28 minute read

The Medical Implications of Combat T’ai Chi Ch’uan Techniques: Investigating Blunt Force Trauma - Part 3 Dr. Gregory T. Lawton

from Lift Hands Magazine Volume 15 September 2020 - The Multi-Award Winning Magazine of the Year 2019

by Nasser Butt

The lowliest ant busied in the dirt knows this truth, how is it then that you do not?

Translated From A Foreign Tongue

his article on The Medical Implications of Combat Tai Chi Chuan, Investigating Blunt Force

TTrauma, Part 3, has been preceded by Parts 1 and 2. If the reader of this article has not read Part 1 or Part 2 of this series, it is recommended that they first review those two articles. Part 1 of this series on The Medical Implications of Combat Tai Chi Chuan Techniques, Investigating Blunt Force Trauma was an introduction to several techniques which included sealing the blood, sealing the breath, displacing the bone, bone fractures, and gouging, or hooks and the significant medical consequences of these techniques. In Part 2 of this series we investigated the physiological effects of various strikes to the human body systems, such as the circulatory and nervous systems and their anatomical components. Additionally, the parts in this series are being written in sequence from greater to lesser physiological damage inflected on an attacker’s body. Therefore, the techniques described in Parts 1 and 2 have the potential to do more physical harm than the techniques covered in Part 3. Properly executed Combat Tai Chi Chuan techniques, which are firmly based upon the essential principles of classical Tai Chi Chuan, represent the authentic practice of Tai Chi Chuan in reality-based offensive and defensive applications for the purpose of selfdefense.

The writing of this series was begun prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and the violence that has been escalating in cities around the world but it was written with an awareness of increasing violence resulting from unarmed and armed attacks on innocent citizens world-wide and an awareness of the growing potential for increased violence that could occur in the coming months on unprecedented levels. Increasing numbers of individuals are being attacked, injured, and killed on the streets, on their way to work, at family and public gatherings, in parks, in their automobiles, and in their homes. Many of the attacks against individuals are from muggers, criminals attempting home invasions, violent protesters, rioters, and looters whose attacks against others are often unprovoked. The attackers are employing weapons of opportunity such as rocks, bricks, sticks, and street signs, but guns and knifes are ubiquitous in many cities and so injuries and deaths from these weapons are skyrocketing. People who formerly espoused gun control reforms are now arming themselves (In countries where they are allowed to own guns) at unprecedented levels and guns and ammunition are in short supply.

These worldwide events with escalating violence in our cities place the question of the moral appropriateness of reality-based self-defense in a clarifying context. Where criticism of self-defense techniques whose prime purpose is to incapacitate, maim or to kill an attacker frequently faced moral condemnation, those arguments have dimmed in the shadow of rampant social unrest and violence. Considering the obvious decline in society and the decay of existing institutions of governance, justice, public safety and education, there is every reason to believe that the need for personal self-defense training will greatly increase in the immediate future.

The most effective self-defense techniques are those that are the simplest to execute and those that are based upon the fewest but most efficient movements. I call this approach “effective simplicity”. The more esoteric or complex a self-defense technique is the less likely it is to be effective. Therefore, in many cases, a welldesigned self-defense program is better at preparing students to defend themselves and their families from an attack than years of martial arts training. The original foundation of most traditional martial arts systems is based on lethal combat techniques and Tai Chi Chuan is no exception. Unfortunately, many Tai Chi Chuan students and practitioners have not trained in the combat aspects of their art and therefore they lack these skill sets. Several times in this article I will quote this military adage, ““Remember, you will fight as you train!” Where a marital artist trained in light or limited contact kumite, san-sau, or sports fighting may kick an opponent in the thigh, a martial artist whose art includes Chin Na will attempt a thrust or kick intended to shear through the ligaments, menisci, and connective tissues that attach the femur to the tibial bone. If a student is “realistically” trained, they will execute an attack without moral hesitation or concern for “rules”.

Let us review several of the essential elements of the application of effective self-defense techniques. elements These elements include:

1. Embrace the concept of effective simplicity. 2. Practice a few well-honed and effective attack sequences and combinations. 3. Practice your techniques once for form and flow, once for strength and power, and once for speed. When you practice at full speed do so with form, flow, strength, and power. 4. Offensive and preemptive attacks – if you perceive that you are going to be attacked do not wait for the attack, but rather initiate an offensive attack. 5. Deliver an attack that is the most decisive and destructive that you can deliver. 6. In self-defense there is only one speed, blindly fast. 7. Self-defense has no rules or limitations. When you are faced with an attacker who is threatening your wellbeing or life you are morally and legally justified in answering the threat with extreme violence to the point of incapacitating the attacker. 8. Use all the self-defense tools that you have been trained to use, your fingers, hands, wrist, arms, shoulders, head, hips, knees, legs, ankles, feet, and even your teeth. 9. Do not waste effort or time on attacks that will not maim or completely incapacitate an attacker. 10. Never fight on equal terms and counter whatever skills, abilities, or weapons an attacker brings to the fight with a greater counterattack. 11. If an attacker or opponent has superior skills, is larger, taller, heavier, and younger, use an appropriate weapon to defend yourself. 12. Be aware of and use the environment that the attack is occurring in including the walls, windows, poles, sidewalk, and every solid object that an attacker can be pushed or thrown into.

“When the opponent makes the slightest move, you move first”. Yang Family Secret Transmissions Compiled and translated by Douglas Wile

A word about the practice of Tai Chi Chuan. Many students of Tai Chi Chuan never learn to perform their Tai Chi Chuan form at full speed but continue to practice in the slow meditative style that is so common. Once you have learned a Tai Chi Chuan form to become proficient at fighting you must be able to perform the form at full speed and in addition you must practice the various Tai Chi Chuan postures over and over again as training drills and you must practice the postures applications with the three characteristics of form and flow, strength and power, and speed. Another word of advice, do not sacrifice speed for strength. If I had to chose between speed and strength. I would always chose speed. Remember, as little as, “Four ounces can move one thousand pounds”, especially if that “four ounces” gets to its target first!

Look into the technique of using four ounces of energy to control the force of a thousand pounds. Such techniques as these do not depend upon brute force to overcome. Tai Chi Classics, Waysun Liao

X-ray of dislocated knee Source: Duprey K, Lin M. Posterior knee dislocation. West J Emerg Med. 2010;11(1):103-104.

In the x-ray image above, we see a posterior dislocation at the knee. This injury can be induced by a strong thrust or kick to the anterior surface of the knee joint at or below the patella which is at the junction of the femur and the tibial bone. A dislocation of this severity and degree will completely shear and detach the ligaments of the knee. Such an injury will result in extreme pain and an inability to bear weight on the joint or the leg.

The most effective means of destroying a joint is to create a fulcrum point against a “bony landmark” on your own body and to destroy the joint capsule by forcing the joint to bend in a direction and degree of motion that the joint would not normally bend to. A bony landmark is a location on a joint that provides a firm “table” over which you can effectively apply force to an attacker’s joint. In the demonstration photographs to follow I am demonstrating trapping a kick and creating a fulcrum point against my forearm and hip, but you can use any firm bony surface by which to destroy a joint. In addition to using a fulcrum you should also twist or “split” the attacker’s joint. When you do this you are using both torque and shearing to dislocate the joint and to tear the ligaments and tendons of the joint capsule.

Trap the extremity, create a fulcrum, twist, torque, or “split” the joint.

Driving a shearing force (elbow) through the joint to dislocate and destroy the joint capsule.

Like many martial arts instructors I have taught students self-defense who have been the victims of vicious attacks, incidents of physical assault, or domestic abuse. While the reader may think that my methods are extreme and that this approach is too violent, I am reminded of the young female student that I trained who was raped in her home by two men, at knife point, and in front of her eleven year old daughter and husband. I believe that she would disagree with you.

Many traditional martial artists enjoy the esoteric, metaphysical, and philosophical dimensions of their art and the many benefits that are derived for their mind, body, and spirit, but it must not be forgotten that the authors and originators of these arts were themselves fierce fighters and warriors who lived, not unlike today, in a time of lawlessness and violence. The growth of the martial arts was nourished and watered by the need for personal and family protection. That need still exists today.

The context of this article, and the previous two parts of this series, is that situational awareness, avoidance, and de-escalation has failed, and you are now in a life and death self-defense situation. Therefore, the techniques that are described in this article are designed to preserve your life, or the life of someone else. As a martial arts instructor to have a student reach this point and realization means that everything that I have attempted to inculcate within them in terms of preserving the peace, avoiding violence, and that “It is better to heal than to harm” has failed. In this kind of situation force is justified, warranted, and perhaps the only way that you will survive. To prevail you must persevere mentally and physically and be willing to escalate the violence to the point of incapacitating your attacker. If violence must occur do not hesitate to inflict it. From the words of one of my teachers, “Never enter a fight without the intention to kill, and the willing acceptance of your death. But do neither, do not kill and do not die.” The meaning of these words is to never face an opponent in any contest without the expectation of death, even in the most benign of encounters. This attitude speaks to the heart of the martial spirit.

It is recommended that anyone who believes that they may be placed in a situation where they have to employ maiming or lethal force should educate themselves regarding their local or national self-defense laws and the legal consequences of injuring or killing an attacker. For example, in some legal jurisdictions you have the right to preemptive offensive actions if you believe that your life is endangered. While you may have the legal right to defend yourself there is a definite legal distinction between acts of self-defense to the point of incapacitating your attacker and being able to withdraw from an attack and crossing the line from self-defense into engaging in “combat”. In many legal jurisdictions, although you may have first been the victim of an attack, if you cross the line into combat you have become an aggressor and both you and your attacker will be subject to legal sanctions. As many legal advisor’s state, “The first fight is to defend yourself or those you love, the second fight is the legal battle that will often follow the incident”. The second fight may be against criminal charges or defense against a civil lawsuit from your attacker or their family.

Chin Na and the Traditional Martial Arts:

Traditional Chinese martial arts, including both internal and external systems, contain Chin Na techniques intended to seize, hold, or lock joints. For those readers unfamiliar with Chin Na technique, applications, and terminology these are the board categories:

1.

2.

3. "Fen jin" or "zhua jin" (dividing the muscle/tendon, grabbing the muscle/tendon). Fen means "to divide", zhua is "to grab" and jin means "tendon, muscle, sinew". They refer to techniques which tear apart an opponent's muscles or tendons. "Cuo gu" (misplacing the bone). Cuo means "wrong, disorder" and gu means "bone". Cuo gu therefore refer to techniques which put bones in wrong positions and is usually applied specifically to joints. "Bi qi" (sealing the breath). Bi means "to close, seal or shut" and qi, or more specifically kong qi, meaning "air". "Bi qi" is the technique of preventing the opponent from inhaling. This differs from mere strangulation in that it may be applied not only to the windpipe directly but also to muscles surrounding the lungs, supposedly to shock the system into a contraction which impairs breathing.

4. "Dian mai" or "dian xue" (sealing the vein/artery or acupressure cavity). Like the Cantonese Dim Mak, these are the technique of sealing or striking blood vessels and chi points.

Historically, and for military applications, original traditional martial arts systems contained strikes and grappling techniques intended to maim or to kill. For the purposes of sports competition these techniques were removed or watered down to the point where succeeding generations of marital artists either did not receive realistic training in these techniques or they had little or no practical experience in their application.

In Chen Pan Ling’s Original Tai Chi Chuan Textbook, translated by his student Y.W. Chang Chen, Pan Ling wrote, “In ancient times, Chinese martial arts experts knew physiology very well. They used hit-vital point (tien Hsueh) to destroy the nervous system, to stop chi and blood circulation,,., and to damage the internal organs of the body. They used catch-and-snap technique (chin na) specifically to damage muscles, irritate sinew points and tendons, and to control the functions of the joints.” Chen Pan Ling then continues by stating, “If you do not know physiology well it is impossible to use such extraordinary techniques. He then continues his discussion by explaining how to train in these techniques.

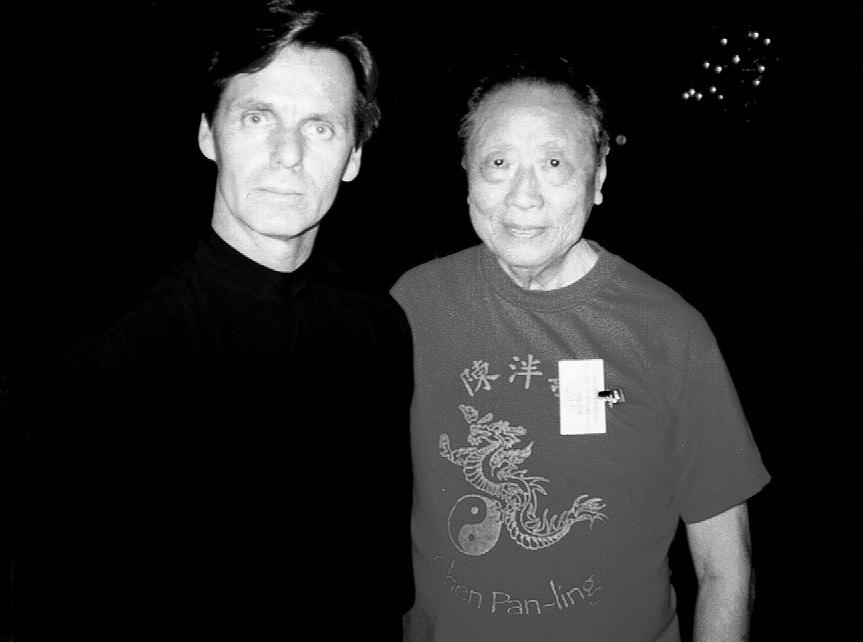

Photo of the author with Y.W. Chang student of Chen Pan Ling and the authorized translator of his book, Chen Pan-Ling’s Original Tai Chi Chuan Textbook

In this era of “mixed martial arts”, the traditional martial arts have been the recipient of criticism by amateur sports martial artists who fight for titles and trophy’s and professional sports fighters who compete for titles and money. Of course, unless a fighter is visiting from another planet all fighting systems practiced today originated from one or more traditional martial arts. There are those who like to point out that traditional martial arts and martial artists frequently do not do well in sporting contests against contemporary mixed martial artists. However, there are numerous examples of traditionally trained marital artists who have successfully “crossed over” from the traditional martial arts to contemporary sport fighting.

There are many reasons for the poor performance of some traditional marital artists who attempt to compete against fighters in mixed martial arts competition. Some of the reasons are related to poor training and conditioning, lack of complete training in a traditional martial art system where vital training such as Chin Na training has been omitted, and unrealistic or delusion thinking regarding the esoteric applications of complex traditional fighting techniques. Perhaps the main reason is that in order to compete in modern sporting contests a traditional martial artist must adhere to a set of competition rules that strip away the maiming and killing techniques that have been the foundation of most traditional martial arts for centuries. Remember the adage, “Never play another man’s game” and the military mantra, “Remember, you will fight as you train!” If you train to grapple and to strike avoiding lethal and maiming anatomical areas of the body that is how you will fight in a high stress encounter. There is a significant difference in the mental intent of attacking an elbow joint to dislocate it and to rip its ligaments apart as opposed to attacking the joint to lock or control it in the hope of obtaining a submission to win a sporting contest.

An important aspect of becoming a successful, effective, enduring, and capable martial artist is found in the moral balance and the physical health of the fighter. Too many martial artists and sports fighters have succumbed to their baser instincts, passions, and behaviors. Martial arts competitors in the amateur and professional fighting sports are seduced by short term glory and rewards and sacrifice their health and physical abilities to steroids and other performance enhancing drugs. The demands of preparing and training for professional competition and then engaging in the extreme violence that is glorified in sports fighting contests rapidly expends the talent capital of young martial artists. Hence, we witness the revolving door of sports fighters who have their 15 minutes of glory only to end their careers with a catastrophic injury. Most concerning among the long list of musculoskeletal and central nervous system injuries that sports fighters experience are 56

traumatic brain injuries, dementia, and Parkinson’s disease.

It is not so much the system or style of martial art that a man or woman practices that determines their capabilities as a fighter. It is rather their moral balance and physical conditioning. If a fighter cannot control their baser instincts, vices, and addictions they will not last long as a fighter, they will sacrifice their personal health and wellbeing. I frequently share this statement with my young students, “The vices and addictions that you do not overcome in your life will be the cause of your death, but before you die, you will slowly lose your abilities and capabilities, you will lose the things that you enjoy doing in life, and you will watch them fade away.”

If you are observant and consider the decline of many aging marital artists few personify good health habits and consequently by their 4th or 5th decade of life, they have experienced serious health problems such as obesity and have lost their physical capacities as martial artists. Aging is inevitable but most “aging” is neglect, the result of poor diet and lifestyle habits, and a lack of proper physical conditioning.

Misplacing the Bone, or Destruction of the Anatomical Joint Complex

In this article, Part 3, we are going to investigate the application of extreme hypermobility to the joint complex involving traction, torque, and shearing forces directed at joints. The normal movements of a joint occur around an axis which involves joint physics. Joint physics may be defined as traction, torque, shearing, and accommodation, and involves flexion, extension, adduction, abduction, circumduction pronation, supination inversion and eversion. These movements are known as joint range of motion and they are normally measured in degrees of movement within the distance and direction that the joint can move. Range of motion is restricted by the anatomical architecture of a joint, mainly its capsule, ligaments, and tendons.

The joint complex is comprised of the bones of the joint, usually two, the joint capsule, ligaments, muscles, and tendons. In addition, each joint and its anatomical components will have nerves and blood vessels. All this anatomical architecture from the bones to the soft tissue structures is vulnerable to attack. Depending upon the technique used and against what kind of anatomic structure it is being used against there is the potential for an attack to result in destruction of the integrity of a joint, extreme pain, and permanent disability.

The human body contains 206 bones that are held together by connective tissues such as ligaments and tendons. Over half of the bones in the body are contained in the hands and feet. Bones meet or are joined at a joint and there are hundreds of joints in the human body, some moveable and some immovable. From a fighting perspective we are primarily interested in the major joints that can be dislocated through the destruction of the joint complex with a tearing of the connective tissues that hold the bones of the joint in place. Using the shoulder as an example, the shoulder is the most mobile joint in the body, and it is held in place by the rotator cuff tendons. Techniques that serve to dislocate the shoulder joint will frequently cause a full or partial tear in the rotator cuff tendons and a dislocation of the shoulder joint.

Learning to dislocate a joint and to destroy the joint complex requires basic knowledge of the anatomy and physiology of joints and the limits of their normal range of motion. Anatomy and physiology of joints should be a routine part of the education of a martial artist. In addition to learning about joint anatomy and physiology martial artists need to know the kinesiology (science of body movement) or range of motion of a joint because the destruction of a joint will be accomplished by moving the joint beyond its normal range of motion. One example, again using the shoulder, is to move the shoulder joint into extreme hyperextension which will separate the head of the humerus from the glenoid fossa tearing the rotator cuff tendons and the ligaments of the joint capsule.

The following images demonstrate techniques to dislocate the shoulder joint tearing the rotator cuff tendons and the ligaments of the joint capsule. The first photograph shows a standing arm lock to shoulder dislocation, while the second technique employs a “Guillotine choke” with the radial bone applied to the attacker’s airway and positioned to crush the airway. The next step is the dislocation of the shoulder joint. Many of the major bony landmarks of your body can be used as natural surfaces over which to bend and destroy an attacker’s joints. Learn how to use them effectively.

Applying the standing arm lock to dislocation of the shoulder joint.

Application of a “brachial stun” to setup the entry for the Guillotine choke and radial bone airway crush.

Demonstration of the Guillotine choke with the edge of the radial bone applying pressure to the airway, while dislocating the shoulder to destroy the joint capsule.

X-ray of dislocated shoulder Source: Hellerhoff / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)

When a sports grappler is attempting a joint lock, the technique is normally applied with increasing strength and pressure against the joint until the “end range” or limit of the range of motion of a joint is reached. Upon reaching the joints end range the martial artist will feel resistance in the joint and the attacker will begin to feel pain. This is the point in sports fighting where the opponent will submit.

Within a self-defense scenario the joint technique is not applied with gradual strength or pressure into the joint, but rather with a sudden explosive manoeuvre of the joint that quickly moves beyond the joints end range or the limit of the joints range of motion. This sudden explosive movement destroys the connective tissue attachments of the joint detaching and tearing the ligaments and tendons that are attached to the joint.

The set up and application of a joint lock in a sports contest is significantly different than that which may occur in a self-defense scenario where the purpose is not to “lock” the joint or to force a submission but rather the intention is to destroy the integrity of a joint as quickly and forcefully as possible. For example, in practicing the Japanese art of Aikido, first control involves a wrist and an elbow lock with a takedown to submission. In the Korean martial art of Hap Do Sool a wrist lock is combined with rapidly and powerfully driving an elbow through the elbow joint, dislocating the joint and tearing ligaments and tendons from the bone. The Aikido technique is elegant and “nonviolent” and the Hap Do Sool technique is brutal, violent, and effective.

Store energy like drawing a bow; release it like shooting an arrow. Yang Family Secret Transmissions Compiled and translated by Douglas Wile

Demonstration of an elbow break by drawing the wrist lock to my waist hip bone to create a fulcrum and then driving my forearm through the attacker’s elbow joint.

Once again, I am demonstrating the concept of creating a fulcrum over which to destroy the attacker’s joint capsule. In this photograph I am rotating my waist to break the attacker’s elbow joint against the natural curvature of my rib cage.

Dislocation of the Fingers and Thumb:

Opportunities to dislocate and separate the joints of the fingers, the metacarpal bones, and the thumb may occur when an attacker has grabbed on to a victim such as in a bear hug, choke hold, or any attempt to restrain a victim by holding on to their arms, wrist, or hands. In recommending an attempt to dislocate or separate the metacarpal bones of the fingers and thumb we are assuming that because of the position that the victim is in, other more lethal or maiming attacks are not practical, for example, crushing the attackers airway, gouging into an eye socket, dislocating the mandible, or grabbing and crushing the genitals.

Some traditional martial arts teach complex finger, hand, or wrist techniques and the more complex the technique is the less likely it is to be effective. If you study the anatomy and the range of joint motion in a finger joint, the metacarpals, you will learn that they have excellent range of motion in flexion but limited range of motion in extension. A finger placed into hyperextension is very vulnerable to dislocation, separation, and complete detachment of the ligaments that hold the metacarpal joints together. Depending upon the attacker’s grip and hand position the thumb is often the easiest of the digits to dislocate. Finger dislocation and separation is also very painful. However painful finger or thumb dislocation cannot be relied upon to stop an attacker in every circumstance which is why if a finger dislocation is executed against an attacker an immediate more effective follow-up technique should also be employed. There are many scenarios were pain alone is not an effective deterrent to stopping an attacker. High levels of adrenalin and street drug use are two examples where an attacker may be impervious to pain. This principle of following one disabling attack with another is called “continuous” attack and it involves attacking until the attacker is on the ground and incapacitated.

Normally, within our rules of engagement we begin with the most effective technique that the situational circumstances allow but in some cases, as with a grab or choke hold, a finger dislocation may need to be employed before a more effective technique can be executed.

As mentioned above some martial arts instructors teach intricate and complex finger dislocation techniques but the most effective way to dislocate and separate the metacarpal bones is to combine three movements; pull, twist, and bend.

1. 2. 3. Pull - traction the finger. Twist - torque, turn or rotate the finger. Bend - hyperextend the finger to its separation point.

We find in our classes that our students learn these three finger attack manipulations faster than complex finger locks. They just must remember; pull, twist, and bend. The analogy that we use is removing a turkey leg from a roasted turkey on Thanksgiving Day. To separate the leg from the carcass you will naturally pull, twist, and bend the leg and the soft tissue structures, ligaments, tendons, and joint cartilage will separate and tear apart.

Demonstration of finger dislocation with the 3 techniques of pull, twist, and bend. Also demonstrated is stepping directly on the attacker’s foot to limit movement and their balance. I have placed my elbow into the attacker’s throat.

I do not ascribe or recommend a cookbook approach to fighting techniques. Every attack is unique and may be completely unexpected. As they say, “Everyone has a plan until they are punched in the face”. Rather, the martial artist should be so well trained and comfortable in their art that they are capable of moving with creative, spontaneous, and instantaneous attacks and attack counters without thought.

Photograph Dislocated finger, 5th Metacarpal Source: Mdumont01 / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) 62

Conclusion:

The object of this 3-part series of articles has been to investigate the medical implications of authentic Tai Chi Chuan utilized for combat purposes and as a realistic form of self-defense. It is a sad situation that contemporary Tai Chi Chuan has been stripped of much of its historical roots as a combat martial art and has been relegated as a metaphysical new age exercise and meditation practice. As a result of this inaccurate connotation Tai Chi Chuan has been discarded by many martial artists, fighters, and self- defense instructors as too esoteric and convoluted to have any practicality in serious combat, fighting, or self-defense situations.

I have an extensive personal library, collected over a period of more than 50 years, of books on Tai Chi Chuan. None of these books, many of them considered to be Tai Chi Chuan classics, contain the basic combat applications of Tai Chi Chuan that have been included in these articles. This observation is not intended to be a criticism. In the past it was simply not considered appropriate to transmit combat applications, often thought of by teachers of Tai Chi Chuan as ‘secret” information to only be shared with “inner door” students, in publications intended for the general population.

It is my hope that this brief series of articles on The Medical Implications of Combat Tai Chi Chuan Techniques, Investigating Blunt Force Trauma, has placed some light on authentic Tai Chi Chuan and its historical roots as a formidable martial art.

Photography Credit and Assistance:

Many thanks to the gifted and talented photographer Abass Ali for his excellent images and to Mohamed Jabateh who assisted this effort as my “attacker” and who endured no small amount of pain for his effort. Both Abass Ali and Mohamed Jabateh are talented and dedicated martial artists who, although in their teenage years, have trained with me for the past 8 years.

The author, in his 8th decade of life, (far right) with students Mohamed Jabateh (far left ) and Abass Ali (center)

About the author:

Dr. Gregory T. Lawton, D.C., D.N., D.Ac. is a chiropractor, naprapath, and acupuncturist. He is the founder of the Blue Heron Academy of Healing Arts and Sciences where he teaches biomedicine, medical manual therapy, and Asian medicine. Dr. Lawton is nationally board certified in radiology, physiotherapy, manual medicine, and acupuncture. He was the vice president of the Physical and Athletic Rehabilitation Center which provided physical therapy for professional athletes, Olympians, and victims of closed head and spinal cord injuries.

Since the early 1960s Dr. Gregory T. Lawton has studied and trained in Asian religion, philosophy and martial arts such as Aikido, Jujitsu, Hap Do Sool, Kenpo/kempo, and Tai Chi Chuan.

Dr. Lawton’s most noted Asian martial art instructor was Professor Huo Chi-Kwang who was a student of Yang Shao Hou.

References:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5. Chen Pan-Ling’s Original Tai Chi Chuan Textbook, Chen Pan Ling, Transliterated by Y.W. Chang, Translated by Y.W. Chang, and Ann Carruthers, Ed.D, Blitz Design, New Orleans, Louisiana, 1998, Copyright Y. W. Chang and Ann Carruthers

Shaolin Chin Na Fa: Art of Seizing and Grappling, by Liu Jin Sheng, Shan Wu, Shanghai, China, 1936 (Copyright Andrew Timofeevich 2005).

Tai-Chi Touchstones: Yang Family Secret Transmissions, Compiled and translated by Douglas Wile, Sweet Ch’i Press, Brooklyn, New York, Copyright 1983, Douglas Wile

T’ai Chi Classics, Waysun Liao, Shambhala Publications, Boston & London, 1977/1990, Copyright Waysun Liao

Trail Guide to the Body, Second Edition, Andrew Biel, Books of Discovery, Boulder, Colorado, 1997/2001, Copyright Andrew Biel