“THE LEGENDARY BURN ON THE MCCASH WAS A BRIGHT SPOT IN THE DARK.”

Kelly Ramsey on fighting fire with fire on the Klamath National Forest FUEL FOR THOUGHT

The technology that could help manage highly flammable Great Plains red cedars BEYOND BORDERS

The unique funding model treating forests across boundaries in central Colorado

SUMMER/FALL 2024 THE MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL FOREST FOUNDATION

AGENT OF CHANGE

The path of a wildfire is shaped by vegetation, topography, and weather.

Its physical path is not unlike the one it has traced through human history. For millennia, wildfires were part of the natural world. As forests ignited, undergrowths cleared and biodiversity flourished. This harmony was encouraged by centuries of Indigenous cultural burning.

With colonization came differing attitudes toward forests and their resources. Those attitudes coalesced after the Great Fire of 1910, a devastating event that scorched three million acres across the Northern Rockies. Much of the fire occurred on lands managed by the newly established Forest Service.

The U.S. Forest Service, just five years old at the time, was given an additional purpose: to suppress fire at all costs. Over one hundred years of fire suppression has caused fuel-laden forests to burn hot and bright.

Now we fight to restore balance through collaboration, adaptation, and an understanding that destruction and renewal are cyclical, not antithetical.

This issue of Light & Seed is an exploration of our everevolving relationship to wildfire. From technological advances to frontline experiences, these stories capture how there’s never been more potential—and more at stake—in tending to the fiery forces that sustain forests and grasslands and the communities that rely on them.

Lolo National Forest, Montana

Photo by the U.S. Forest Service

CONNECTIONS

Want to dig deeper into the content? Visit nationalforests.org/connections to listen, watch, and read more about the articles in this issue.

Learn more about the individuals featured in “Heard in the Woods” on page 30. Listen to firefighter Frank Lake discuss fire ecology and Indigenous knowledge in an episode of the podcast Good Fire, read fire advisor Lenya Quinn-Davidson’s essay “Seeing the Fish for the Fire,” and dig into a report Jonathan Coop co-authored about using prescribed burns for wilderness fire management.

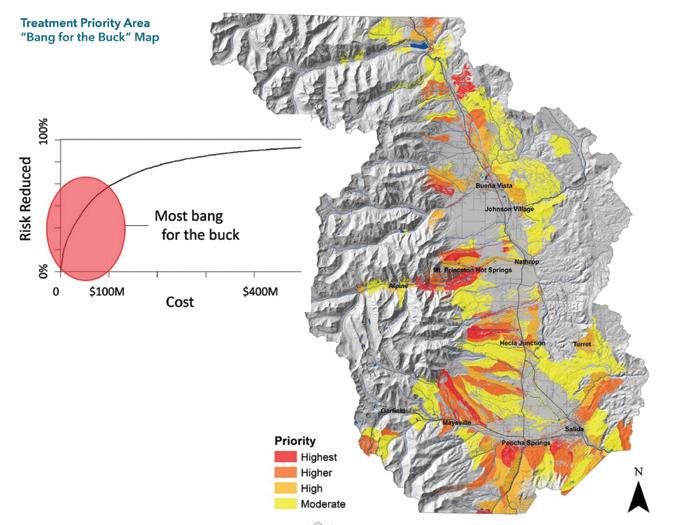

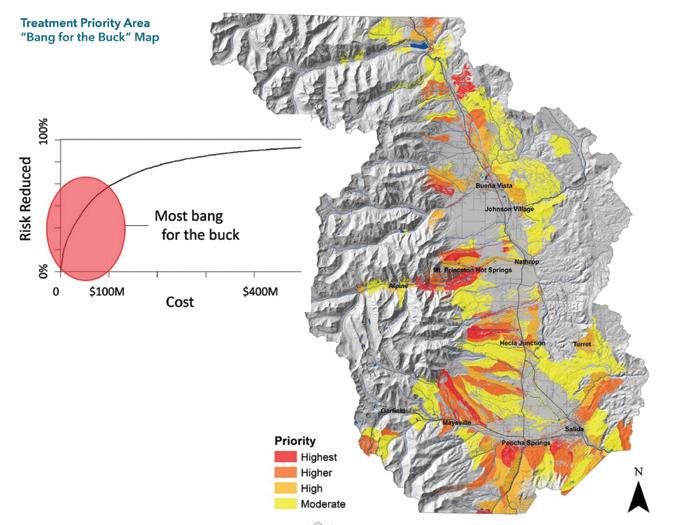

Explore the “Chaffee County Community Wildfire Protection Plan,” an initiative that informs how funding managed by the National Forest Foundation’s Upper Arkansas Forest Fund is distributed, as reported on page 24.

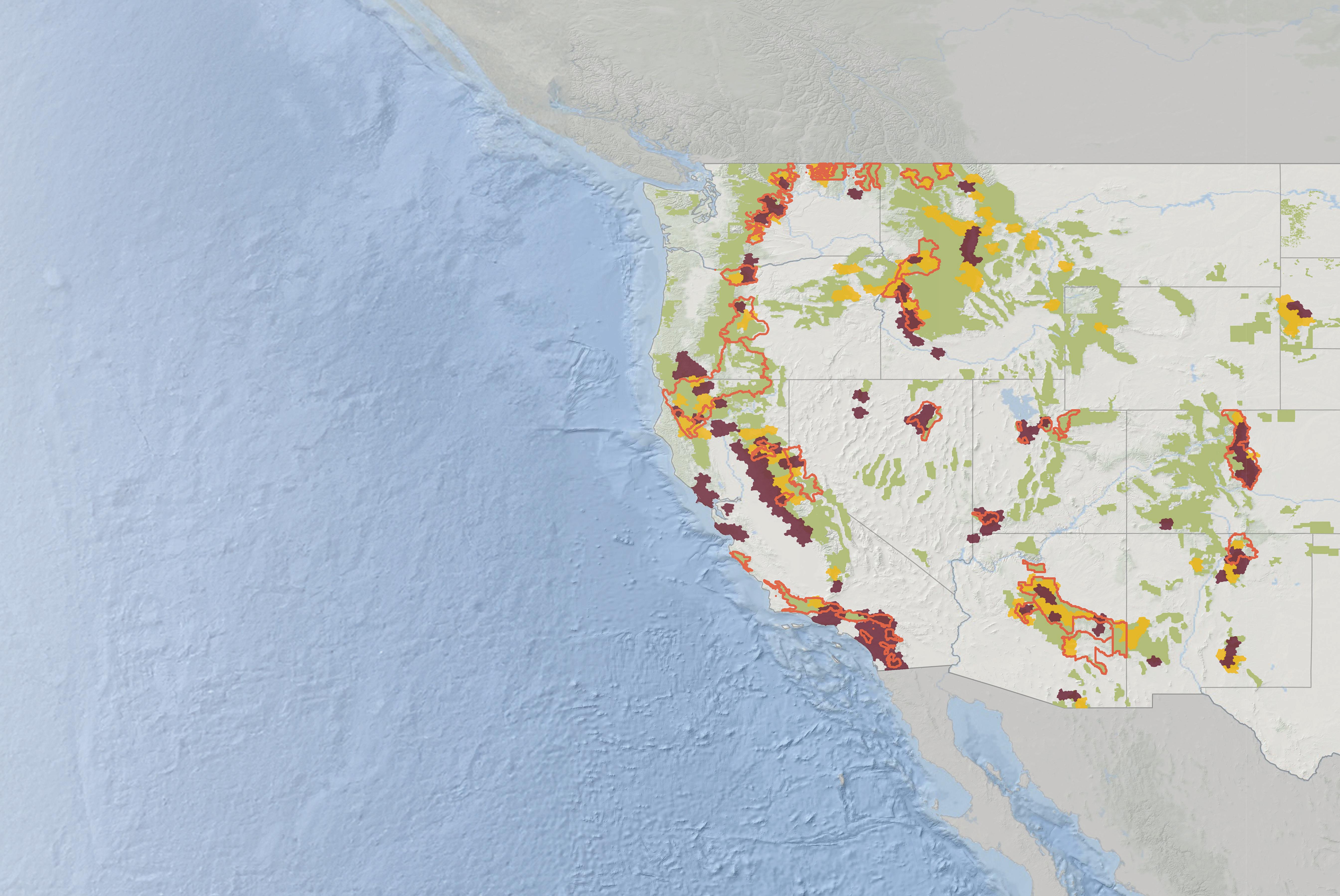

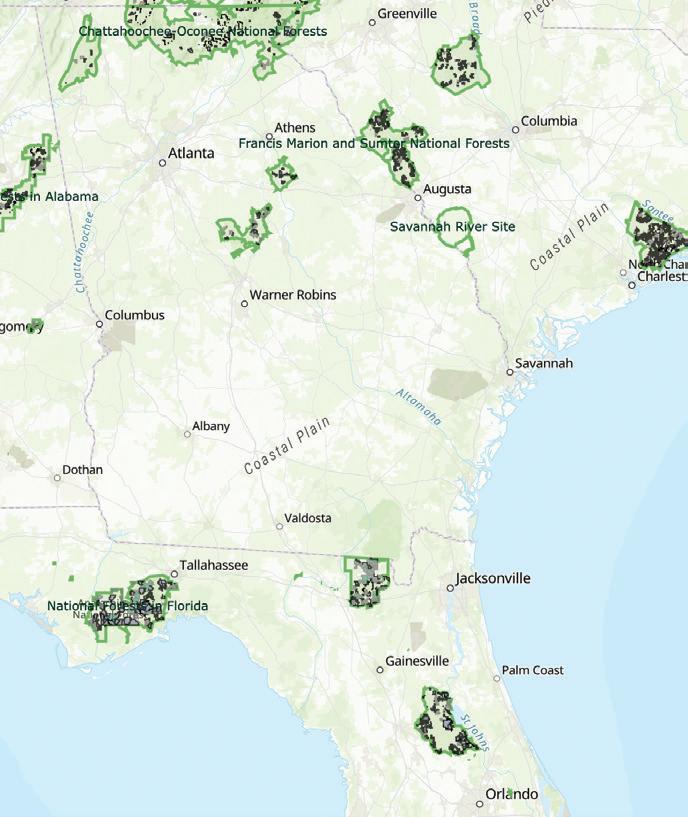

Dive into the U.S. Forest Service’s “Wildfire Crisis Strategy” to learn more about how the agency plans to work across property boundaries to protect communities from wildfire, as illustrated on page 32.

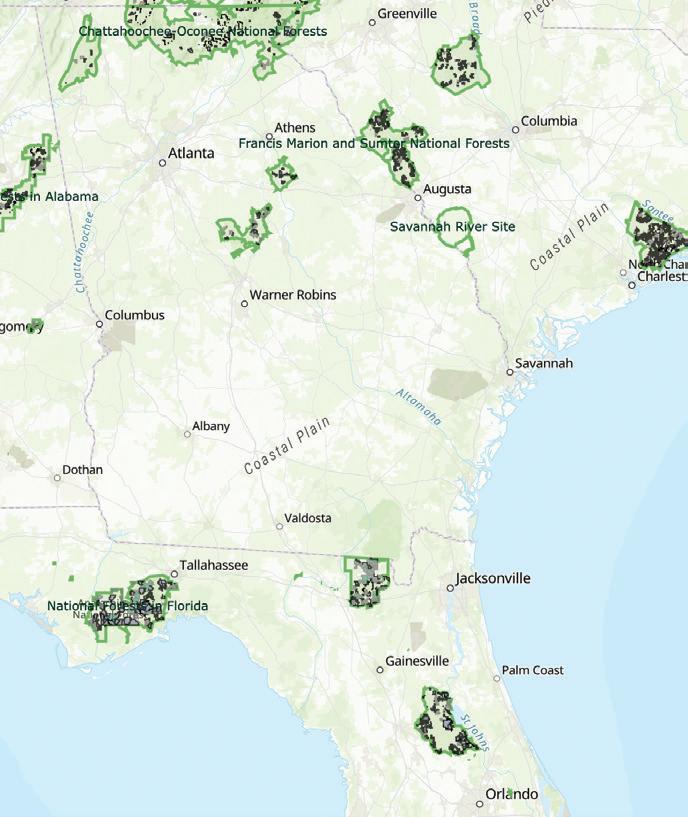

Check out the U.S. Forest Service’s prescribedfire tracker showing planned, current, and completed burns across the Southern Region, which is overseen by Ed Hunter, a Deputy Regional Forester featured in “People of Public Lands” on page 12.

Listen to Life with Fire, a favorite podcast of writer and former hotshot Kelly Ramsey, who chronicles her experiences battling wildfire in Northern California on page 14. Start with episode 32, “A Life of Fire as a Trans Woman,” which features Bobbie Scopa, who spent 45 years as a firefighter, including close to a decade as Assistant Fire Director for the U.S. Forest Service.

Watch Margo Robbins, featured in “People of Public Lands” on page 10, in the 2023 documentary Elemental: Reimagine Wildfire, narrated by actor David Oyelowo. The film, available on Apple TV, interrogates our relationship with fire in the face of climate change through the perspectives of fire survivors, climate experts, and Indigenous peoples.

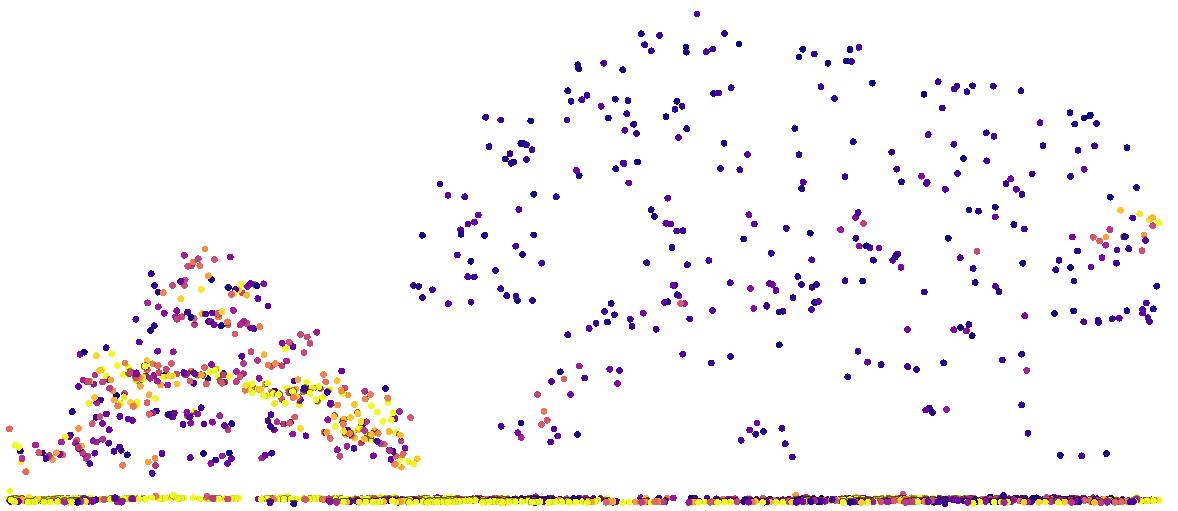

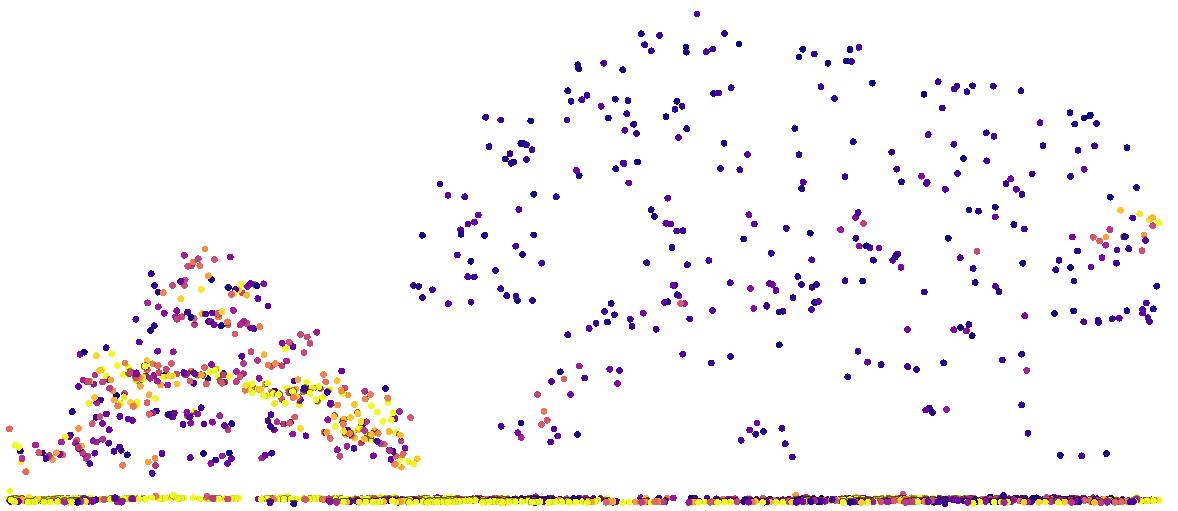

View interactive maps created by researchers at Colorado State University that show the encroachment of Eastern red cedar, a dangerous fuel source, in Nebraska. The maps are based on data collected using LIDAR, an innovative technology that writer Morgan O’Hanlon examines on page 20.

2 LIGHT & SEED

Photo by the U.S. Forest Service

by Emily

People of Public Lands: 10 Margo Robbins People of Public Lands: 12 Ed Hunter Journeys: 14 Holding the Line The Response: 20 Finding the Fuel NFF Field Report: 24 A Fire Knows No Bounds Heard in the Woods 30 The Last Word: 32 Meeting the Moment TABLE OF CONTENTS 14 24

Cover photo by Kelly Ramsey

Photo by Kelly Ramsey

Photo by Claire Brown

Photo

Lord

10 3 LIGHT & SEED

Photo by Tell M. Deatrich

The Good Fight

Kelly Ramsey lights a prescribed burn in Northern California’s Six Rivers National Forest, where she was stationed as a hotshot for two seasons.

In her cinematic essay “Holding the Line,” Ramsey takes us to the frontlines of the 2020 McCash Fire as it threatens her home, Happy Camp, a town of 1,000 people.

As her team is tasked with lighting an immense backburn to stop the encroaching flames, Ramsey battles with the reality of her role in the fight: “I reminded myself that we sacrificed these acres to save the thousands, maybe millions, of acres at our backs. This wall of Roman candles was, in a sense, good fire.”

Read the full story on page 14.

Photo by Kelly Ramsey

Photo by Kelly Ramsey

A Tide to Stem

Crews patrol mow lines during prescribedburn operations to control Eastern red cedar encroachment and increase grassland resilience in the Bessey Ranger District of Nebraska National Forest.

Across the Great Plains, the spread of highly flammable red cedar is increasing wildfire risk.

Although public-land managers and volunteer groups are working on managing the species’ proliferation through controlled burns, it’s difficult to concentrate efforts due to the spread of the trees on remote and private land.

But that may soon change thanks to LIDAR, a data-collection technology that researchers at Colorado State University are using to create maps that track early encroachment.

Writer Morgan O’Hanlon reports on how this technology could benefit private landowners, public-land managers, and the dozen or so prescribed-burn associations operating in Nebraska.

“It doesn’t take anything to kill a threeto four-inch tree,” said Tell Deatrich, a rancher and member of the Loess Canyons Rangeland Alliance.

Read the full story on page 20.

Photo by Gregory Wright, courtesy of the U.S. Forest Service

A Boundless Bond

A tractor performs forest thinning in Central Colorado’s San Isabel National Forest, where the National Forest Foundation is set to deliver fuel-reduction treatments to up to 50,000 acres by 2033.

That’s being made possible through the Upper Arkansas Forest Fund, an innovative funding model that enables the NFF to pull support from various sources to facilitate wildfire-mitigation work.

Much of this work is taking place across both private and public lands, requiring a level of collaboration that Matt Nykiel, the NFF’s Central Colorado Project Coordinator, believes is crucial to ensuring greater forest health.

“To do this effectively means landowners have to take a more active and responsible role in stewarding the ecosystem in concert with their publicland neighbors,” said Nykiel.

Read the full story on page 24.

Photo by Kellon Spencer

Photo by Kellon Spencer

REVIVING ROOTS

How Margo Robbins is leading her community, the Yurok Tribe in Northern California, and other Indigenous groups in reclaiming their fire-dependent cultures.

INTERVIEW BY ERIN VIVID RILEY

When Margo Robbins was growing up on the Upper Yurok Reservation along the lower Klamath River, she listened to elders speak about how their ancestral homelands shifted from large swaths of prairie to dense forests of fir. For hundreds of generations, the Yurok would practice cultural burning, using controlled burns to maintain the health of their lands. After fire-suppression policies were introduced in the 1800s, that way of life changed.

In 2013, Robbins created the Cultural Fire Management Council, a community-based nonprofit composed mostly of tribal members that works to restore the Yurok’s homelands. Two years later, she helped launch the Indigenous Peoples Burning Network—along with The Nature Conservancy and practitioners from the Hupa and Karuk Tribes—in order to help other groups create similar programs. We talked to Robbins about how her ancestral homelands and cultural practices have transformed alongside fire policy.

Can you describe how your home has changed? I have always lived here on the Upper Yurok Reservation, except when I went to college. When I look out my window, I can see the river, and beyond it, a traditional village site that at one time was a big flat grassland. But now, it’s just full of brush and trees. Our landscape is very, very different than when I grew up because of the fire-exclusion area.

PEOPLE OF PUBLIC LANDS 10 LIGHT & SEED

Robbins uses cultural burning to restore her homelands. Photo by Matt Mais

One of the big reasons why we burn and continue to burn is for our basket-weaving materials.”

Was cultural burning a part of your upbringing?

When I was very young, there was a period of time in the ‘60s when the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire) and the U.S. Forest Service realized the benefits of fire, and they actually helped people burn. Then it became a very serious offense. Grandmothers would sometimes send their grandsons up a hill with a pack of matches because little kids can run through the mountains like nobody’s business and escape people who might otherwise arrest an adult. But cultural fire was not really part of my upbringing.

Which important plants rely on burning?

One of the big reasons why we burn and continue to burn is for our basket-weaving materials. Hazel and bear grass are fire-dependent; others rely on fire to thrive. Then you have the tanoak tree, which produces the kind of acorn we like to eat. If they aren’t burned underneath, then the acorns get really buggy. Those that take root grow into tall skinny trees that don’t produce anything. They also create a closed canopy that keeps sunshine from getting to huckleberry bushes.

What is the Cultural Fire Management Council (CFMC) currently focusing on?

We used to have elk here when the area was almost 50 percent prairie. We only have two percent of that left. The elk are just a few ridges over, so we have plans to create a corridor and extend the prairie, which is really encroached on with fir trees, Himalaya, and Scotch broom.

What are the challenges facing your work?

One of the challenges to continue this type of work is a steady source of funding. The CFMC got its first big grant from CalFire and it made a big change in our landscape. The Forest Service owns a pretty good-sized piece of Yurok ancestral territory. We’re just in the beginning stages of partnering with them to take care of a smaller piece of overlapping land. We are also required to get a permit to burn on fee and trust land from CalFire and the Bureau of Indian Affairs. I feel like it should be the tribes who are the ones deciding when and where we can burn. Who knows our homeland better than us?

Learn more about Robbins’ work with the Cultural Fire Management Council at culturalfire.org and with the Indigenous Peoples Burning Network at firenetworks.org/ipbn.

Attend a training exchange hosted by Robbins and the Cultural Fire Management Council. The biannual meetings, geared towards fire practitioners of all levels, focuses on sharing information about the role of fire on the ecosystem, Yurok culture, and prescribed burns.

Photo by Elizabeth Azzuz

Robbins giving a basket demonstration at the Cultural Burn Training Exchange; right, Robbins leading a burn

11 PEOPLE OF PUBLIC LANDS

Photo by Elizabeth Azzuz

BLAZING A TRAIL

As a newly appointed Deputy Regional Forester for the U.S. Forest Service’s Southern Region, Ed Hunter is helping expand the region’s wildfire-management successes to the rest of the country.

INTERVIEW BY ERIN VIVID RILEY

While growing up in the small city of Monroe, Louisiana, Ed Hunter would go hiking and camping as part of the Cub Scouts. A little over a decade later, he’d receive a call that would return him to the outdoors. Since joining the U.S. Forest Service in 1998, Hunter has steadily risen the ranks, and became a Deputy Regional Forester for the Southern Region last year.

Now Hunter oversees one of the country’s largest swaths of forested lands, consisting of 14 National Forests across just as many states and territories. He’s also at the forefront of the region’s wildfire-management efforts. We talked to Hunter about how the region continues to lead the country in controlled-burn attitudes, innovation, and collaboration.

How did you get your start with the U.S. Forest Service?

I went to Tuskegee University on a football scholarship. Unfortunately, I had some health challenges leading into fall semester and lost my scholarship. I was just about to go home when I received a call from the liaison between the Forest Service and the university. She talked about the forestry program and offered me a scholarship for a year. If I liked it, I could stay, and if not, I had a year of schooling paid for, so I gave it a shot.

What was your first experience with wildfire?

My first summer with the Forest Service, I went out to Spanish Fork, in Utah, and worked on a trails crew and just absolutely fell in love with natural-resource management. I got a chance to fight fire for the first time, and I was hooked.

What role has prescribed burning played in the South?

For us, prescribed fire has long been socially accepted in the South. It was adopted by early European settlers from the Native Americans, and has been used to manage forest conditions but also by farms to prepare lands to

PEOPLE OF PUBLIC LANDS

Hunter on Idaho’s Boise National Forest. Photo by the U.S. Forest Service

12 LIGHT & SEED

be planted. We also have very strong partnerships here. Eighty-seven percent of the forested land in the South is private, so we cannot be successful without working in an interagency and crossboundary way with our state, private, and tribal partners.

In addition to reducing wildfire risk, what other region-specific benefits are there?

A number of threatened and endangered species like the red-cockaded woodpecker, gopher tortoise, and the Louisiana pine snake are heavily dependent on open, grassy conditions that, in many cases, we can only produce with prescribed fire. The practice also supports regeneration of one of our keystone species, longleaf pine, which was almost decimated by overlogging in the early 20th century.

How has your wildfire strategy continued to grow and adapt?

To be the best partners to our communities, we’ve developed a tracking website that allows the public to see when and where our prescribed burns are playing. We’ve also continued to implement advances in technology that result in safer outcomes. This past year, we’ve increased

the use of drones. They accomplish roughly 10 percent of our prescribed burns, and we plan to do more in the future.

How is the Southern Region expanding its strategy nationally?

With the introduction of our Wildfire Crisis Strategy and Implementation Plan last year, we’ve been helping the agency develop training opportunities for Burn Bosses [private individuals who are certified to plan and execute prescribed fires]. And now our National Interagency Prescribed Fire Training Center, which opened in 1998 in Florida, is actually being replicated in the West. We’re very proud of that.

Learn more about Hunter and his region’s wildfiremanagement efforts at fs.usda.gov/main/r8/fire-aviation.

Hike the Appalachian Fire Trail, an interpretive route that spans Kentucky’s Daniel Boone National Forest and North Carolina’s Pisgah National Forest. Along the route, you’ll find informational signs that correspond to a podcast explaining the role and history of fire on the landscape.

13 PEOPLE OF PUBLIC LANDS

Hunter with a fire crew near the city of Weiser in Idaho. Photo by U.S. Forest Service

Ramsey with fellow hotshot Edward Klemencic on the Plumas National Forest

Photo by Kelly Ramsey

Ramsey with fellow hotshot Edward Klemencic on the Plumas National Forest

Photo by Kelly Ramsey

How my summers as a hotshot in Northern California changed my relationship to fire.

BY KELLY RAMSEY

Gale and I stood at the top of the rise, drip torches at our feet. Below us, the spine of Titus Ridge snaked downward, its Douglas fir-covered crest sloping down to the foaming rapids of the Klamath River. On the south side of the divide, the fire smoldered in the depths of a drainage. Scattered puffs of smoke rose quietly, looking deceptively peaceful, like the warm chimneys of a distant town. The fire was behaving, biding its time—but not for long. To the north, just a few forested miles away, lay a town of 1,000 people called Happy Camp. My home.

“This is bonkers,” Gale said. “Eight miles of line, and we’re left at the top with three torches.”

I grinned. He grinned. We both knew he wasn’t complaining.

“Ready?”

I picked up my torch. “Always.”

In late August of 2021, we’d been assigned to the McCash Fire, a 33,000-acre beast that first creeped, and then roared, from Ukonom Creek northward through the thick timber and sheer gorges of the Klamath National Forest. Our hotshot crew, based in nearby Six Rivers National Forest, had spent nearly four months on the road battling wildfires from the deserts of Arizona to the dense, primeval woods of Northern California. We faced at least two more months of nonstop emergency.

A busy fire season meant back-to-back 14-day assignments: removing trees and brush with chainsaws, digging miles of fire line, laboring in the dirt, and lighting

JOURNEYS 15 JOURNEYS

Ramsey on the Telegraph Fire in Arizona, 2021. Photo by Parker Kleive

backburn after backburn. We didn’t call it a backburn, though the word was technically correct—backburn, burnout, backfire, blacklining, all variations on fighting fire with fire. You’d ignite a section of the woods deliberately to deprive the approaching wildfire of fuel. Because we lit the forest so often, the canisters of diesel and gasoline comfortable in our gloved palms, we simply called the activity what it was: burning.

I often thought of fire as “good” only when it was preventative—pile burning, prescribed burning, and Indigenous cultural fire, all of which could reduce fuels, spur the growth of edible plants, provide forage for

wildlife, and reduce the chance of future wildfire. But a backburn—even one that didn’t smolder politely in the underbrush, as a planned Rx fire would, but instead romped, raged, and torched unpredictably—still tipped towards the beneficial side of the scale.

The Incident Management Team had for days monitored the McCash’s progress as it slunk toward Titus Ridge. They hemmed and hawed; would it gutter out in the drainage? Maybe rain would come and dampen the blaze to black drifts of wet ash.

But on the fourth day of our assignment, the McCash crouched in the chasm below the ridge, lined up for a run.

16 LIGHT & SEED

Ramsey with the whole crew, dubbed Smith River Hotshots, on the McCash Fire. Photo by Douglas Denlinger

“The proposition—cover ten times the ground you’d normally light, without support—sounded insane. But it was the only option, a desperate gamble to check the encroaching flank.”

This meant that if we didn’t do something, it would catch the bottom of the slope and go racing uphill. Flames tall as houses would slam the top of the rise and curl over the ridge in a screaming wave. If the ridge didn’t hold, the fire would head straight for Happy Camp.

Not only did I personally dread a wildfire coming for my house, dogs, and annoying goat, Sam, but half the town had been leveled the year before by the Slater Fire, one of many blazes fueled by 60-mile-per-hour winds that had incinerated communities all along the West Coast in the so-called Labor Day Firestorm. The grieving residents of Happy Camp couldn’t handle a repeat performance.

So the management team turned to us. We were semilocal, known as “a burning crew.” They asked for a Hail Mary pass: light the seven or eight miles of line between the Johnsons Hunting Ground trailhead and the Klamath River before the wildfire hit the ridge.

Under normal circumstances, a hotshot crew can feasibly burn no more than a mile in a single shift. Multiple crews

collaborate on lighting, and an array of engines, water tenders, and support staff spread out along the line, ready should embers cross the road. Helicopters are also on standby, ready to let loose buckets of rain.

This time, we’d have no help. Just the 20 of us and a long, spiny wrinkle on the surface of a burning planet. The proposition—cover ten times the ground you’d normally light, without support—sounded insane. But it was the only option, a desperate gamble to check the encroaching flank.

We said yes. We had to try.

“Save Kelly’s goat!” the guys joked as we filled our torches. I laughed, thinking, Seriously. Please let us save this dumb animal.

We dripped blue flame from the tips of our torches along an old forest road. We lobbed incendiary canisters down the slope into thickets of ceanothus and manzanita, watching them explode in sparks. Flares launched from pistols—the pop of a gunshot, a breathless pause as the

The burn on Titus Ridge outside Happy Camp, California. Photo by Forrest Gale

17 JOURNEYS

The Smith River in Six Rivers National Forest

Photo by Geoff Liesik, courtesy of the Bureau of Land Management

The Smith River in Six Rivers National Forest

Photo by Geoff Liesik, courtesy of the Bureau of Land Management

flash sailed in a high arc over the trees, and the sizzling pfffffft of contact. Gradually, flames licked the ridge and carpeted its western flank in glittering orange. Smoke formed a castle above us, a second billowing mountain range in the sky.

Most of the guys took this in with a disaffected gaze. They had long ago accepted destruction as part of the job. For me, though, this vision of death always stung. I’d chosen the Forest Service because I was a backpacker and an environmentalist. I was here out of a love for trees. Seeing them torched to black matchsticks made me want to weep.

I reminded myself that we sacrificed these acres to save the thousands, maybe millions, of acres at our backs. This wall of Roman candles was, in a sense, good fire.

Incredibly, we pulled it off. We burned from early morning

“I reminded myself that we sacrificed these acres to save the thousands, maybe millions, of acres at our backs. This wall of Roman candles was, in a sense, good fire.”

until well after dark, when we stood on the far bank of the river watching shimmering flames cover the ridge like bright cities on a blackened plain.

After a few hours of sleep, we returned to check our work. The blaze had slopped over the road in a saddle, so we spent the day digging hand line around a 20-acre spill of downhill-flowing fire. When we’d contained that piece, we saw that otherwise, our barrier had held.

It felt miraculous. In a line of work where we suffered more losses than wins, and where I wrestled with the smallness of our victories relative to the mass destruction of wildfires, the legendary burn on the McCash was a bright spot in the dark. The fire would grow to the east and south, reaching nearly 100,000 acres by its late October end, but our northern perimeter never faltered. Happy Camp was safe.

Keep an eye out for Ramsey’s first book, a memoir about fighting wildfires in the West, forthcoming from Scribner in 2025.

A writer whose work has appeared in The Washington Post, Sierra, and American Short Fiction, Kelly Ramsey has worked as a wilderness ranger and wildland firefighter for the U.S. Forest Service. Follow Ramsey on Instagram at @kellylynnramsey and read her newsletter at plantperson.substack.com.

Ramsey sitting near the North Fork of the Smith River. Photo by Meredith Kohut

19 JOURNEYS

FINDING THE FUEL

A newly applied mapping technology could help manage the proliferation of highly flammable Eastern red cedar across the Great Plains.

BY MORGAN O’HANLON

THE RESPONSE

Eastern red cedar trees grow near a river bank in Central Nebraska

Photo courtesy of USFS Bessey Ranger District

At the edge of the Sandhills, the world’s largest intact grassland, sits the Nebraska National Forest. On a clear and windy fall morning in October 2022, flames raged through its dense thicket after an overturned all-terrain vehicle ignited brush. That kindling grew into a blaze that quickly swallowed a youth camp, jumped a highway, and burned through 14,000 acres of private rangeland.

Since then, Greg Wright has used the Bovee Fire, as it was called, as a warning against the region’s out-of-control red cedar population. As a wildlife biologist at the nearby Bessey Ranger District, it’s his job to make sure the grasslands stay intact. And right now, he says, a manmade cancer threatens its existence.

The U.S. Forest Service planted the Nebraska National Forest amid fears of a national timber shortage in the early 1900s. Of the species introduced, Eastern red cedars thrived. Today, they make up more than 50 percent of the forest’s woody growth and have spread far beyond its bounds. Forty-four million acres of the Great Plains have converted to tree cover due to this encroachment. That’s an area roughly the size of Oklahoma.

Their proliferation has coincided with an increase in the magnitude and frequency of extreme fires throughout the region. A type of juniper, Eastern red cedars burn hotter and easier than most other coniferous trees due to oil-rich leaves and low-lying foliage. Once ignited, their dense thickets make fires even more difficult to contain. Not only are they more fire-prone themselves; they are also quick to inhabit areas disturbed by wildfire.

According to projections by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the region encompassing the Sandhills, as well as South Dakota’s Black Hills National Forest and Badlands National Park, is expected to see more growth in large fire weeks than anywhere else in the country.

Trying to get ahead of the danger, regional fire managers like Wright have prioritized thinning existing clusters and stamping out signs of early encroachment on grasslands. And thanks to a newly applied mapping technology, managers may soon be able to accurately chart the terrain, assess where efforts should be concentrated,

and most importantly, help landowners fully understand the threat.

For close to a decade, a group of researchers at Colorado State University has been using LIDAR to map the spread of red cedars in Nebraska. LIDAR, which stands for light detection and ranging, works similarly to sonar or radar, only with visible light waves. Aircraft beam lasers onto the land below and collect the data that returns; the university team then uses that data to essentially create 3-D maps of the ground, which are used to tell where trees are concentrated.

“By acting faster, we’re able to act cheaper. It’s analogous to detecting a disease as early as possible to have the best chance of survival.”

—Greg Wright

“With something like LIDAR, we can actually map red cedar cover across the entire region from zero to 100 percent and detect some of those earlier stages of encroachment,” said Steven Filippelli, one of the research associates studying innovations in mapping. By graphing the data according to density and strength of LIDAR points, researchers can identify the quantity and size of trees, even saplings. “By acting faster, we’re able to act cheaper,” said Wright. “It’s analogous to detecting a disease as early as possible to have the best chance of survival.”

21 THE RESPONSE

The ability to pinpoint early growth would also benefit the dozen or so prescribed-burn associations operating in Nebraska. “It doesn’t take anything to kill a three- or four-inch tree,” said Tell Deatrich, a rancher and member of the Loess Canyons Rangeland Alliance. The 80-member association has collaborated on reclaiming more than 90,000 acres of grassland to date. But these volunteerbased organizations, made up of farmers and ranchers, are often strapped for resources.

So far, Filippelli and his team have created maps for Custer County, but their accuracy and readability are works in progress. For instance, the health of the grasslands depends in part on native deciduous trees, and LIDAR mapping can’t always distinguish between these and red cedars, Filippelli said. As a result, his team is testing other algorithms, a process that could take years. The fast speed at which red cedar grows can also cause

challenges. “Due to the high cost of LIDAR, it’s unlikely that [new data] will be collected frequently enough for detecting red cedar expansion in real time,” said Filippelli.

Despite these limitations, Filippelli believes the large-scale applicability of mapping fire-prone species is crucial to the future of wildfire management, and not only for Nebraska. “We hope the method we develop could be used to map evergreen tree cover anywhere in the U.S.,” he said.

More than 97 percent of Nebraska is privately owned, meaning there are thousands of landowners who may or may not even be aware of the threat growing on their property. It also means that fire managers in the region need widespread buy-in from these landowners.

A powerful tool at their disposal has been the Rangeland Analysis Platform (RAP), a public geospatial mapping tool released by the USDA in 2018 to help guide land-use

Point

7000 1500

Intensity Eastern Redcedar Deciduous

22 LIGHT & SEED

A map of Eastern red cedars developed using LIDAR technology. Photo courtesy of Steven Filippelli

decisions. Using satellite-based data gathered since 1986, the platform allows the public to see how red cedars have rapidly converted open fields to woodland in just a few decades.

But RAP’s moderate-resolution satellite imagery and significant margin of error makes it ineffectual when it comes to real-time mitigation. “If the map shows zero percent tree cover, there could in fact be trees present. Or, if it shows 10 percent cover, there could in fact be no trees,” said Filippelli.

While the visual aid has helped managers and prescribedburn associations educate landowners about the threat of encroachment, convincing them to mitigate using controlled burning is another issue. Ranchers in the Sandhills, a region north of their jurisdiction, have been more reluctant to adopt these methods out of fear that the blazes will impact their rangeland, leaving it barren of grass. “If you went right in and told them, ‘Hey, you guys got to start burning,’ that’s not a good way to get your point across,” said Wright. “It’s a good way to end a conversation.”

Armed with the specificity that LIDAR maps can provide, managers hope to show how targeted and moderate these burns can be. “This technology will be helpful for landowners to see that we can kill these with really safe fire, and that it will be extremely effective,” said Deatrich. “The default is to do nothing, but we can’t do that in this case. We have to actively manage.”

Spend a weekend exploring the Bessey Recreation Complex of Nebraska National Forest to see firsthand the progression of red cedar encroachment in the Sandhills from east to west.

Morgan O’Hanlon is a freelance reporter based in Austin, Texas. When she’s not in a canoe or on her bike, she writes about endurance sports, the outdoors, and politics.

23 THE RESPONSE

Crews patrol mow lines during prescribed-fire operations on the Bessey Ranger District of Nebraska National Forest. Photo courtesy of USFS Bessey Ranger District

The Upper Arkansas Valley in San Isabel National Forest

Photo by Kellon Spencer

The Upper Arkansas Valley in San Isabel National Forest

Photo by Kellon Spencer

A FIRE KNOWS NO BOUNDS

In central Colorado, an innovative funding model is treating forests across borders to keep high-risk communities safe.

BY LISA JHUNG

On the eastern flank of 14,200-foot Mt. Princeton in the San Isabel National Forest sits 120 acres split among four landowners. Like many of the private plots in Chaffee and Lake Counties, it abuts state and federal land. And like much of the region, which suffered a 9,000-acre burn in the 2019 Decker Fire, the health of the landscape has been gravely impacted by over a century of wildfire suppression and the increasing impacts of climate change.

NFF FIELD REPORT 25 NFF FIELD REPORT

As a result, species like Douglas-fir beetle, spruce beetle, budworm, and mistletoe have proliferated to a greater extent than they would have under pre-colonial forest conditions, throwing off the land’s natural composition.

Paul Larger, who co-owns one of the four plots, watched as Mt. Princeton changed from green to brown over the past few years. “It’s a big concern for everyone,” he said about the damage the propagation has caused. When he and a friend bought the property in 2019, “it had so much tree fall that you could barely hike through the property, much less drive a tractor or ATV on it.”

That was the case until Larger received an enticing proposition: a comprehensive ecological restoration of the wildfire-prone landscape, with the help of the Colorado State Forest Service and the Colorado Strategic Wildfire Action Program, as implemented by the National Forest Foundation’s Upper Arkansas Forest Fund (UAFF).

Created in 2020 to decrease the risk of severe fire to communities in central Colorado, the UAFF is a unique model for conservation finance. It’s set up like a bank account, for which funding comes in from various entities via grants that are then allocated to perform forest restoration and fuel reduction across both public and private lands. Funds are managed by the NFF’s Central Colorado Project Coordinator, Matt Nykiel, who facilitates everything from community outreach to contracting timber companies to undertake thinning.

“Most timber in Colorado forests is not worth much, and paying loggers to come cut and remove trees can be several thousand dollars an acre in some cases,” said Dave McNitt, a wildlife biologist with the BLM, an important partner of the UAFF.

“There are a lot of different funding sources out there, but it can be difficult, or in many cases, impossible, to line them up for a project.” That’s where the UAFF comes in, handling what McNitt calls the “real work,” so that foresters and biologists like himself can focus on on-theground efforts.

“We know fires do not know any jurisdiction— they’ll burn through whatever they want to.”

—J.T. Shaver

The funding model allows for innovative partnerships, from the Colorado Department of Natural Resources to unique community-based initiatives, such as the passing of a countywide ballot tax initiative driven by the group Envision Chaffee County.

26 LIGHT & SEED

Tractors performing forest-thinning operations. Photo by Kellon Spencer

Crew members evaluating a parcel of San Isabel National Forest

Photo by Emily Lord

Crew members evaluating a parcel of San Isabel National Forest

Photo by Emily Lord

The single largest contribution has been $5 million from the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), an agency of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Along with the varied benefits of the UAFF, such as natural-resources conservation and wildlifehabitat improvement, what drew the NRCS’s Regional Conservation Partnership Program to the UAFF was its ability to “leverage resources to treat a communityidentified forestry project,” said Clint Evans, state conservationist for the NRCS. After all, the program specifically helps private landowners and managers.

This investment in cross-boundary work has meant focusing on community buy-in. The Colorado State Forest Service (CSFS) and other partners convened by the Chaffee and Lake Forest Health Councils work together to get landowners on board by going door-to-door and cold calling folks who own high-priority parcels that have been identified by community wildfire protection plans developed by Chaffee and Lake Counties.

“We know fires do not know any jurisdiction, they’ll burn through whatever they want to,” said J.T. Shaver, the supervisory forester of the CSFS. “Our hope, always, is to do as much cross-boundary work as possible.” The key to achieving this is to get a group of neighbors to agree to a project that is big enough to be cost-efficient. That is where individuals like Paul Larger play a major role.

“I was like, did we just win the lottery?”

—Paul Larger

In late 2022, when Larger got the call from Shaver, he immediately saw the potential of the UAFF’s proposal.

“I was like, did we just win the lottery?” said Larger. The previous year, he and a few friends had taken down 300

28 LIGHT & SEED

A crew member marking the boundaries of a thinning project. Photo by Emily Lord

dead trees using chainsaws. After he signed on to be a part of the project, Larger helped coordinate with his three neighbors. Soon after, the fuel-reduction work began.

Following work the UAFF began in the fall, Larger’s 40 acres are in much better shape: dangerous fuel sources have been removed and new grasses, Ponderosa pine trees, and aspen stands have emerged, attracting deer and elk. It is a regenerative effect that once fully implemented is expected to impact up to 50,000 acres on and around the San Isabel National Forest by 2033.

Shaver credits Larger for being a spark plug. “We can preach it all we want, but sometimes it truly does take neighbors talking to get the buy-in,” he said. Larger, meanwhile, has embraced his new role as facilitator. “This whole program has forced me to learn so much about forestry,” he said. “Instead of spending nine more years cutting diseased and dying trees, our plan will now be to get the right depth of mulch and plant new trees.”

The future of wildfire mitigation in the area and beyond will require collaborating across interests, authorities, and boundaries—and embracing an approach that’s constantly

shifting in the face of climate change. And that, said Nykiel, “means private property owners taking a more active and responsible role in stewarding the ecosystem in concert with their public-land neighbors.”

Hike on a 5.7-mile out-and-back trail to a waterfall via the Wagon Loop and Browns Creek Trail in San Isabel National Forest for views of 14,276-foot Mt. Antero.

Lisa Jhung is a Boulder, Colorado-based writer and editor who’s contributed to national publications, outdoor industry brands, and nonprofit organizations. She is also the author of two illustrated, humorous running books, “Running That Doesn’t Suck” and “Trailhead: The Dirt on All Things Trail Running.”

Consulting the crossboundary map. Photo by Emily Lord

29 NFF FIELD REPORT

HEARD IN THE WOODS

“It’s not if we get fire, it’s when we get fire.”

Travis Woolley, Forest Ecologist, The Nature Conservancy, as quoted in azcentral

“It was said that then two people would be chosen to go burn beneath the huckleberry bushes. Then that area would be burned but not with a real hot fire. It was said that that area would be left alone for about two years at which time the bushes would then have regrown to a certain height. It is said that then the huckleberries would be plentiful. “

Felicite “Jim” Sapiel Pierre McDonald, Salish elder and an advisor with the Salish-Pend d’Oreille Culture Committee, as quoted on CSKT

“We tend to think of fire as this malicious thing that we can’t work with because it’s inherently unpredictable. But, in fact, fire does things in a very predictable way. And once you understand how fire behaves, you can change how you’re putting fire on the ground.”

Chris Adlam, Regional Fire Specialist, Oregon State University Extension Service, as quoted in Mongabay

“Every fire really matters. Native forests are so critical for our culture, for our water supplies, and for preventing flooding and erosion.”

Emma Yuen, Statewide Program Manager, Native Ecosystems Protection & Management, Hawaii Division of Forestry and Wildlife, as quoted in a state-issued press release

Shoshone National Forest, Wyoming

Photo by the U.S. Forest Service

“[Fire] was pretty much completely squashed for two generations, and so we lost that cultural continuity, and I think that is one of the struggles in the West right now, is to build back that culture of fire.”

Lenya Quinn-Davidson, Fire Network Director, University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources, as quoted in Mongabay

“Deliberately restoring fire in order to avoid the negative outcomes of fuel buildup and climate change can increase the natural qualities of these places while honoring human relationships with the land that predated their designation as wilderness.”

Jonathan Coop, Director of MS in Ecology and Professor of Environment and Sustainability, Western Colorado University, as quoted in Gunnison Country Times

“As climate change drives longer, more intense, and more dangerous wildfires, every community across the country is experiencing the impacts—whether from smoke-filled skies or catastrophic losses.”

Deb Haaland, Secretary of the Interior, as quoted in a state-issued press release

“Even though there was frequent lightning fire, and that was an important element understood culturally, a lot of meadows and forest openings were maintained through Indigenous peoples’ intentional and purposeful use of fire—in the right way, at the right time, and under the right conditions.”

Frank Kanawha Lake, Research Ecologist and Wildland Firefighter, U.S. Forest Service, as quoted on Biohabitats.com

“We’re starting to see the fingerprint of wildfire smoke on overall air quality trends over the entire country, not just in the western states where these fires are burning most often.”

Marissa Childs, Former Fellow, Harvard University Center for the Environment, as quoted in Stanford News

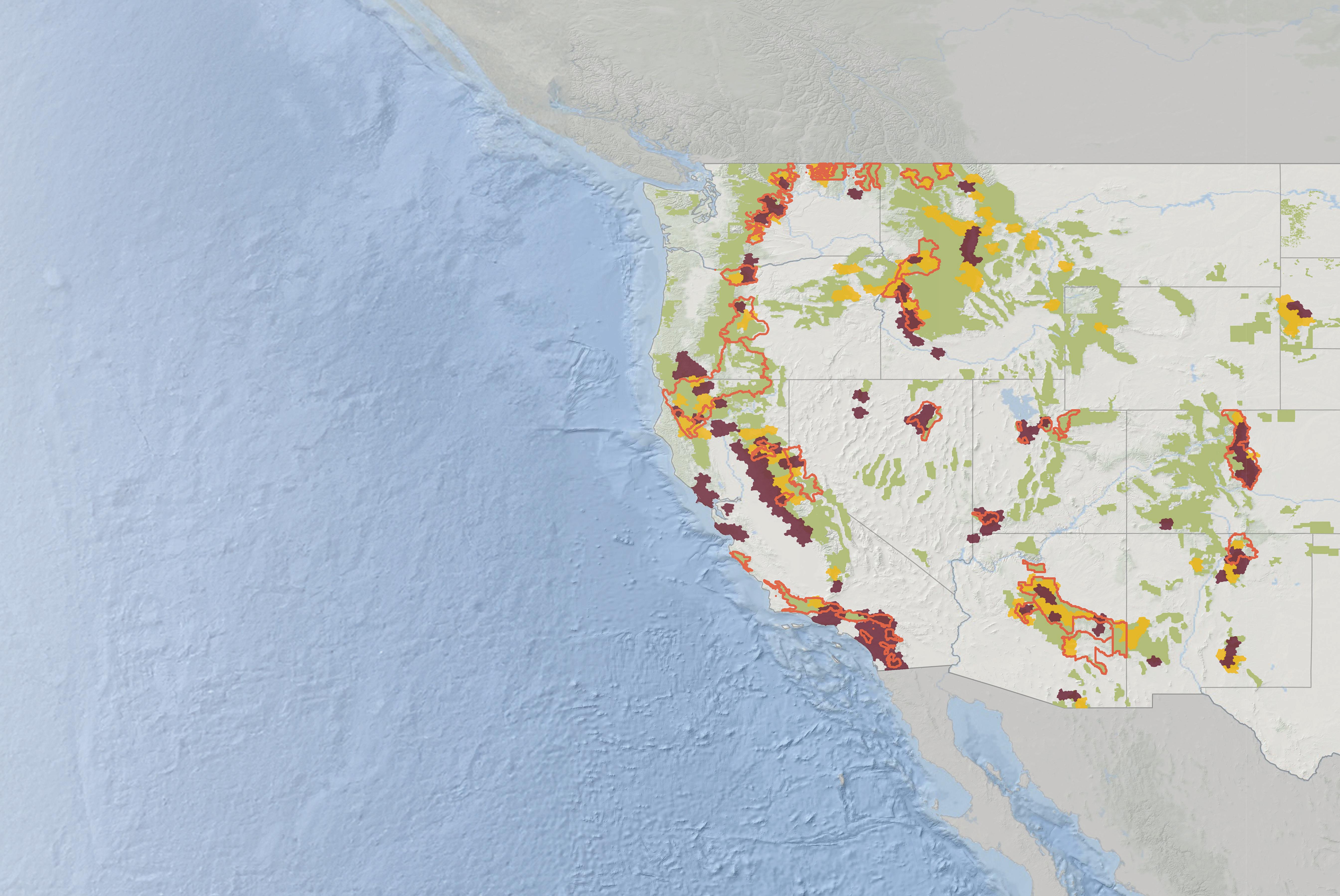

MEETING THE MOMENT

The Wildfire Crisis Strategy emphasizes a cross-boundary approach to reducing risk at the landscape level.

BY CAROLYN BUCKNALL

In 2023, smoke from Canadian wildfires introduced millions of people on the East Coast to the eerie, orange haze and poor air quality that have become an all too familiar reality in the West. Over the past two decades, wildfires have grown larger, burned longer, and caused more destruction, pushing many western states—and the country—to the brink.

Recognizing the need for a new approach, the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) released the “Wildfire Crisis Strategy and Implementation Plan” in January 2022. With it, the USFS will prioritize fuels-reduction work across public-private property boundaries on 21 landscapes that have the highest risk of community exposure to wildfire.

To protect these communities, the agency will work with a wide range of tribes, local governments, private landowners, and conservation organizations to treat all lands, regardless of designation. As one of the USFS’s leading implementation partners, the National Forest Foundation conducted ten roundtables among these groups in 2022 to strengthen opportunities for

collaboration and identify actions for group members to take.

Over the next decade, the NFF will work alongside the USFS to reduce wildfire risk across 11 landscapes, restoring these forests and their natural fire regimes.

The strategy’s focus on cross-boundary partnerships and landscape-level treatments offers a promising answer to the urgency and scale of the current moment. Just as important, it lays the groundwork for sustained investment in work that will keep communities safe and forests healthy for future generations.

Open the foldout to learn more.

THE LAST WORD

32 LIGHT & SEED

Photo by the U.S. Forest Service

“

After many years of fire exclusion, an ecosystem that needs periodic fire becomes unhealthy. Trees are stressed by overcrowding, fire-dependent species disappear and flammable fuels build up and become hazardous.”

—U.S. Forest Service Wildfire Crisis Strategy

The NFF in Action

A look at three wildfire crisis landscapes

Southern California

Los Padres, Angeles, San Bernardino, and Cleveland National Forests; 4 million acres

In Southern California, 25 million people live in the Nation’s largest concentration of high-risk firesheds. Through collaborative vegetation management and ignition reduction, the NFF is working to reduce wildfire exposure across these forests.

Colorado Front Range

Arapaho-Roosevelt and Pike National Forests; 3.5

acres

This region has seen four of the five largest fires in Colorado history since 2018; the largest two, impacting nearly five million residents, both took place in 2020. In response, the NFF and its partners are increasing the pace and scale of forest restoration across the Front Range.

Circle Carson National Forest; 1.5 million acres

This area of Northern New Mexico has high-risk firesheds that encompass many culturally diverse groups with deep traditional ties to the forests and grasslands of the area. The NFF is utilizing local knowledge to prioritize the values of these communities as it plans wildfire risk-reduction treatments.

The Wildfire Crisis Strategy and Implementation Plan:

All Lands Crisis Strategy Firesheds Wildfire Crisis Strategy Landscapes USFS Lands Crisis Strategy Firesheds National Forest Lands

Southern California

Enchanted Circle

Colorado Front Range

Enchanted

million

landscapes across 134 firesheds acres on National Forest System lands acres of other federal, state, tribal, and private lands years to implement Acres

Since 1983 1983 1986 1989 1992 1995 1998 2001 2004 2007 2010 2013 2016 2019 2022 10M 8M 6M 4M 2M 0

21 20M 30M 10+

Burned By Wildfire

Create 300,000 to 575,000 jobs Protect homes and communities Improve air and water quality Firesheds

about 250,000 acres in which an ignition can spread and expose communities to wildfire Basemap created with data from Airbus, USGS, NGA, NASA, NOAA, CGIAR, GEBCO, NCEAS, NL and the GIS User Community, Esri, GEBCO, Garmin, NaturalVue

Photos by Brian Cavallaro, Tayler Jones, and Jon Cook

Data

from the National Interagency Fire Center

are landscapes of

National Forest Foundation Building 27, Suite 3 Fort Missoula Road Missoula, Montana 59804

406.542.2805

© 2024 National Forest Foundation. No unauthorized reproduction of this material is allowed.

Light & Seed ™

Editor-in-Chief: Hannah Featherman

Editor: Erin Vivid Riley

Writers: Kelly Ramsey, Morgan O’Hanlon, Lisa Jhung, Carolyn Bucknall

Designer: Shanthony Art & Design

Why We Print

At the National Forest Foundation, we believe forests and grasslands are as vital to all communities as clean air and water. Through Light & Seed, we aim to share stories that connect you to the incredible lands of the U.S. National Forest system.

Sustainable Printing

Light & Seed is printed on recycled paper made of 30% post-consumer content. This FSC-certified paper ensures the highest environmental and social standards have been followed throughout the processes of wood sourcing, paper manufacturing, and print production. More at fsc.org.

Photos by Kelly Ramsey, the U.S. Forest Service, and Emily Lord

Photos by Kelly Ramsey, the U.S. Forest Service, and Emily Lord

JULY 8-14 IMMERSE YOURSELF IN THE AWE OF NATIONAL FOREST WEEK FIND OUT MORE AT WWW.NATIONALFORESTWEEK.ORG

Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest

Photo by Quinn Bosselman

Photo by Kelly Ramsey

Photo by Kelly Ramsey

Photo by Kellon Spencer

Photo by Kellon Spencer

Ramsey with fellow hotshot Edward Klemencic on the Plumas National Forest

Photo by Kelly Ramsey

Ramsey with fellow hotshot Edward Klemencic on the Plumas National Forest

Photo by Kelly Ramsey

The Smith River in Six Rivers National Forest

Photo by Geoff Liesik, courtesy of the Bureau of Land Management

The Smith River in Six Rivers National Forest

Photo by Geoff Liesik, courtesy of the Bureau of Land Management

The Upper Arkansas Valley in San Isabel National Forest

Photo by Kellon Spencer

The Upper Arkansas Valley in San Isabel National Forest

Photo by Kellon Spencer

Crew members evaluating a parcel of San Isabel National Forest

Photo by Emily Lord

Crew members evaluating a parcel of San Isabel National Forest

Photo by Emily Lord