13 minute read

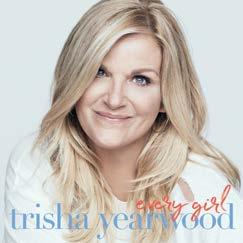

COVER STORY: TRISHA YEARWOOD Over her long

BY WARREN DENNEY

The first thing you hear is her heart. Trisha Yearwood is one of those singers, at the ready to work through the world, good or bad, sympathetic to the right fight.

continued on page 22 Her voice cuts through the noise — emotional, powerful, elastic, and she sings about heartbreak, longing, and exhilaration with honest bearing. Yearwood can go anywhere with a song, and through that emotional carry, she delivers kinship. To tell the story, you must feel the story.

“As a young girl, before I had any real life experience, I was dramatic,” Yearwood said from home, just before Christmas. “I’d sing those [Linda] Ronstadt songs like I had a broken heart — when I had never even kissed a boy. But still, it meant so much to me. And I was always drawn to songs that commiserated with you. When you want to go down that rabbit hole, or you’re feeling like your life is a mess, you want to hear a song that says, ‘Yeah, I get it. I’m there, too.’ You want to hear a song that says, ‘Oh my God … here’s how I feel.’”

Yearwood, of course, does get it. She has been translating the everyday, alongside the divine, in a career that spans three decades. Her first record, Trisha Yearwood, released in 1991, caught the world off-guard and yielded the monster No. 1 hit “She’s in Love with the Boy.” Yearwood became the first female country singer to have a debut album sell a million copies in its first year. She joined Local 257 on July 30, 1991, and is now a 28-year member.

Her belief in herself, and faith in others, too, brought her to that original place. She understands doubt and crises of confidence — and exhilaration. You hear it. The release of Every Girl last August, her first solo effort in twelve years, signaled a reaffirmation. Her life has certainly been full, but the focus was not squarely on her music.

Certainly, she is more than that music — actress, author, celebrity chef, household name — but at the root of all which has made her, she is a singer with an extraordinary gift. Life in the public eye came at her quickly, and she has refined a professional balancing act ever since. In recent years, Yearwood has published three insanely popular cookbooks, and established the award-winning television show Trisha’s Southern Kitchen on the Food Network. Because she has the ability to fit seamlessly into American popular culture in so many effective ways, it might be easy to forget the absolute power of her voice. She’s played a Navy coroner in the television series JAG, and starred in a Peter Bogdanovich movie, for God’s sake.

continued on page 24 “Well, I made my first official album when I was 26 years old, and that’s all I’d ever wanted to do — was to sing,” she said. “And so, I felt very lucky to get to do that. I think what I’ve done in the last 10 or 12 years — the other things that I do — the cooking show and the cookbooks, were all an accidental second career. I wrote a cookbook because I’d moved to Oklahoma to help [husband] Garth [Brooks] with the girls, and I wasn’t working at all.

“I wasn't touring, and I was at home and I needed to find a way to be creative. So, I would work on the books at night when the girls would go to bed, and I never dreamed it would turn into another whole career — I never dreamed this would happen. It’s time-consuming and it’s something that I really enjoy. Then Garth did the world tour and I was part of that, so that was almost four years. And, when I wasn’t touring with him, I was doing the show. It was kind of like — I looked up one day and 10 years had passed without me making a new album of music.

“It was a big reminder for me when I went in the studio to work on this album — just how much I need to do this to feed my soul.” The result was powerful, not only for the listener, but for Yearwood, too. She has referred to her relationship with music as a calling, not a choice.

“It’s not just something I do because I want to be famous, or I want to make money,” she said. “I like those things, but I do this because it’s something that is important for me to do — to feel like me. And it was a good reminder, too. I don’t need to let that much time pass. Life is short and you don’t know what’s going to happen in 10 years. I don’t want that much time to pass again because being creative and being in the studio is so fulfilling to me. I really had missed it.”

Yearwood’s music has always tilted to a rocking country feel, with a heavy dose of blues counterpoint when needed, as delivered on Thinkin’ About You in 1995 and Everybody Knows in 1996, which yielded two No. 1 hits “XXX’s and OOO’s (An American Girl)” and “Believe Me Baby (I Lied).” She won her first Grammy in 1995 for Best Country Collaboration with Vocals for her duet with Aaron Neville

on Patsy Cline’s “I Fall to Pieces” from the Rhythm, Country and Blues compilation of R&B covers recorded by country artists.

In total, Yearwood has earned three Grammys, including Best Female Country Vocal Performance in 1997 for “How Do I Live,” and for her vocal collaboration with husband Garth on “In Another’s Eyes” the same year. Both songs appeared on (Songbook) A Collection of Hits, the greatest hits album that reached No. 1 on the Billboard country charts. She was named the Country Music Association’s Female Vocalist of the Year in 1997 and 1998. She earned the Academy of Country Music’s Top New Female Vocalist in 1991, followed by Top Female Vocalist in 1997. With the release of Every Girl, Yearwood has reanimated that voice. And, in doing so, she has returned to her touchstone. Beyond the 2007 holiday-themed Christmas Together recorded with Garth, Every Girl is the first real solo offering since Heaven, Heartache, and the Power of Love. She did record Let’s Be Frank in 2018, a collection of classic Sinatra covers at the Capitol Records studio in Los Angeles. Additionally, she had joined Brooks in 2014 on a daunting and hugely successful three-year world tour. She believes that time away informed her perspective and the approach to her own thing.

“I definitely think so,” she said, laughing. “I turned 55 [last year] and if I had a filter before, it’s gone. I kind of recommend losing that filter highly — that good old Southern girl who doesn’t want to offend anybody and worries about what everyone else thinks.

“And also, being in an industry that’s very much about, ‘Well, what have you done lately? You're too old to do this. And you’re a woman — we’re not going to put that thing on the radio.’ To make a record now, there’s a freedom that comes with it. I don’t have any rules. I can go in, find songs I love. I don’t have anybody to please except me.

“When it’s done, we can figure out different ways to get the music out there. I knew we had a big following for the cooking show. I knew we had an audience. Country music — fans who love country music — they don't stop being fans. I think we have the best fans of any genre. They are loyal. [With Every Girl] I wasn't worried about exactly how we were going to do it. I just knew that we were going to figure it out. That freedom to just go in — just have fun and make a record — it’s something I might not have felt if I had made one right after the last one 12 years ago.”

The record, produced by longtime compatriot Garth Fundis, moves from the reflective to the anthemic, with emotions bared. Whether it’s the broken-hearted cry of the opener “Workin’ on Whiskey” or the got-your-back slice of American life with “Every Girl in This Town,” Yearwood lifts mundane living to a higher plane. Of special note is the cover of Karla Bonoff’s “Home,” made popular by Bonnie

Raitt. Yearwood absolutely nails the plaintive inspiration found there. There are potent collaborations found, as well, with tracks like the bluesy lament “What Gave It Away,” sung with Garth, the simple “Bible And A .44” sung with Patty Loveless, the personal and powerful “Tell Me Something I Don’t Know,” with Kelly Clarkson, and the aching “Love You Anyway,” featuring Don Henley.

“I’ve always been drawn to those kind of songs,” Yearwood said. “I like an underdog … especially in songs like 'Every Girl in This Town,' I love that it says, ‘You’ve got this baby, so what if you don't?’ I think it’s important to say, ‘We’re all going for the same thing here. We're all trying to put on our best face.’ Sometimes we don’t. And that’s okay too.

“And I think we need to be told — especially girls — because I think girls in particular are hard on themselves and they're hard on each other. When you’re really young, you think you can do anything. Then, in your early teens, you start to doubt yourself and listen to what other people say. So, to remember that feeling of ‘It's okay if you don’t have it all together.’ I like songs that speak to that — the humanness of who we all are.”

Possibly, it is that sense of empathy which resides at the core of Yearwood the artist. From the moment she knew she was different, growing up in Monticello, Georgia, she has relied on the range of emotion in her voice to take her anywhere. She listened to everything, giving herself the musical foundation that still thrives — when awakened.

“Yeah, I think it just comes out,” she said. “I like a lot of different kinds of music. And so, whatever the song seems to feel, is just what comes out. It’s not really a plan. Linda Ronstadt’s my person — she’s the reason I wanted to be a singer. And Linda was that artist who — when I was a kid growing up in the ‘70s — they were playing on pop radio, rock & roll radio. But, you hear the steel guitar and fiddle. And, she leaned into the country thing, although she wasn't played on country radio then. I grew up on it.

“And, that introduced me to Emmylou [Harris] and to Bonnie Raitt. And so I’ve always had those influences there. I think most artists naturally end up picking a genre that they kind of fit into the best. We all like different things. So, I think that my voice can go bluesy … that kind of thing. But, it wasn't like, ‘Oh, let’s try to make your voice do this.’ If I love a song, let’s shake it out.”

The American musical landscape was more democratic, less surgically dissected.

“It was definitely a time when music seemed to be a lot more open,” Yearwood said. “There weren’t as many boxes put around what you sang, or what you did, exactly. And, I love country music too, and I felt like this is where I landed. It’s interesting — when I started making records in the early ‘90s, I was not considered traditional country. I was not. But now, it sounds more traditional in a sense. Everything just goes in cycles like that.”

Yearwood has persevered and succeeded in a town that might often care less about who you are than what you are. The commodity of music in the digital age always threatens to cheapen it, even as it disseminates it more globally. Nashville is literally packed with hopefuls who may not know how to dig deep. In other words, more of a choice than a calling.

“There are two sides of the coin that have always existed in this town,” she said. “There are artists who can’t be anything else. Like Emmylou. To me, she set the bar. She is the definition of an artist being true to herself. I’ve asked myself before, ‘What would Emmylou do?’

“The other person I think of is Linda Ronstadt. I got to be a part of honoring her at the Kennedy Center, and I was listening to Don Henley talk about all of her accomplishments — everything she’s done. And I sat there and thought, ‘This is why I am how I am, because this woman, she never compromised her artistic integrity.’ When she went against her record label to do an album of standards. They thought it was a terrible idea, and it did great ... she’s the definition of an artist. She’s followed her path and hasn’t worried about what was going to happen.”

To Yearwood, the commercial byproducts of artistry aren’t the point. “What can come out of that — fame, fortune, record sales — that’s all well and good, but that’s not the reason I cut this song,” she said. “That’s not the reason I wore this dress … all of those things. There are always going to be people coming here to seek fame first. There’s always been an element of that, but I think it’s even more so now because there are bigger, different ways to do it. You can go to YouTube and make a name for yourself. You might go on The Voice or American Idol and be famous before you’ve even put out a record. “There have been great country artists in the past who have put out three or four records before having their first hit. I’m not sure they would get that opportunity today.” Yearwood certainly understands the drive behind each side of the coin. Hillbilly Babylon has it all. But, like Hollywood, dreamers are drawn here, and that in itself drives artistry, regardless of motivation. Nashville sits squarely at the intersection of high art and an oft-times colder reality.

“I’ve always loved it [Nashville],” she said. “There’s always the appeal. True artistry and talent may not be the first things at the top of the list when they’re putting acts together for small-town kids who want to make it big. But, then the flip side of that is, you'll have someone like Chris Stapleton come to this town and be under the radar for years, writing songs, doing demos. You listen to the demos to hear Chris Stapleton sing. Then good things happen for him. So, there is a true artistry that no matter what people do — you can’t put down. It’s there. My hope is that the good stuff will always be there. There’s so much talent in this town that no one knows about. It’s amazing.” By returning to the fore with Every Girl, Yearwood has reclaimed ground, and rekindled a fire. But, it’s not about one record. She has found, once again, what many of those dreamers are looking for.

“Making this record felt so good,” she said. “I’m hoping when people hear it, that they hear the joy.” TNM