6 minute read

Deploying to Iraq: Never a Dull Moment

By Cdr. Paul McKeon

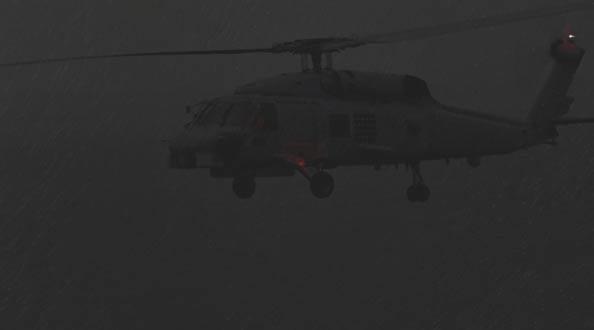

That question was my initial reaction when I was told just a few weeks before cruise that my squadron was deploying to Iraq. Since VAQ-141 is a carrier-based CVW squadron, the concept of land-basing in Iraq ran counter to all our deployment plans and our institutional knowledge as a deploying unit.

Before I even had a moment to think or react, I also was told the squadron would maintain a presence on the carrier. We would be split between Iraq and the carrier, something previously never done for any length of time in the Prowler community. While the logistics of this deployment would be complicated, my first thoughts went to how I safely would accomplish the mission under these challenging conditions. Now, months later, I can look back on our experiences to share how we addressed the challenges of this unique deployment.

The CNO has commented on the need for naval forces to be flexible and ready to move ashore, so we’re likely not the last squadron to experience the daily challenges of split-site combat operations. Here’s how we did it.

VAQ-141 was tasked to send two of our four aircraft, three out of six crews, and roughly a third of our maintainers to Al Asad Air Base, Iraq, for the duration of our deployment. The remainder of our squadron stayed on board USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71). Over about a five-month period, we flew around-the-clock combat sorties from Iraq, while simultaneously flying combat hops, unit-level-training (ULT) events, and pilot carrierqualification flights from the boat. Heavy jet maintenance, such as phase and special inspections, normally was done on the boat. Aircrew and jets regularly were rotated between Iraq and the ship. The logistics of

maintaining two sites was a daily challenge, making it critical that we factor safety into every decision.

Here are key safety and ORM issues we dealt with:

Pilot night-carrier-landing currency. I was directed by CVW-8 to maintain pilots within a 14-day window of their last night trap. This currency issue required a constant shuffling of aircraft and pilots between the ship and Iraq. Junior pilots were brought on board more frequently to give them additional day-and-night looks at the ball. Senior pilots were kept in Iraq longer because their proficiency was less affected by time away from the boat.

Pilot landing proficiency. While we generally maintained pilot currency within 14 days, our pilots were by no means proficient. Averaging about nine traps per month, there simply were not enough looks behind the boat, especially for our nuggets. To provide additional experience, trap-cat-traps were scheduled whenever possible, including at night.

ECMO boat proficiency. The side-by-side nature of the Prowler’s cockpit allows the front-seat ECMO to assist the pilot in the carrier approach and landing environment. However, with limited traps to go around, ECMO proficiency suffered in a manner similar to pilots. Junior ECMOs were given additional frontseat flights, at the expense of more senior ECMOs, to develop their boat skills and to improve their proficiency.

Flight-hour waivers. With near round-the-clock operations in Iraq, our aircrew averaged 80 to 100 flight hours per month, well above OpNavInst 3710 guidelines. With careful consultation with our flight surgeon, I issued flight-time waivers to all aircrew and closely monitored them for signs of fatigue. Because the vast majority of squadron flight time occurred in Iraq, aircrew regularly were rotated to the ship to avoid burnout. This rotation help spread out the flight time across the entire ready room.

Aircrew rotation. Because of CQ requirements and my desire to even out flight time, aircrew frequently were shuttled between the ship and Iraq. These movements carefully had to be orchestrated between the two locations to make sure crew day and crew rest were factored in. For instance, a crew in Iraq flying an early morning event might brief at 0500, fly the mission from 0700 to 1100, and then return to the boat. This crew obviously would not be a good candidate to fly a late-night mission from the boat on the same day. Short-notice rotations sometimes were unavoidable because of jet or currency issues, but these rotations were avoided when possible because they tended to disrupt daily routines. We found that publishing a spreadsheet, which showed when the rotations were to occur over the next two weeks, was the best way to add stability and certainty to people’s lives and remove a possible source of stress.

Mishap reporting and notification. Premishap binders and materials were placed in Iraq and at the boat. Because of frequent communication outages in Iraq, alternative communication paths were established. These backup communication paths made sure a mishap report and other information could be reported rapidly to the ship.

Split maintenance. A carrier-based squadron is not manned to support continuous split-site operations. We accomplished the mission by carefully balancing quals at both locations, by regularly rotating maintenance personnel, and by borrowing Sailors with selected skill levels from other squadrons. Regular rotations between the two locations also helped prevent maintainer burnout because of the heavy pace of operations in Iraq.

Maintenance documentation. Logbooks and NALCOMIS backups had to be shifted constantly as the jets moved between Iraq and the ship. Accurate maintenance documentation prevented confusion and possible safety issues generated when jets were swapped, especially when the swaps occurred on short notice.

Maintenance days. Because there were no days off in Iraq (in comparison, the ship averaged five days of port time per month), the squadron scheduled two days per month for maintenance. These days had little or no flying scheduled and allowed the maintenance det time to get caught up on accumulated up-gripes. These days also provide a breather from the near-continuous OpTempo. Similarly, aircrew were able to get caught up on paperwork, hold meetings, and take a break from flying.

This partial list of what we dealt with demonstrates the range of safety issues that must be addressed as naval aviation embraces the idea of split-based and expeditionary operations. While the challenges were new to us, and every day brought new problems, we still relied on the ORM process to make sure we were doing things in a prudent and safe manner. In the end, we safely accomplished the mission, while stretching the boundaries of what a squadron can achieve. We demonstrated once again the flexibility and power inherent in today’s naval aviation.

Cdr. McKeon is the commanding officer of VAQ-141.

One of the Navy’s and Marine Corps’ biggest challenges in embedding ORM into our culture is the name… it is called OPERATIONAL Risk Management. We want ORM to be a part of how we do business, all the time, aboard ship or at home, working or relaxing. Perhaps we should just change the meaning of the ‘O’? How about these possibilities:

• Overall Risk Management, or . . . • On-duty Risk Management, or . . . • On-deck Risk Management, or . . . • On-the-job Risk Management, or . . . • Occupational Risk Management, or . . . • Off-duty Risk Management, or . . . • Off-road Risk Management, or . . . • On-the-highway Risk Management, or . . . • Outdoor-barbeque Risk Management, or . . . • Outboard-motor Risk Management, or . . . • Off-shore-fishing Risk Management, . . . • Over-the-top Risk Management (for the X-Games wannabes), or . . . • Out-of-bounds Risk Management (for the sports nuts), or . . . • Overtime Risk Management

O _________ Risk Management . . . you fill in the blank and “just do it.”

To put ORM into practice: 1.Identify hazards or threats 2.Assess the hazards or threats to determine risk 3.Make risk decisions after developing controls 4.Implement the controls 5.Supervise and review – watch for changes

By Capt. Ken Neubauer