44 minute read

Around the Coasts & Market Reports

Gulf/South Atlantic

Louisiana diversion project will alter fi sheries

Environmental study predicts ‘major, adverse, permanent’ effect on shrimp, oysters

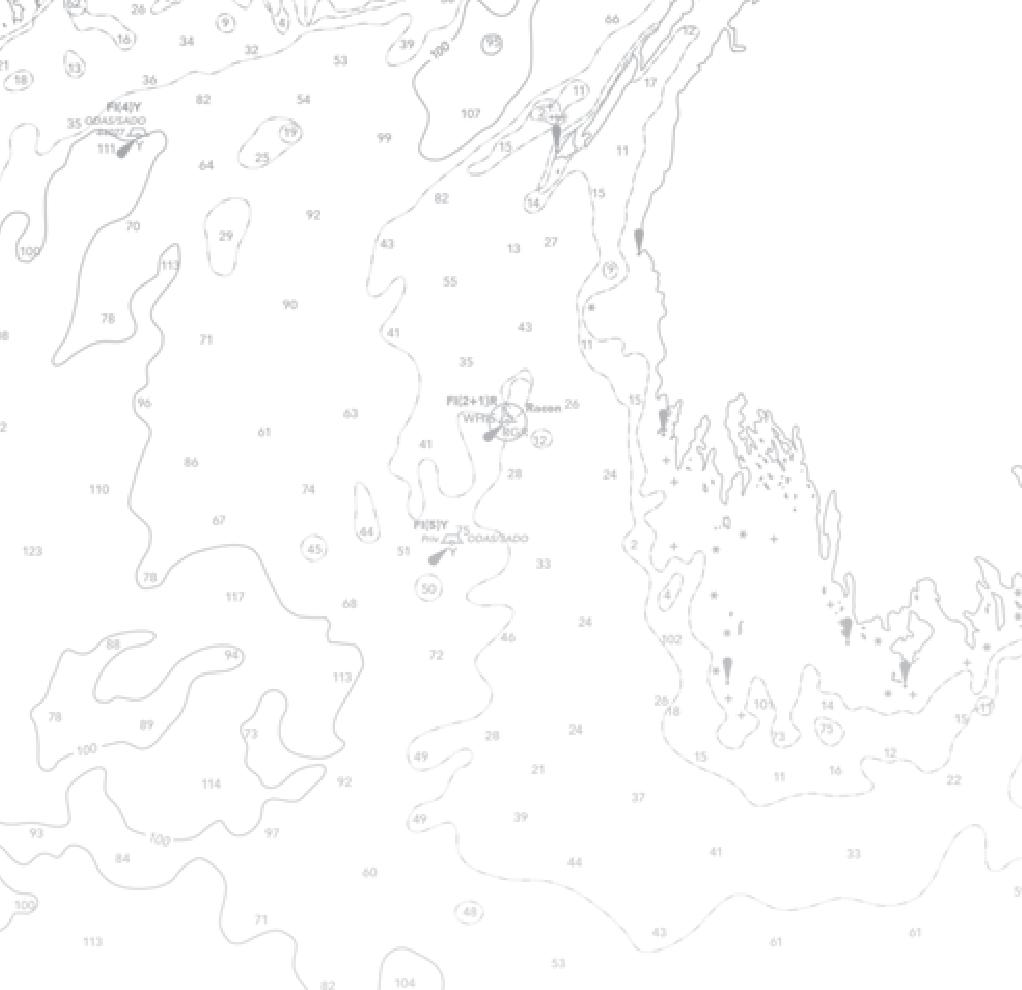

The Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion project would be built on the right descending bank of the Mississippi River in Plaquemines Parish, La.

An Army Corps of Engineers environmental impact statement for the planned $1.4 billion Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion project acknowledges it will drastically alter the south Louisiana shrimp and oyster sheries — all in the name of saving the state’s coast.

“Moderate to major, adverse, permanent direct and indirect impacts are anticipated on shrimp sheries in the project area due to expected negligible to minor, permanent, bene cial impacts on white shrimp, and major, permanent, adverse impacts on brown shrimp abundance,” states an executive summary of the report, issued March 5.

While it may be possible for shermen to target other species, that “would require additional investment by individual shers, which may or may not be nancially feasible,” the report adds. “Declines in shrimp abundance may also exacerbate trends in the aging workforce to leave the industry.”

Projected to be built over ve years, the diversion plan by the state Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority could be the rst of similar projects for bringing new sediment into south Louisiana’s steadily eroding coastal lands and marshes, instead of sediment washing out from the river mouth straight into the Gulf of Mexico depths.

Project supporters say it’s essential to maintaining the state’s land mass and hurricane protection for New Orleans and other communities. Critics — including much of the state’s seafood industry — want to see alternatives that won’t dramatically alter their livelihoods.

“All of us in the sheries industry knew this all along,” said George Ricks, president of the Save Louisiana Coalition, which has argued for dredging and other methods to move sediment instead of freshwater diversion. “The CPRA has always downplayed the e ect on sheries.”

“The Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion is the largest project of its kind ever undertaken in U.S. history, and represents an unparalleled, innovative coastal restoration e ort unlike anything else in the world,” said Chip Kline,

MARKET REPORT: Blue Crabs Crabbers watching nearby states after tight supply in early 2021

ulf of Mexico crabbers navigated

Ginto the uncertain waters of spring 2021, a year that began with a dearth of product.

“There’s nothing since Christmas,” said long-time crab dock owner Trudy Luke of Houma, La., whose family members also regularly harvest blue crabs. “The demand is so high that docks are throwing money out there. I’ve got a fi sherman here who usually brings in 100 55-pound pans. Today he brought in 10.”

Louisiana accounts for more than 30 percent of all blue crab landings in the United States, and a lion’s share of Gulf of Mexico landings.

High prices at the dock don’t have a positive effect on fi shermen when catches are small, particularly with rising fuel prices.

Currently, Louisiana crab prices for the largest specimens in March were as high as $4.25 per pound, industry participants said. Number 2 crabs were fetching $2.25 per pound, and very small males about $1.

“Something happened with the weather, the wind and the cold, so in eastern Louisiana crabbers are working the offshore edge right now, but it’s mostly female crabs,” said Pete Gerica, chairman of the Louisiana Crab Task Force. “So right now, the prices are going out of the box. This has been a trend now for the past three years, and the demand is for more than the amount of product being produced.”

A three-year program of halting crab harvesting during specifi ed months in Louisiana — recommended by crabbers and processors — has had positive population effect. This is one reason why crabbers are optimistic that as waters warm, the supply will be greater.

Since the creatures migrate east to west, Louisiana crabbers anticipate good indications of a comeback when Mississippi, Alabama and Florida show increases. — John DeSantis

— George Ricks, SAVE LOUISIANA COALITION

chairman of the Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, in a statement after the EIS release.

Overall, the Barataria Basin has lost more than 276,000 acres of land since the 1930s, a process accelerated by damage from the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, according to NOAA. With other government agencies NOAA foresees spending up to $2 billion on restoration; a series of public comment and virtual hearing events online were scheduled through May 4.

CPRA planners say the project would add more than 17,300 acres of land in the Barataria Basin over 30 years and reduce hurricane storm surge levels by a foot in communities north of the project location in Plaquemines Parish.

Project boosters say building the new land can generate 12,400 jobs. But it will come at a long-term cost, according to critics. The Corps paper bears out their fears.

Freshwater species could thrive amid the redirected river ow, but commercially valuable saltwater species would decline, as would the Barataria Bay population of bottlenose dolphins, the report says.

While rebuilding marshes would eventually increase habitat for shrimp, those later years “would not substantially alter the stated impacts on the shrimping industry in the project area,” the Corps review predicts.

Louisiana shermen landed $34.6 million worth of brown shrimp in 2019, “and 31 percent was from Barataria Bay, so right out of the gate (with diversion), you lose $11 million,” said Ricks. — Kirk Moore

Boat of the Month

Home-built Carolina net reel boat

North Carolina / mullet, spots, Spanish mackerel

Jacob Willis

orn and raised in North

BCarolina, Jacob Willis started shing at age 15. Ten years later, he’s learned a lot.

Willis started his journey dropnetting with his father. While the rest of the family enjoyed shing, Willis fell in love with the profession.

He started saving money, purchased his shing license and started buying ounder and speckledtrout nets.

At age 18, Willis moved to Georgia to work on the deck of a 75-foot trawler named Lady Susie II.

He moved up the chain to captain but quickly learned that life on a trawler wasn’t for him, so he returned home and started shing for ounder and trout full time in North Carolina.

“In 2019, they passed the largemesh net ban and it about knocked me down,” says Willis. “But I knew I had to go bigger, so I started building my net reel boat.

“It was a huge learning curve for me, but with a little luck, a lot of faith and hard work, I was successful. I couldn’t have done it without the help of a lot of local shermen that extended a hand to me.”

Willis has a plan to grow larger and add boats to work strictly in the ocean.

“The best part about it is I really love the profession,” says Willis. “Knowing it’s all on me — I don’t have to be at a place at a certain time, I don’t have to report to a job where I have a boss, and I love the fact that I can provide a part of the freshest seafood in our state.”

Willis also knows there will still be dif culties.

“What I really want people to know is that it’s hard being controlled by the prices and a new law popping up every other month. Unfortunately most people don’t like commercial shermen, but I’m not out there to take from anyone or destroy a shery.” — Maureen Donald

Boat Specifi cations

HOME PORT: Oriental, N.C. OWNER: Jacob Willis BUILDER: C-Hawk YEAR BUILT: 1984 FISHERIES: Primarily sea mullet, spots, croakers and Spanish mackerel HULL MATERIAL: Fiberglass LENGTH: 25 feet DRAFT: 2 feet CREW CAPACITY: 2 PROPULSION: 250-hp four-stroke Suzuki outboard TOP SPEED: 35 mph FUEL CAPACITY: 75 gallons

Alaska

Despite high demand, Bristol Bay base price sinks

BBRSDA paper cites covid-related costs and suggests solutions for shermen

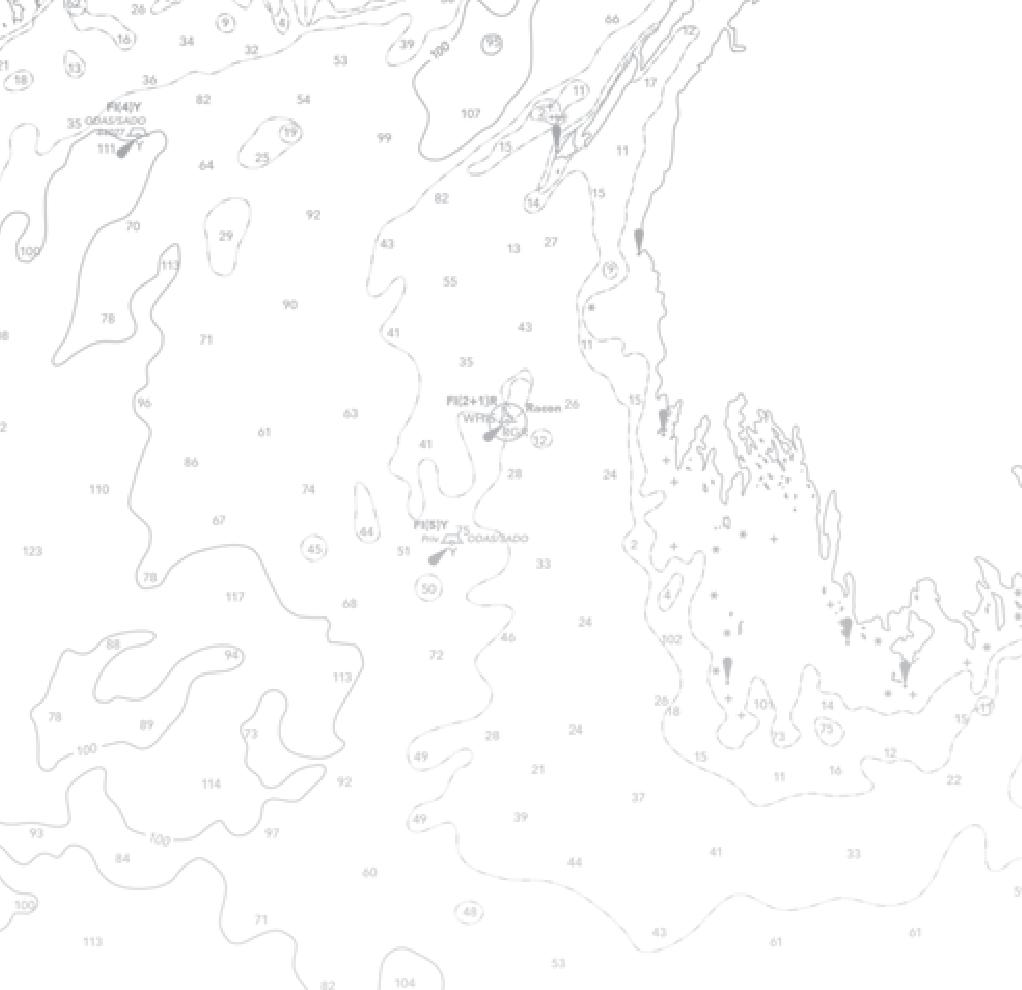

espite record retail prices and D a consistently strong demand, Bristol Bay salmon shermen saw a nearly 50 percent drop in their base ex-vessel price in 2020 — from $1.35 a pound in 2019 to $0.70 in 2020. That’s a 65-cent drop in a single year.

The Bristol Bay Regional Seafood Development Association published a new report that lays out likely reasons for the low base price. It also o ers the

A new report details factors behind the sharp drop in base price for 2020 Bristol Bay salmon.

region’s shermen a range of solutions to consider for the future, and is seeking feedback from stakeholders to help set goals for the association.

“Demand for Bristol Bay sockeye is very high. Retail prices are at record levels. Anecdotally, wholesale prices are at to up compared to last year — signi cantly so for once-frozen llets,” says the BBRSDA’s white paper, released March 1. “When consumer prices are high or increasing for a product, the underlying raw material price usually goes up, not way down. In short, 2020 should have been a terri c season for Bristol Bay shermen and ex-vessel prices, but it wasn’t (or at least it hasn’t been thus far).”

Though the 2020 season is long over, the vast majority of bay shermen operate under the “open-ticket” system, according to Andy Wink, executive director of the association. That system typically results in an additional payment the following year.

Under the open ticket system, the boat owner/operator communicates with a processor ahead of the season to establish a commitment to deliver or purchase sh, “but no price is committed to,” Wink told NF. With each delivery during the season, shermen receive a sh ticket from the processor, which is a receipt of the delivery and transaction. The price is typically left blank until after base prices are announced — usually at least halfway into the season, according to Wink.

The base price is capped o with a bonus or retro, which is based on processor gains or losses in the market long

MARKET REPORT: Pacifi c Cod Gulf cod stocks creep back, but Bering and Aleutian still down

aci c cod stocks have begun to reP bound in the Gulf of Alaska, but the TAC for 2021 remains low at 17,321 metric tons. Last year managers curtailed the shery in federally managed waters after stock assessments put the biomass near the bottom of the threshold for conducting the shery.

Though the recruitment of younger cod and the uncaught sh from last year have added to the abundance in most recent assessments, full recovery of the stock could take years. The warm-water blob of 2014 has been blamed for the crash.

Stocks also continue to decline in the Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands harvest areas. The 2021 TAC for the Bering Sea has been set at 111,380 metric tons with a TAC of 13,796 metric tons for the Aleutian Islands.

The 2020 TACs for the respective areas had been set at 141,799 metric tons and 14,214 metric tons.

As for this year’s harvest the cod and pollock eets got off to a rocky start after covid cases caused the intermittent closure of large processing plants in Dutch Harbor and Akutan. In state-managed waters the Alaska Department of Fish and Game reported that the pot eet had landed 1.89 million pounds, slightly over their 2020 TAC of 1.88 million pounds. Most of the early-season effort took place in the waters near Kodiak.

“Fishing in February was pretty middle of the road, neither fast nor slow,” says Nathaniel Nichols, an area management biologist, in Kodiak. “There was a good mix of sh size reported from vessels. Average weights were a little higher than usual.”

According to a NMFS ex-vessel value database, prices ranged from 35 to 39 cents per pound going into 2021. Dockside deliveries to processors in Kodiak during February ranged from 30 cents to 55 cents per pound, depending on size and quality. — Charlie Ess

after the season has closed in July. (The 2020-21 retail year closes at the end of May 2021.)

Though the payout timing on retros varies, “usually they are announced in the spring,” Wink adds.

“As the largest organization representing Bristol Bay shermen whose mission is to maximize shery value for the bene t of its members, ex-vessel price is obviously a key concern for the Bristol Bay Regional Seafood Development Association,” the paper says.

“This lower [2020] price equates to loss of $130 million in total ex-vessel value compared to 2019, or roughly $75,000 per driftnet vessel,” the organization reports.

As bay shermen look ahead to their retro pay for the 2020 season, there’s been a lot of chatter about the processors’ risks — as well as rewards — for a highly successful Bristol Bay sockeye salmon season in an otherwise extremely di cult year.

“Frustration and confusion over the ex-vessel price were common themes in nearly every interaction BBRSDA board and sta members have had with the eet since last season,” the paper says, “in addition to numerous social media posts and comments.”

A recent BBRSDA survey of shermen showed that transparency on the part of processors’ reasoning for setting a low base price was the most important issue facing the eet.

As the association attempts to take next steps in securing fair prices for its eet in the years to come, it notes in the paper that technically the majority of the region’s processors are under no obligation to do more.

“We’ve heard that processors deeply value shermen as key partners, and some have expressed a desire to have more transparent communication,” Wink told NF. “However, there is concern about having too much transparency and public disclosure, and uncertainty about how to be more detailed in their communications without sacri cing privacy.”

And there is still a possibility for a “This fi shery has a bright future. And although it may feel as though the fi shermen’s options are limited, you own something truly unique: access to world’s most abundant supply of premium wild salmon.”

— Bristol Bay Regional Seafood Development

Association 2020 base price report

good retro check to come.

“It’s certainly possible that shermen will be paid signi cant retros ahead of [the 2021] season,” the white paper says. “However, let’s be clear about two things: processing companies are not contractually obligated to 1) pay any more than they have already committed to or 2) share any more information about sales performance than they choose. Even if processors could pay a higher price, there is no contractual requirement to do so without Silver Baystyle pro t sharing agreements.”

Processor prices are “based on what suits their short and long-term needs best,” the paper says.

The BBRSDA notes the primary factors for the low base price: Increased business risk and additional operating costs because of covid, two tough years for processors in 2020 and 2019, and a compressed season that led to lower production of higher-value product forms.

The next step, however, is up to shermen, says the BBRSDA. “This shery has a bright future,” the white paper says. “And although it may feel as though the shermen’s options are limited, you own something truly unique: access to world’s most abundant supply of premium wild salmon.” — Jessica Hathaway

Warrenton, Ore.

Skipper Stewart Arnold snapped this pic of his crew on the Pacifi c Future: Trenton Garlock, Jose Abundiz and Leo Rodriguez. After many months of domoic acid, we fi nally got to go fi shing. And some good fi shing it was! With 42x14 pots, it’s smiles all around. The price is high, and the crabs are plentiful. This is your life. Submit your Crew Shot www.nationalfi sherman.com/submit-your-crew-shots

Atlantic

Department of Interior reverses on Vineyard Wind

BOEM report seen as Biden administration green light to offshore wind power

oving quickly on the Biden

Madministration’s renewable energy agenda, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management completed its environmental review of the 800-megawatt Vineyard Wind plan, clearing the path for the rst truly commercial-scale U.S. o shore wind project.

“The United States is poised to become a global clean energy leader,” said

Vineyard Wind would install 84 GE Haliade-X turbines on its lease off southern New England.

Laura Daniel Davis, a deputy assistant secretary in the Department of Interior, in announcing the step March 8. “To realize the full environmental and economic bene ts of o shore wind, we must work together to ensure all potential development is advanced with robust stakeholder outreach and scienti c integrity.”

Located about 15 nautical miles o Martha’s Vineyard, Mass., Vineyard Wind

MARKET REPORT: Herring As catch limit screws tighten, bait dealers seek alternative sources

ew rules in the herring shery N aimed at improving sustainability for the important lobster bait sh are impacting shermen, dealers and others. The 2021 shing season started Jan. 1, with an annual catch limit of 11,571 mt. However, once Framework 8 to the herring management plan is implemented, the total ACL will be set to 4,128 mt. The 2020 stock assessment shows spawning stock biomass to be at its lowest value since the late 1980s. Wayne Reichle, president of Lund’s Fisheries in Cape May N.J., calls the quota reductions “a disaster for the region’s herring shery.” Reichle says the eet has stayed within quota the last few years, so the low biomass and poor recruitment is “attributable to the stress of a cold-water sh being challenged by a warming ocean.” Many say it is too early to predict to what extent herring supplies will affect prices, given the newest reductions. In mid-March, prices in Maine were about $250 per barrel at the docks.

Brittany Willis, general manager of JBR Maine, a wholesale bait and lobster company with four locations in Maine, says this year may not look much different than last.

“Demand is always high, but the supply just isn’t here,” Willis says. “Last season, I think we expected the herring price to skyrocket more than it did. But because pogies were so abundant, the prices for herring weren’t as high as expected.

Meanwhile, adds Reichle, “domestic markets will meet demand using other domestic species or importing herring from other origins.” This year, a lot of bait dealers have turned to other states or Canada to ll herring supply gaps. “And the menhaden shery has de nitely helped ll that gap,” says Willis. “We’re really focused on trying to nd those new species,” says Willis, “to ll the gap with all the restrictions on herring and pogies.” — Caroline Losneck

is viewed as a bellwether for the nascent U.S. o shore wind industry. Its rapid progress in recent weeks is a 180-degree turnaround from December, when Trump administration appointees at Interior moved to kill the permitting process.

Fishing advocates saw that as a major victory in their e ort to get the industry a bigger say in BOEM’s wind energy siting and permitting processes. But with the Biden administration strongly committed to developing more renewable energy, the tide is running the opposite way, to the dismay of those advocates.

“It would appear that shing communities are the only ones screaming into a void while public resources are sold to the highest bidder, as BOEM has reversed its decision to terminate a project after receiving a single letter from Vineyard Wind,” said the Responsible O shore Development Alliance, a coalition of shing groups and communities.

BOEM should “at least hold public hearings explaining to the public how a private company can resume a project terminated by the federal government without further inquiry,” the group said. “Unlike o shore wind advocates who lack an intricate understanding of our

— Responsible Offshore Development Alliance

marine ecosystems, the late stages of the environmental review projects do not leave many commercial shing communities with optimism, excitement, or hope for their existence.”

Other maritime industry groups hailed BOEM’s move. “A timely and effective permitting regime is a necessity in developing the generational energy and economic opportunity of o shore wind. With Interior’s announcement, we are closer to that reality,” said Erik Milito, president of the National Ocean Industries Association.

It has been a twisting path for the Vineyard Wind plan review, which appeared to be on a smooth glide path in summer 2019. Vineyard Wind had obtained its o shore lease from BOEM at auction in 2015, submitted permit applications in 2017 and the following year won an o shore power contract with Massachusetts.

But then the Greater Atlantic regional o ce of NMFS refused to sign o on a draft environmental impact statement, citing a need for more sheries data and study of potential cumulative impacts of wind energy development o the East Coast.

BOEM went back to the drawing board and in June 2020 completed a supplemental impact study. As the agency moved closer toward a nal record of decision, Vineyard Wind o cials abruptly withdrew their construction and operations plan, saying they needed

Snapshot Who we are

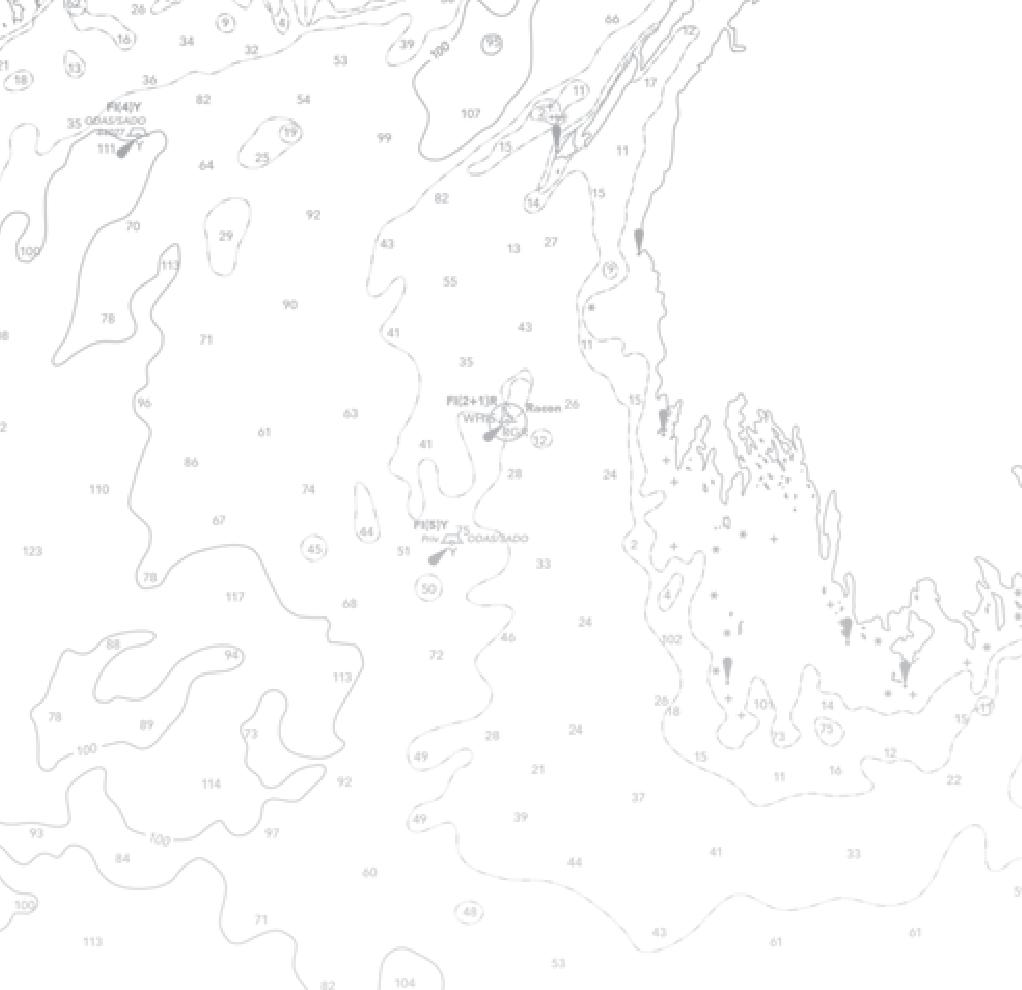

Ben Ahrens / Butte and Ekuk, Alaska

tart with a good bit of Bristol

SBay mud, sand and powerful tides, toss in huge sockeye salmon runs and a fi shing family that runs four generations deep, and you’ve got the recipe for what keeps Ben Ahrens returning each year.

Ahrens, 41, came from Nebraska to Alaska on a scholarship, then met his wife-to-be, Shelby, in a student teaching gig during the school year.

“It was only supposed to be for a semester,” Ahrens says.

When the season turned to summer, Ahrens got swept into an extended fi shing family in a full-blown setnet operation about 5 miles outside of the small settlement of Ekuk. That meant lugging 1,800 feet of 3/4-inch line from shore to beyond the low tideline, driving stout metal stakes into the deep mud and learning to pull nets to shore with four-wheel-drive pickups.

“It was different — and interesting,” he says.

Ahrens immediately took to the fi shing life and couldn’t wait to return.

Time and tides have a way of sparking romance, and it wasn’t long before Ahrens presented Shelby with an engagement ring.

“I proposed to my wife with a ring in a fi sh’s mouth and everything,” he says. That was in the summer of 2006, and the couple married in 2007.

Along came their three sons, Brayden, 11, Colben, 9, and 7-year-old Laeth.

These days, Ahrens works for the

Alaska Railroad, but he racks up all of his vacation time for the glorious time he gets to spend out in the fi sh camp each summer. “It’s like going camping for three weeks,” he says, adding that his family bunks in a 20-by-20-foot cabin on the beach. “But we leave all the phones and the electronic devices back at home (Butte, Alaska, in the off-season). It makes us grow so close together as a family.” — Charlie Ess

to update it for using larger, more powerful GE Haliade-X turbines, reducing the number of installations to 84 machines.

With little more than a month before the end of the Trump administration, its top Interior o cials said Vineyard Wind’s decision meant it would need to reapply and started the process over.

Two days after President Biden’s Jan. 20 inauguration, the company sent BOEM a letter asking to resume the environmental review.

Now, BOEM is working toward “a record of decision whether to approve, disapprove, or approve with modi cations the proposed project,” Interior o cials said. “The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the National Marine Fisheries Service will sign this joint record of decision for their respective authorization decisions.” — Kirk Moore

Looking for more news?

National Fisherman is the only publication that covers the entire U.S. commercial fi shing industry. For daily updates, visit nationalfi sherman.com/news

West Coast/Pacifi c

Two crew die in dangerous Dungeness season

Deadly capsize on Tillamook Bay bar one week after ‘dump day’ distress calls

The F/V Coastal Reign capsized outside of Garibaldi, Ore., on Saturday, Feb. 20, killing two members of its four-person crew.

he 38-foot Dungeness crab boat

TCoastal Reign capsized while crossing the bar in Oregon’s Tillamook Bay, heading into Garibaldi on Feb. 20. Of the four crew members, two survived the capsizing.

It was already a troubled week for the Dungeness eet, when the Coast Guard issued small craft restrictions but had not closed the Tillamook Bar. On its crossing, the Warrenton, Ore.-based Coastal Reign turned sideways in the surf and capsized at 4:40 p.m. The Coast Guard responded with rescue boats and a helicopter from Astoria, as other shing boats assisted.

Three crew members were rescued form the water, while a third was able to climb the rocks of a jetty and get rescued by the aircrew. Two crew members, Todd Chase and Zach Zappone, died.

The season had started with “dump day” on Feb. 13, when shermen dropped pots ahead of the o cial open on Tuesday. The Coast Guard Station Cape Disappointment responded to three distress calls that morning.

Station Cape Disappointment and Station Grays Harbor launched 47-foot lifeboat rescue crews at 7:30 a.m. for the Terry F. as it was taking on water near Willapa Bay. A Coast Guard helicopter hoisted three crew and the captain’s dog o the capsized crab boat.

— Lt. Jessica Shafer, COAST GUARD STATION

CAPE DISAPPOINTMENT

The crew was then diverted at 9:15 a.m. to the vicinity of Gearhart, Ore., to assist another shing vessel with a crew member who had been injured after the boat was struck by a wave. The lifeboat rescue crew transferred a rst responder to the vessel in 16- to 18-foot seas. With a head laceration and foot injury, the injured crew member and was able to remain on the shing boat while it

MARKET REPORT: Spiny Lobster After pandemic low-price worries, season could bring new highs

f this year’s season goes anything

Ilike last year’s, California’s spiny lobster divers can expect onagain-off-again product ow to mainstem markets in Asia in sync with rhythms of covid outbreaks and recessions. But trade wars between China and Australia could jack exvessel prices to new highs.

According to data from PacFIN, spiny lobster divers in 2020 landed 329.5 metric tons of the critters for an average ex-vessel price of $19.09 per pound for revenues of $13.87 million. So far in 2021 the eet put in 88.9 metric tons at average ex-vessel prices of $27.34 per pound for revenues of $5.36 million.

Those are the averages. Conditions varied widely during the 2019-20 season, which began in early October of 2019 and ended on March 18, 2020.

Covid set in right at the tail end of the 2019-20 season, and prices dropped from $13.92 per pound at the tail end of January to $10.62 per pound.

“This decrease was a direct result of the impact of the covid-19 pandemic and the closing of international seafood markets,” says Jenny Hofmeister, an environmental scientist with the Invertebrate Program with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, in San Diego. “Though concern was raised about a depressed market and continued low price, when the 2020-21 season opened in October 2020, spiny lobsters sold for an average of $14.88 per pound during the rst week of the season.”

By the end of December, Hofmeister notes that the ex-vessel prices jumped to a record $38.70 per pound. In March, she reported that prices had stabilized and were hovering near $20 per pound.

As for the coming season, Hofmeister and her team anticipate increases in effort as based on last year’s prices that went through the roof . — Charlie Ess

transited the Columbia River bar with the lifeboat crew as an escort until the 62-foot crab boat was moored in Ilwaco, and the patient was safely transferred to EMS.

Meanwhile, another lifeboat crew was assisting the crew of the 66-foot F/V Noyo Dawn o Long Beach, Wash. With ve people aboard, the vessel was disabled and drifting to shore, dragging its anchor. In 16- to 18-foot seas, the lifeboat crew placed the vessel in tow and began the transit south. With the increased risk of crossing the bar, the lifeboat crew from the Terry F. rescue joined to assist with the tow of the Noyo Dawn. The ebb tide was strong enough that at several points, all three vessels were unable to make any headway. The Noyo Dawn was taken to a pier in Warrenton, Ore., and safely docked around 9:30 p.m.

“The actions of the Coast Guard small-boat crews throughout the day were phenomenal, but so were the actions of the crews we assisted,” said Lt. Jessica Shafer, commanding o cer at Station Cape Disappointment. “When our boat arrived on scene with the distressed vessel in Long Beach, the shing vessel's crew had already donned their survival equipment. They knew what attachment points would be the strongest to use, and they were e cient at bringing our assistance lines over and attaching them. Those precious few moments can make all the di erence.” In all, the Cape Disappointment boat crews spent 28 hours underway in seas up to 20 feet. — Jessica Hathaway

Family members have disclosed that those lost were Todd Chase and Zach Zappone. Both families have started GoFundMe pages to help recover from the loss of their loved ones.

BRI DWYER PHOTO

Become a member

Access to free in-depth reports, a community forum designed just for you and so much more – a free membership to NationalFisherman.com will help you stay connected like never before. Sign up today and join the conversation!

Get started at

nationalfisherman.com/become-a-member

Tipping points

Scandies Rose hearings bring to light weak links in industry practices

By Jessica Hathaway

“T he Scandies Rose was built to last.” Those were the words of longtime marine surveyor Erling Jacobsen, who had inspected the F/V Scandies Rose several times over the last two decades before she was lost to the Bering Sea with fi ve of her seven crew on New Year’s Eve in 2019.

From Feb. 22 to March 5, U.S. Coast Guard and National Transportation Safety Board called for public testimony from witnesses, investors, employees and a range of experts on vessel stability; industry safety; hull modifi cations and maintenance; and lifesaving practices, protocol and devices.

Scandies Rose sank Dec. 31, 2019.

Jessica Hathaway

Coast Guard swearing in at the hearing.

Brian Hagenbuch

Scandies Rose captured by ROV.

Those who followed the hearings closely were reminded with each new witness of those lost with the Bering Sea crab and pot-cod boat, as they o ered their condolences to the survivors and loved ones of Captain Gary Cobban Jr., David Cobban, Seth Rousseau-Gano, Arthur Ganacias and Brock Rainey.

Some of the most memorable moments included the testimony of the accident’s two survivors — deckhands Dean Gribble and Jon Lawler. But the full span of testimony may result in more than one tipping point in regulations, protocol and best practices for Alaska’s winter pot sheries.

Among the most compelling — and telling — testimony was a panel of naval architects. Paul Zankich, Bud Bronson and Jonathan Parrott, testi ed together, o ering decades of expertise on vessel stability, icing and gear loading.

The panel members referred to the International Maritime Organization’s “shoebox” analogy, which assumes ice collecting on vertical and horizontal surfaces but not inside the webbing of pots stacked on deck because the standards are general and not written speci cally for that kind of gear.

“We understand how the IMO came up with the standards they have for icing,” Bronson added. “But the crab shery in the Northwest Paci c is signi cantly di erent than anywhere else.”

Zankich speci cally pressed for better data speci c to pot gear.

“If you’re a crabber, you have to believe the Coast Guard standards, you have to believe the IMO standards, you have to believe your naval architect,” he said. “All of these three beliefs need review in this inquiry, because we are the naval architects who are asking our owners and operators to believe. And we rely upon the Coast Guard standard to believe and the IMO standard to believe. And honestly, I don’t believe those standards now.”

Regulations account for as much as 6/10 of an inch of ice accumulation on vertical surfaces and 1.3 inches on

horizontal surfaces — and uniform accumulation on those surfaces.

“Crab pots… can accumulate ice on the inside of the pots,” said Parrott. “And if you’ve got wind and weather coming from a certain direction, the pots on that side are going to be heavier, are going to accumulate more ice in it than pots on the other side.”

Parrott made the point that better data on pots is critical for the Bering Sea crab shery, but especially so because pot sheries are expanding in Alaska as the longline blackcod shery incorporates pots to protect the catch from sperm whale depredation.

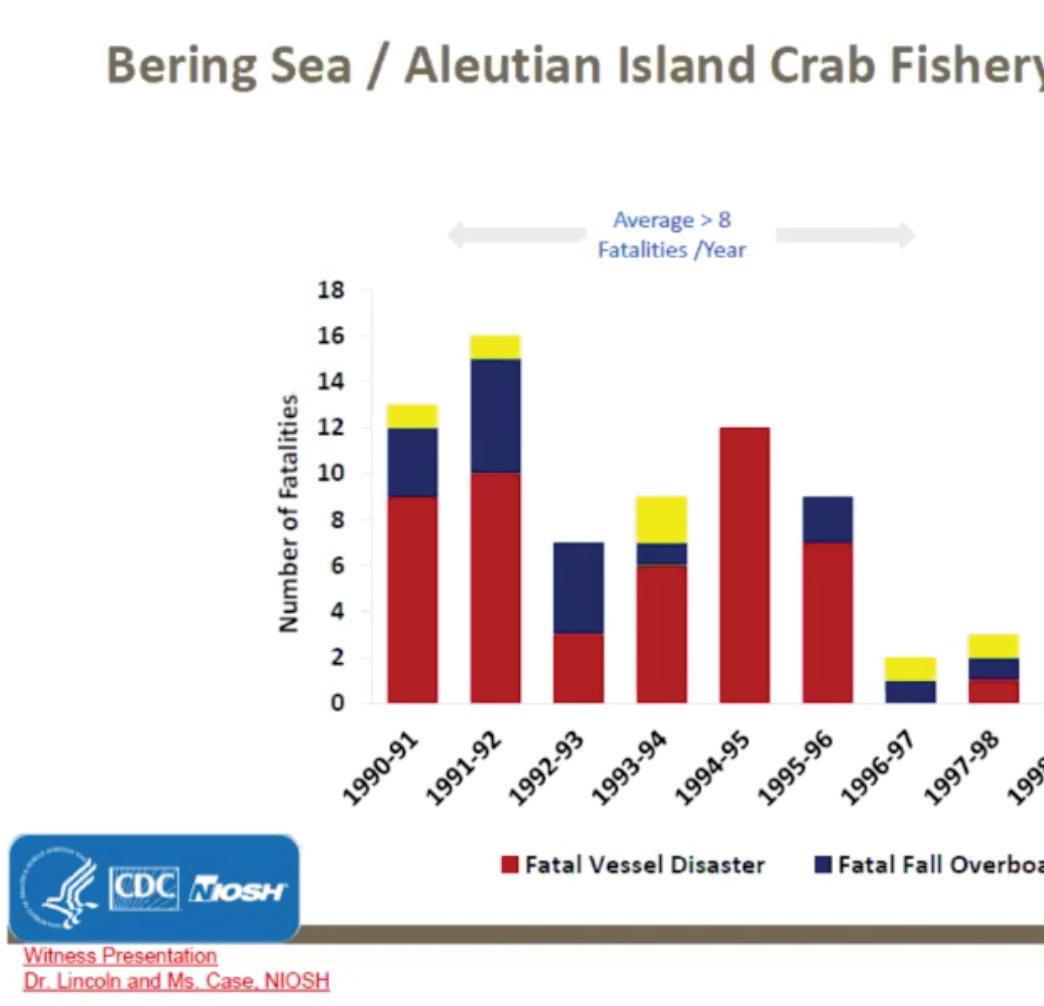

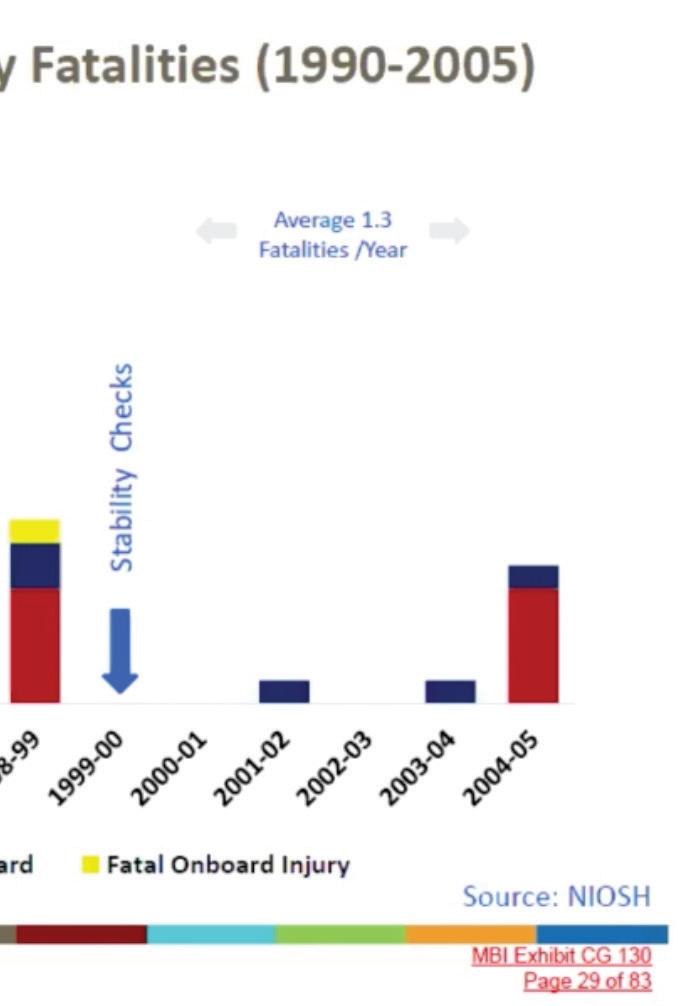

Stability has long been a focus for Alaska’s crab eet. After the Coast Guard implemented vessel stability and safety checks for the Bering Sea pot eet in October 1999, fatalities dropped from eight deaths a year in the 1990s to eight deaths over the next ve years, according to a report presented by Jennifer Lincoln and Samantha Case, representing the Commercial Fishing Safety Research and Design Program under the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

In 2005, managers rationalized the shery, giving each boat a set quota in place of the derby-style shery. NIOSH reports just one death in Bering Sea/Aleutian crab from 2005 up until the sinking of the Destination in 2017. The recent losses of the Destination and Scandies Rose — both with reputations of well-maintained boats with experienced captains and crews — have rocked the industry.

USCG

Coast Guard sprayed-down pot.

USCG

Scandies Rose loading pots.

“Capsizings like this are associated with the opilio shery, almost always when the boat has a full load on and is going out for the initial drop,” Chris Woodley, a retired U.S. Coast Guard captain, longstanding safety advocate and now executive director of the Ground sh Forum, told NF.

The Scandies Rose was readying for opilio crab season, but rst the crew would sh as much of the Paci c cod pot season as they could squeeze in.

“Are these boats overloaded? If you are using the icing criteria, then what you could carry would probably be a lot less. A boat that could carry 200 pots in non-icing conditions could be, say, 150 in icing conditions,” Woodley told NF. “From an enforcement perspective, the Coast Guard never really crossed that threshold because there are so many other variables.”

The inquiry heard testimony on a wide range of those variables, including loading and stability, weather, fatigue, safety equipment, hull maintenance, and shing seasons. Lawler testi ed that they

Jon Lawler Dean Gribble seemed to be in a hurry to get out, and that cod season was possibly why. The over-60 cod boats had had a short season the year before, starting on Jan. 1.

“The year prior to this, their season closed on the sixth of January,” Lawler testi ed. “They only had enough time to get their gear out in the water, barely make a trip, and then they had to stack out again.”

And this wasn’t just any year. Cobban Jr. knew January 2020 could be the last season of the derby-style cod shery, before the shery transition to a proposed individual shing quota management system, Gribble testi ed. Those nal days of the old shery would be critical to establish vessel catch history, and in turn future IFQ shares.

“We were already a day or two late, so it was really important for us to get to the grounds,” Gribble told the board.

The added scramble to secure shing history before rationalization can create unintended consequences in eliminating the race to sh.

Lincoln, Commercial Fishing Safety Research and Design Program director for NIOSH, showed a spike in Bering Sea/Aleutian Islands crab eet fatalities in the 2004-05 season, the year before the shery was rationalized, with the loss of the Big Valley in January 2005.

“When creating or modifying shery management policies, policy makers should consider the potential safety repercussions of those policies and make e orts to enact policies to mitigate these hazards,” Lincoln testi ed.

During testimony on Thursday, March 4, Scandies Rose majority owner Dan Mattsen denied that building cod

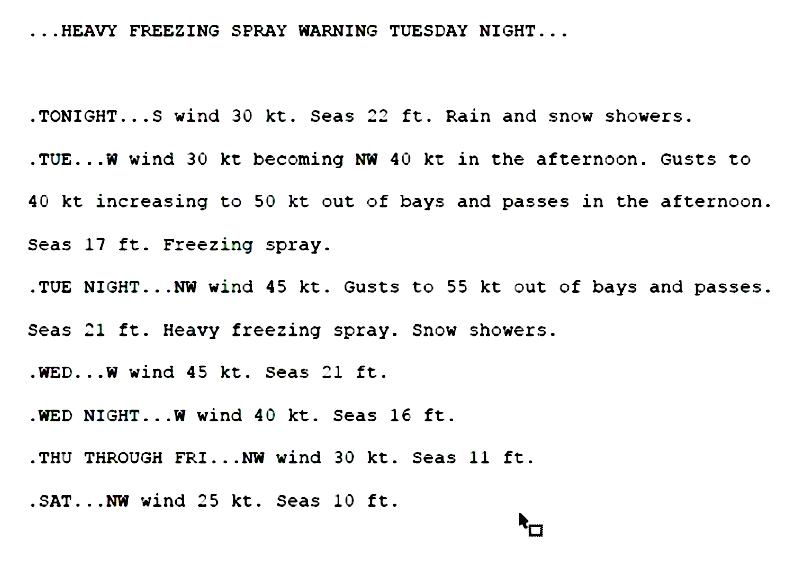

Marine forecast the night of departure.

catch was part of their shing plan but added that Cobban Jr. had autonomy over the vessel as a 30 percent owner.

“Gary had much more experience than I did as a captain,” Mattsen testi ed. “I would never second-guess Gary’s decision making. I would just trust that he would do the best for himself, for the boat, and for the crew.”

Mattsen’s second round of testimony before the board of investigation on March 4 followed testimony from naval architect Bruce Culver, who completed the last stability report for the Scandies Rose in April 2019.

A naval architect from the Coast Guard’s Marine Safety Center found Culver’s stability report contained “signi cant errors and omissions,” in particular regarding stability criteria and down ooding points.

Culver, who said he has provided more than 200 stability reports in his 30-year career, defended his work, and Mattsen refused to blame him.

“It’s for other engineers to judge the quality of the work. I’m not throwing Mr. Culver under the bus. I’m a sherman,” Mattsen said.

However, Mattsen’s prior testimony on the rst day of the hearings revealed that he hired Hal Hockema to do the stability test on another of his vessels. Barton Barnum of the NTSB asked why he had hired a di erent naval architect.

“Excuse my French, but my fucking boat sank,” Mattsen testi ed. “So I wasn’t going to go back to the same naval architect until we found out what the hell was the cause of that.”

But the ice, the weather and

Jessica Hathaway

Scandies majority owner, Dan Mattsen.

the stability report weren’t the only question marks in the Scandies Rose’s seaworthiness that night.

Though the boat was known for being well maintained, the crew documented a recurring issue with the starboard bycatch chute, which had been repaired twice that year — the second time right before the season after a failed repair at the dock in Seattle, which Mattsen referred to as “a cluster.”

The crew found it was still leaking while they were getting ready for the upcoming season and agged it for repairs.

“There’s a void underneath [the starboard crab waste disposal chute] from the forepeak to the engine room, and Gary [Cobban] noticed there was water in it,” Mattsen testi ed. “It turned out to be a crappy weld job. So they had it redone before the winter crab season.”

They hired Highmark Marine Fabrication in Kodiak, where welder Jordan Young did the work. He said the previous xes on the chute had not rooted out the corrosion.

“They did a doubler, so they didn’t replace the wasted metal, they just put a patch over the top of it,” Young testi ed, referring to the patch job done in Seattle. “There was signi cant wasting, and my job was to cut it out, get down to solid metal, and install all new material.”

Kerry Walsh, the project manager for Global Diving and Salvage, led a team that surveyed the wreckage in February 2020.

“Before we left the dock, it was obvious there were questions about the fabrication work that went down prior to the ship sailing,” Walsh testi ed.

His team sent a Falcon ROV to take images and video of the wreckage, but Walsh said the vessel was on its starboard side, and they could not access the chute.

“There is no obvious reason, no obvious sign why it went down in our eyes,” he said.

Following the welding work in Kodiak, the Scandies Rose crew was set to make its way to Dutch Harbor on Dec. 30, 2019. The trip had begun after three days of nonstop gear work, according to Lawler. They were bustling to switch the pots for the pot-cod season before they moved on to catching opies.

“A typical day on the Scandies was 20 hours. Most days we would run and haul gear for 20 hours and then take a six-hour nap,” testi ed Cory Fanning, a former engineer on the Scandies Rose. “Gary worked hard. The crew worked. He maybe pushed too hard sometimes. He wanted to be the best at what he did, whatever that was. And maybe at times that didn’t make the crew so happy, but he was an incredible sherman.”

USCG evidence

The fatigue caused by the race to sh is one of the big drivers for quota implementation. Ultimately, crab rationalization reduced disasters signi cantly, Lincoln testi ed. However, meeting delivery deadlines to processors (scheduling deliveries avoids a ood of product, but also creates pressure to meet the deadline) and minimizing days at sea to reduce operating costs still leads to long days on deck.

“Rationalization provides the ability to err on the side of safety. Nobody else is going to catch your sh, so that buys you time,” Woodley told NF. “But there are still other operation pressures, which are going to cost you money.”

Lincoln also acknowledged the operating costs of reducing fatigue and noted that the biggest hurdle may be the cultural perception of sleep being a luxury to be bypassed when working hard.

“It would be great to overcome the

Jennifer Lincoln/NIOSH

The tactical advantages of a rested crew.

culture that sleep is for the weak and instead embrace the culture that somehow sleep is a tactical advantage,” she testi ed.

“We have to manage risk. The more fatigued someone is, the more other safety measures should be put in place,” Lincoln added. “What controls should be put in place around the wheel watch? What controls need to be put in place around gear handling when you’re fatigued?”

In the same presentation, NIOSH epidemiologist Samantha Case testi ed that weather had been a signi cant contributing factor in Alaska shing fatalities. In the Bering Sea, survival depends on getting out of the water quickly, and heavy weather can be the di erence between getting in a survival suit or not and then into a life raft or not.

Lawler testi ed that he thought between the crew being tired after gearwork in Kodiak and the forecast, they’d leave the next day.

“You know we’d been working our asses o getting the boat ready. And then we heard the weather forecast. And I’m thinking, ‘Oh, the boys are gonna have a bar night. We’re gonna go into town and get some beers because we’re de nitely not leaving in that.’”

He remembered Cobban Jr. warning the crew about the weather they were heading into and to ensure the gear was secure on deck.

BRI DWYER PHOTO

CONNECTED

The largest commercial marine trade show on the West Coast, serving commercial mariners from Alaska to California returns in the Fall of 2021.

fALL 2021 | Seattle, WA

Lumen Field Event Center

Presented by: Produced by:

Look for the Pacific Marine Expo Official Date Announcement this Spring and sign up for Expo updates at pacificmarineexpo.com

Become a Coast Guard Approved Marine Safety Instructor!

AMSEA is recruiting commercial fishermen in the U.S. Southeast, Gulf of Mexico, and Alaska, to become Marine Safety Instructors.

Learn to teach Fishing Vessel Drill Conductor and Vessel Stability classes that meet U.S. Coast Guard training requirements for commercial fishermen. Training costs only $995 and patial scholarships are available for qualifying commercial fishermen. Learn how to become an AMSEA instructor at www.amsea.org or call (907) 747-3287.

Help commercial fishermen survive emergenices at sea.

Between the implementation of stability checks in 1999 and Bering Sea quota implementation in 2005, the only vessel sinking occurred the season before rationalization/quotas began.

“I knew we were leaving into a storm, and it just didn’t feel right,” Lawler said. “Nothing about it felt right.”

Daniel DeLaurentis, captain of the F/V Ru & Reddy, had anchored in the lee of an island early the next morning, on Dec. 31, 2019. That evening, a satellite phone call from their company dispatcher alerted them that the Coast Guard was requesting help after hearing a mayday radio call at 10 p.m. from the Scandies Rose, 28 miles away.

DeLaurentis testi ed that he had to decline.

“I could not travel with a load of gear” in those conditions, he said.

Mike Barcott, attorney for the vessel owners, encouraged the study of the human factors, decision-making that led to vessel loss.

“Let me characterize something I see in these ve events — and there may be others,” Barcott said in response to Lincoln and Case’s presentation at the hearings.

“St. George — good captain, good boat, in icing — capsized.

Northwest Mariner — highliner, good captain, icing, capsized.

Lynn J — good captain, good boat, icing, capsized.

Destination — good captain, good boat, icing, capsized.

And now Scandies Rose, by all accounts a very good boat and a very good captain.” “There has to be some investigation into the pattern of all of them,” Lincoln replied. “And if some of our underlying assumptions aren’t valid, then adjustments should be made.” Former Coast Guard rescue swimmer and maritime safety expert Mario Vittone testi ed on the importance of proper safety gear and drills, as well as some possible changes to required safety gear. He noted that ares are practically useless as safety equipment. “I would trade every are on my boat for three waterproof ashlights,” he testi ed. Vittone advised being sure you have a survival suit that ts and training with your speci c raft. “There is a need to go back and evaluate the usefulness of this gear and how drills are done,” Woodley told NF. “Fishing vessel safety requirements and regulations are pretty darn good. But captains and crews really need to think outside the box and be creative. It isn’t enough to stand around in the wheelhouse and put on a suit. You have to run drills as if an actual emergency is occurring. Your heart needs to be racing — you need to feel pressure. Getting to that level requires more of a cultural change than a regulatory change.”

Woodley remembered his time as a safety inspector with the Coast Guard, making changes to drill oversight requirements after the freezer-longliner Galaxy sinking in 2002. The change, he said, dramatically improved drill quality in the eet.

“What the Coast Guard pays attention to is the stu the captain is going to prioritize,” Woodley told NF. “So if the Coast Guard comes onboard and wants to see your drills, you’re going to pay attention to that.”

Nothing will ever eliminate the risk of shing in the dark, cold and isolated waters of the Alaska winter shery, Lincoln testi ed.

“It’s crab shing in the Bering Sea,” testi ed Bryce Buholm, most recently master of the Western Mariner. “It’s not safe. We do what we’ve got to do.”

Buholm testi ed the Scandies Rose was the rst house-aft vessel to roll over in the shery. No matter what you do, you’re still shing in the Bering Sea.

“I call it the freezer hold of hell,” Buholm testi ed.

Still, the loss of the Scandies Rose was a shock, as was the Destination before it. The conclusion is yet to come. The Coast Guard and NTSB are expected to publish separate reports on the accident and loss, following the testimony and evidence provided in the hearings.

So for now, the eet is still shing, waiting for the reports, recommendations and possibly a new slate of regulations aimed at improving safety and outcomes for our shermen who work some of the harshest grounds in the world.

Jeff Pond

The loss of the Destination in 2017 inspired many new stability assessments in Alaska’s Bering Sea crab eet. Jessica Hathaway is the editor in chief of National Fisherman.