6 minute read

Looking Back at the 12 Deadly Katas Peter Jones

from Lift Hands Volume 20 December 2021 - The Multi-Award Winning Martial Arts Magazine

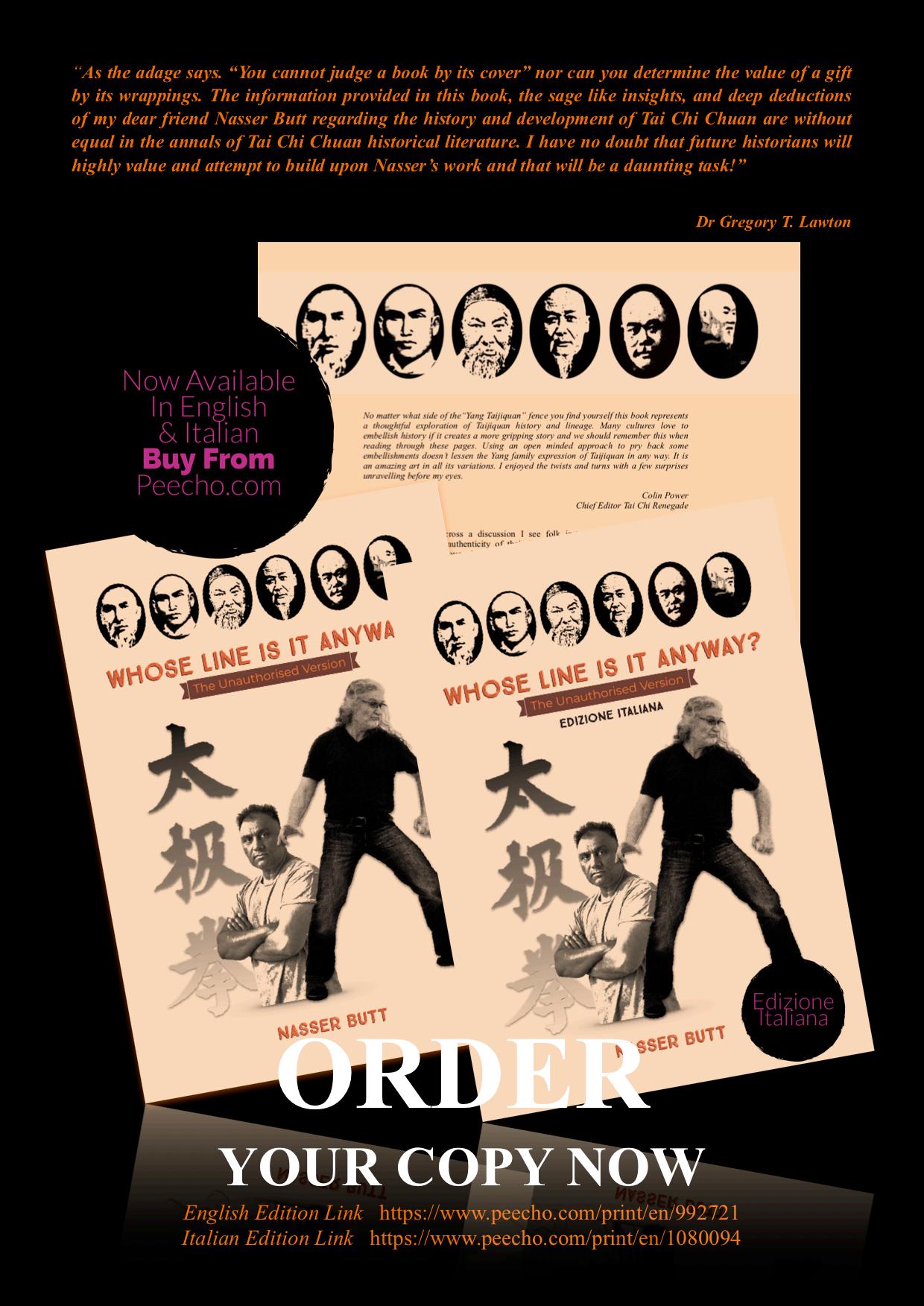

by Nasser Butt

“The way to win in battle is to know the rhythms of particular opponents and use beats that your opponents do not expect, providing formless rhythms from rhythms of wisdom.”

Miyamoto Musashi

“As the water shapes itself to the vessel that contains it, so a wise man adapts himself to circumstances.” Confucius

“My opponent dictates how they get hit”

Nasser Butt

Any traditional martial art worth their salt have forms, solo ‘patterns’ or kata, and training methods, two person drills that we practice to test our form using the resistance of a second person. There are some in the martial arts world that say that forms are useless, and that all we need are training methods. After all you are only going to be fighting people, what's the use of a movement without a specific technique? If you can’t use it in a fight, then what's the use of the movement?

With the increase in popularity of sport based martial arts, the traditional forms are seen to be more and more useless by the majority of modern practitioners, unless the technique can be adapted immediately. I remember when I thought the same during my early years of martial arts. Every sparring session and competition I went to was constantly fuelled by the need to have, ‘a tool for every situation,’ and in some respects it worked, as long as I was faster and or stronger.

It was only after I came out of sport oriented, weight class-controlled matches that I realised that in the area of self-defence, I was more than likely to be outmatched in both strength and speed or at least one or the other. I felt the only way to even the odds would be to know more and more techniques to cover every eventuality. I would play out scenarios in my head always saying if this happened I would respond in this way. With this came fear, fear of trying to predict the opponents next move and when learning weapons, it was even worse. After all, even a foot and a half long piece of wood could cut your head open or kill you if well placed. Every class I went to left me trying to clear my body of the stress of controlled situations.

This was about the time where I started my journey in Tai Chi and the original Yang Lu Chan form. This form was unique in that it was termed an “abstract” form. Abstract forms change the emphasis of our movement from externally oriented i.e. do this in response to this, to an internally oriented focus. Importance is based on how to carry out a movement measured to your own body and how to achieve the movement in the most efficient manner. As Nasser always says, “If you don’t know where your own body is in space and time, good luck knowing where your opponent is.”

Regardless of what an opponent throws at you. Your arms can only move so high or low and that is dependent on the length of your arms and not your opponents. Our legs are only able to take us as far as they can step which dictates where you can go to avoid an incoming attack. I’m not saying that this isn’t how all forms and kata should have been taught, but it was the first time that measuring my movements against myself had been stressed in such a pragmatic manner.

This eventually led to the term of “rhythm” during fighting. It’s a term so important that Miyamoto Musashi deigned to include it in his seminal martial treatise, “The Book of Five Rings.” How does this apply to abstract forms? If we look at the definition of rhythm it is the “a regular, repeated pattern of sounds or movements” as per Merriam and Webster. Everything in life, be it a piece of music, to a conversation, when people start and stop speaking, to a physical confrontation has a rhythm. Every person has their own rhythm, some are slow and deliberate whilst others are quick and uneven. So, in terms of movement how do we discover our own physical rhythm? The most obvious physical way would be dancing but how would this apply with regard to martial movement?

It’s a simple but arduous process of working out what the optimal way is of moving for your body. When I say this, I am talking about the length of your limbs to your torso and the way the fascia connect to the bones dictate the unique way you move and the unique alignment that force is transmitted through your body. The prerequisite for this is to have abstract forms which teach you the way of moving that is best for you. For example, in the Tai Chi posture P’eng or ‘Ward Off’ the classical posture requires the left wrist to be on the centre line of the body, the left elbow over the left knee, and the left forearm to be slanted upwards to ensure that the force rides over the left arm which deflects the energy up and away from the centre. These points of reference are subject to your own body shape. Of course this isn’t just based on hours of practice, but the emphasis on movements first being measured within oneself before we measure the outer world. Only now do we really start to know our own rhythms, where our body likes to transmit force and along which lines.

I found that once I had started to know my own rhythm, I could do away with collecting a dictionary of technique, instead I was starting to simply react to what an opponent threw at me in the best way I could at that point in time. This isn’t to say that you miraculously stop making mistakes, that still happened (happens) many times as I improved my understanding of my own body, but what was gone was the severe stress associated with confrontation and the amount of time that it took to come down from that uncomfortable buzz.

We all know people who have no rhythm, they can’t hold a beat, always out of time with a piece of music. It’s as if they are trying to dictate their own rhythm on a situation that already has one. The only way to follow a rhythm is to surrender to it. Only then can you blend your own rhythm to the original one.

This is the same principle as in a confrontation. If know how I move in space and time and where my power sits in relation to myself, then and only then can I really read the rhythm of my attacker. Only then can I, as Confucius says, become like water and “shape myself to the vessel that contains it” and become wise and “adapt myself to the situation.”

The great thing is that the concept of an abstract form is just that, a concept. It’s nothing that can’t be laid over any existing forms. All it requires is to look within before adapting movements to the outside world.