13 minute read

PUBLIC SAFETY AND VIOLENCE PREVENTION

The Community Care and Justice Initiative

by Juan Rios, DSW, LCSW

In the face of heightened divisiveness within the country at large, the South Orange Village Center Alliance, in 2017, emblazoned the town’s streets with banners proclaiming a simple yet telling message: “Everybody Belongs Here.”

Committed to embodying that message—which extends from a long and storied tradition of diversity, intentional integration, and public service within South Orange—in 2021, South Orange Village created the Community Care & Justice Initiative (CC&J). Headed by Village Trustee and Chair of the Health and Public Safety Committee, Donna Coallier and Dr. Juan Rios, Director of the Seton Hall University Masters of Social Work program, CC&J takes a health and wellness approach to public safety by cultivating respect, compassion, and justice as the centerpiece of the community ecosystem. These core social work values are embedded into every systemic component of this initiative.

CC&J is delivered and financed through the South Orange Police Department. Currently, this department and its cohorts lack access to state-of-the art—or even adequate—training on mental health awareness, de-escalation techniques, implicit and explicit bias, and restorative/transformative justice practices. As a result, the police department and rescue squad have an outsized impact on community mental health and wellness without the needed investment in training, schooling, and credentialing to appropriately steward this impact.

To date, the financial cost of emergency mental health crisis engagements in our community has fallen primarily on the police department and rescue squads, whose budgets have sparse room for mental health and wellness training—deemed “extra” according to the currently outdated law enforcement and emergency medical curriculum.

The Community Care & Justice solution envisions a more proactive, preventative, and collective approach to mental health and wellness. CC&J engages the whole community, as well as establishes a partnership with first responders and newly hired social work professionals. This model is a framework that engages community-wide research on values, assets and needs, then utilizes the data to inform strategic interventions that fit the respective community. CC&J also establishes continued assessment/ evaluations from University researchers to track its outcomes and ensure the efficacy for replication.

The mission of Community Care & Justice is to build a care and compassion platform that seeks to engage South Orange community members in designing and traveling their own wellness journeys,

with a particular focus on protecting and elevating the community’s most vulnerable members and its youth. Community is broadly defined by South Orange Township as: “people who live, work, attend college, or own businesses [in South Orange] as well as their visitors and patrons, and our neighbors in bordering municipalities.”

CC&J Program goals include the following:

• To better serve our entire community through public health outreach with particular care for our youth and others who can benefit from social work and restorative justice, and/or experience bias or racial inequities, crime, bullying, homelessness, substance misuse, in-home violence, mental health crises, etc.

• To further enhance South Orange Police

Department’s cultural improvements already underway and permanently embed care and compassion service values into department operational strategy, protocol, and day to day interactions.

• To develop best practices that are data driven and scalable so they can be replicated across other

Essex County communities and beyond.

CC&J is unique because South Orange Township is a small municipality. As such, we were able to garner support at all levels of government (elected officials, police and health departments, municipal administration) to quickly deliver change with minimal bureaucracy. Many larger municipalities have similar reform efforts underway, but none involve all levels of government and most are looking at much different problem sets. Furthermore, in the state of New Jersey, close to 80% of our municipalities are small in scale with similar demographics and problems as those we face in South Orange—so there is tremendous potential to scale our solution here in New Jersey and beyond.

It is our hope CC&J will be a model that social workers across the state and country can bring to their communities by first recognizing that there is no “one size fits all” model to community wellness and prevention. It begins by engaging the community members first and allowing them to have a decision on how they design the future they would like to live in. Our social work values of human dignity, social justice, service, and importance of human relationships are transferable values that should be embedded into community movements and governmental initiatives designed to address what peace and transformative justice work looks like in our respective communities.

Aboutthe Author:

Dr. Juan A. Rios is an Assistant Professor at Seton Hall University Master of Social Work program. He is presently on a research sabbatical partnering with the Township of South Orange Township on reimagining public safety. His research interests include integrating care and compassion into societal and pedagogical structures through transformative/ caring justice frameworks.

Bloomfield Township: A New Model for Human Service and Law Enforcement Collaboration

by Karen Lore, LCSW and Paula Peikes, LCSW

The Department of Human Services in Bloomfield Township works to develop programs that address the needs of poor and working-class residents in the town. Working together we have networked with faithbased organizations and community leaders and successfully collaborated to better coordinate and deliver services to residents in our town of more than 47,000.

In the wake of the tragic death of George Floyd and other incidences of police violence against persons of color, Bloomfield township has taken multiple steps to address the safety of all residents and to ensure fairness and accountability in encounters between law enforcement and residents of color. In the past year, the township held multiple community conversations on race and police violence and adopted seven of the eight policies outlined in the “8 Can’t Wait Campaign” to decrease the possibility of police violence. The police department has also implemented new training procedures that include recognizing implicit biases and de-escalation. These trainings are mandatory for all officers.

Township police have also taken steps to address those cases where police are called repeatedly to address social issues and disturbances—cases where a typical law enforcement response may not be the best way to handle the needs of the residents involved. The problem is multi-faceted and compounded by the many social issues impacting residents who more frequently interact with law enforcement. Recognizing, this need, police have sought to formalize a relationship with our Human Services division to offer social work support to officers in the field. The intent of this partnership is to have social workers immediately involved when police are dispatched in response to mental health/ family/domestic/elderly issues and other behavioral/ social issues that may require more of a specialized social work response.

To launch this initiative, our town convened a task force comprised of key executive staff, council members, and the mayor; also included were the police and health director and lead social workers from our Human Services division. Our in-house staff of clinical social workers were uniquely positioned and qualified to provide valuable input on the complex needs of residents. In our discussions, the task force considered programs implemented in other communities both locally and on a national level, but we ultimately determined to tailor our program based on internal resources and experience in the field.

The law enforcement and human/social work collaborative program that has emerged from the work of the task force is based on past cases, collaborations, and working relationship we have built with the police in Bloomfield over the past 30+ years. While there are many models of policehuman/social services collaboration, what makes our model unique is that we are working from within, building on current resources and programs, rather than contracting out or having a non-profit entity take the lead. This is a critical difference and one that benefits us tremendously by formalizing a direct relationship between township social workers, governing body, and police, thus providing ready access to municipal resources, programs, and services at every level.

Community-based social work and practice are at the heart of this work. The ultimate intent of this new program is to reduce recidivism, reduce police intervention in non-violent calls, appropriately address the needs of residents in distress through established social work practices, and improve relationships between police and the community. In this model, social workers will be on-site and available to the police from 8:30am to 12 midnight Mondays - Fridays to co-respond with police on certain calls. Social workers will be available on-call from midnight to 8:30am and on weekends in case their services are needed.

The role of the social workers stationed in the police department will be to provide crisis intervention and assessment services and to advise the police when the call is better suited for a social work intervention. The larger task of the social workers will be to follow-up after each incident. Case management, community linkage, coordination with family members, and education will be critical in producing successful outcomes for the residents involved.

We are currently looking into grants and other potential funding sources to help extend the scope and reach of this initiative. The program is expected to launch within the next 6 months. We are currently recruiting for BSW and MSW level social workers. You can find our job posting on the NASW-NJ Job Center or view the announcement here.

Aboutthe Author:

Karen Lore, LCSW has been with the Bloomfield Division of Human Services since 1988. She currently serves as the Director of Health and Human Services and previously served as the clinical Director of the division’s outpatient mental health program. She is a member of the National Association of Social Workers, a licensed clinical social worker in NJ and obtained Diplomate status in the field of Social work in 1993 for her advanced clinical practice and expertise.

Paula Peikes, LCSW, has been employed with the Township of Bloomfield since 2000. She began her career in the town as a social work intern and was recently promoted to Director of Social Work. Paula is a licensed clinical social worker in NJ and has advanced certification in Family Therapy and training in EMDR. She also chairs the Bloomfield Municipal Alliance. For more information on Bloomfield Human Services or to contact Paula, visit www. bloomfieldtwpnj.com/217/Human-Services

Creating Trauma in the Name of Preparation: The Reality of School Lockdown Drills

by Nancy Kislin, LCSW, MFT

Students across our nation have come of age in a time when the basic assumption, “I will be safe in school,” no longer holds true. With the proliferation of the internet and the 24-hour news cycle, students learn about the latest mass shooting in real time. They go to school with the constant fear of being shot to death. On top of that, they must now cope with security drills in school, known as “lockdown drills”—active shooter and evacuation drills designed to prepare students for these horrific occurrences.

Every day in America, schools conduct security, or "lockdown,” exercises to combat and prepare for the threat of violence. Forty-two states, including New Jersey, mandate once-a-month lockdown drills, in addition to the 10 fire drills that are required. These exercises, designed to simulate active-shooter situations, are often not announced as drills and are conducted without warning. Although intended and designed to protect and prepare children, the real- world impact of this practice is highly damaging to the very students it is meant to protect.

Research reveals kids are showing signs of severe stress and trauma as an unintended consequence of these lockdown exercises. In research for my book on active shooter drills in schools, I interviewed hundreds of students and parents to study the impact of these drills and educate parents about their children’s experiences. I learned many children were feeling anxious about school safety, not just from potential active shooters, but also from the drills designed to prepare them for these situations. For instance, many reported worrying about going to the bathroom during the school day for fear of a lockdown event taking place while they’re on the way to, or in, the bathroom. Some openly discussed whether jumping out a second story window was a safer option than being trapped with a shooter in the school.

My research concludes that the very lockdown drills designed to secure a school and protect students are actually producing anxiety, stress, and trauma in participating students and staff. These drills simulate chaos and create fear, but do nothing to instill resilience in kids. We must redesign these drills so they instill skills and awareness in participants, rather than simply focus on the performative component of mimicking an active shooter situation.

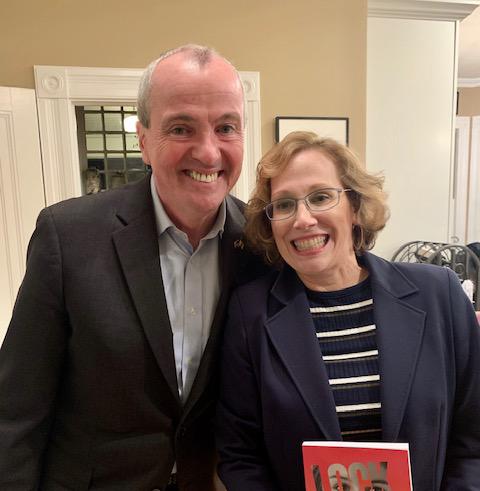

On April 15, Governor Murphy proposed authorizing the NJ Department of Education to establish trauma-informed and age-appropriate standards for lockdown drills, including encouraging preparation over simulation, barring use of simulated gunshots, providing advanced notice to parents about planned drills, duration limits, and training, and prohibiting rewarding children for fighting off potential gunmen during a drill. I say “BRAVO, Governor Murphy” for taking these bold steps to protect the mental, emotional, and physical health of all children in our state.

Following the Governor’s announcement, I contacted several of the young people I originally interviewed for my book, in search of their thoughts and reactions. One 17-year-old, told me, “this is a very good thing. It is common sense to just let us kids know it is a drill.” She continued:

I am angry about a lockdown that occurred a few months ago. My friends and I were walking back from Gym class when a teacher yelled for us to come hide in her closet. She told us to lock the door and barricade ourselves in. Then she left. Thankfully, it turned out to be a drill. You know, I wouldn’t have cried so hard and had nightmares if I had known it was a drill. My school didn’t realize how upset we were. They acted like it was no big deal. But I thought I was going to die.

My research, as well as recent statements by the Governor, should encourage action to ensure staff are trained to teach children strategies of self-care and resilience while addressing potential active shooter situations. Moreover, both teachers and students would benefit from extended processing time following these drills, rather than having to resume class the minute the “all clear” is sounded—a practice I refer to as the “double assault” on children. First, we traumatize kids through unannounced active shooter drills, then we act as if it was completely normal to pretend to be hiding from a violent killer. Nothing about that situation—drill or otherwise— is normal. By acknowledging the stress created by these school safety drills, we can validate students’ feelings in the moment, so they know others are struggling with fear and anxiety in the wake of these drills, rather than leaving them to experience these emotions alone and in silence.

Aboutthe Author:

Nancy Kislin, LCSW, MFT, is a New Jersey native, mother, child and adolescent psychotherapist, trauma researcher and author of the book “LOCKDOWN: Talking to Your Kids About School Violence.” She maintains a child and adolescent psychotherapy practice in Central N.J. Learn more at https://nancyjkislin.com