8 minute read

Marshall Cassidy, Hall of Fame Class of 2022

An Innovative Spirit

Marshall Cassidy dedicated 60 years to racing, making the sport better through innovation and refinement of methods

BY EDWARD L. BOWEN

Chairman, Hall of Fame Nominating Committee

The life and times of Marshall Cassidy had a hint of similarities to Teddy Roosevelt’s career. Like the 26th President, Cassidy was a vigorous outdoorsman with wide-ranging interests yet eventually operated from within the milieu of formal offices. Throughout the years, Cassidy created or helped create a sequence of innovations which still contribute to thoroughbred racing. They include the modern-style starting gate, the photo finish, medication testing, prerace veterinary exams, electronic timing, and the pivotal film patrol to help stewards police race riding. The latter portions of his career saw his contributions made from the aura of The Jockey Club offices and board room of the New York Racing Association.

For all the visibility that such improvements brought to him personally, when Cassidy looked back on his career he gave full credit to others. Beginning a 12-part series of Recollections for The BloodHorse in 1967, Cassidy wrote: “Those actually deserving the credit were the wonderful men for whom I worked. They not only permitted me to make changes, but furnished the money necessary for the projects, and all the final decisions were dependent on them.”

The son of race starter Mars Cassidy, Marshall Cassidy was born in Washington, D.C., in 1892. He rode flat runners and steeplechasers in amateur races from New York to Mexico and plied the starter’s role himself. He also served as groom, blacksmith, and steward.

The evolution to the modern starting gate involved a progression of various contraptions to address the difficulties of getting a field of milling thoroughbreds off to a relatively even start. Cassidy and various others had input. Later, Cassidy’s positions in racing gave his thought processes additional influence.

One of the other improvements was described in detail by Cassidy in Recollections and serves as an example of what the New York Times described after his death as “passionate honesty, indefatigable energy, and fertile imagination.”

Cassidy wrote that when he was an assistant starter for this father prior to World War I, he would walk to where he could watch the finish of races when a race’s distance made that possible. “The judge’s stand in those days was on the ground, or near ground level, and the judges sighted across the track to the finish post on the inside rail to determine the placing of the horses as they passed the post.” Because he had no official responsibility once the race was started, he could watch finishes from different vantage points. “It did not take me long to realize that the judges’ order of finish was not always correct. As a matter of fact, one day at Saratoga I saw a horse on the extreme outside rail win by a full length yet was not placed among the first three by the judges.”

In 1921, Cassidy became a starter on his own, working Canadian tracks during the summer and at Tijuana in Mexico during the winter. Just being in Mexico conjured memories of a bizarre chapter. For all the seeming dedication to horse racing, Marshall Cassidy — again like Teddy Roosevelt — had other interests. They included gaining a transport pilot’s license and a deep-sea diver’s license. In the decade before that Canada/ Tijuana arrangement, he had studied during an earlier stint in Mexico to become a mining engineer. The location and time destined him to an adventure he clearly could have done without. What was known as the “Madera Revolution” broke out. Cassidy and some other United States citizens were making their way to the United States via a pedal-operated little “hand car,” as described by the New York Times. The device was dynamited by one of the rival factions, a happening that pushed Cassidy to the side of Pancho Villa. He served with Villa’s army for several months “with some reluctance,” noted the Times.

When life’s twists and turns enabled Cassidy again to turn his attention to such matters as racetracks’ placing judges, he mulled the situation and tried various ideas without a breakthrough moment. Then one day he must have contrived to leave the start to his crew, for he watched a race from the grandstand roof.

“Right then I realized that if the judges were moved to the roof and a

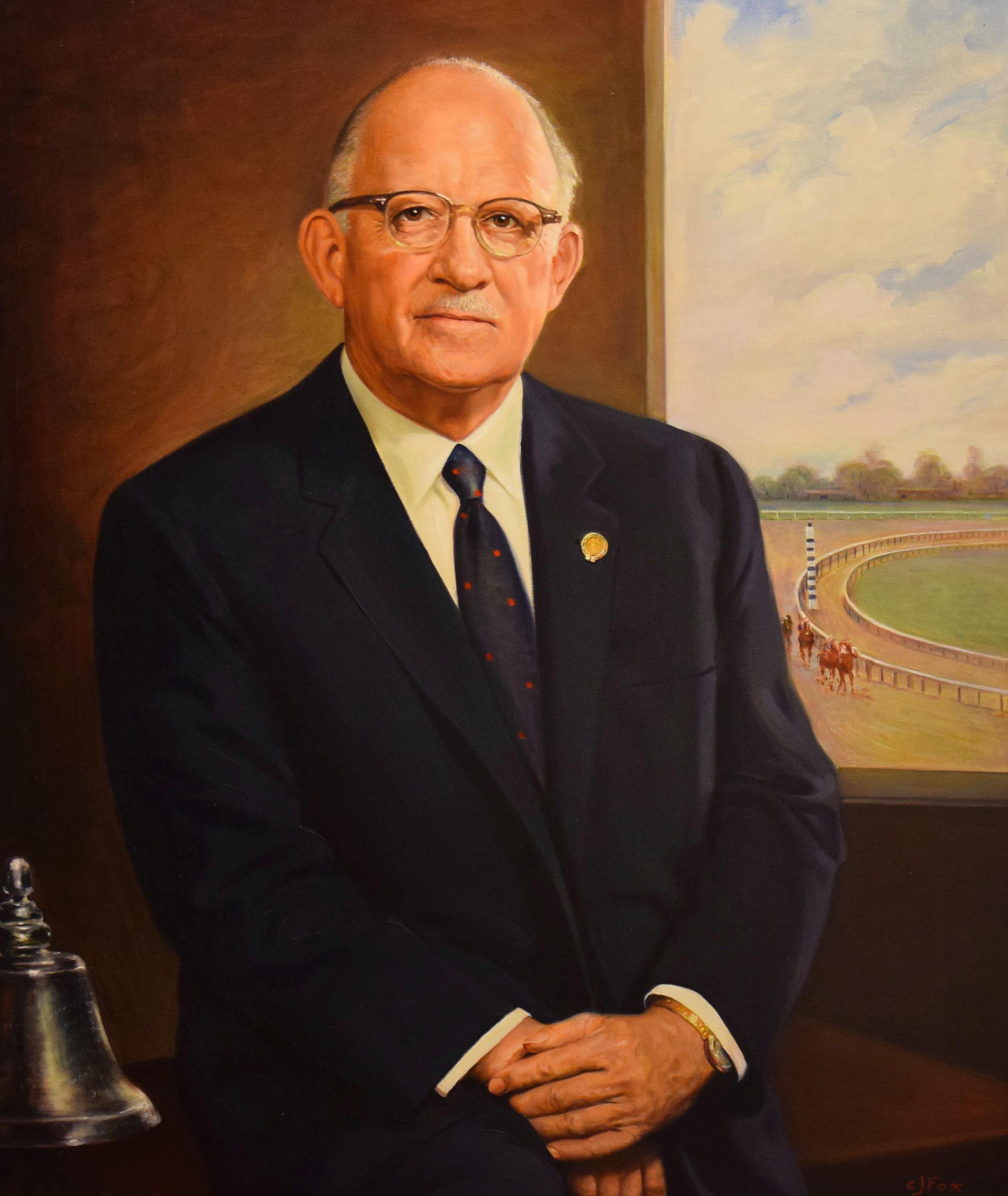

Above: Marshall Cassidy, shown here in a painting by Charles J. Fox that was gifted to the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame by George D. Widener, served as executive secretary for The Jockey Club from 1945 through 1964.

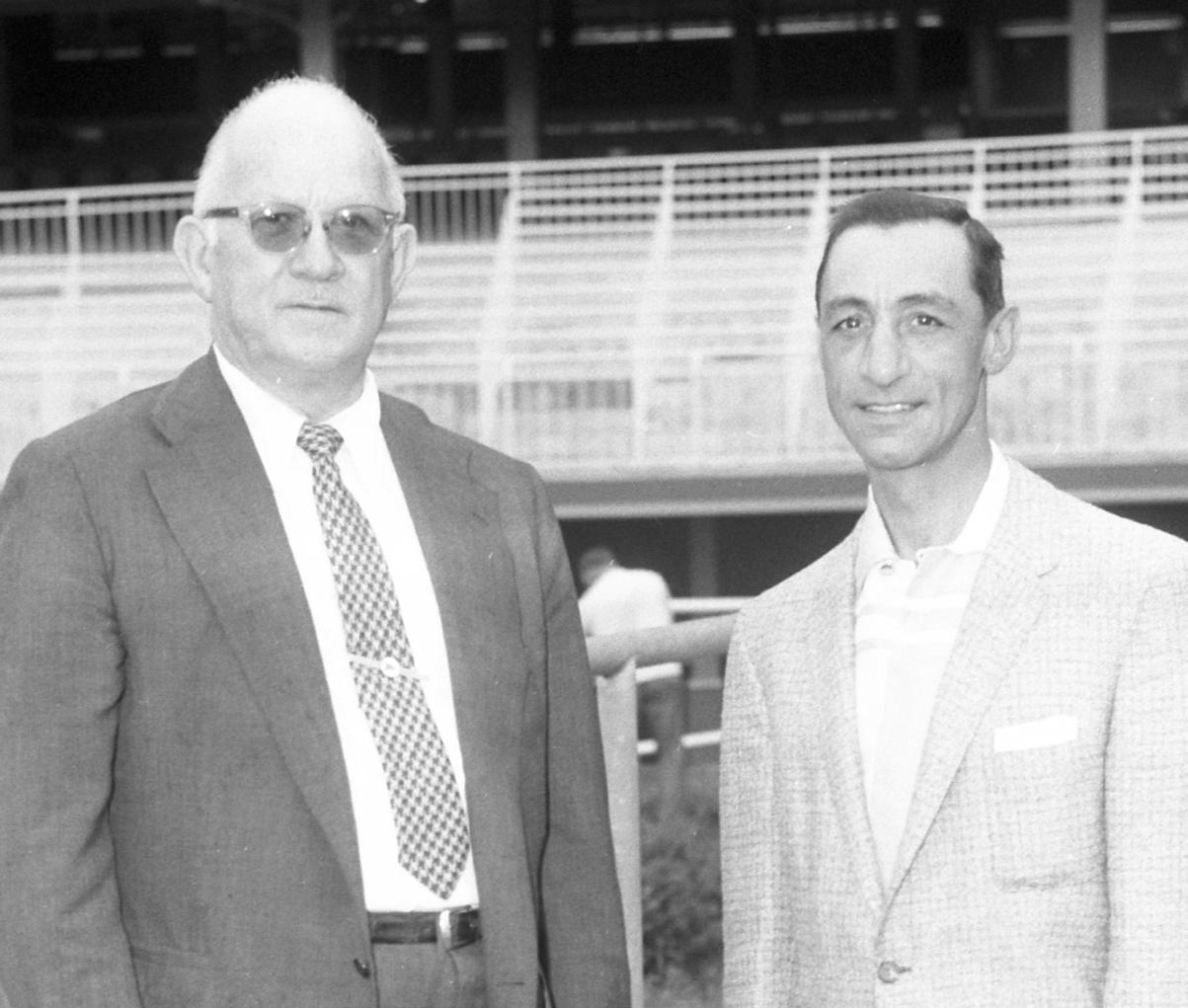

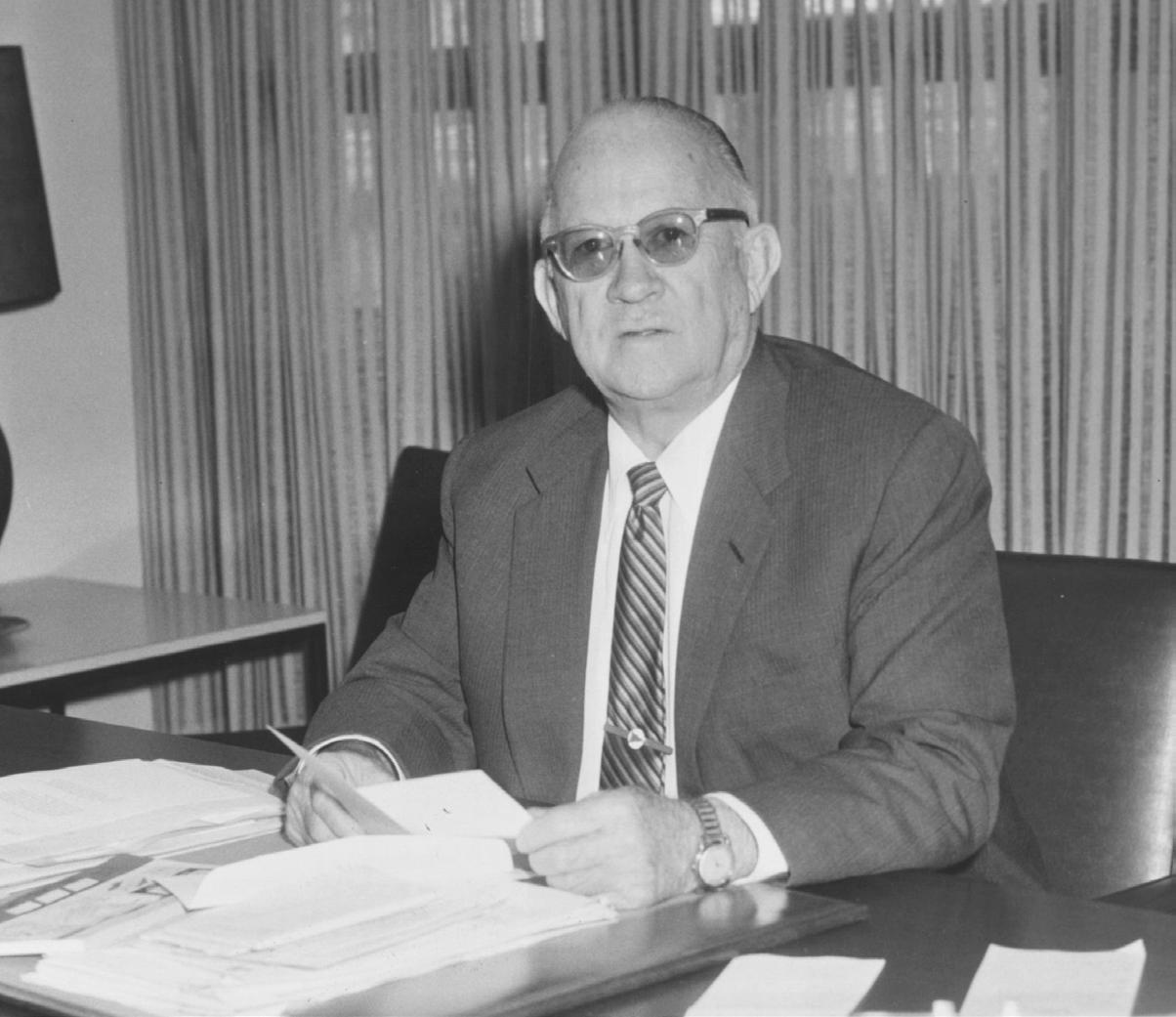

Above: Marshall Cassidy, on right, is pictured with his father, longtime race starter Mars Cassidy. Opposite page top: Cassidy and Eddie Arcaro at Aqueduct. Opposite page bottom: Cassidy is pictured in his office at Aqueduct, 1959.

finish wire were placed over the track proper, the judges’ ability to see the finish would be improved 99 percent,” he recalled. Track management was not receptive to such a major change.

It was some years later that he became involved in the design of a racetrack for Agua Caliente, also in Mexico. Cassidy produced permanent starting stalls, positioned where nine chutes led into the track from different positions to accommodate various lengths of races. He also planned to place the judges’ stand on the grandstand roof and install the finishing wire he had imagined.

Still, those track owners, too, feared the idea too radical and not long before he had completed construction he was told he would not be allowed to implement the change. Flash forward to 1933, and Cassidy was appointed a steward at Hialeah, having resigned from Caliente. Hialeah had come under leadership of Joseph E. Widener, whose vision for an elegant palace of sport in tourist-rich Southeast Florida was to be enhanced by Cassidy’s imagination as well as his own.

Widener gave Cassidy plenty of leeway. In addition to being able — finally — to give the placing judges a raised, and enhanced, view, Cassidy “made headway on the photographing of race finishes.” After the Hialeah winter season, racing returned in the spring to New York’s Belmont Park, where Widener was also president. “The camera and developing rooms, as well as rooms for the placing judges and stewards, were built on top of the grandstand.”

Those changes paved the way for Cassidy to continue refining the ideas. They led to a pair of developments which eventually would become part of the DNA of modern horse racing: The photo finish camera, to determine the order of finish with precision, and, thence to the film patrol. The conduct of fair race riding suddenly had impetus, and those watching (stewards) had authority to disqualify horses and impose financial penalties and suspensions on jockeys. In Recollections, Cassidy harked back to the great jockey Eddie Arcaro commenting in his book I Ride to Win, that “If I were asked what I considered the greatest boon to racing in the years I’ve been in it, I would have to cast my vote for the film patrol.”

Also in Florida in the 1930s, Cassidy recalled, Widener personally financed sending a racetrack veterinarian and a chemist to Europe to study France’s nascent system of saliva testing. The testing was done to detect illegal substances in horses. The system was impressive enough that Dr. J. G. Catlett was put in charge of conducting saliva tests at Hialeah, a crucial step in the ongoing progression to combat efforts to affect race results via medications.

Cassidy was cognizant that any activity involving gambling and large sums of money would summon bad apples. One nefarious practice was

— MARSHALL CASSIDY

substituting a faster horse for a slower one. He had been deft enough to spot a few ringers during his days as a starter in the 1920s. He had not discerned tiny differences in appearance, but a horse’s mannerisms before the start alerted Cassidy that he was not actually the horse he was entered to be. That stayed in his mind, and he was later involved in the steps leading to the lip tattoo to identify horses.

Cassidy’s involvement in organizational leadership roles grew throughout the years. He became assistant secretary and assistant treasurer of The Jockey Club in 1942, when William Woodward, Sr. was chairman, and was executive secretary for that organization from 1945 through 1964. For some years, Cassidy also served director of racing for the New York Racing Association. During those years, Cassidy started The Jockey Club’s school for race officials and a school for jockeys. He also supervised the Stud Book and founded The Jockey Club Round Table Conference.

A member of Joseph E. Widener’s family, George D. Widener, was chairman of The Jockey Club at the time Cassidy sought to retire, in 1963. Widener was stepping down as chairman, so he prevailed on Cassidy to stay on to assist the incoming chairman, Ogden Phipps. The following year, Phipps expressed his appreciation for Cassidy’s assistance during the early phase of his chairmanship. He said, “Mr. Cassidy has acted as our ambassador to foreign countries and to the National Association of State Racing Commissioners.”

Cassidy died four years later, in 1968. His reputation, as Phipps noted, was international. Maj. John Nethersole, who served England’s Jockey Club as course inspector and later as Stipendiary Steward, once remarked, “The executive secretary of The (U.S.) Jockey Club is the most respected, knowledgeable, and best-known man in racing circles throughout the world.”

MARSHALL CASSIDY

Born: Feb. 21, 1892, Washington, D.C. Died: Oct. 23, 1968, Glen Cove, New York

Achievements: • Developed the modern starting gate, the photo finish camera, and film patrol, among many innovations • Executive Secretary of The Jockey Club 1945 through 1964 • Established The Jockey Club Round Table Conference • Served as NYRA Director of Racing • Thoroughbred Club of America’s Honored Guest 1957