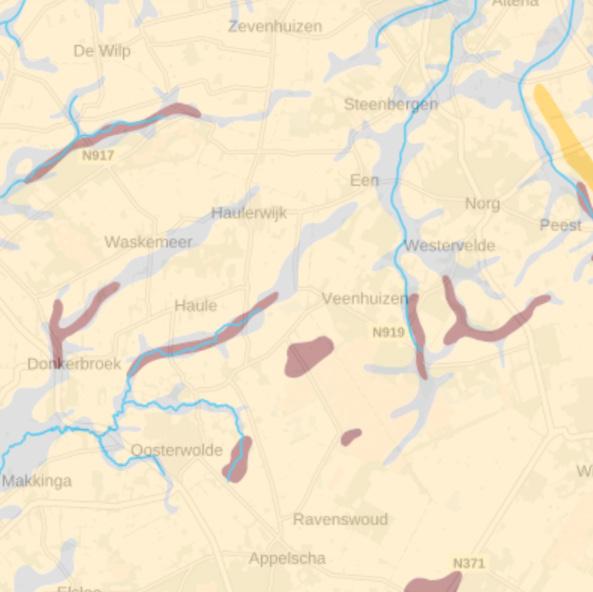

By 1938, another major shift occurred when Natuurmonumenten, a Dutch conservation organization, purchased what is now recognized as Fochteloërveen.13 This marked the beginning of a fragmented governance system, where different institutions and entities held control over separate pieces of land. As a result, the once-expansive peat landscape of Veenhuizen was reduced to a patchwork of regulated and managed areas, each governed by distinct policies and priorities, this is illustrated by the images on this page.

The political history of Veenhuizen highlights how landscapes are not only shaped by natural processes but also by human governance. Political structures dictate how land is used, who controls it, and which areas are preserved or exploited. The case of Veenhuizen and its diminishing peat landscape underscores the power of political, economic, and social forces in shaping our environment. Today, the fragmented ownership of the region serves as a testament to these forces, reminding us that landscapes are more than just physical spaces—they are also shaped by the decisions, priorities, and ideologies of those who govern them.

As discussed in the previous chapter, landscapes carry traumas—deeply ingrained systems that reflect past interactions and decisions. The way we manage and govern land determines whether these traumas are perpetuated or healed. By understanding the political structures that shape our landscapes, we gain deeper insight into how we engage with the environment and how we might reimagine our relationship with it in the future.

My first impression of Veenhuizen was that it is an austere landscape. Everything is bland simple. It causes your thoughts to go back and forth, to wander and settle down for a moment. On the one hand, visiting Veenhuizen gives you a peaceful feeling and on the other hand, the landscape possesses something artificial, and peculiar. And in some places, it evokes intense feelings.

At the start of my research, I tried to gather as little background information as possible about the place and focussed on whatever caught my attention. Later in my process, I added archival material and background information, I have shared with you in the previous chapters. Showing the different periods through which Veenhuizen has developed as a farmers, colony and prison, village. This information gave me an extra layer on the various states Veenhuizen has gone through.

During my visits, I kept track of where I visited and how I did so by bus, car, bike, or walking. I collected photos of the things that caught my attention. These may be normal things that normally don’t raise questions however they did for me. I thematically clustered these results so that it represented the feeling I experienced at that place. In this process I reflected on my feelings combined with the information and historical material about the place.

This helped me in describing the layers in a place and being able to provide better meaning in the distinction between what I experience right now, what happened in that place years ago and based on that how the experience could have been different in the past. As I described earlier, I experienced a heavy feeling. This is how I came up with the concept to describe the landscape as traumatic. I was curious How I can better interpret my feelings in this place. Does my feeling depend on the place. How am I influenced by what I know about the place? What does belong to me? What is captured by this place and what belongs to the landscape?

I believe that unprocessed stories linger. By attuning ourselves more closely to our surroundings, we can perceive and feel beyond our own assumptions. A place is shaped by people, while a landscape is a dynamic interplay of materials—each influencing and setting the other in motion through interactions with humans and animals. I also believe that a place holds a natural energy, a presence that carries its own story. This area holds many hidden narratives, layered within its terrain. My quest is to distinguish what belongs to the landscape itself and what is tied to the place’s human history. With this in mind, I stepped into the area.

Entering

Generaal van den Boschweg

Cycle Road Near Dominee Germsweg

Forest near Fochteloerveen

Fochteloerveen

Norther Boarder

Third Asylum

Neighbourhood

Nowadays there are many ways to enter Veenhuizen as a visitor, by bus or by car. At least that is what I did. The Hoofdweg road feels like a gateway. Whereas when you drive into Veenhuizen from Een, you are embraced by the trees and suddenly find yourself in Veenhuizen. From Haulerwijk, you are welcomed by a stately cement statue with Veenhuizen engraved which also gives the feeling of driving into an estate or a ‘closed’ place. The fields in the area outside Veenhuizen are all similar however those in Veenhuizen give off a different look, they are slightly less bright as they are enclosed by trees.

The journey from Assen to Veenhuizen transforms from urban neighbourhoods to a rural landscape of squared fields bordered by trees. Observing from the bus, the scenery shifts to a collage of lawns, trees, houses, and long roads. The lock at Kolonievaart marks the entry into Veenhuizen, introducing a long road alongside a canal and a forest of pine trees. The route alternates between sparse houses and open meadows, creating a sense of entering a new space.

As soon as I stepped out of the bus, I felt like Alice in wonderland in a world somewhat unfamiliar to me. The pine trees near the canal gave me somewhat an uncanny feeling, as if they do not belong there, at least not in such a straight line.

I don’t know the exact history of the construction of Veenhuizen’s infrastructure but that the place was very wet does tell me that building roads and entering the place should not have been easy. Now the canal by the main road seems very peaceful whereas in the past it was really used as a waterway. Currently, it still serves as a cultural artefact and an instrumet to control the water. The build of the canal was one of the starting intervention in the build of Veenhuizen.

For me, Veenhuizen starts at the bus stop. Or actually any branched off road from the Hoofdweg which enters Veenhuizen. The main road almost forms a kind of wall on the right is Veenhuizen. If you see Fochteloërveen as part of Veenhuizen then you would say the main road is about the middle.

As I continue my way, this road feels like a red carpet to the prison museum. The houses with designations make me feel as if I have entered a theme park. As I see more people working in the front yard, an open garage door as a second-hand store, cyclists passing me and hikers accompanying their dogs, my feeling of a theme park is reduced and all I see is a small village with people outside.

The ducks and a few hidden coots have made their own home of the canal. This is the road where I have encountered the most people. The entrepreneurs established around this area clearly show how Veenhuizen has transformed to an open village. As if this never has been a prison village.

.

As I have reached the entrance of the museum, I first walk past a square that seems to be a gathering place for vacationers. They eat a sandwich on the bench and enjoy the sun.

Before I can make my entrance, I am greeted by two old trees, pruned however not to be missed. The clock above tells me the time. But as soon as I enter the building my time seems to stand still. Inside the building it is dark and feels cold. The longer I stay in the building or the inner garden, the more a feeling of unease stars creeping over me. On the other side as soon as I am out it feels like I can breathe again. I see people cycling, cars passing me by and there it is, the feeling of an inhabited village.

The square is pretty empty and there are some things I can’t quite place with how I feel. The police buses, the closed playground. As if different time zones have collided with each other. The emptiness combined with not being able to see beyond the walls of the squared building make me feel stuck.

Maybe it is because I know that this is one of the oldest buildings in the area. The empty garden gives me the chills. even the trees look lonely. During colony time there were around 1000 people living here that is far more that there will ever be at ones in Veenhuizen nowadays.

The road is higher than the environment it is connected to. It is straight and feels like it is never ending. While I am cycling this never-ending road gives me the idea of disorientation. There is nothing particular that catches my attention only the end of the bicycle road which seems like it is never going to end. Compared to other places in Veenhuizen this path feels free and open. Somehow, I feel I am not in Veenhuizen anymore.

As I cycle on, the forest patches speed past me. Sometimes I stop to see if I see anything in particular. Then the forest is abruptly broken up by a clearing. A spot which catches my attention, which then looked like a harvested field of potatoes. Later I discovered that from this place I could have seen the third asylum. The open feeling I experience when I look at the photo of the old photo of the third asylum is also what I experience when I cycle here.

From Kerklaan, you can cross Hoofdweg and walk straight into the forest that separates Veenhuizen and Fochteloërveen. What strikes me about the forest is that it changes in gradations from pine trees into birches under water. This forest feels scary like it is holding all the secrets. It is dark. However, the road ends quite fast and at the end you enter a wide open field, The Fochteloërveen.

In this forest it is dark and gives me an oppressive feeling because the smell of pine needles makes me feel at home except this place does not. I look around and I see row after row of trees in between growing some ferns. The path is accompanied by a canal with very dark water. The water is so dark because of the peat.

The path ends at a stretch where there is a dam with trees underwater. Where trees slowly die off to give space to the peat again, serving as a buffer zone for the Fochteloërveen. This shows how we as humans can still take care of an area. However, if you look at the height difference and take into account how the water wants to flow and where the water wants to stay. I would say the Bog wants to be bigger, it wants to grow. And now it is also growing but within the quays. Like a band-aid on a wound.

As soon as I enter the area from any direction whether it is, from Kerklaan straight ahead or when I cross Hoofdweg from Norgerweg. You will always meet some trees and will have to go through the forest to end up in Fochteloërveen. As soon as the forest is behind me, I feel free.

There is a cycle path through Fochteloërveen. I realise how impassable it is and imagine what it should have been, when Veenhuizen was just founded here. This place used to be unvegetated, open stretched, maybe a lost bush here and there, but no trees.

And as I let my thoughts wander for a moment, the realisation comes that Veenhuizen has been divided and chopped up into pieces and this is the only place where Veen still exists. Birds, dragonflies and the sky on the horizon reflects a different kind of vibrancy that you forget ever existed.

At the end of the Dominee Germsweg, I arrive at a waterfall. The sound of flowing water breaks the chilly silence that hangs there in some places. I continue my route. Here there is a forest on the right and a bumpy meadow which looks more like a moor, with a variety of trees on the horizon. The cycle path stops at a spot where I encounter a meandering stream. A tree on the bank that is dying shows that here nature makes its own choices. Here, too, you can see and feel a substantial difference from streets like Hoofdweg, Hospitaallaan and Generaal den Boschweg.

The fascinating thing about this area is that you again experience the difference between a forest on one side and a moor on the other. On the horizon a winding line of trees. There are trees characteristic of heathland deciduous trees. Furthermore, you can see the Slokkert meandering. As soon as you cross the Slokkert it feels like I can breathe again. The area is stretched out. You can clearly see the shapes of the stream valley. There is much more diversity on the horizon.

Before reaching this spot, I took a route from the north, passing through the forest. The landscape shifted abruptly from deciduous trees to dense conifers, creating an eerie sense of being watched. A sandy path led me past a striking and almost mystical place known as the Spanish Church, where the atmosphere changed—calmness settling in. Here, the structured rows of trees and occasional ditches reveal the forest’s planted origins.

At the end of the road, I emerged into a clearing where the old cotton spinning mill stands. As I continued toward the site of the third asylum, I noticed how the clustered buildings gave the area a communal feel. The open field appeared serene, lacking any immediate traces of the bleak, damp conditions that once defined life here. Perhaps time has softened the weight of the past, erasing the heaviness of what once took place.

From the Meidoornlaan, which contains the small working houses, you can take a turn to the Kerklaan, which also marks the beginning of Veenhuizen’s largest neighbourhood. From the Kerklaan you can see the outline of the new neighbourhood sometimes referred to as ‘the new settlers’. On a weekday, cars’ drive down the street and you can hear children playing in the background. Despite being located in the middle of ‘kanal pattern’, this place gives a sense of a community centre. There is real movement here. The people who gather here, the public amenities like a school, community centre and a church give an atmosphere of vibrancy.

The trees on the horizon made me recognize that there are things which are a bit off. I have collected horizons of the area. The trees can be seen as the guards of the area, standing in place not going anywhere. The trees are also not from this place, they came from somewhere else. Someone decided where they should grow and maintained it in that way.

The lanes are one of the main characteristics from the area. The lanes are the hallmark of this place, the business card. It gives a feeling of an estate. Only this time, the estate is so big that you feel the avenues never stop and, like a maze, going on never ending giving me the feeling of being trapped.

However, they do have some beauty in them mainly because the trees are so big and majestic. The light is shining through the places in-between the stems, like a window in a house.

The forest around this place made me feel less pleasant, I expected to have the same feeling in this place. However as soon as I took a longer time there, I felt carried like I am welcome here and I can stay here with my worries for a while. I took some pictures and later the pictures kept catching my attention. Another special thing about this place is that it is a historical place completely taken over by nature a hill overgrown by mosses and ferns, from which you cannot keep your attention away.

Veenhuizen is full of places where we intervene with how the landscape would like to grow. The ditches, the locks. Some are more visible than others. Here are the most recent, relevant, and most visible.

The effort put into preserving the active raised bog. The dams, the measuring instruments for research and the track to sustainably transport the sand through the area. This can be defined as a healing practice. However, you can also see this as a band aid because the peat has its limits. It cannot grow any further than the boarder.

The ‘natural’ history of the area surpasses the 200 years of history that Veenhuizen is characterised by nowadays. The essence of Veenhuizen lays in the material flows of the area, which became entangled with human efforts of altering the landscape and making it a habitable place for them. However, the grid like structure of Veenhuizen surpasses the idea of habitability it builds following an ideology. In some places in this area, you can still feel the atmosphere of the past.

The landscape slowly changes, and the place evolves with it. When nature is given space to grow freely, it transforms organically. But when we control it, shaping it to meet our expectations, the landscape reflects only what we maintain. The moment we step back, however, the land reveals its own rhythms, allowing new possibilities to emerge.

At first glance, this landscape appears diverse, yet beneath its surface lies a tapestry of hidden stories. One of them is the slow disappearance of a vast peat bog—an ecosystem that took centuries to form. It serves as a reminder that without mastering water, survival here was impossible. This mosaic of elements allows us to experience the passage of time embedded in the land itself.

Experiencing this place in all its complexity leaves me with two key questions: How do we navigate the tension between allowing nature to take its course and preserving cultural heritage? And what does it mean when cultural heritage is prioritized—does it reinforce the idea that human presence holds more significance than the natural processes of the land?

Through this research, I aim to honor the history of wetlands and highlight peat as an essential part of the stories of Veenhuizen’s colonies and the Rijkswerkinrichting. While human achievements are remarkable, so too is the resilience and diversity of an untamed, self-sustaining landscape.

1 De Clercq, Kathleen, Marja van den Broek, Marcel-Armand van Nieuwpoort, and Fleur Albers, eds. (2017) 2018. The Colonies of Benevolence. Translated by Joke de Groot. Royal van gorcum publishers.

2 Merriam-Webster. 2019. “Definition of TRAUMA.” Merriam-Webster.com. 2019. https:// www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/trauma.

3 The mindbodygreen podcast. 2022. “How to Understand & Heal Your Trauma: Gabor Maté, M.D. | Mbg Podcast.” Www.youtube.com. December 22, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=C-1Ukfaf7co.

4 Nail, Thomas. 2021. Theory of the Earth. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

5 Bron: Proulx, Annie. 2022. Veen, Dras, Moeras. Alexander van Gesteren en de Geus BV, Amsterdam 2022.

6 Proulx, Annie. 2022. Veen, Dras, Moeras. Alexander van Gesteren en de Geus BV, Amsterdam 2022. p. 116

7 Vries, Gerben de. 2025. “Landschaps Geschiedenis.” Landschapsgeschiedenis.nl. Kenniscentrum Landschap, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen. 2025. http://landschapsgeschiedenis.nl/deelgebieden/20-Smildervenen.html.

8 Jansen, Andre, and Ab Grootjans. 2019. Hoogvenen. Noordboek.p.9

9 De Clercq, Kathleen, Marja van den Broek, Marcel-Armand van Nieuwpoort, and Fleur Albers, eds. (2017) 2018. The Colonies of Benevolence. Translated by Joke de Groot. Oostersingel 11, 9401JX Assen, The Netherlands in cooperation with the programme Office Colonies of Benevolence Province of Drenthe. PO Box 122, 9400AC Assen, The Netherlands: Royal Van Gorcum Publishers. 10 InVeenhuizen punt NL. 2024. “Veenhuizen Op Het Randje van de Afgrond. GIDS in Veenhuizen.” YouTube. June 25, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jo8WjLbJF40

11 Drenthe, Provincie . 2024. “Groen Licht Voor Vervolg Pilot Veenhuizen.” Provincie Drenthe. 2024. https://www.provincie.drenthe.nl/actueel/nieuwsberichten/2024/maart/groen-licht-vervolg-pilot-veenhuizen/.

12 Natuurmonumenten. 2022. “Natuurmonumenten.” Natuurmonumenten. 2022. https:// www.natuurmonumenten.nl/natuurgebieden/fochteloerveen/natuurgebieden/achtergrondinformatie-natuurherstel-fochteloerveen.

13 Vries, Gerben de. 2025. “Landschaps Geschiedenis.” Landschapsgeschiedenis.nl. Kenniscentrum Landschap, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen. 2025. http://landschapsgeschiedenis.nl/deelgebieden/20-Smildervenen.html.

1. RCE, TNO, and Deltares. 2020. Paleografie 5500 V.Chr. Https://rce.webgis.nl/nl/map/erfgoedatlas. https://www. nationaalgeoregister.nl/geonetwork/srv/dut/catalog.search#/metadata/c63138f8-775a-4ca2-907c-31f44bd2abf4

2. RCE, TNO, and Deltares. 2020. Paleografie 2750 V.Chr. Https://rce.webgis.nl/nl/map/erfgoedatlas.

3. RCE, TNO, and Deltares. 2020. Paleografie 1500 V.Chr. Https://rce.webgis.nl/nl/map/erfgoedatlas.

4. RCE, TNO, and Deltares. 2020. Paleografie 800 na Chr. Https://rce.webgis.nl/nl/map/erfgoedatlas.

5. Pijnacker, Cornelis , and Drents Archief. n.d. 0602.01 Heren van Hoogersmilde: Lijst van Kaarten En Tekeningen. Beeldbank Drents Archief. Https://Www.drentsarchief.nl/Onderzoeken/Kaarten?Mivast=34&Mizig=181&Miadt=34&Miview=Ldt&Milang=Nl&Miej=1650&Mizk_alle=Drenthe.

6. RCE, TNO, and Deltares. 2020. Paleografie 1250 Na.Chr. Https://rce.webgis.nl/nl/map/erfgoedatlas.

7. RCE, TNO, and Deltares. 2020. Paleografie 1500 Na.Chr. Https://rce.webgis.nl/nl/map/erfgoedatlas.

8. RCE, TNO, and Deltares. 2020. Paleografie 1800. Na.Chr. Https://rce.webgis.nl/nl/map/erfgoedatlas.

9. RCE, TNO, and Deltares. 2020. Paleografie 2000 Na.Chr. Https://rce.webgis.nl/nl/map/erfgoedatlas.

10. Plaatje in hoofdstuk political structures: BGT Voor de Eigendom Verdeling in Veenhuizen. 2024. Basisregistratie Grootschalige Topografie (BGT). https://www.geobasisregistraties.nl/basisregistraties/grootschalige-topografie.

11. Map based on: Screenshot of location map(s) based on: “OpenStreetMap.” 2025. OpenStreetMap. 2025. https:// www.openstreetmap.org/#map=8/52.154/5.295.

12. Processed picture based on: [onbekend ]. n.d. Vooraanzicht van Het Tweede Gesticht, Nu Het Gevangenismuseum, Aan de Generaal van Den Boschweg Te Veenhuizen. Rechts van Het Midden de Alarmpaal, Een Mast Met Een Alarm Installatie. Drents Archief. Gevangenismuseum. https://www.drentsarchief.nl/onderzoeken/beeldbank/zoeken/detail/36d2fdb6-76d5-44cd-93d6-1173286a566e/media/aabfd5fc-2c79-4eac-a6a3-5d5750120d01?mode=detail&view=list&q=Gen-

eraal%20van%20den%20boschweg&rows=1&page=5&sort=order_s_begin_eind_datum%20asc. 13. Kerklaan [onbekend ]. n.d. De Voormalige Rooms Katholieke Kerk (Links Op de Foto) En de Nieuwe Rooms Katholieke Kerk Aan de Kerklaan Te Veenhuizen. Drents Archief. Collectie Provinciale Monumentenzorg. Accessed January 20, 2025. https:// www.drentsarchief.nl/onderzoeken/beeldbank/zoeken/detail/46455d6c-a241-4346-8e34-a13c22b28425/media/4c6166f9 -3c60-4ecf-b09f-26a1bbbe6154?mode=detail&view=horizontal&q=Kerklaan&rows=1&page=4&fq%5B%5D=search_s_ plaats:%22Veenhuizen%22&filterAction.