5 minute read

Up in Arms: Weaponizing Anger & Taking Action

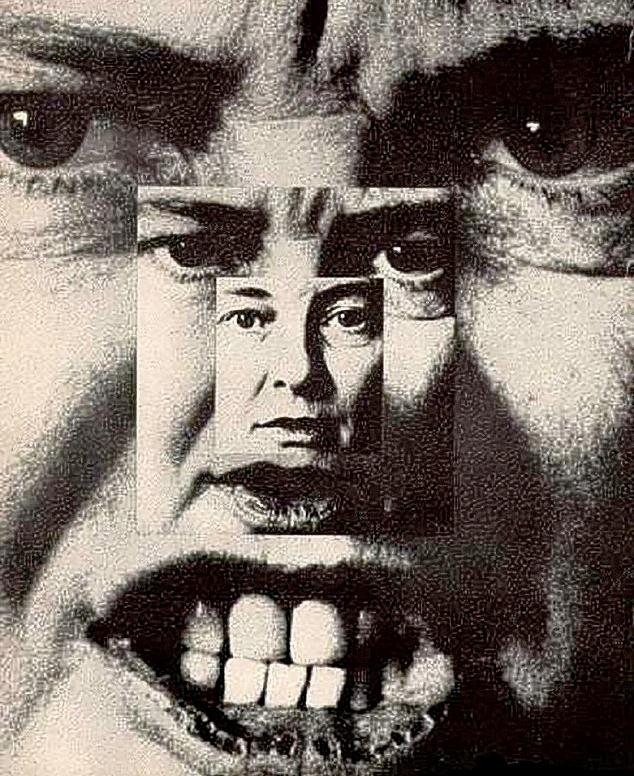

Punk is often defined by its conventionally masculine elements—the speed, anger, and aggression of its sound and look alike—and doing so keeps the narrative centered on white males. But it is not that women and/ or people of color do not experience this same rage, it is only that they are not allowed to express it. Violence enacted and anger articulated by white men is more socially acceptable than that of women and people of color. Even rape is normalized as an outlet for male libido and aggression, and the conviction that “boys will be boys” epitomizes this casual cultural mainstreaming of fundamentally anti-social behaviors. White men who act violently are positioned alternately as victims of consumer culture, of the country’s mental health crisis, of their bad mothers, of social isolation. Think Tyler Durden and Patrick Bateman, think Ed Gein and Norman Bates, think of the mass shooter profile. Meanwhile, angry and alienated Black men are deemed wild animals or diagnosed with a racial urban pathology, Black women are reduced to and dismissed as stereotypes, Asian women are limited by orientalist notions of natural subservience and politeness. For all women, anger is not lady-like, it is unbecoming, it is unhinged. And while the mainstream story of punk likes to focus on its white male artists, the subculture does create a space for these marginalized communities to sublimate a righteous rage.

The longstanding tradition of gender-relations dictates that men do things while women have things done to them. And for a woman to be angry or take action is to violate her role as passive object in this power dynamic. In her examination of the raperevenge plot of stories like The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, Johanna Schorn argues that the “common thread” between fictional and media representations of sexual violence is “the passive role it relegates women to.” She posits that women “are passive victims of the violence that is enacted on their bodies, first through the actual rape, and second through the mechanisms of a rape culture that generates responses (from disbelief to vilifications).” What’s notable in Schorn’s argument is her equation of the immediate physical violence of sexual assault with the rhetorical violence that follows. To silence—by censoring or discrediting—victims of violence is to both perpetuate the myth of submission that underpins a rape culture and further divest women of their autonomy. If we (and we should) see sexual violence as a microcosm of structural oppression, then we can understand retaliation against individual perpetrators as retributive justice.

Advertisement

And so the story goes that men are pushed toward aggression by a regrettable confluence of genetics and social factors, and they can thus be positioned as the real victims of their own violence; women and particularly women of color, on the other hand, possess every right to be angry, yet they are still pushed into silence and inaction. Radical militant feminism posits a solution to this cultural narrative.

When those in power continue to enact violence against the exploited classes, violence becomes a legitimate, if not necessary, means of resistance for those in the margins.

In 1981, writer and activist Audre Lorde delivered the keynote speech at the National Women’s Studies Association Conference. Her presentation, “The Uses Of Anger: Women Responding To Racism,” offers a blistering response to the racism within the circles of white feminism. “Every woman has a well-stocked arsenal of anger potentially useful against those oppressions, personal and institutional, which brought that anger into being,” Lorde urges, “Focused with precision it can become a powerful source of energy serving progress and change.”

It is crucial then that anger does not remain in the narrow purview of white men. Anger can translate to reckless destruction and violence, but it can also be a “precis[e]” tool for the dismantling of oppressive structures—a weapon against the structural violence that breeds it.

Punk is often violent in its lyrics and at its live shows, but the fed-up women of the scene suggest violence not as an expression of generalized angst, but as a justified weapon against their oppressors. On their 1988 Track “Ms. 45,” L7 tells of an unnamed woman who “walks the streets at night / And they think she is a whore.” The rationale for the harassed woman is simple: “You fuck with her / She’ll blow your ass away.” We see a similar sentiment on 7 Year Bitch’s “Dead Men Don’t Rape” and Heavens to Betsy’s “Terrorist.” Both tracks threaten graphic violence from shooting to gutting and eye gouging, and both tracks construct rage-driven fantasies of female revenge. The violence here is anything but bratty—an epithet frequently applied to punk acts; it is graphic, brutal, and angry, but, above all, it is justified. These stories of retribution function as outlets for female emotion that is otherwise not allowed to be expressed, and they work as tools for reshaping a modern feminist consciousness.

In the wake of #MeToo and Time’s Up, the prevalence of sexual violence and harassment is much clearer to contemporary audiences than it was to those in the 80s and 90s. But mere acknowledgment on the cultural periphery does not translate to action. One 1984–1985 survey of women in college found that 42% of rape victims told absolutely no one about the assault; another survey in 2018 revealed that 2.6% of sexual assault victims reported it to the police. While feminist movements of the 20th century, including Riot Grrrl, focused national attention on the rampancy of sexual violence in the country, 21st century women are still faced with an inadequate criminal-justice system and a horrifyingly cavalier public attitude.

Material Support’s 2019 EP Specter clocks in at just over 10 minutes, but every second of it is bursting with the fury of its age. Driven by a revolutionary Marxist vision for the total transformation of American society, the album attacks the failing institutions of criminal-justice, healthcare, education, and welfare, to name a few. On “Me Too,” they confront institutions of sexual violence. Though the majority of the track assumes the point of view of a sexual predator, the final lines return the power to the would-be victim: “I could end you / Send you to your grave! / I could end you / So you better behave!”

And so the story ought to go that women deserve justice. And when the bureaucratic channels of “justice” are ineffective and those with power only continue to wield violence as a weapon of oppression, then women have no choice but to abandon nonviolence and the status quo it reinforces.