11 minute read

Postcard from a Colorado Stream John H. Ostdick

In Quiet Nights In quiet nights I reminisce A child’s laugh, a lover’s kiss A careless word’s enduring pain A girl I met once on a train Pleasant times with friends now passed Questions which had not been asked Holding hands in first love’s thrill Some regrets that linger still Success the prize from effort driven A stranger’s kindness, freely given A falling star, the Milky Way TV dinners on a tray Summer’s breeze, a warm caress A shattered glass, clean up the mess Boating on a moonlit lake Saying goodbye at a wake Freshly baked, the smell of bread There’s my daughter being wed “I love you” unsaid all too often As the hearse leaves with her coffin Yawning, heavy eyelids close A prayer to find peace in repose.

Postcard from a Colorado Stream

Advertisement

At some point in your life, you finally realize it’s not about catching fish.

Story and Photos by John H. Ostdick

Crested Butte, Colorado— Not everyone grows up with a fly rod in hand.

If you do, your life is likely filled with amazing moments stacked upon amazing moments. For the rest of us, we’re lucky to wade in when we can and spend the rest of our days playing catch-up.

My friend, Bart, is at home in these mountains. He started fly fishing in Colorado as a young boy. To him, the state means rivers, mountains, and a long driving escape from Texas flatland, where our daughters grew up together.

Watching Bart work a river is mesmerizing. He spends as much time in the rivers here as he can. Blessed with an MIT brain, incredible vision, and quick reflexes, he is the epitome of the fly fisherman. During times that we have fished together, after I’ve retired for the day, I like to retreat

“ . . . feeling the tug of the current and savoring fluid movements of fly rod and line . . .”

to a vantage point, grab a beverage, and watch him play.

Last August, what started as a simple invitation from Bart and his wife, Elizabeth, to my wife, Michelle, and me to visit the home they’ve built slowly morphed into a reunion of sorts for their daughter, Meg, my New York daughter, Madeline, my son, Hunter, and Bolton, another close childhood friend of theirs, plus significant others.

In the ensuing days, Bart generously shared his fishing life’s education with Hunter, my daughter’s partner, Vince, and Bolton’s husband, Blaz. Years have passed since Hunter was fly fishing, and neither Vince nor Blaz had been before. From pond practice to river experience, Bart patiently coached them to land trout before the weekend was over. At her request, Bart demonstrated to Meg’s partner and capable angler, Liz, how to properly filet a fish. Blaz admitted that he had no idea what to expect. His only reference point is fly fishing in movies, and “although it looked fairly simple, I expect there to be a serious learning curve.”

The generational transfer of love of place and experience is critical. To really care about something like the need for natural places, especially for urban dwellers, firsthand knowledge is critical. My main fishing experience growing up was catching bream with a cane pole or bass or crappie after flinging line from an inexpensive rod and Zebco reel into Texas lakes.

The Gunnison-Crested Butte area, however, holds a special place in my heart. It is a prime playground, offering about two million acres of pristine wilderness. The region is strewn with old ghost towns, as well as charming little spots with quaint names such as Tincup and Marble. The local rivers, however, are my touchstone. Hatcheries in Gunnison County, the equivalent size of Connecticut, release more than three million new fish each year.

For eight consecutive years during my forties, I joined a special group of men (including Bart a couple of those years) each Labor Day for long-weekend escapes into these fish-rich rivers. I was a shaky fly fisherman at the beginning, and merely adequate when our annual host sold his place on the East River in Almont, Colorado and the band split up.

While it’s easy to wax poetic about standing in the middle of a thirty-foot-wide river, towering cottonwoods on both sides, feeling the tug of the current and savoring fluid movements of fly rod and line, capturing the sense of peace it gifts me is

more difficult. I’ve missed the joy I experienced floating or in wading the area rivers ever since.

A Son’s Introduction

During intervening years, I intended to introduce Hunter to this special Colorado experience, but our diverging lives just never quite aligned for the opportunity. I’m afraid Hunter’s first flyfishing adventure established a benchmark that he may never replicate. When he was 12, our family (his mom, 10year-old sister, and I) flew in a floatplane 250 miles north of Vancouver, British Columbia, touching down in front of Hakai Beach Resort on Calvert Island (now the Hakai Institute, a foundation-run science research operation). Our stay’s highpoint was a helicopter dropping us into the shallows of the Koeye, one of Canada’s most majestic rivers, in steady rainfall. A legion of pink salmon and steelhead trout swarmed the frothy, chilled waters as our two guides helped us present flies into the middle of them. With the guides’ assistance, both Hunter and Madeline started hooking trout before I even got a cast out. Hunter, in the bit-gangly and adolescently awkward stage on land, showed a stunning grace with fly rod in hand. All of us netted a dizzying catch of rainbow trout and salmon before the helicopter picked us up for a return to the resort.

Almost four years later, Hunter and I had another amazing helicopter fishing sojourn at the Nimmo Bay Resort, deep in the tangled rainforest wilderness of mainland British Columbia, near the Broughton Archipelago off the northeastern tip of Vancouver Island. Although swollen streams hindered many of our efforts, we were dazzled flying over and dropping down through spectacular scenery to land on islands or rock beaches. We caught a few dolly vardens and steelhead trout on some spin-cast rigs but were mostly frustrated in our fly-rod forays. Unfortunately, those two spectacular flyfishing experiences were the last Hunter and I managed together, for one reason or another, until this trip with him, this time as a young man.

On our first full day in Crested Butte, Hunter, Bart and I did a float trip on the Gunnison River, a classic Rockies trout stream. The river, which has the nation’s biggest Kokanee salmon run and the largest trout concentration in Colorado, starts in Almont at the confluence of the East and Taylor rivers and flows 25 miles downstream.

The river’s North Bridge Run between here and Whitewater Park is generally gentle, with several very good fishing pools along the way. It starts out at North Bridge on Highway 135, floats for a couple miles through some subdivisions before turning and going beneath some large cliffs called the Palisades, and then heads down a couple more miles to the Whitewater Park. The pace is pleasant, and the fish are usually active.

As we hit the river the water temperature was in the process of changing, and the fish were hanging out deeper, making us work harder. Hunter had a big smile on his face as he and Bart bantered back and forth. He

Hunter and Dad, Photo by Thomas Santalab, Delta Sky magazine

caught a couple of small trout, but the only thing I netted from the rear of the boat was a little humility.

In for a Dip

As we approached our takeout point, I was leaning out of the boat, working a ledge where I’ve had success in the past. As I extended out with my cast, Bart ran over a boulder that protruded slightly above the water line. When the back of the boat rose abruptly, so did I, plopping into the middle of the shallow, fast-moving stream. Flash of cold, voices from a yard off the river first gasping, and then yelling out, “Are you all right?”

In a sitting position in the middle of the stream with water just below my shoulders, I responded, “The water is great. Come on in.” Laughter. Bart was now anchored about 40 yards ahead of me. Between the speed of the river and the shallowness of my position, I couldn’t really stand, so I just bounced along on the rocky river bottom on mine until I reached the boat, where Bart helped me aboard. By this time, Hunter had already dug his phone out of the dry bag and texted his sister about the turn of events, so I just owned the humor of the moment.

Later in the day, Bart gathered Hunter, Vince, and Blaz to a pond outside his house for a little cast instruction. They are all in their early 30s, have bright minds, and took to his instruction easily.

“Having only fished with a bobber before, on the first evening, my overwhelming concern was about getting a hook stuck in myself somehow, whipping an eyelid or an earlobe off with those great big fly casts,” Vince recalled later. “It came as some surprise that there's little danger to yourself when fishing with a fly, but Bart conspicuously positioned the three novices a good 10 yards apart. That told me something about the real cause for concern. I still managed to snag a few low-lying plants and jabbed my thumb with the hook while stowing it more times than I'd care to say.”

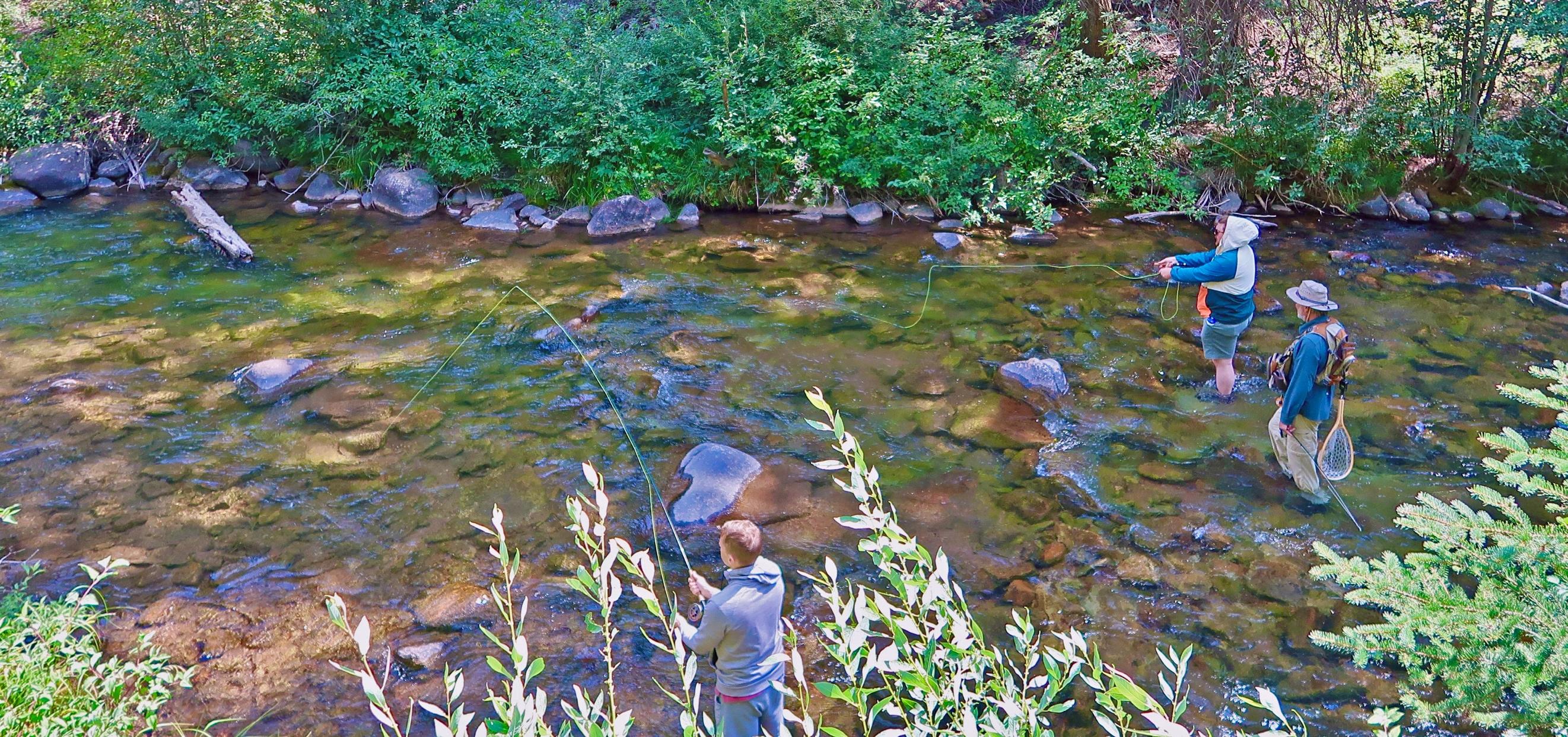

One day, Bart took us to Spring Creek, a small tributary of the mighty Taylor River rich with small brown trout. The scenery, with thick trees and cathedral cliffs jutting skyward, is gorgeous. Although the upper section of the Spring Creek plateaus into a meadow where you can fish in the open, we climbed down into the lower section, which winds between hilly ground framed by willow trees. Bart wanted the three men to experience tighter casting areas.

Vince experienced something else powerful, he told me later. “Bart picked out that beautiful little bend in the stream that looked up on an imposing mountain cliff face. A child of the Eastern Seaboard’s endless suburbia, this was really the main draw to me. The scenery was incredible. Standing in an ice-cold creek looking up at this incredible vista, like something out of a Thomas Cole painting, was more than most people can expect to enjoy in their short lives. The beer cans crammed into pockets helped, too.”

Because I was having some problems with my feet this trip, I didn’t last long wading. I handed off my fishing vest to Hunter, which elicited a cheerful “thanks, Pops,” worked my way up the steep bank, and found spots to watch them work the stream, listening to Bart encourage them.

Bart waded with them, suggesting areas to work and ways to cast. Blaz watched Bart working the creek and attempted to follow his direction.

“He was quick to identify what I was doing wrong and suggested changes to my technique,” Blaz explained later. “Once I had a decent enough an idea of what I was doing, he pointed out the spots where fish were most likely to be. I followed his lead and shortly I had a catch. If I hadn’t seen him already catch a few, I wouldn’t have the slightest idea of how to act quickly and not

miss out. Reeling in the fish was exciting, and somewhat stressful.”

Vince soon began, in his words, to get “a hang of putting the hook where I want it a solid 50 percent of the time, and eventually getting very excited about the game of fly fishing, looking for a murky or still part of the creek and trying to lay the fly in there.”

All the while, Bart urged Vince to be patient and assured him that there were plenty of fish in the creek, that although the novice may not see them, he could because his polarized glasses allow him to see more clearly into the water.

The patience and coaching paid off. “When I finally landed my first fish, pulling it in seemed like it took a long time,” he told me later. “That thing fought like hell, even if it was a tiny little brown trout.”

During floats on the Gunnison River during our men’s trip years, Bart taught me many of the same things — how to read the architecture of a river, to interpret where the fish will be, and where to present my fly. Of course, knowing and doing are two different realities.

“His coaching ability and enthusiasm helped make this a totally unique and exciting experience,” Blaz said.

I recall sitting with Bart on the banks of the East River years ago, tending our gear before a day’s fishing and talking about the joy of being in a good river.

“I like the solitude of going up a stream, casting into the ripples,” he told me as we sipped morning coffee. Bart was savoring the light delicately working its way through the cottonwoods across the way. “It’s almost meditative. I’m sitting here in front of this river early in the morning in kind of trance right now. You go through a process of stages with flyfishing. Of course, there is competitive spirit that comes out, especially when I’m fishing with my brothers. It can get intense. If someone fly-fishes long enough, he or she can’t help but know where fish live. Going down a river, it is apparent where the fly should go. But there is a spiritual aspect as well. At some point in your life, you finally realize it’s not about catching fish.”

Standing on a rise above Lower Spring Creek listening to Bart patiently coaching these three young men into catches, I was reminded that it’s about both the joy of process and the catch. And the company.

Author(R) and Bart relax and enjoy the experience of a good river