NATIONAL CONCERT HALL 2024 — 2025 SEASON

NATIONAL CONCERT HALL 2024 — 2025 SEASON

mezzo-soprano

FRIDAY 1 NOVEMBER 2024, 7.30 pm

National Symphony Orchestra

Laurence Cummings conductor & harpsichord

Programme: Haydn, Martínez, Mozart

MONDAY 10-FRIDAY 14 FEBRUARY 2025

Celebrating the Voice

Professional Development Programme for Singers & Recital and Orchestra performances

THURSDAY 1 MAY 2025, 7.30 pm

National Symphony Orchestra

Clelia Cafiero conductor

Programme: Mozart, Donizetti, Puccini, Bellini, Rossini

Book now on nch.ie

Tickets from €15

National Symphony Orchestra

Mihhail Gerts conductor

Dame Sarah Connolly mezzo-soprano

Friday 13 September 2024, 7.30pm

National Concert Hall

Presented by Paul Herriot, RTÉ lyric fm Programme

Dvorˇák In Nature’s Realm / 12’

Alma Mahler Six Songs (arr. Colin and David Matthews) / 20’

‘Die stille Stadt’ (3’)

‘Laue Sommernacht’ (3’)

‘Licht in der Nacht’ (3’)

‘Waldseligkeit’ (3’)

‘In meines Vaters Garten’ (4’)

‘Bei dir ist es traut’ (4’)

Mahler

Symphony No. 1, ‘Titan’ / 53’

Broadcast live on RTÉ lyric Live on RTÉ lyric fm

PLEASE NOTE: The NCH does not permit photography or videography during the performance (without prior permission). We kindly ask you to refrain from using any recording equipment for the duration of tonight’s performance.

NCH Board Members

Maura McGrath Chair | James Cavanagh | Cliona Doris

Rebecca Gageby | Hilary Hough | Peter McKenna

Niamh Murray | Michelle O’Sullivan | Don Thornhill

Patron

Michael D. Higgins President of Ireland

Welcome to the opening concert of the National Symphony Orchestra’s Season, proudly taking its place for the first time as part of the National Concert Hall’s 2024-2025 Season.

The NSO Season Opening is one we approach with excitement and anticipation: it marks the orchestra’s return following its summer break; our return, as audiences, to the richness of the symphonic and choral repertoire; and it signals the many months to come of music-making and collaborations with exciting guest artists, conductors and composers, committed partner promoters, and Irish and international music organisations and broadcasters.

This evening’s concert is a double pleasure: for the works being performed and for two fine artists: Mihhail Gerts, making a welcome return, and Dame Sarah Connolly, the acclaimed mezzo-soprano.

This new season is enticing in so many ways: the Friday night concerts; seasonal celebrations; family and schools events; concerts in Galway, Limerick, Wexford and Waterford; the exploration of diverse repertoire with our Artists-in-Residence, Bryce Dessner, Tara Erraught and Jessie Grimes; and the development programmes for emerging composers and young singers.

Interwoven throughout are Irish and world premieres, big choral works and anniversary celebrations around Puccini, Bruckner, Johann Strauss II, Shostakovich and Ravel.

Particular thanks to the Department of Tourism, Arts, Gaeltacht, Heritage, Sport and Media, to RTÉ and RTÉ lyric fm, our corporate supporters, Friends, Season Friends and Patrons, and to the orchestral players and our own staff, who, together, make all this possible.

We make music to share it. We look forward to sharing the exciting and rewarding year ahead with you.

Robert Read CEO

Maura McGrath Chairperson

It is both an honour and a joy for me to open the new concert season of the National Symphony Orchestra, together with Dame Sarah Connolly, in this beautiful programme, giving Gustav Mahler, the ‘Titan’ of the symphonic genre, a place next to compositions by his muse Alma Mahler.

‘What have I done? These songs are good, they are excellent. God I was narrow-minded those days.’ Such was Gustav Mahler’s reaction when turning his attention to the songs of Alma Mahler in his final year of life. He had forbidden her to compose when they married.

Gustav and Alma had one of the most controversial relationships in the 20th century, but they certainly loved being ‘In Nature’s Realm’ and spent some of their most harmonious moments there. This masterly overture by Antonín Dvorˇák radiates the calmness, happiness and excitement of being surrounded by beautiful landscapes.

Having had the privilege of conducting in the National Concert Hall many times, I always look forward to performing here together with the wonderful musicians of the National Symphony Orchestra, sharing our passion and love for music with you, our audience, and with guests from abroad.

Mihhail Gerts

Antonín Dvorˇák (1841-1904)

In

Nature’s

Realm

As he approached his 50th birthday, in the Spring of 1841 Dvorˇák began to plan a set of interlinked concert overtures portraying ‘three great creative impulses of the Universe – Nature, Life, and Love’ that would be performed together.

A change of mind saw him re-casting the intended trilogy as separate pieces, giving each an individual opus number. Even so, the original thematic notion still loosely applies: Nature represented by the first of the overtures, In Nature’s Realm (Op. 91); Life by Carnival (Op. 92), and Love, albeit of the corruptible variety, by Othello (Op. 93). Threaded through all three was a melody evoking ‘the unchangeable laws of Nature’.

Dvorˇák’s attachment to the natural world was a permanent feature of his music and it finds effusive voice in In Nature’s Realm : a veritable hymn to Vysoká, the secluded summer residence he had bought some 50 kilometres south-west of Prague, and to the idyllic Bohemian countryside he adored. Certainly it is filled with a sense of bucolic delight and pastoral contentment. While composing it, Dvorˇák had a vivid image of it as representing ‘the emotions awakened in a solitary walk through meadows and woods on a quiet summer afternoon, when the shadows grow longer until they lose themselves in the dusk and gradually turn into the early shades of night’.

It begins with the tentative first steps of a serene melody in bassoons and violas that seems to hold its breath as the scene begins to fill with the birdsong of flute and oboe. The central ‘nature’ motif asserts itself in a blaze of euphoric sunshine, its repetitions in various instruments and different registers mimicking the halekacˇka , a Moravian yodelling song.

Strings introduce a new, markedly more poetic theme, the sensations and perfume of nature inked effusively in by the full orchestra before it and the nature theme pirouette around each other with a delirious delight in their surroundings.

A blaze of horns and trumpets echo the nature theme with an ecstatic fervour that quickly dies away as lengthening shadows cast the scene into crepuscular hues. As dusk mediates between the fading day and the encroaching night, the birdsong so prevalent throughout is noticeable now by its absence, one late, twilit scurry of blackbirds and a lone cuckoo serving as a last hurrah for the Eden just experienced. As night falls, nature begins to sleep and silence ensues.

‘Die stille Stadt’

‘Laue Sommernacht’

‘Licht in der Nacht’

‘Waldseligkeit’

‘In meines Vaters Garten’

‘Bei dir ist es traut’

That Alma Schindler found herself at the centre of the artistic world in early-20th century Europe was due in no small part to the advantage afforded by her being the daughter of the well-connected landscape painter Emil Schindler, whose circle of acquaintances included Gustav Klimt, who was enamoured enough to make several portraits of her. But Alma’s own assertive independence of mind and self-possession – strikingly modern qualities for the time – allied to her skill as a composer set her apart.

From early on, Alma was her own woman. She fashioned her life fully cognisant of her talent as a composer and equally aware of the effect her beauty had on a succession of male admirers. She met Gustav Mahler while studying composition with Alexander von Zemlinksy, with whom she had an intimate relationship. It didn’t prevent her from entering into a clandestine affair with Mahler, 19 years her senior, whom she married in 1902.

In an infamous letter to her during their courtship, Mahler insisted that Alma should forsake music to devote herself to him. A demand she readily acceded only to later regret her acquiescence and complain ‘I’ve sunk to the level of a housekeeper!’

Incidentally, the American songwriter Tom Lehrer wrote a satirical ballad, Alma , about her varied love life, the passage dealing with Mahler quipping: ‘Their marriage, however, was murder / He’d scream to the heavens above / “I’m writing Das Lied von der Erde / and she only vants to make love!”’.

After discovering her affair with the architect Walter Gropius in 1910, Mahler contritely began to encourage Alma to compose again, editing and helping to publish some of her songs. Following Mahler’s death in May the following year, Alma went on to have an affair with the artist Oskar Kokoschka before marrying Gropius. That relationship was also destined to falter and to end in divorce after she bore a child by the novelist and playwright Franz Werfel, who became her third husband.

It’s not known how many songs Alma composed. A mere 17 have survived. Tonight, four of the Five Songs published in 1911 frame two from the Four Songs published 1915, although all date from 1900-01 when Alma was in her early twenties.

‘Die stille Stadt’ (The Silent Town) sets a text by Richard Dehmel and adroitly incorporates Wagner’s famously evocative Tristan chord – a telling borrowing that hints at the passion that lies beneath its surface mingling of sinister forebodings and fear that are eventually resolved in the consoling ‘song of praise’ heralded by children’s voices.

From the same 1911 collection, ‘Laue Sommernacht’, with lyrics by the now all but forgotten Otto Julius Bierbaum, is distinguished by passionate harmonies and regarded by many as her finest song. It is a sensual paean to the sylvan delights of the ‘Mild Summer Night’ its title hymns.

Bierbaum also provided the text for ‘Licht in der Nacht’ (Light in the Night), the first of the 1915 Four Songs compendium. Dark-hued lyrics contemplating the flickering light of a lone star in the night sky prompt a haunting, chromaticallyaccented accompaniment of ravishing Romantic fervour.

Also from that set, and again setting Richard Dehmel, ‘Waldseligkeit’ (Bliss in the Woods) is no less lustrous, as befits a song that shifts between reflective repose and moments of rapturous passion.

Better remembered today as a translator (notably of Pierrot lunaire, which Schoenberg later set), Erich Otto Hartleben’s ‘In meines Vaters Garten’ (In My

Father’s Garden), the longest of tonight’s songs, casts romance as fantasy. Fond, loving memories of her father intermingle with the stirrings of her new attraction to Gustav Mahler, the music appropriately alternating between warmth and passion.

With a text by Rainer Maria Rilke, ‘Bei dir ist es traut’ (I am at ease with you) is one of Alma’s most exquisite and beautiful songs. And one of her most intimate, the singer quietly relishing a moment of stilled time with her beloved. As night and nature eavesdrop on the lovers, she beseeches ‘Let us stay quiet, So no one knows of us!’.

Alma Mahler: Six Songs

Die stille Stadt (Richard Dehmel, 1863-1920)

Liegt eine Stadt im Tale, ein blasser Tag vergeht, es wird nicht lang mehr dauern, bis weder Mond noch Sterne nur Nacht am Himmel steht.

Von allen Bergen drücken

Nebel auf die Stadt, es dringt kein Dach, noch Hof noch Haus, kein Laut aus ihrem Rauch heraus, kaum Türme noch und Brükken.

doch als dem Wandrer graute, da ging ein Lichtlein auf im Grund und aus den Rauch und Nebel begann ein Lobgesang aus Kindermund.

The Silent Town (Richard Dehmel, 1863-1920)

A town lies in the valley, a pallid day fades; it will not be long now before neither moon nor stars but only night will be seen in the sky.

From all the mountains fog presses down upon the town; no roof may be discerned, no yard nor house, no sound penetrates through the smoke, barely even a tower or a bridge.

But as the traveller became filled with dread a little light shone out; and from out of the smoke and fog a song of praise began, sung by children.

Translation © Sharon Krebs

Laue Sommernacht

(Otto Julius Bierbaum, 1865-1910)

Laue Sommernacht: am Himmel

Stand kein Stern, im weiten Walde suchten wir uns tief im Dunkel, und wir fanden uns.

Fanden uns im weiten Walde

In der Nacht, der sternenlosen, hielten staunend uns im Arme

In der dunklen Nacht.

War nicht unser ganzes Leben nur ein Tappen, nur ein Suchen, da in seine Finsternisse, Liebe, fiel dein Licht.

Licht in der Nacht

(Otto Julius Bierbaum, 1865-1910)

Ringsum dunkle Nacht, hüllt in Schwarz mich ein, zage flimmert gelb fern her ein Stern! Ist mir wie ein Trost, eine Stimme still, die dein Herz aufruft, das verzagen will.

Kleines gelbes Licht, bist mir wie der Stern überm Hause einst Jesu Christ, des Herrn und da löscht es aus. Und die Nacht wird schwer!

Schlafe Herz. Schlafe Herz. Du hörst keine Stimme mehr.

Mild Summer Night (Otto Julius Bierbaum, 1865-1910)

Mild summer night, in the sky

There are no stars; in the wide woods

We searched deep in the darkness And we found ourselves.

We found ourselves in the wide woods, In the night, the starless night; We held ourselves in wonder in each other’s arms

In the dark night.

Was not our entire life

Simply groping, simply searching? There, into its darkness

Tumbled your light, Love.

Translation © Emily Ezust

Light in the Night (Otto Julius Bierbaum, 1865-1910)

Dark night all around, enveloping me in black, Timidly a star flickers yellow from afar! It’s to me like a comfort, a quiet voice, Which calls on your heart that wants to give up.

Little yellow light, you are like a star to me

Above the house of Jesus Christ the Lord, once, And there it goes out! And the night turns heavy!

Sleep, my heart! You hear no voice any more!

Translation © Elisabeth Siekhaus

Waldseligkeit

(Richard Dehmel, 1863-1920)

Der Wald beginnt zu rauschen, den Bäumen naht die Nacht, als ob sie selig lauschen, berühren sie sich sacht.

Und unter ihren Zweigen, da bin ich ganz allein, da bin ich ganz mein eigen, ganz nur Dein!

In meines Vaters Garten

(Otto Erich Hartleben, 1864-1905)

In meines Vaters Garten

Blühe, mein Herz, blüh’ auf in meines Vaters Garten stand ein schattender Apfelbaum süsser Traum, stand ein schattender Apfelbaum.

Drei blonde Königstöchter

Blühe, mein Herz, blüh’ auf drei wunderschöne Mädchen schliefen unter dem Apfelbaum süsser Traum, schliefen unter dem Apfelbaum.

Die allerjüngste Feine blühe mein Herz, blüh auf die allerjüngste Feine blinzelte und erwachte kaum Süsser Traum blinzelte und erwachte kaum.

Bliss in the Woods (Richard Dehmel, 1863-1920)

The woods begin to rustle

And Night approaches the trees, As if it were listening happily For the right moment to caress them.

And under their branches

I am entirely alone I am entirely myself, Entirely yours!

Translation © Emily Ezust

In My Father’s Garden (Otto Erich Hartleben, 1864-1905)

In my father’s garden

Bloom, my heart, bloom forth!

In my father’s garden

Stands a leafy apple tree

Sweet dream

Stands a leafy apple tree.

Three blonde King’s daughters

Bloom, my heart, bloom forth

Three wondrous maidens

Slept under the apple tree

Sweet dream

Slept under the apple tree.

The youngest of the fine ladies

Bloom, my heart, bloom forth! The youngest of the fine ladies

Blinked but did not awake.

Sweet dream.

Blinked but did not awake.

Die Zweite fuhr sich übers Haar blühe mein Herz, blüh’ auf sah den roten Morgensaum süsser Traum!

Sie sprach: Hört ihr die Trommel nicht? blühe mein Herz, blüh’ auf! süsser Traum hell durch den dämmernden Raum?

Mein Liebster zieht in den Kampf blühe, mein Herz, blüh’ auf.

Mein Liebster zieht in den Kampf hinaus, küsst mir als Sieger des Kleides Saum süsser Traum, küsst mir des Kleides Saum!

Die Dritte sprach und sprach so leis blühe mein Herz, blüh’ auf!

Die Dritte sprach und sprach so leis: Ich küsse dem Liebsten des Kleides Saum süsser Traum, ich küsse dem Liebsten des Kleides Saum.

In meines Vaters Garten blühe, mein Herz, blüh’ auf in meines Vaters Garten steht ein sonniger Apfelbaum süsser Traum steht ein sonniger Apfelbaum!

The second moved a hand over her hair Bloom, my heart, bloom forth!

Saw the morning’s hemline of red

Sweet dream

She spoke: Did you not hear the drum? Bloom, my heart, bloom forth!

Sweet dream

Clearly through the twilight space?

My beloved joins me on the battlefield Bloom, my heart, bloom forth

My beloved joins me on the battlefield, Kisses me as the victor on the hem of my uniform

Sweet dream

Kisses me as the victor on the hem of my uniform.

The third spoke – and spoke so softly Bloom, my heart, bloom forth!

The third spoke – and spoke so softly I kiss the hem of my beloved’s uniform.

Sweet dream

I kiss the hem of my beloved’s uniform.

In my father’s garden

Bloom, my heart, bloom forth!

In my father’s garden

Stands a leafy apple tree

Sweet dream

Stands a leafy apple tree.

Translation © Emily Ezust

Bei dir ist es traut (Rainer Maria Rilke, 1875-1926)

Bei dir ist es traut, zage Uhren schlagen wie aus alten Tagen, komm mir ein Liebes sagen, aber nur nicht laut!

Ein Tor geht irgendwo draussen im Blütentreiben, der Abend horcht an den Scheiben, Lass uns leise bleiben, keiner weiss uns so!

I am at ease with you (Rainer Maria Rilke, 1875-1926)

I am at ease with you, Faint clocks strike As from olden days, Come, tell your love to me, But not too loud!

Somewhere a gate moves Outside in the drifting blossoms, Evening listens in at the window panes, Let us stay quiet, So no one knows of us!

Translation © Knut W. Barde

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 1 in D major, ‘Titan’

I. Langsam, schleppend – Immer sehr gemächlich II. Kräftig bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell

III. Feierlich und gemessen, ohne zu schleppen IV. Stürmisch bewegt

Mahler’s First Symphony may have been composed under difficult circumstances and its premiere in Budapest in 1889 greeted with a decidedly lukewarm response, but for the 27-year-old composer it represented a sort of triumph. It was, he later declared, ‘the first work in which I really came into my own as “Mahler”’.

Begun in March, 1888 and completed in just six weeks, it was conceived as ‘a symphonic poem in two parts’ – a description Mahler demurred from for a performance in Hamburg in 1893. By then, he had decided, it was a symphony pure and simple but, bowing to contemporary fashion for programmatic music, he affixed a telling subtitle: Titan.

The name was borrowed from an epic novel by the German Romanticist Jean Paul. Published in four volumes between 1800-03, it presented a sentimental portrait of a solipsistic young man beset by emotional tragedy who grows fitfully into maturity through his finding of true love and absorption in nature. It’s easy to understand the attractions it must have held for an emotionally fragile young composer then in love with the wife of another man, and newly embroiled in a professional spat with Artur Nikisch, his co-conductor at the New State Theatre, Leipzig.

Considerably more significant had been Mahler’s transformative encounter with Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Youth’s Magic Horn), an anthology of German folk poems and songs published between 1805-08. Ripely romantic in its blending of realism and fantasy, its tales of daring soldiers and despairing wanderers, its powerful sense of nationalism rooted in nature, and its intoxicatingly heightened emotions were at the beating heart of Germany’s creative life in the 19th century. It penetrated deep into Mahler’s psyche, too, influencing him as nothing else did.

The First Symphony is a vast, compelling narrative that follows the titular Titan from primal birth into personal and public Hell, and redemptively onwards to Paradise, on a journey of boundless dimensions. Originally cast in five movements, Mahler tinkered with and revised the First Symphony until 1906, just five years before his death. An early casualty was the mooted second movement, ‘Blumine’. Discarded (along with the narrative suggestions initially supplied for each of the movements) to lend the symphony a more Classical than Romantic appearance, it lay forgotten until its rediscovery in the 1960s.

What remained was an ardent declaration that defined Mahler’s artistic credo. If, as he claimed, ‘the symphony is a world’, then his first essay in the form can surely claim to be the dawn of a new orchestral cosmos. One in which Mahler’s attraction to the primitive pleasures of folklore and nature, his conviction in the transcendent power of music and his determination to forge a new vocabulary for the symphony were given articulate voice.

It begins with a dazzling statement, simultaneously delicate and robust, in which cuckoo calls in woodwinds herald nature’s awakening at daybreak. Imaginative orchestral colouring and a host of telling details – notably a far-distant hunting song and a lithesome duet between cellos and woodwinds that borrows a

theme from Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (Songs of a Wayfarer) – prompt what the critic Ludwig Schiedermair has described as a ‘jumbling of the various motifs [that] seems as if nature... now bursts forth’.

The Second Movement also recycles song material to mimic the rustic earthiness of the traditional Ländler country dance. Hints of the more untameable magic of nature are heard in the agitated interplay of high and low strings tempered by the bold certainty of the brass section and distinctly tongue-in-cheek commentary of woodwinds.

Mahler imbued the Third Movement with a macabre humour, marking it to be played ‘Mit Parodie’. There’s an echo of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition at its darkest in the evocative use of ironically lowering horns, while the quotation from the popular song Frère Jacques is buffered, in a sop to contemporary audiences, between recognisably Hungarian and Yiddish influences. The middle section again quotes from the Wunderhorn -inspired Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen before giving way to a lugubrious funeral march.

The Finale begins with nature at its most tempestuous: a Tchaikovskian swirl of spiky horns punctuating and peppering a maelstrom of strings, woodwinds and percussion. A soulful, song-like interlude (its lovely, lilting theme taken from the deleted ‘Blumine’ movement) briefly appears before being swept away by another orchestral storm. What follows, in the ensuing calm, is an almost cinematic traversal of earlier themes, the orchestra growing in strength, confidence and power to iterate a new optimism.

With concluding passages marked by Mahler as ‘Höchste Kraft’ (‘With supreme power’), ‘Vorwärts’ (‘Forwards’) and the self-explanatory ‘Triumphal’, the rousing apotheosis of the ending has been appositely described by the Mahler apostle Paul Stefan as ‘like a chorale from Paradise after the waves of Hell. Saved!’

Notes by Michael Quinn © National Concert Hall

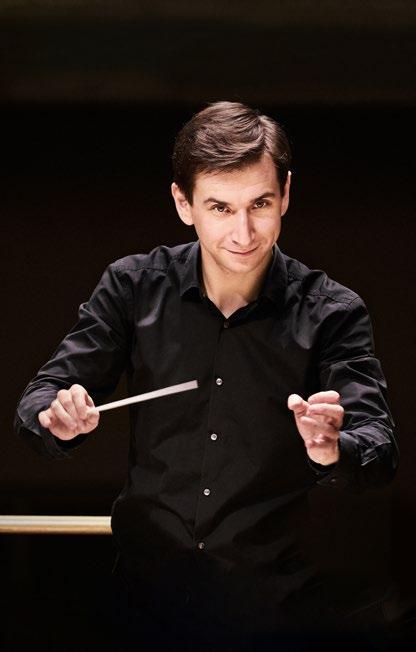

‘EXPRESSIVE CHARM, CLEAR TECHNIQUE AND METICULOUS ATTENTION TO DETAIL’

Combining expressive charm, clear technique and meticulous attention to detail, Mihhail Gerts has recently drawn attention for successful debuts with the Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, BBC Symphony Orchestra and Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France. With a passion for the music of his native Estonia, Gerts is Founder and Artistic Director of the TubIN Festival, honouring the work and legacy of Estonian refugee Eduard Tubin.

The 2023-2024 season sees return invitations to the Gulbenkian Orchestra, National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland, Ulster Orchestra, Dortmunder Philharmoniker, Odense Symphony, Estonian National Symphony and Orchestre National de Pays de la Loire in repertoire ranging from Monteverdi to world premieres by Signe Lykke and Toivo Tulev via Bach, Brahms, Ravel, Prokofiev and Arvo Pärt, whilst at the TubIN Festival he conducts Tubin’s Seventh and Eighth Symphonies.

In recent seasons Gerts has conducted the Staatskapelle Dresden, NHK Symphony Orchestra, Helsinki Philharmonic, Oslo Philharmonic, Sydney Symphony and City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestras.

He spent his formative years as Resident Conductor of the Estonian National Opera (2007-14) during which time he conducted over 40 different productions, followed by a period as Deputy GMD of the Hagen Theater (2015-17). As a guest he has conducted opera productions at Teatro la Fenice, Teatro delle Muse, Opera de St-Etienne and Belarus National Opera.

Gerts studied conducting at the Estonian Academy of Music and completed his PhD at the Hochschule für Musik Hanns Eisler in Berlin. He was invited onto the Deutsche Dirigentenforum from 2013 until 2017 and was a finalist at the Donatella Flick and Evgeny Svetlanov Conducting Competitions in 2014.

Dame Sarah Connolly studied piano and singing at the Royal College of Music, of which she is now a Fellow.

Among many other roles she has sung Dido (Dido and Aeneas) at Teatro alla Scala, Milan and the Royal Opera, Covent Garden; the Composer (Ariadne auf Naxos), Clairon (Capriccio), and Gertrude (Brett Dean’s Hamlet ) at the Metropolitan Opera, New York; Orfeo (Orfeo ed Euridice) and the title role in The Rape of Lucretia at Bayerische Staatsoper, Munich; the title role in Giulio Cesare and Phèdre (Hippolyte et Aricie) at Glyndebourne Festival Opera; Brangäne (Tristan und Isolde) at the Royal Opera, Glyndebourne Festival, Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona, and Festspielhaus Baden-Baden; the title role in Ariodante and Sesto (La clemenza di Tito) at the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence; Phèdre at Opéra national de Paris; the title role in Ariodante for Dutch National Opera and Wiener Staatsoper, and Fricka (Das Rheingold and Die Walküre) at the Royal Opera and Bayreuther Festspiele.

She has also made frequent appearances at Scottish Opera, Welsh National Opera, Opera North, and, particularly, English National Opera.

She has appeared in recital in London, New York, Boston, Paris, Amsterdam, Rotterdam, San Francisco, Atlanta, and Stuttgart; at the BBC Proms, and Schubertíada de Vilabertran; and at the Aldeburgh, Cheltenham, Edinburgh, and Oxford Lieder festivals. In concert she has performed at the Aldeburgh, Edinburgh, Lucerne, Salzburg, and Tanglewood festivals, and is a frequent guest at the BBC Proms where, in 2009, she was a memorable guest soloist at the Last Night.

She has recorded prolifically and twice been nominated for a Grammy Award. She was made a DBE in the 2017 Birthday Honours, having been made a CBE in the 2010 New Year Honours, and in 2012 received the Singer Award of the Royal Philharmonic Society in recognition of her outstanding services to music. She was awarded the 2023 King’s Medal for Music, an award given annually to an outstanding individual or group of musicians who have had a major influence on the musical life of the nation.

Get to know the people behind the instruments of the National Symphony Orchestra

Catriona Ryan flute, section leader

When did you join the National Symphony Orchestra?

That’s like asking a lady her age! I’ll just say I joined directly after graduating… it wasn’t today or yesterday!

Where did you study?

I began privately with Danette Milne, then studied with the legendary Doris Keogh at the Royal Irish Academy of Music, and with another illustrious teacher, Trevor Wye, at the Royal Northern College of Music.

Why did you choose to play your instrument?

Look at it! it’s stunning! That, and hearing James Galway’s Annie’s Song… I even bought the single!

What do you enjoy most about being in the NSO?

Having the good fortune to sit slapbang in the middle of the giant vortex of beautiful sounds as they’re being produced. Feeling each note pulsating through the stage gives me such an enhanced and incredibly privileged perspective.

Tell us your favourite NSO story/ memory so far.

Until recently I would have said being soloist in Mozart’s D major Flute Concerto in 2020, our first concert back

after the pandemic. I was bouncing off the walls with happiness to be onstage playing again. An equally beautiful experience was playing Fauré’s Fantaisie last year; the audience response was so warm and enthusiastic.

What made you decide to pursue a career in music?

I ultimately owe my career to a local curate in our parish as a child. Luckily for me, he felt that I had talent and persisted in telling my parents so, eventually handing them an ad for flute lessons from the local paper! He is now a monk in Glenstal Abbey. Thank you Fr. Fintan Lyons!

If you weren’t a musician, what would you most like to be?

A sculptor!

If you could have dinner with anyone (alive or dead) who would it be? It might involve time travel for some, but to have Sir David Attenborough, J.S. Bach, Michael Harding, Hilary Clinton, Tommy Tiernan, Chris Hadfield, Marcel Moyse (flute players will know), Barack and Michelle Obama, and maybe Dom Pérignon in the same room? That would be some shindig! Of course, the person I would most like to have dinner with again would be my lovely Dad.

The National Symphony Orchestra has been at the centre of Ireland’s cultural life for over 75 years. Formerly the RTÉ National Symphony Orchestra, it was founded in 1948 as the Raidió Éireann Symphony Orchestra. In 2022, the Orchestra transferred from RTÉ to the remit of the National Concert Hall.

Resident orchestra of the National Concert Hall since its opening in 1981, it is a leading force in Irish musical life through year-long programmes of live music – ranging from symphonic, choral and operatic to music from stage and screen, popular and traditional music, and new commissions – alongside recordings, broadcasts on RTÉ and internationally through the European Broadcasting Union. Schools concerts, family events, initiatives for emerging artists and composers, collaborations with partner promoters and organisations extend the orchestra’s reach.

As a central part of the National Concert Hall’s 2024-2025 Season, the NSO presents more than 55 performances shared between Dublin, Galway, Limerick, Waterford and Cork. They include collaborations with international and Irish artists, ensembles and conductors – including a number of events with the National Concert Hall’s Artists-in-Residence: the renowned American musician and composer Bryce Dessner, the internationally acclaimed Irish mezzo-soprano Tara Erraught, and the dynamic musician and presenter Jessie Grimes. The programme is rich and varied, presenting repertoire from across the centuries to the present day including world and Irish premieres, choral masterpieces, birthday and anniversary celebrations, family concerts and screenings, schools concerts, and professional initiatives for emerging singers and composers. A focus on nature and the environment is a central part of the season’s programming.

Highlights with the Artists-in-Residence are many. They include three Irish premieres by Bryce Dessner: Mari , his Violin Concerto performed by its dedicatee, Pekka Kuusisto, and his Concerto for Two Pianos performed by Katia and Marielle Labèque, for whom it was written. Tara Erraught performs virtuosic works by Mozart, Haydn and Marianne von Martínez, with historical performance specialist Laurence Cummings conducting, and arias by Mozart, Puccini, Bellini, Donizetti and Rossini, with Clelia Cafiero conducting. Tara is also the driving

force behind Celebrating the Voice, a week-long professional development programme for young singers which culminates in an opera gala with the NSO conducted by Anu Tali. Jessie Grimes leads immersive, family-friendly concerts including Our Precious Planet and explorations of iconic works: Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony and Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique as part of the ASD-friendly Symphony Shorts, as well as Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf, featuring new and specially commissioned shadow puppetry, and Britten’s The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra.

Other exciting highlights include Dame Sarah Connolly joining conductor Mihhail Gerts for Alma Mahler’s Six Songs; an 80th birthday celebration for conductor Leonard Slatkin which includes the world premiere of his son Daniel’ s cosmic journey, Voyager 130 ; Hugh Tinney performing Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto; Speranza Scappucci conducting a Ravel Birthday Celebration; John Storgårds conducting Rachmaninov and Shostakovich; Anja Bihlmaier conducting Mahler’s Ninth Symphony; and Ryan McAdams conducting the First Violin Concerto by Philip Glass with NSO Leader Elaine Clark as soloist; and John Luther Adams’ Pulitzer Prize-winning Become Ocean. Jaime Martín returns to conduct Chopin’s Second Concerto with Yeol Eum Son as the soloist, and former Principal Conductor Gerhard Markson returns for Stanford’s Requiem featuring the National Symphony Chorus and soloists including Máire Flavin and Sharon Carty.

World premieres by Deirdre McKay and Ailís Ní Ríain and, as part of Composer Lab, by Amelia Clarkson, Finola Merivale, Barry O’Halpin, and Yue Song all feature. Irish premieres include a new orchestral setting of Philip Glass’s film score Naqoyqatsi with the Philip Glass Ensemble; Stephen McNeff’s The Celestial Stranger with Gavan Ring as soloist; James MacMillan’s St. John Passion with the National Symphony Chorus and Chamber Choir Ireland; and Ukrainian Victoria Vita Polevá’s Third Symphony.

Additional family events include popular screenings of classic children’s stories by Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler – Stick Man and The Snail and the Whale – and Roald Dahl’s Revolting Rhymes . Music in the Classroom returns with Junior Cycle and Leaving Certificate Music Guide events, and Musical Adventures for Primary School children.

1st Violin

Elaine Clark •

Jens Lynen

Orla Ní Bhraoin °

Catherine McCarthy

Ting Zhong Deng

David Clark

Anne Harte

Bróna Fitzgerald

Sylvia Roberts

Claudie Driesen

Karl Sweeney

Molly O’Shea

Maria Ryan

Justyna Dabek

Erin Hennessey

Niamh McGowan

2nd Violin

Ruth Funnell

Elizabeth McLaren ‡

Joanne Fleming Campbell °

Rosalind Brown

Paul Fanning

Dara O’Connell

Melanie Cull

Elena Quinn

Magda Kowalska

Matthew Wylie

Gemma O’Keeffe

Hannah Choi

Susanna Poole

Simon-Philippe Allard

Viola

Ben Newton

Francis Harte °

Ruth Bebb

Neil Martin

Margarete Clark

Nathan Sherman

Anthony Mulholland

Alison Comerford

Carla Vedres

Róisín Ní Dhúill

Jenny Ames

Marianna Alaberdova

Cello

Martin Johnson •

Polly Ballard ‡

Violetta-Valerie Muth °

Úna Ní Chanainn

Filip Szkopek

Maria Kolby-Sonstad

Alex Acomb

Matthew Lowe

Yue Tang

Paula Hughes

Double Bass

Milad Daniari

Alice Durrant

Danny Vassallo

Waldemar Kozak

Helen Morgan

Elena Marigomez

Olaya García Álvarez

Nigel Smith

Flute / Piccolo

Catriona Ryan •

Ríona Ó Duinnín ‡

Sinéad Farrell †

Marie Comiskey

Oboe

Matthew Manning •

Sylvain Gnemmi ‡

Deborah Clifford †

Jenny Magee

Cor Anglais

Deborah Clifford †

Clarinet

Matthew Billing

Deirdre O’Leary

Fintan Sutton

Suzanne Forde

E-flat Clarinet

Suzanne Forde

Bass Clarinet

Fintan Sutton †

Bassoon

Greg Crowley •

Florence Plane

Contra Bassoon

Hilary Sheil †

Horn

Benjamin Hartnell-Booth

Peter Ryan

Bethan Watkeys †

David Atcheler ◊

Mark Bennett

Joel Ashford

Thomas Bettley

Dewi Jones

Trumpet

James Nash

Simon Bird

Pamela Stainer

Eoghan Cooke

Jonathan Corry

Trombone

Jason Sinclair •

Gavin Roche ‡

Paul Stone

Bass Trombone

Josiah Walters †

Tuba

Francis Magee •

Timpani

Niels Verbeek

Richard O’Donnell

Percussion

Rebecca Celebuski

Bernard Reilly ◊

Emma Crossley

Harp

Andreja Malir •

• Section Leader

* Section Principal

† Principal

‡ Associate Principal

° String Sub Principal

◊ Sub Principal 1

Go spreaga an ceol tú. Bain sult as ceol binn sa Cheoláras Náisiúnta. Is leatsa an Ceol. Is leatsa an Ceoláras Náisiúnta. nch.ie

ESB has a long heritage in supporting the arts. We believe the arts play a significant role in both documenting and harnessing social change and in creating a brighter future for all.

Head to esb.ie/arts to find out more.

National Concert Hall presents

Three New Recitals Curated by Award-winning Pianist Dearbhla Collins

Sean Michael Plumb baritone - Sun. 20 October 3pm

Paula Murrihy mezzo-soprano - Sun. 1 December 3pm

Anthony Léon tenor - Sun. 12 January 3pm

Dearbhla Collins pianist

Kevin Barry Recital Room