3 minute read

Ripping Bill Scheller

Ripping

Advertisement

I woke up in Winnipeg, around dawn.

It had been a bad night for sleeping on the train. Four young snots had gotten on in Moose Jaw, and they didn’t like the seats they’d been assigned in the forward coach. So they wandered back to my coach, which was reserved for long-distance passengers. A porter had told them to move back to where they belonged, but they ignored him, sprawled out, and went to sleep. The porter got the conductor, who showed up and shook them awake. He was gruff and dead serious, and off they went to their assigned seats. The good conductors are all part cop.

That little fracas, and three girls who sat gabbling across the aisle, had kept me up. Now it was five o’clock, but even though the louts were gone and the girls had nodded off, I wasn’t going to get back to sleep. Yvette the old railroad lady took care of that.

She had a bull’s body and a bullhorn voice. She’d gotten on in Brandon, Manitoba, where there was no night ticket agent, and parked herself in the row behind me. She slept for a couple of hours, and got off during our layover in Winnipeg to get her ticket to Chapleau, Ontario. When she got back on, she was ready to start talking, fastening on a couple across the aisle. Steam engine of a woman

Yvette was pushing seventy. She was the widow of a railroad man, a lifer on the Canadian Pacific. This entitled her to travel on his lifetime pass, which she had shown the teenage girl at the ticket window in Winnipeg. The girl, who likely had never before seen such a thing, gave her a hard time. What came next was something else she’d probably never seen – the explosion of a living, breathing steam engine of a woman. We heard all about it as we pulled out of Winnipeg, but it was only the opening volley of a take-no-prisoners tirade.

“She was chewing gum, for Chrissake and she comes out with a smart remark,” Yvette boomed. “She didn’t know what the hell the pass was, and she says it’s no good. Did I rip into her! I told her my husband was a dispatcher – asked her if she knew what that was, and she didn’t! I told her she wouldn’t have a job if it wasn’t for men like him, that the trains wouldn’t even run!”

When she was done with the girl, she ripped into the city of Winnipeg, the province of Manitoba, and everybody who worked for the railroad “west of T’under Bay.” “Ripping” was her catchall word for a hoarse verbal battle with the world. Verbal? We even got to hear about the time she gave her abusive bum of a son-in-law a black eye. “I used to weigh 238,” she said, “but now I’m down to 186.” Fighting trim.

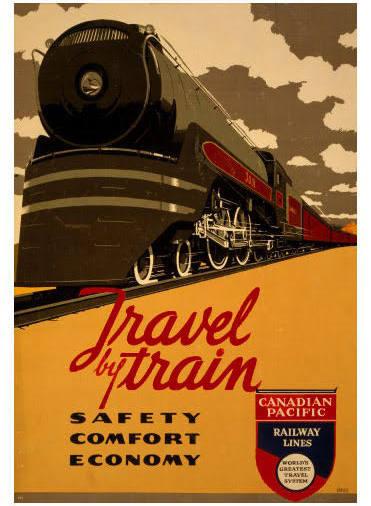

The railroad itself – the mighty Canadian Pacific Railway, the CPR – was the godhead of days gone by, its people and machines heroes of the way things were and the way they still should be. Yvette’s husband – “he was a good man, and he worked like a bastard” – had put in forty-six and a half years on the CPR, and her father had been an engineer. One or the other of them had even gotten her in on the act. “I switched steam engines in a roundhouse,” she boasted. “They even have pictures of me doing it in one of the maintenance shops.”

“You’re lucky one of them steam engines didn’t run away on you,” one of her listeners said.

“The steam engines are lucky they never tried,” she snorted back.

I didn’t doubt that Yvette was a match for the iron horse, and for anything or anyone else that had stood in her path as she rattled down the rails of life – the ticket girl in Winnipeg was but a pebble on the track. But it was plain to see what really had her ripping. Her dispatcher husband had died right at retirement. She must have had a notion of the two of them traveling around Canada on passes for years, and now it was just her, and a pass she had to fight to have honored. Yvette was stuck on a siding, stranded in a gum-snappers’ world.