Winter 2023 | Volume 2 | Issue 2

BOARD OF TRUSTEES, 2023-2024

Anthony (Tony) R. Sapienza, Chair

Paulina Arruda

Christina Bascom

Ricardo Bermudez

Susan Costa

Douglas Crocker II

Betsy Fallon

John N. Garfield, Jr.

David Gomes

Edward M. Howland II

Meg Howland

James Hughes

D. Lloyd Macdonald

Ralph Martin

Eugene Monteiro

Michael Moore, Ph.D.

Gilbert Perry

Victoria Pope

Dana Rebeiro

Maria Rosario

Lucy Rose-Correia

Brian J. Rothschild, Ph.D.

Nancy Shanik

Hardwick Simmons

Bernadette Souza

Carol M. Taylor, Ph.D.

R. Davis Webb

Alison Wells

Lisa Whitney

Susan M. Wolkoff

David W. Wright

Front Cover Image: Maker once known (Niue), Hiapo detail, 1880-1890. Handmade bark cloth, 68 x 88 inches, New Bedford Whaling Museum, 00.200.452.

Back Cover Image: Advertisement from the New Bedford Portuguese-language newspaper Progresso, vol 12, no. 48 (January 6, 1906), NBWM, 2023.58. Gift of Rita Pacheco.

Vistas: A Journal of Art, History, Science and Culture

Copyright © 2024 New Bedford Whaling Museum

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in reviews and certain other non-commercial used permitted by copyright law.

18 Johnny Cake Hill New Bedford, MA 02740 www.whalingmuseum.org

President & CEO

Amanda McMullen

Design and Production

Brian Bierig, Graphic Designer

Consulting Editor

Naomi Slipp

Photography

Melanie Correia

Editor

Michael P. Dyer

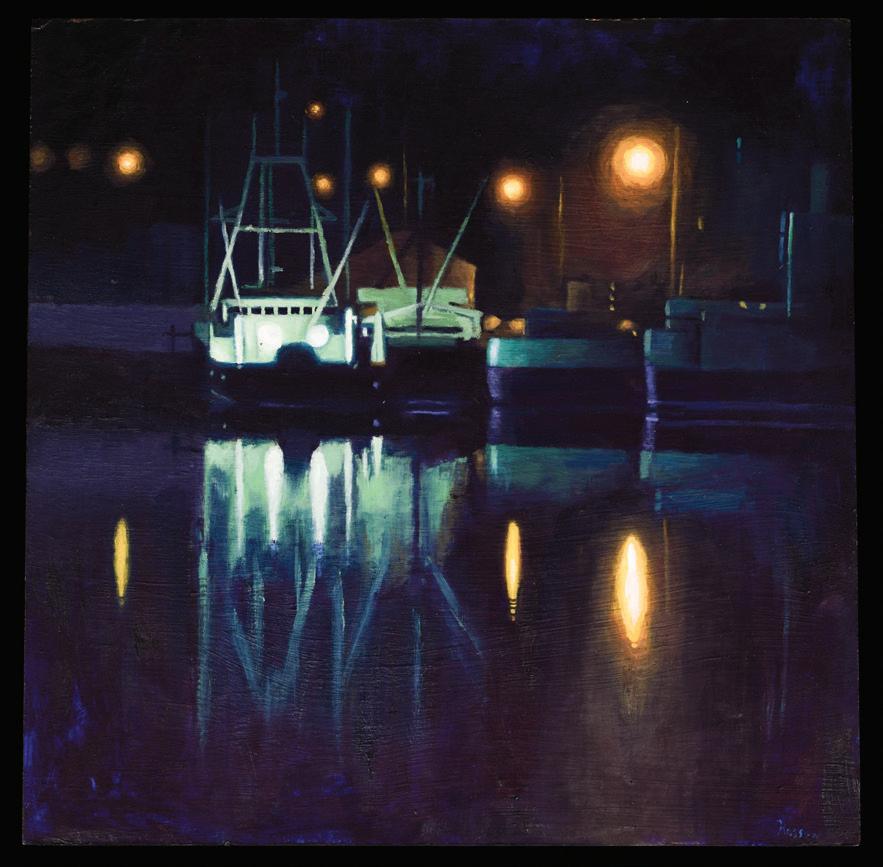

Publisher

New Bedford Whaling Museum

Scholarship & Publications Committee

Michael Moore (Chair)

Mary Jean Blasdale

John Bockstoce

Mary K. Bercaw-Edwards

Tim Evans

Ken Hartnett

Judy Lund

Daniela Melo

David Nelson

Victoria Pope

Brian Rothschild

Tony Sapienza

Jan da Silva

Issue

Winter 2023 | Volume 2 |

2

1 | Winter 2023

Maker once known, Maria Beckley Fleetwood with her children Anne and Solomon, c. 1853. Sixth plate daguerreotype, NBWM 1940.24.109.

2 Contents Foreword ............................................................ 3 Mercer’s Legacy Recovering Narratives about the Whaling Collection at the Mercer Museum By Peter Glogovsky, Ph.D. 5 A Record of Life and Encounter A Hiapo from Niue By Ymelda Rivera Laxton ....................................... 13 A Life of Courage, Integrity, and Purpose By Samantha Santos 19 Whaling Journals as Dream Diaries By Mark D. Procknik 21 From the Page: Transcription Stories By Naomi Slipp ...................................................... 23 The Wider World & Scrimshaw ........ 25 The Daguerreotype and Ambrotype in New Bedford By Marina Dawn Wells ........................................... 29 An Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) Grant Improves collections preservation & access By Michael P. Dyer ................................................. 35 The Conservation of Charles Sidney Raleigh’s Panorama of a Whaling Voyage By Jordan Berson .................................................... 41 The Complex Stories of Seals and Society By Andrea Bogomolni ............................................ 45 The Stars That Guide Us Roy Rossow’s Inspiration By Emily Reinl 49 "Harboring Hope": the Importance of Multiple Perspectives By Karissa Walker 51 Looking Back ................................................ 55 Winter 2023 | Volume 2 | Issue 2

Foreword

All too often we place a future value on the concept of “discovery.” What new invention will change our lives; what next daring innovation will alter our tomorrow? The beauty in history is the discovery that comes from looking at yesterday. I was struck by the abundance of discovery laced throughout the contributions in this issue of Vistas.

As you dive into these pages, enjoy learning about a hiapo from Niue in our collection from our Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art & Community Projects, Ymelda Rivera Laxton. She so effectively chronicles all that we can understand of this traditional cloth made from bark; but her essay also illuminates that we can’t ever possibly know everything for certain. So often we work from whispers of yesterday to piece together the narrative. Connecting these dots inspires our team and the many scholars who study our collection.

You may also be equally spellbound by the deep dive from our Photography Collection Curatorial Fellow, Marina Dawn Wells, who shares revelations gathered from more than a year spent understanding and cataloguing our robust photography collection. Seamlessly weaving together a summary of a centurylong span of this portion of our collection, they detail the emergence of this art form and the accessibility it brought. If you have ever sat down to thumb through an old family album, you can relate to the many moments of detection and connection elicited by this work.

Samantha Santos, who has played a key role at the museum in guiding our High School Apprentices, notes her own discovery of Captain Paul Cuffe, an individual of extraordinary contribution to our immediate community and beyond. And yet growing up here she had never known of him before.

Museums and historical societies have a profound responsibility to not only care for our collections, but to bring these stories to you. Offering visitors, scholars, and students a chance for their own discovery is what guides us. Settle in to this edition of our journal dedicated to examinations across art, history, science, and culture. I know there will be many discoveries for you on the following pages.

Amanda McMullen President & CEO New Bedford Whaling Museum

3 | Winter 2023

4

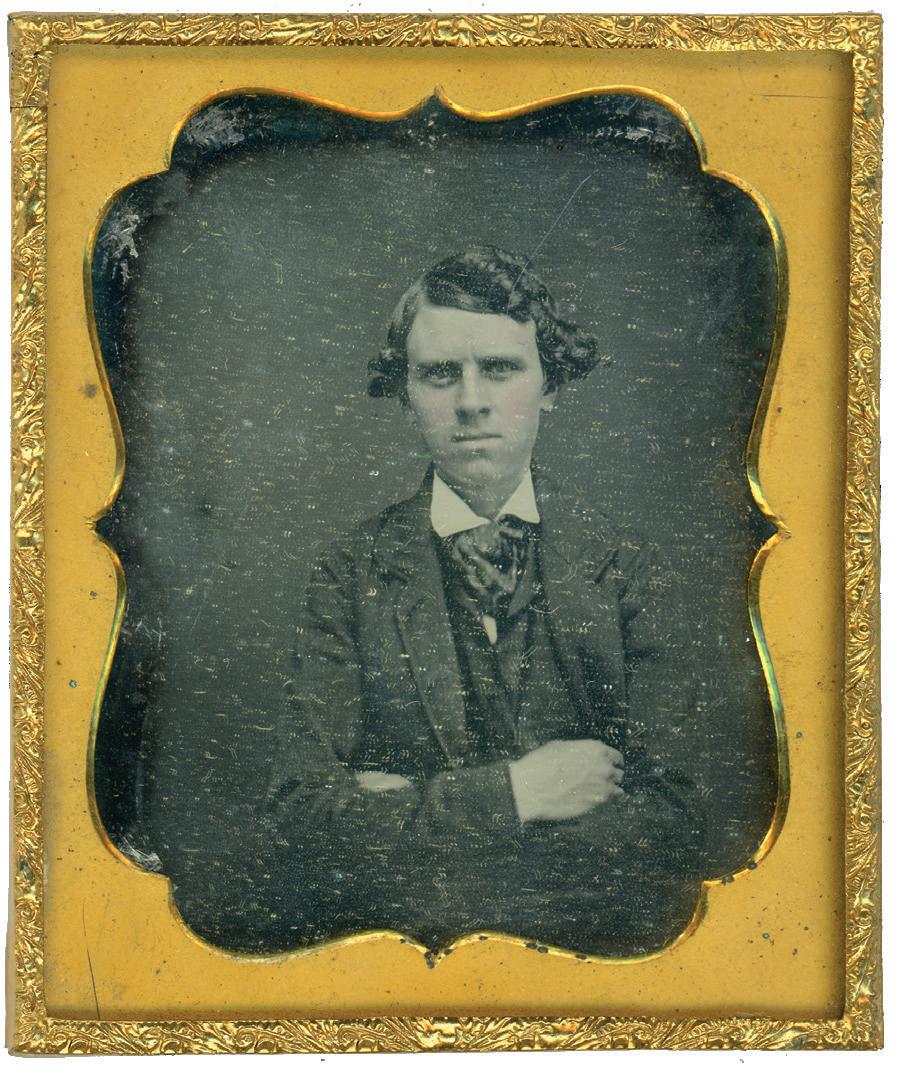

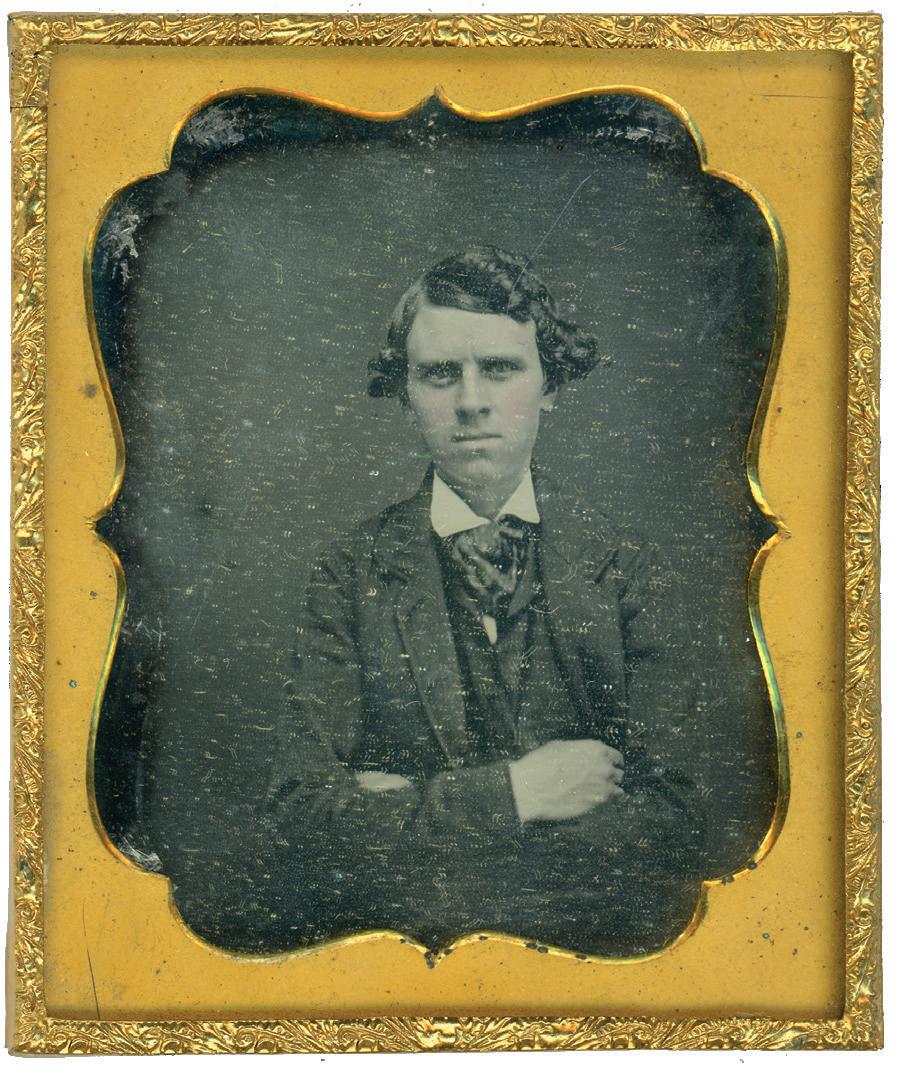

Charles H. Williamson, Jamie McKenzie, 1856. Sixth plate daguerreotype, NBWM 1980.33.9.1.

Feature Articles

Mercer’s Legacy:

Recovering Narratives about the Whaling Collection at the Mercer Museum

Peter Glogovsky, Ph.D., Project Assistant

The Mercer Museum & Fonthill Castle, operated by the Bucks County Historical Society

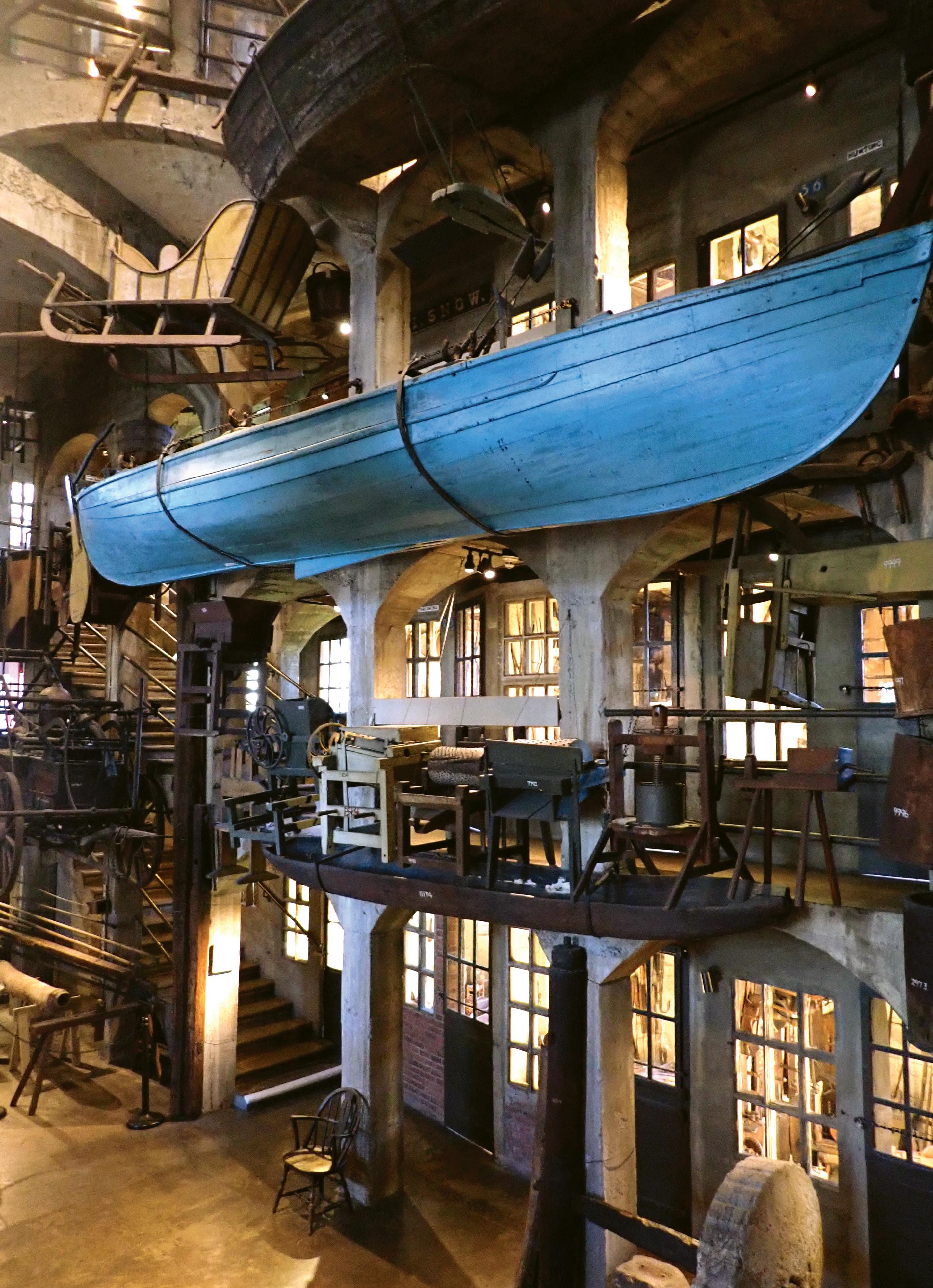

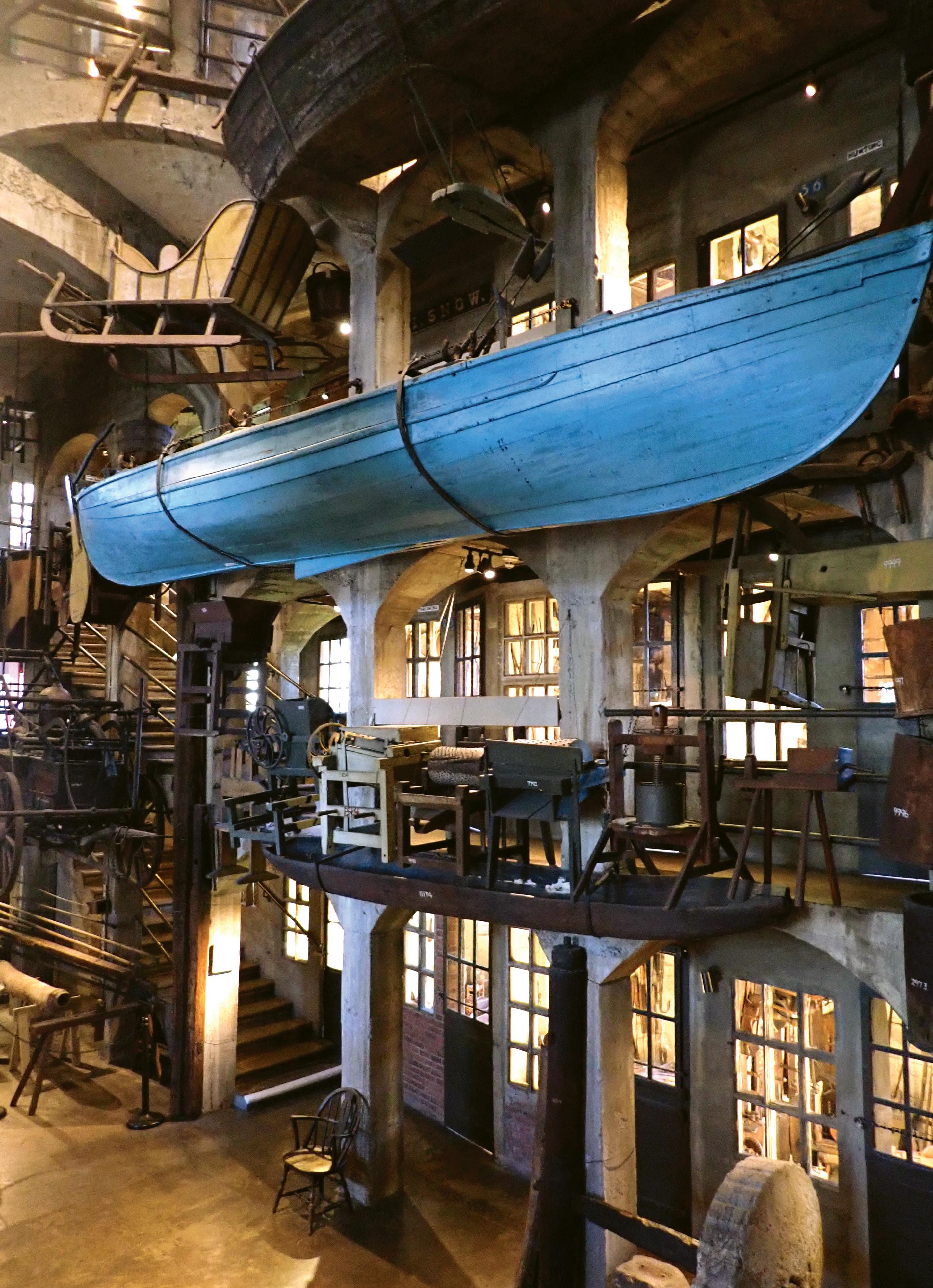

In October 1907, Henry C. Mercer (18561930) acquired a completely outfitted whaleboat (#1945) from the J. & W.R. Wing & Company, New Bedford, Massachusetts. Brothers Joseph Wing (1810-1895) and William R. Wing (1830-1908) of Dartmouth, MA, established the firm in 1849.1 From 1860 to 1910, the company managed one of the largest whaling fleets of the American whaling industry. After Mercer purchased the boat and whaling equipment, he donated the collection to the Bucks County Historical Society. When the new, poured concrete Mercer Museum, in Doylestown, PA was completed in 1916, the boat was suspended from the fourth level of the central court. Much of the whaling equipment that was procured at the time was either placed into the boat itself, along the fourth-level gallery, or into the maritime exhibit in Room 34.

When Henry Mercer acquired the whaling collection and shipped it to Doylestown, little to no provenance about the objects was recorded. The Bucks County

1 “Historical Note,” Mss. 35 J. & W. R. Wing & Company Records, 1833-1918. New Bedford Whaling Museum Research Library, https://www.whalingmuseum.org/collections/highlights/ manuscripts/mss-35/, accessed March 22, 2023. The firm of J. & W. R. Wing was first established as a clothier and outfitter. They acquired their first whaler, the bark John Dawson in 1853, and the bark Osceola 2nd in 1854 as sperm and right whalers on voyages to the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans. In addition to managing whaling vessels, New Bedford whaling merchants, like the Wing brothers, commonly operated other supply or processing businesses directly associated with a functioning whaling port including as grocers, tailors, ship chandlers, lumber yards, nail factories, shipyards, oil refineries, or candle houses.

Historical Society (BCHS) accession ledgers record almost no information about the purchase of the collection, the origin of this whaleboat, which whaleship the boat was used on, or who built the craft. Recovering the provenance of the collection, together with the stories of the individuals whose livelihoods depended upon it, and sharing these stories with the public is essential for the Mercer Museum to fulfill its mission.2

In 2022, the Institute for Museum and Library Services (IMLS) awarded a grant to the Mercer Museum & Fonthill Castle. This grant provided resources to museum staff to clean, document, and research nearly 500 objects located in the original core of the museum. This grant project is the first phase in a long term plan by the Mercer Museum to revise and update interpretation methods and materials. Vice President of Collections and Interpretation Cory M. Amsler, Collections Manager Kristin Lapos, Assistant Collections Manager Emma Falcon, Exhibition Specialist and Preparator Clint Flack, and Project Assistant Peter Glogovsky compose the project team. As part of this broader project the whaleboat and the equipment displayed inside were cleaned and documented in March 2023. The remainder of this article reviews the historical context of the collection and how it was rediscovered.

2 The mission of the Mercer Museum is: “To educate and engage its many audiences in appreciating the past and to help people find stories and meanings relevant to their lives—both today and in the future.”

5 | Winter 2023

Figure 1. Central court of the Mercer Museum with whaleboat, photograph by author, March 2023.

Figure 1. Central court of the Mercer Museum with whaleboat, photograph by author, March 2023.

When visitors enter the central court space and see the whaleboat above their heads, they often ask about its origin. Prior to the work by the project team, staff could only explain that the boat came from New Bedford and was part of the whaling fleet owned by the J. & W.R. Wing & Co. We now have more information. While cleaning the boat the project team identified a mark “LEONARD” branded into a board at the stern.3 When a whaleboat was completed, some boat shops burned their mark into the wood at the stern or sometimes near the

bow.4 Finding this brand was an important piece of information as it confirms that this whaleboat was constructed at the boat shop of Ebenezer Leonard (1814-1891) in Acushnet, Massachusetts.5

Ebenezer Leonard was born in Taunton, Massachusetts, on April 10, 1814. In 1827, he entered the boat building trade as an apprentice

4 Ansel describes a similar brand used by Charles Beetle to burn a mark into the wood of the lion’s tongue and inside of the thigh board. Willits D. Ansel, Whaleboat: A Study of Design, Construction and Use from 1850-2014 (Mystic: Mystic Seaport, Inc. 1978; 2014 ed.), 82-83; Michael Dyer, email message to author, March 21, 2023.

3 This board, commonly termed the “lion’s tongue,” is a lateral strengthening hardwood member through which the oak “loggerhead” was mounted.

5 Michael Dyer, email message to author, March 21, 2023; “Ebenezer Leonard” in Franklyn Howland, A History of the Town of Acushnet, Bristol County, State of Massachusetts (New Bedford: published by the author, 1907), 313; “Ebenezer Leonard” Year: 1880 ; Census Place: Acushnet, Bristol, Massachusetts ; Roll: 522; Page: 13A; Enumeration District: 063. Ancestry.com.

7 | Winter 2023

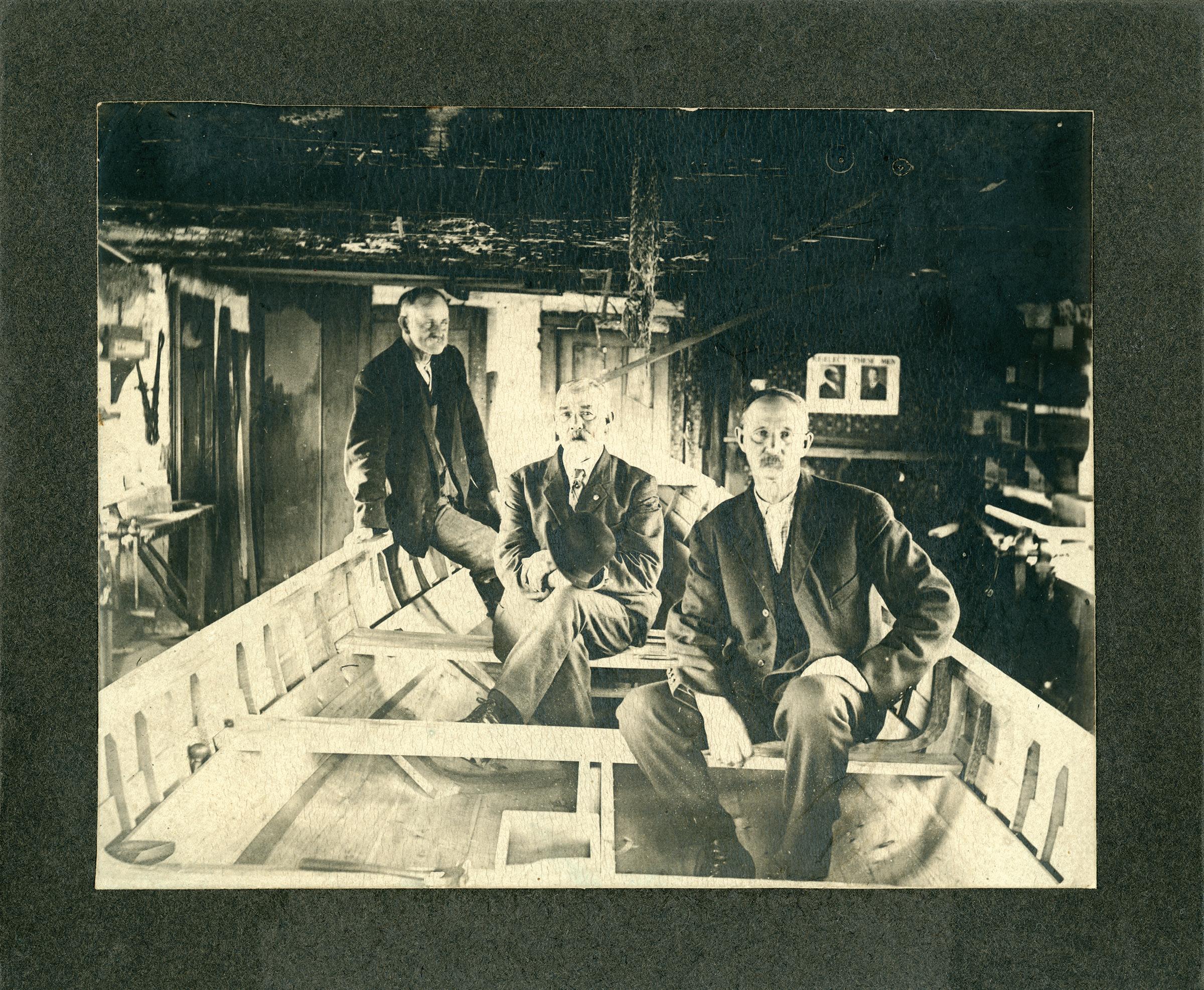

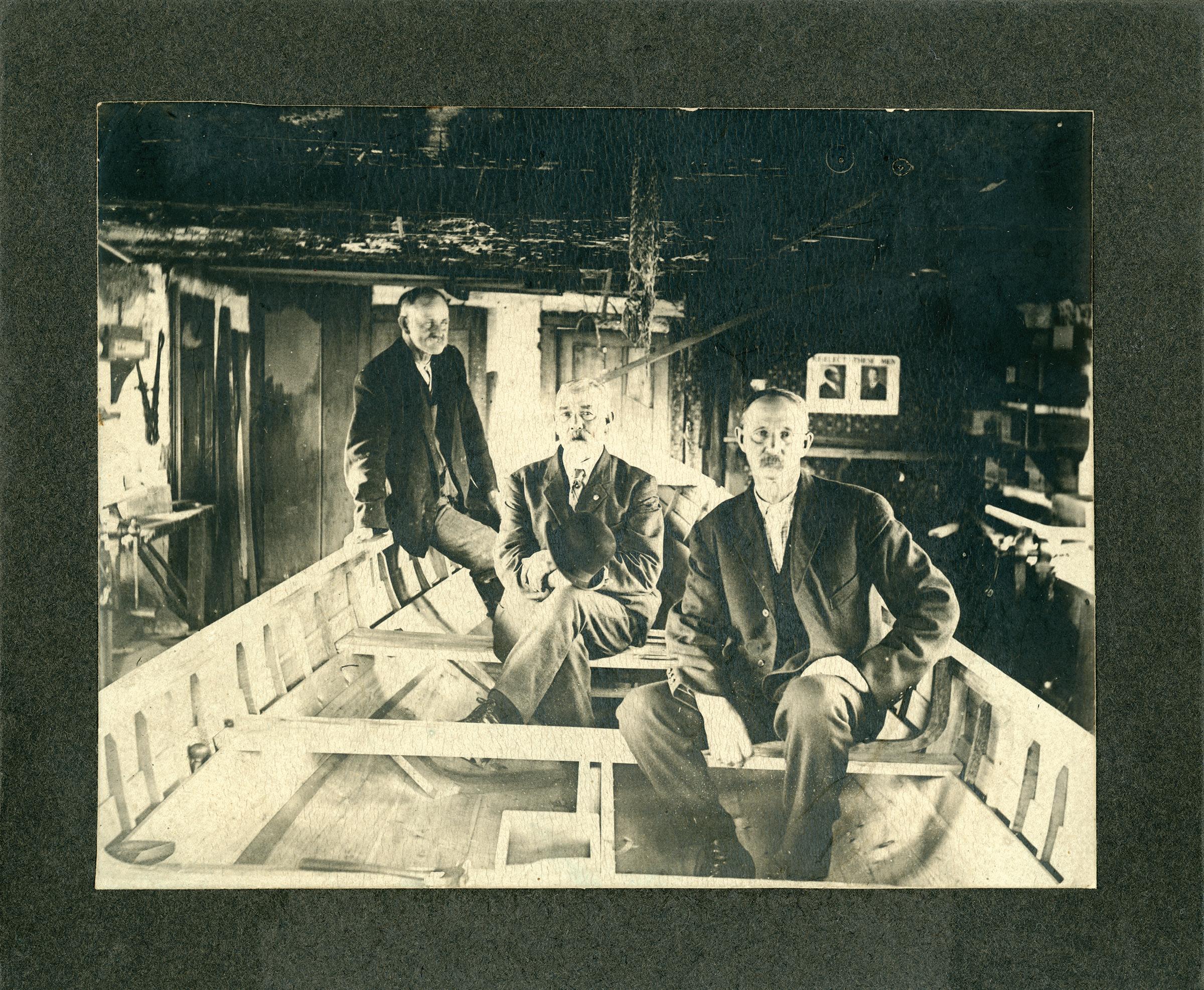

Figure 2. Ebenezer Leonard with his sons Charles and Eben Jr. around 1890. Photograph, Collection of the New Bedford Whaling Museum, New Bedford, MA, 2000.100.3437.

at William E. Carver’s shop at New Bedford.6 As a journeyman, Leonard worked with other New Bedford boat builders including Jethro Coffin and later, for several years, Daniel Wadsworth. In 1851, Leonard relocated to the nearby town of Acushnet, where he continued building boats until his death in 1891. Leonard’s sons Eben F. and Charles learned the trade from their father as apprentices in the shop. Following their father’s death in 1891, the sons continued the family business into the early twentieth century.7 Eben F. and Charles, who operated the boat shop from 1891 until 1907, most

6 “Acushnet” in Duane Hamilton Hurd, History of Bristol County, Massachusetts: With Biographical Sketches of Many of Its Pioneers and Prominent Men (Philadelphia: J. W. Lewis & Company, 1883), 163. Carver’s shop was located at the rear of 40 South Water St., New Bedford.

7 Hurd, History of Bristol County, Massachusetts, 163.

likely constructed this boat.8 Today the brand on the lion’s tongue is barely visible beneath layers of paint, but it is a reminder of the craftsmanship and personality invested into these boats.

The use of this boat and its equipment was ascertained after a number of objects carrying the letters “SB” were found in the collection. The two letters are an abbreviation for “starboard boat.”9 Whaleships carried several whaleboats aboard and pieces of equipment were commonly marked to indicate to which boat these objects belonged.10 A number of objects in the

8 Howland, A History of the Town of Acushnet, 313.

9 Mark Procknik, Email message to the author, March 1, 2023; Mark Procknik, Email message to the author, March 7, 2023; “Whalecraft Markings,” Whalesite.org, Thomas G. Lytle, https://whalesite.org/ whaling/whalecraft/, accessed March 3, 2023.

10 Equipment carried the initials of the boat it belonged to: S.B.B. Starboard bow boat; S.B. Starboard boat;

8

L.B. Larboard boat; W.B. Waist boat; P.B.B. Port bow boat. Ansel, The Whaleboat, 99.

Figure 3. Photograph of the A.R. Tucker, undated, possibly from her 1901-1903 or 1903-1906 voyage. Photograph, Collection of the New Bedford Whaling Museum, New Bedford, MA, 2000.100.488.

collection have these letters: Two line tub covers, a “piggin” or small pail, several short paddles, and a lantern keg. There are likely more objects in this collection marked with SB lettering which have not yet been identified. After a cursory search, the project team only found the letters SB painted, carved, or stamped on the equipment. As there were no other markings found, such as WB or LB, it is reasonable to argue that most, if not all, of the equipment in this collection came from the same starboard boat, rather than having been assembled from multiple boats.

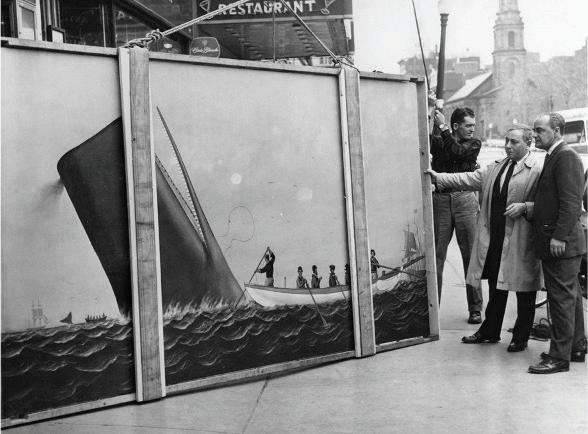

More compelling to visitors and staff alike are markings found on two harpoons and two knives bearing the letters BK ART and B ART, along with SB, that unite this whaleboat to a particular whaleship, the bark A.R. Tucker (1851-1908). After reviewing a list of vessels owned by the J. & W.R. Wing & Co. and scrutinizing the chronology of these vessels against the date of the collection purchase, the A.R. Tucker was the only whaleship whose full name, abbreviated form, and span of life most prominently aligns. Further, the chronology of this whaleship and her voyages, discussed later in this article, is consistent with the sequence of events related to the purchase of the whaleboat. Adding further credence, no other letters were found on the whaling equipment that would otherwise indicate that the equipment and boat were removed from another whaleship. Two toggle head whale irons and two knives are perhaps the strongest material evidence that link this boat and the equipment to this particular ship.11

The project assistant consulted with Michael P. Dyer, Curator at the New Bedford Whaling Museum, about these markings on both the equipment and the boat itself. Dyer confirmed that the whaleboat was the starboard whaleboat from the bark A.R. Tucker He also suggested that the starboard boat in an undated photograph appears clean and undamaged and may possibly be the very same whaleboat subsequently acquired by Henry Mercer in 1907. Further research into the context of this photograph and the other materials in this collection may confirm this perspective.

The bark A.R. Tucker (1851-1908) was a purpose-built whaler constructed at Dartmouth, Massachusetts in 1851 at the yard of Alonzo Matthews and John Mashow. Mashow (1805-1893) was the famed African-American shipwright who was born enslaved and somehow re-located from South Carolina to Dartmouth as a youth around 1818. He went on to become part-owner of the shipyard and the builder of many famous whale ships. The A.R. Tucker was registered in June of that year to Abner R. Tucker and Thomas S. Bailey, who also served as master on her first voyage.12 The A.R. Tucker made a series of voyages during the height of the American whaling industry and, in 1861, J. & W.R. Wing & Co. bought her.13 The ship was registered as completing twenty-four whaling voyages, each of which lasted from only a few months to upwards of four years. The final voyage of the A.R. Tucker was from October 1903 to July 1906.14 In 1908, the whaleship was sold and broken up and it was during these years that Mercer acquired the whaleboat and its gear.

The A.R. Tucker was designed and built as a bark, a sailing vessel that featured three masts, in which the foremast and mainmast were square-rigged while the mizzen mast at the stern was fore-and-aft rigged.15 Barks were easier to handle, required a smaller crew,

12 “A.R. Tucker.” American Offshore Whaling Voyages: A Database, Mystic Seaport Museum, Inc. and New Bedford Whaling Museum, https://whalinghistory.org; “A.R. Tucker ” Ship Registers of New Bedford, Vol. 3 1866-1939, Survey of the Federal Archives Division of Professional and Service Projects, Works Progress Administration, 1940.

13 For a complete list of other owners and masters for the ship, from 1851-1906, see “A.R. Tucker” in Ship Registers of New Bedford, Vol. 2 1851-1865, and Ship Registers of New Bedford, Vol. 3 1866-1939. Survey of the Federal Archives Division of Professional and Service Projects, Works Progress Administration, 1940.

14 A full list of the whaling voyages for the A.R. Tucker can be found on American Offshore Whaling Voyages: A Database, Mystic Seaport Museum, Inc. and New Bedford Whaling Museum, https://whalinghistory.org, accessed March 23, 2023.

15 “Whaling History: Vessels and Terminology” New Bedford Whaling Museum, https://www.whalingmuseum.org/learn/research-topics/ whaling-history/vessels-and-terminology/, accessed March 23, 2023.

9 | Winter 2023

11 The stamp found on (#12178), MACY, indicates that this harpoon was forged by Edwin B. Macy, or his brothers, New Bedford, MA.

and became one of the most popular vessels employed by whaling fleets after the mid-1800s.16 The A.R. Tucker was recorded as being one of the smallest of the New Bedford whalers at 145 tons with a length of 92 feet.17 She carried at least three whaleboats: the larboard boat, the waist boat, and the starboard boat.

One or two extra boats were stowed on deck skids.18

To understand the context of Henry Mercer’s October 1907 acquisition of the whaleboat and whaling equipment from the J. & W.R. Wing & Co., it is important to recognize that the last years of the A.R. Tucker sequentially align with the time of Mercer’s purchase. Although the specific voyage or voyages upon which this whaleboat saw service is yet undetermined, enough is known so as to put together a rough sketch.

The final whaling voyage of the A.R. Tucker was from October 3, 1903 to July 30, 1906. Sylvanus B. Potter was the master of the ship on this final sperm whaling voyage to the Atlantic Ocean returning 300 barrels of sperm oil, having transshipped home 1350 barrels during the voyage.19 After her return, the ship was moored in New Bedford for a period of time, remaining under the management of the J. & W.R. Wing & Co.

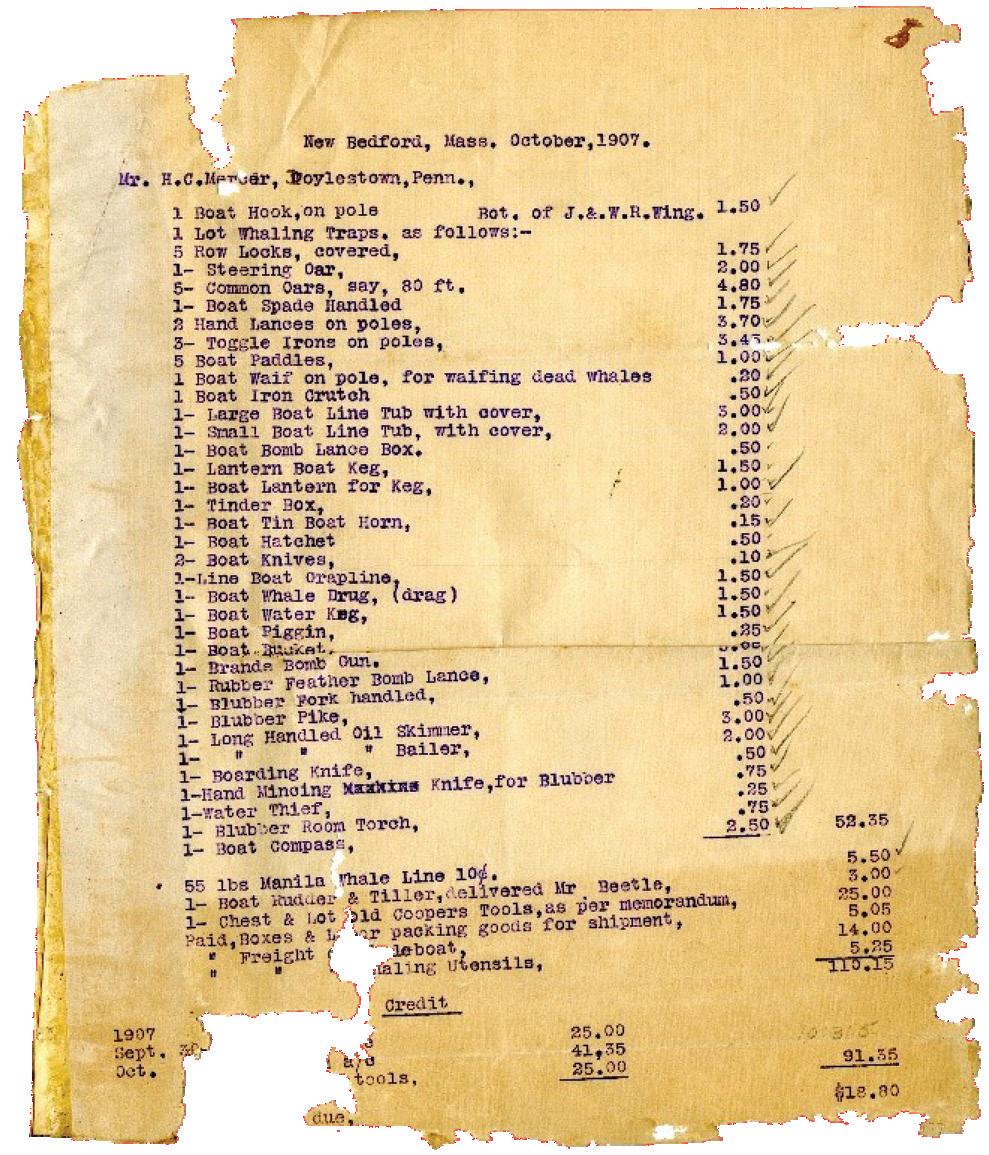

In September 1907, Henry Mercer communicated

16 Paul Giambarba, Whales, Whaling, and Whalecraft (Centerville, MA: Scrimshaw Press, 1967), 42.

17 “A.R. Tucker” in Ship Registers of New Bedford, Vol. 2 18511865,1940; Dimensions and tonnage of the ship, recorded in 1851, were as follows: 218 5/95 tons, length 95 ft. 1 ½ in., breadth 23 ft. 1 in., depth 11 ft. ½ in.; When the ship was re-registered in 1865, the dimensions and tonnage were listed as follows: 129.95 tons, length 92.4 ft., breadth 23.2 ft., depth 11ft. In 1876, the ship was re-registered as being 145.36 tons. One newspaper article cited, “Smallest of her rig on the coast is the A.R. Tucker, a New Bedford whaler, of 145 tonnage and 92 feet in length, built in Dartmouth, Mass.” “Largest and Smallest,” The Pittsburgh Press (April 14, 1907).

18 See entries in Journal of the A. R. Tucker (Bark) out of New Bedford, MA, mastered by Asa Grinnell and kept by Alonzo Peirce, on a whaling voyage between 1861 and 1864, InternetArchive.org, accessed March 29, 2023.

19 1670 barrels sperm oil total catch of the voyage as reported on American Offshore Whaling Voyages: A Database, Mystic Seaport Museum, Inc. and New Bedford Whaling Museum, https://whalinghistory.org, accessed March 23, 2023; 300 barrels sperm returned as reported by The Whalemen’s Shipping List and Merchants’ Transcript, New Bedford, MA (April 9, 1907).

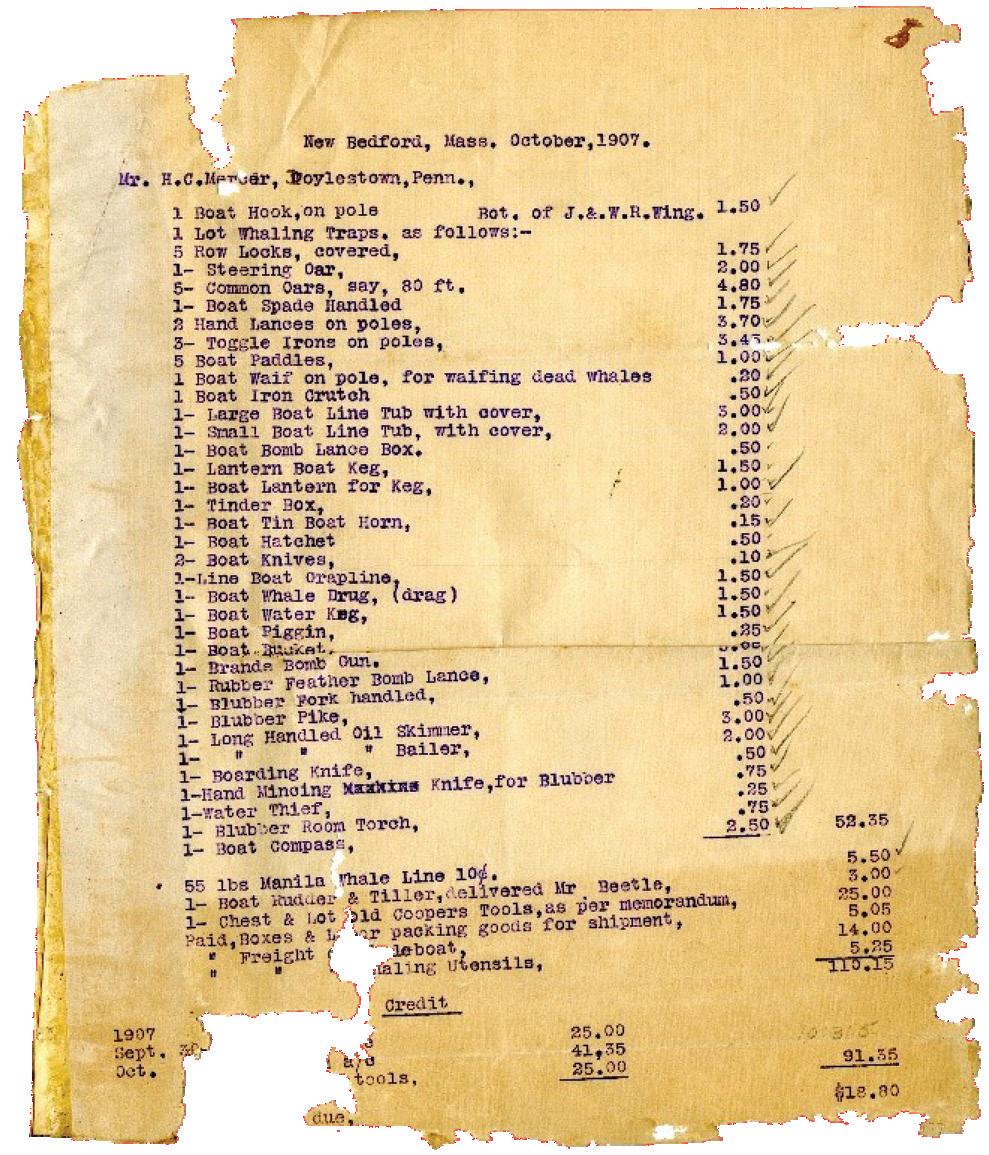

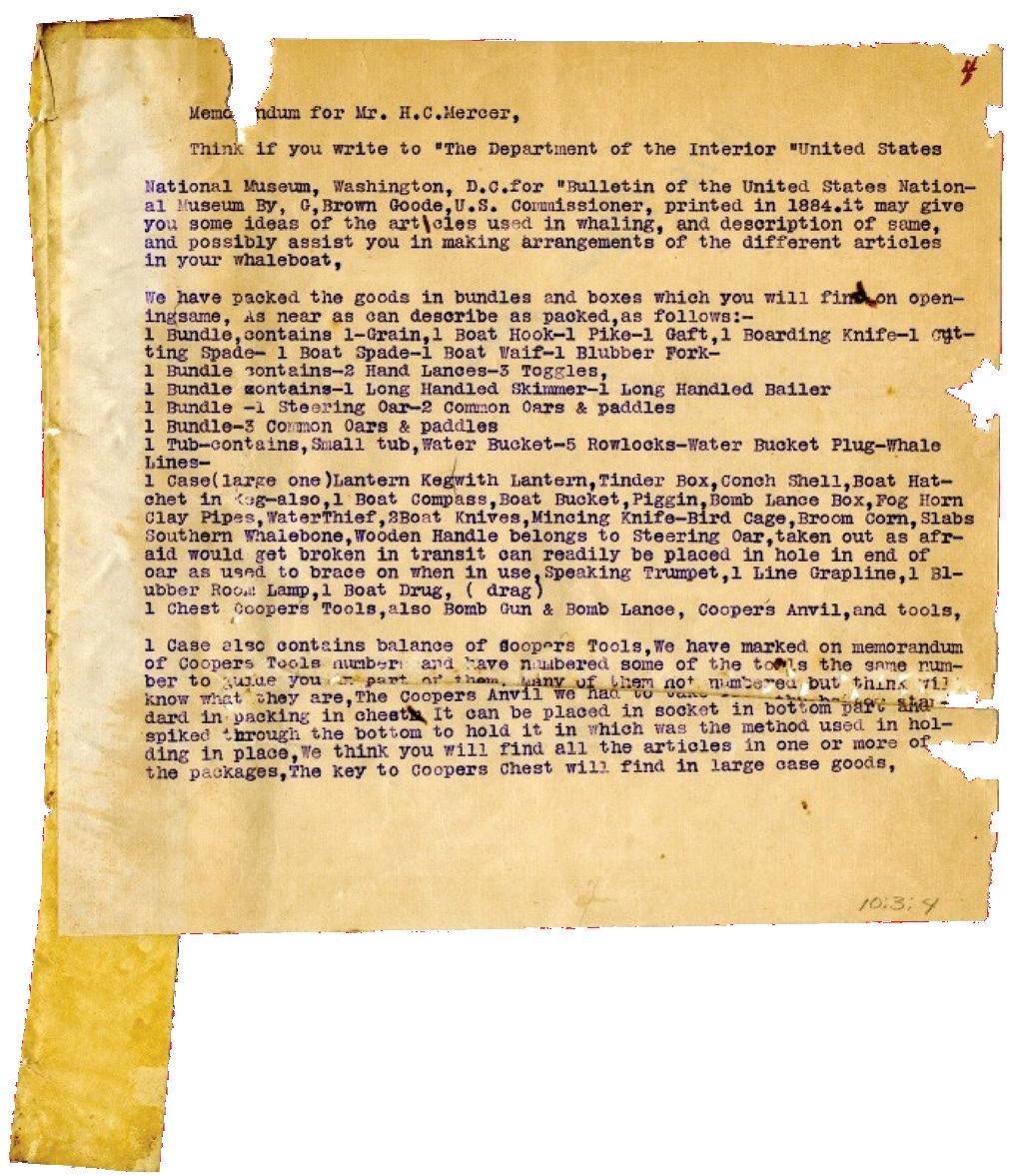

with William R. Wing about purchasing a completely equipped whaleboat. Multiple lists of whaling equipment were drawn up and correspondence shows that there was some negotiation about which objects Mercer desired and for what price. No documentary evidence has yet been found that suggests the J. & W. R. Wing & Co. publicly auctioned off equipment from the A.R. Tucker. How exactly Mercer heard about the whaleboat and equipment remains uncertain. With the transaction complete, on October 16, 1907, the boat and fittings, along with equipment used aboard the whaleship to render blubber into oil, were shipped to Doylestown, Pennsylvania, addressed to Henry Mercer. Some of the whaling equipment was crated while other tools were shipped in bundles. The whaleboat itself, weighing around 1000 pounds, was sent on a railcar.

The whaleship remained moored until she was “sold and withdrawn” from the whaling fleet on June 18, 1908.20 There are no subsequent references to the whaleship in The Whalemen’s Shipping List and Merchants’ Transcript after this date.21 By this time, at least some of the shipboard equipment and boats were sold to various parties. The managing owner, William R. Wing sold “the hull, rigging, and other parts of said vessel now attached to her as lays at Central Wharf” to New Bedford junk dealer Herbert L. Jones.22 Presumably most of the fittings and equipment were already removed from the ship.

It is not known where the whaleboat and equipment were stored when the collection first arrived in Doylestown. Over time, each object in the collection was assigned an object number and accounted for in the Bucks County Historical Society accession

20 The Whalemen’s Shipping List and Merchants’ Transcript, New Bedford, MA (June 23, 1908).

21 “A.R. Tucker” in Ship Registers of New Bedford, Vol. 2 1851-1865 and Ship Registers of New Bedford, Vol. 3 1866-1939. Survey of the Federal Archives Division of Professional and Service Projects, Works Progress Administration, 1940.

22 Mark Procknik, Email message to author, April 8, 2023; Letter, William R. Wing, June 18, 1908, MSS 35, J. & W.R. Wing & Company Records. New Bedford Research Library. See: New Bedford City Directory (Boston: W.A. Greenough & Co., 1906), for reference to Herbert L. Jones.

10

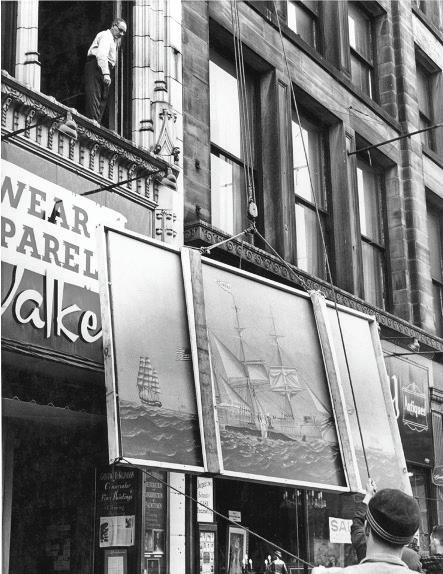

ledgers.23 In 1916, when the new museum was nearing completion, the boat was suspended from the fourth floor of the central court using block and tackle. Other large objects were added to the interior at the same time, including a Conestoga wagon and a stagecoach. Some of the whaling equipment that

23 Note that the object numbers are not sequential for the whaling collection. The whaleboat is #1945, while the killing lances are #12177 and #12180. The short paddles range from #14275#14279, and the bomb or darting gun is #8678. This indicates that the collection was accessioned in batches at a later point after arrival.

hull of the boat, while other pieces were displayed in Room 34, the maritime exhibit room.

Based on this information, a general history of the whaling collection at the Mercer Museum can now be relayed to the public. However, the specific voyage on which this boat was used remains undetermined. One possible avenue to solve this might be to examine a series of uniform notches carved into the loggerhead. The loggerhead was a round wooded post, generally a

11 | Winter 2023

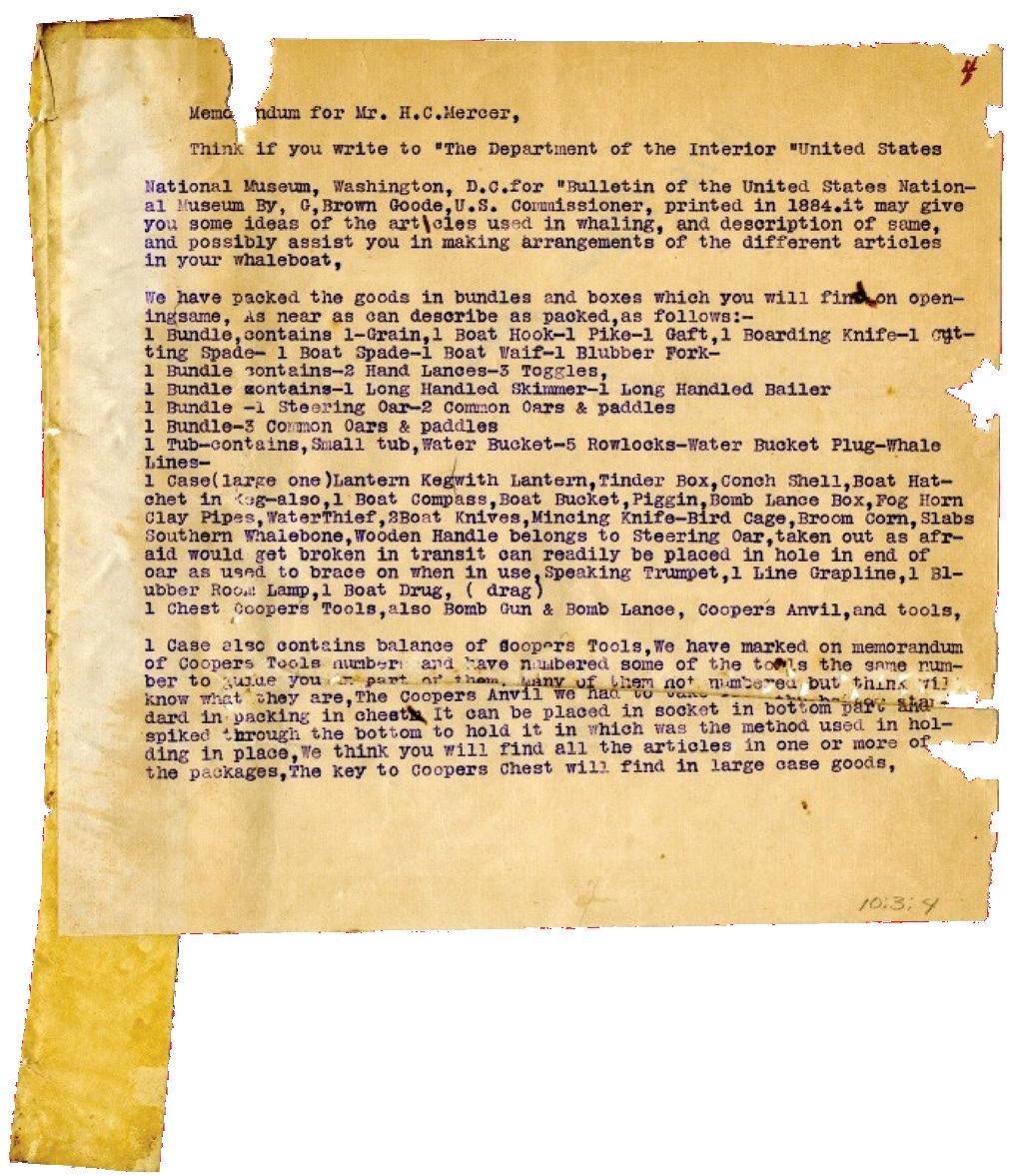

Figure 4 and 5. Shipping Receipt (left) and Memorandum (right) October 1907, MSC 291 Mercer More Misc. Loose Ends/Stray, Upper Vault, Rank 62, Shelf 7, Papers Relating to Acquisition of Whaleboat & Other Items Series 10, Vol. 3. From the Collection of the Mercer Museum Research Library of the Bucks County Historical Society.

full-round trunk of a young white oak tree, mounted on the starboard side of the stern platform. The harpoon line wrapped twice around the loggerhead and was controlled as it ran out from the tubs to the bow chocks.24 There are twelve uniform notches cut into the loggerhead that indicate the completion of several successful whale hunts for the crews of this particular boat. Nine of these notches are located on the outside rim of the loggerhead, and three more notches located on the top of the post.

These notches can conceivably be used to link this boat to a specific multi-year voyage aboard the A.R. Tucker. The notches on the loggerhead are a tangible record of the number of whales killed by the boat crew and capture the imagination.25 By comparing the number of notches on this loggerhead to logbook entries of the A.R. Tucker, it might be possible to link this boat to a specific voyage or series of voyages. However, this is difficult to accomplish solely using the loggerhead notches as evidence. Current speculation is that the boat likely came from the last two voyages of the A.R. Tucker in either 1901 or 1903. Corresponding documentary evidence in logbook entries would confirm whether the notches match with an exact number of whales that this boat crew captured during a voyage.

The short lifespan of whaleboats, in general, makes it reasonable to believe that the Mercer Museum whaleboat came from a period closer to the disuse of the A.R. Tucker. The useful life of a whaleboat was determined by several factors, including the length of the voyage itself. George Brown Goode wrote of the construction and longevity of these craft in 1884, “some vessels return with the same boats they took out, which have, however, undergone many repairs during the voyage; but usually the boats are so much disabled in the service as to render substitutes imperative.”26 Although whaleboats were constructed

24 For a full description of loggerheads, see Ansel, The Whaleboat, 47.

25 Michael Dyer confirmed that similar notches were also found on the loggerhead of a whaleboat at the New Bedford Whaling Museum. Michael Dyer, Email message to author, 3/21/23

26 James Temple Brown, “Chapter 2: The Whalemen, Vessels and Boats, Apparatus, and Methods of the Whale Fishery,” in George Brown Goode, The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States (Washington: The Government Printing Office, 1884), 242.

to be strong yet lightweight, they were also built to be low cost for their owners. To an extent, these boats were understood to be expendable as “most boats stood the abuse for about one voyage” which could last up to four years.27 This particular whaleboat exhibits evidence of damage to its hull in two locations and wear patterns from hard use elsewhere. At least one repair was made to the hull using a canvas patch while there is a second noticeable location where a section of hull planking is missing near the keel. It is possible that this boat survived multiple whaling voyages. However, given the demands and conditions that a boat encountered during even a single voyage, it is far more likely that this boat dates from the later voyages of the A.R. Tucker in 1901 or 1903.

The whaleboat is iconic as it dominates the central court space at the Mercer Museum. Since its opening in 1916, the Museum’s whaleboat and whaling collection have contributed greatly to the visitor’s complete experience, being a way for visitors to appreciate the cultural history of the U.S. commercial whale fishery of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The material and archival evidence that contributed to the re-discovery of this collection’s provenance was neither the initial objective nor the outcome anticipated by the project team. Although significant, the research presented in this article is only a starting point. More will be done to design and implement appropriate interpretation to enhance the visitor experience while maintaining scholarly excellence and information retention. The whaling collection offers several potential paths for interpretation including the recovery of historical narratives about the individuals who built this boat, and the industry and its participants that depended upon it for their livelihoods. This whaling collection in a Pennsylvania museum emphasizes how Henry Mercer’s vision and legacy continues to shape how both visitors and staff members engage with the past.

27 Ansell writes, “whaleboats were built cheaply and quickly. It was expected that they would be used hard, become racked and battered, and be disposed of before rot or rusting fastenings destroyed them.” Ansel, The Whaleboat, 39.

12

A Record of Life and Encounter: A Hiapo from Niue

By Ymelda Rivera Laxton, Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art & Community Projects

The New Bedford Whaling Museum holds some thirty pieces of decorated barkcloth from various cultures of Oceania including a superb example from the island of Niue. This cloth, commonly called tapa, is made from bark that has been softened through a process of soaking and beating. It is a versatile fabric crafted and used by communities in the Oceanic islands for clothing, mats, memorial and sometimes ceremonial purposes. The bark, harvested from several types of trees and shrubs, often mulberry and fig, is pulled off in a single sheet and the inner bark soaked to soften the material. Inks made from the soot and oil of nuts like the candleberry nut are used to paint the cloth.

Hiapo are most often created by one maker or family and are regarded as an art form historically crafted by women.1

Though tapa is the umbrella term used for decorated barkcloth across Oceania, each individual community uses their own word for the craft. In Niue, the cloth is called a hiapo. Many documented hiapo surviving today were made between 1880 and 1900.2 The bark cloth featured here was most likely made in this same time period. Niue is located in a triangle

1For reference, see: Roger Neich and Mick Pendergrast, Traditional Tapa Textiles of the Pacific (London: Thames and Hudson, 1997).

2 Nicholas Thomas email correspondence, October 2023.

13 | Winter 2023

Figure 1. Maker once known (Niue), Hiapo, 1880-1890. Handmade bark cloth, 68 x 88 inches, New Bedford Whaling Museum, 00.200.452.

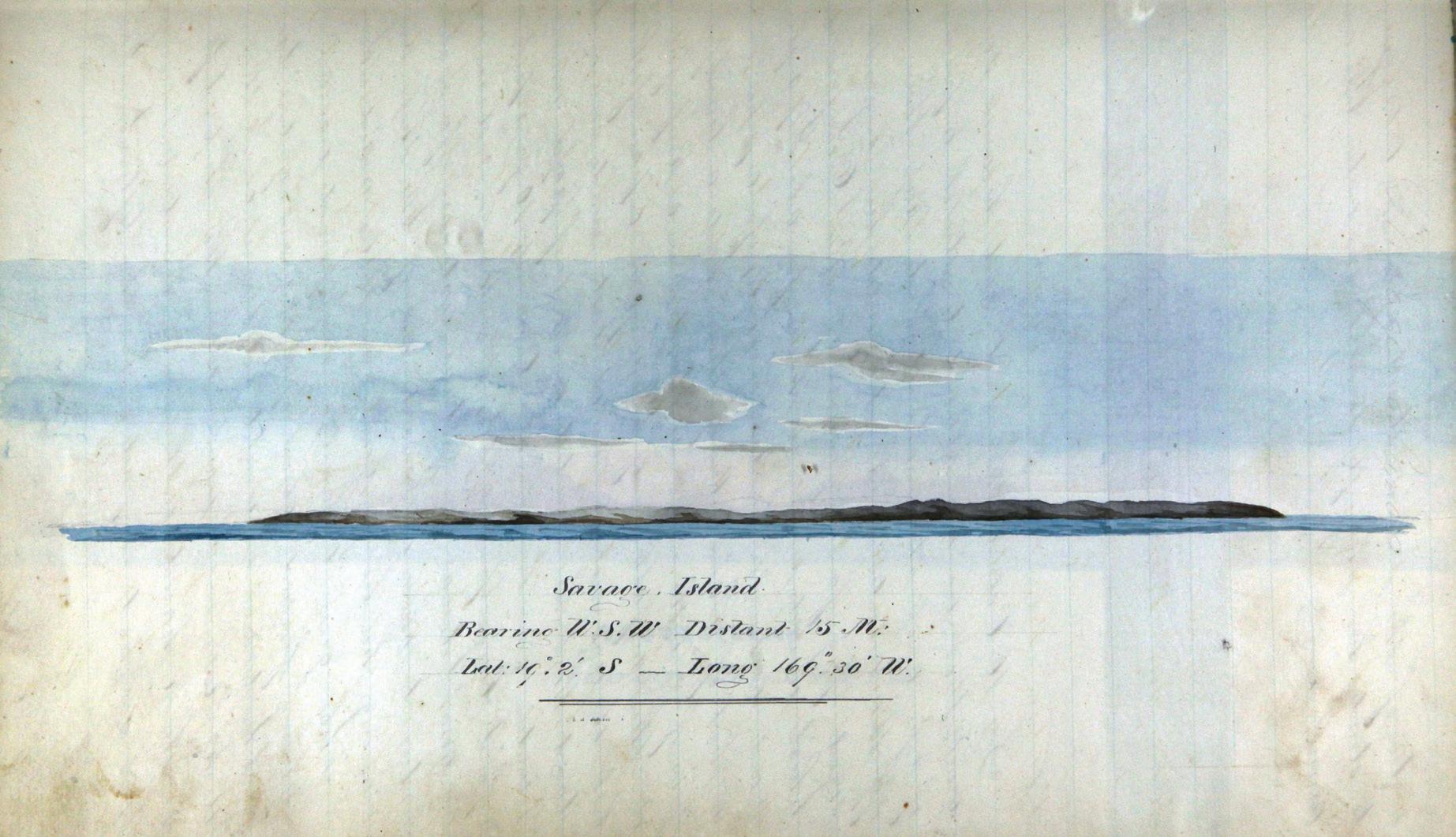

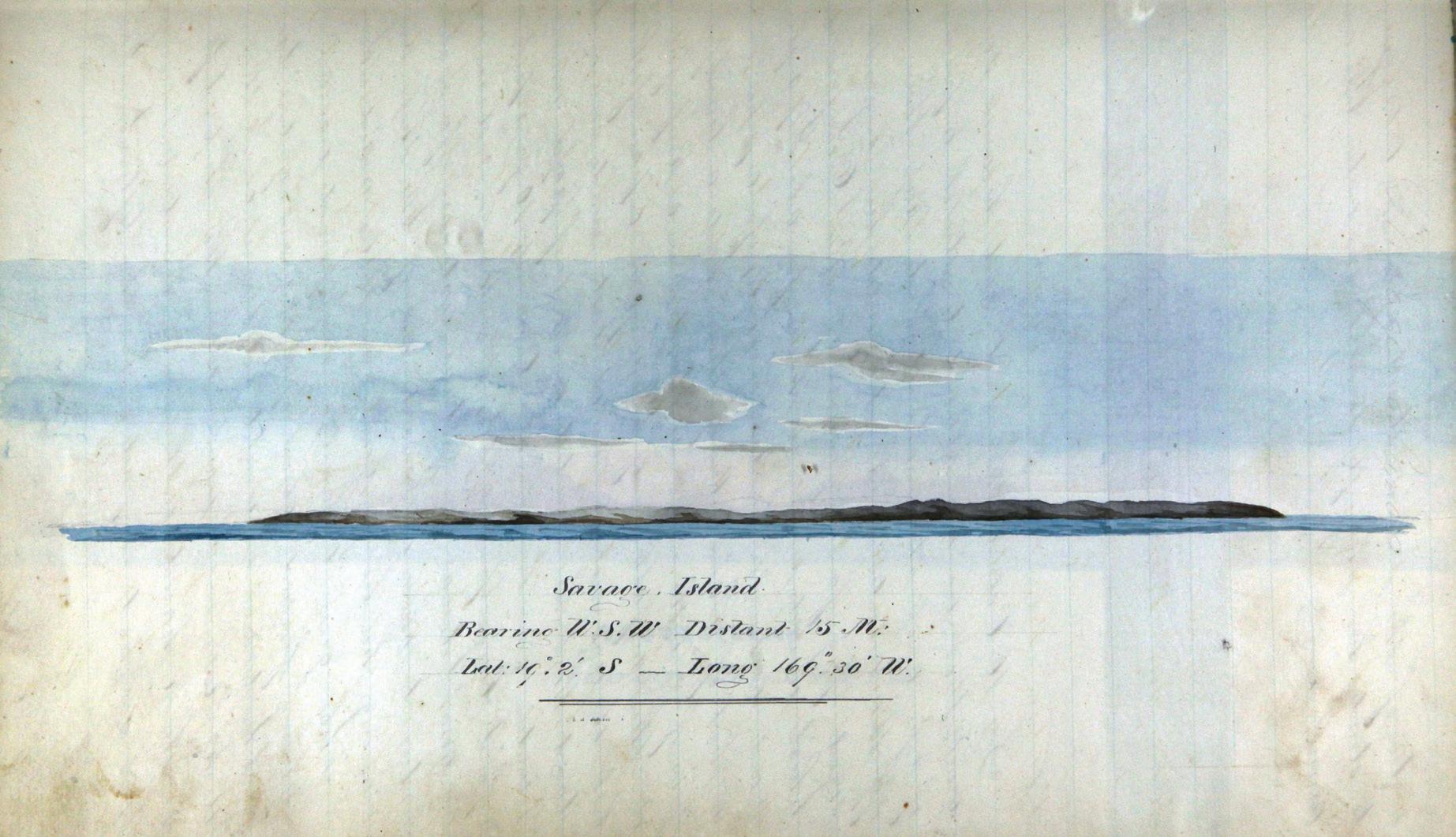

between Tonga, Samoa, and the Cook Islands and was once known as “Savage Island,” as a result of a 1774 acrimonious encounter between local people and Captain James Cook (1728-1779), during his second voyage to the Pacific onboard the HMS Resolution, 1772-1775.3 It is now called “the Rock of Polynesia,” being the largest coral atoll in the world. Niueans themselves, through their own oral tradition and histories, called their home island Niue Fekai, among other names.4

While little is known about bark cloth in Niuean culture before contact with the West, most historians credit the popularization and spread of decorated barkcloth with the arrival of Samoan missionaries in Niue in the 1830s. Samoan members of the London Missionary Society brought decorated

3 For reference, see: Margaret Pointer, Niue: 1774-1974, 200 years of contact and change (Dunedin: Otago University Press, 2015).

4 The origins of the name Niue-Fekai vary or remain undefined in different writings, translated oral stories, and accounts by visitors and Niueans alike. For reference see: Pulekula, “Appendix: The Traditions of Niue-Fekai: Ko e Tohi He Tau Tala i Niue-Fekai” in The Journal of the Polynesian Society, vol. 12, no. 1 (March 1903): 21-31; Terry Magaoa Chapman et al, Niue: A History of the Island (Fiji: University of the South Pacific, Suva, 1982); Basil C. Thomson, Savage Island: an account of a sojourn in Niué and Tonga (London: John Murray, 1902); Stephenson Percy, Niue-fekai (or Savage) Island and its people (Wellington: Whitcombe & Tombs, 1903).

barkcloth called siapo with them to Niue. They also introduced a poncho-like garment made from hiapo called a tiputa, as a form of clothing and important in the Christian conversion of the Pacific Island communities.5 The earliest extant examples of hiapo were collected by missionaries in the latter half of the 1800s. Due to this early Samoan exchange there are similarities between Samoan siapo and Niuean hiapo. Niueans decorated their hiapo with freehand painting that is similar to the Samoan style. While similar, hiapo is still distinctive in its detailed patterns that include repeating abstract and geometric designs and imagery of plants, seeds, creatures, people, and trees. The designs are often in a grid form or in concentric circles. The meaning of each hiapo belong to the maker or family that made them.

This particular hiapo includes illustrations of local identifiable plants, seeds, and patterns. Interestingly, the hiapo also includes a rendering of a Western European or American square rigged sailing ship and what appears to be people climbing rigging

5 John Pule and Nicholas Thomas, Hiapo: Past and Present in Niuean Barkcloth (Dunedin: University of Otago Press, 2005). See also: Saufa Akeli and Shane Pasene, Exploring ‘the Rock’: Material culture from Niue Island in Te Papa’s Pacific Cultures Collection, Tuhinga 22, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewas, 2011.

14

Figure 2. From A Journal of the Lucy Ann Voyage 1841-1844 by John F. Martin, edited by Kenneth R. Martin, 2016.

on the ship. Around the ship are biological forms that may be crayfish and other similar creatures that live in tide pools around the edges of the island.6 This exceptional design is interspersed with the more traditional geometric and botanical motifs commonly seen on hiapo.

This design speaks to the cultural exchanges and relationships that developed between Niue, other Indigenous communities in Oceania, and the West. By the late 1800s, mariners, missionaries, and merchants had developed trade and shipping routes in the islands, selling and buying wares, hunting, and expanding the Christian church. The impact of the London Missionary Society was evident in the churches, clothing, and in how the communities on the island were organized. The 2005 publication Hiapo: Past and Present in Niuean Barkcloth, by John Pule and Nicholas Thomas, documents three other examples of hiapos with ship imagery. These cloths, in the Australian Museum and private collections, respectively, show smaller examples of different types of seafaring vessels.7

6 Email correspondence with artist Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss and author and historian Nicolas Thomas (October 2023).

7 While the hiapo documented in the Pule and Thomas publication are not available online, a handful of other examples are available to view at: https://www.tepapa.govt.nz/ and https://www.awm.gov.au/.

While the ship may represent a vessel involved in one of the foundational encounters with Western and European explorers, mariners, or missions, i.e. James Cook aboard the HMS Resolution or John Williams (1796-1839) and the London Missionary Society aboard the Messenger of Peace, we do not know for certain. What we do know is that this hiapo illustrated the changing world in Niue and is a recognition of the unfamiliar Western and European travelers and missionaries interacting with Niue. It is a tremendous example of an Indigenous perspective of the West and is a historic document of sorts, illustrating life in Niue.

The similarity in style to other hiapo hints at a common maker, though the names of specific women hiapo makers from this time period have not been identified. While other hiapo include names of plants, places, and families, the letters and names in unique script on this cloth are, as of yet, unidentified.

The creation of hiapo in Niue decreased dramatically by 1900 with the introduction of cotton and other manufactured textiles from Europe. While the tapa tradition gained in popularity among Indigenous communities in Oceania throughout the 1900s, it is only in the past few decades that some contemporary Niuean practitioners have begun making hiapo again.

15 | Winter 2023

Figure 3. Maker once known (Niue), Hiapo detail, 1880-1890. Handmade bark cloth, 68 x 88 inches, New Bedford Whaling Museum, 00.200.452.

Figure 4. Maker once known (Niue), Hiapo detail with ship and sea life, 1880-1890. Handmade bark cloth, 68 x 88 inches, New Bedford Whaling Museum, 00.200.452.

Multi-disciplinary artist and curator CoraAllan Lafaiki Twiss (née Wickliffe) (b. 1986) is a contemporary practitioner of hiapo. Twiss spent years researching local plant life and motifs on a variety of hiapos in museum collections in Australia and New Zealand. She took on the laborious art form, making the bark, creating the pigments, and painting different types of cloths with motifs from hiapo made in the 1800s and designs of her own making. She found mentorship in her craft from her Niuean grandparents and tapa practitioners in Samoa. The result of her work, influenced by fellow Niuean artist and novelist John Pule (b. 1962), is not only new works and modern interpretations of hiapo but an illustrated catalog that includes plant and animal designs and motifs in hiapos as well as personal vignettes from community members and elders about those things depicted in the hiapo cloth.8

8 Dionne Christian, “How artist Cora-Allan Wickliffe is reviving the ancient Niuean art of hiapo,” Woman Magazine, February 23, 2021, https://womanmagazine.co.nz/, accessed August 2023.

Twiss offered the following meditations about the hiapo in the NBWM collection.

Many of the hiapo pieces left the island with only one remaining from that time period at the Taoga museum in Niue. Finding hiapo in different collections around the world is exciting because it is like meeting an ancestor, a family member that you have only heard of and now finally get to meet.

When I saw an image of this hiapo I was overwhelmed by the great strength it showed not only in form after all these years but in the pattern works. When I look around at the Niue landscape I am looking at one of these hiapo. The first time I visited Niue it was like looking directly at a hiapo in colour, you could see the plants, the flowers and smell the air where these pieces would have been made.

16

Figure 5. Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss, visit to Te Papa Museum collections, Auckland, New Zealand, 2019. Courtesy of Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss.

Multi-disciplinary artist and curator Cora-Allan

Lafaiki Twiss (b. 1986)

is a contemporary practitioner of hiapo.

Figure 6. Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss making hiapo in Samoa with Fa’apito, 2019. Courtesy of Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss.

Figure 6. Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss making hiapo in Samoa with Fa’apito, 2019. Courtesy of Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss.

The ship in this hiapo example reminded me of how Cook tried to land on Niue but was unsuccessful due to warriors throwing stones at his crew and they were covered in blood (red banana paint) which is why Niue was named Savage Island. This interaction of people from Niue seeing a large ship would have been such a foreign experience and they acted right, they protected their land and their people during that first engagement.

The flows and forms around the ship itself are images of sea life that can be found in the many rock pools on Niue. Sea snakes, shrimps, crayfish and many different types of fish are found swimming around in the shallow and clear waters on the reef.

One of Twiss’ works and the hiapo documented in this article will be on view in the exhibition “The Wider World and Scrimshaw” opening at the New Bedford Whaling Museum in June of 2024.

While there are still many questions related to this particular hiapo, we do know that it is a tremendous example of this innovative and versatile art form and is imbued with a history and life that activates stories of Niuean culture.

18

Figure 7. Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss, Hiapo, 2019. On view at Vancouver Art Gallery, courtesy of Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss.

A Life of Courage, Integrity, and Purpose

By Samantha Santos, Interim Manager of Young Adult Programs

I’ve lived on the south coast of Massachusetts my whole life and was born right here in New Bedford. Even so, before starting work at the New Bedford Whaling Museum in 2023, I had never heard of Captain Paul Cuffe (1759-1817).

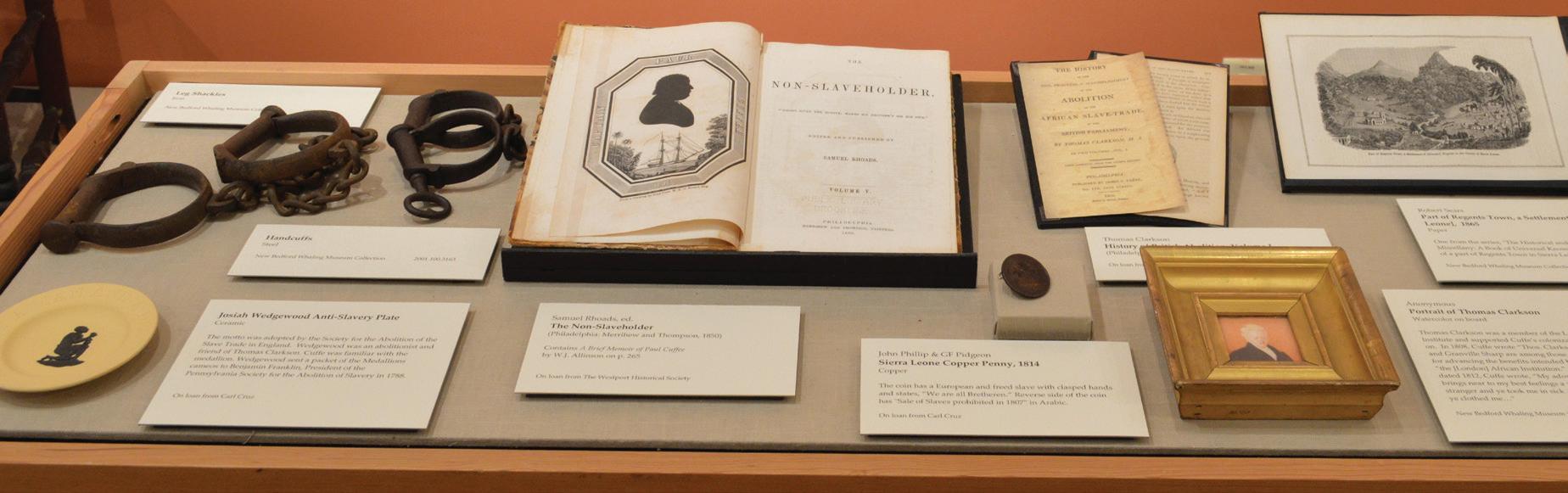

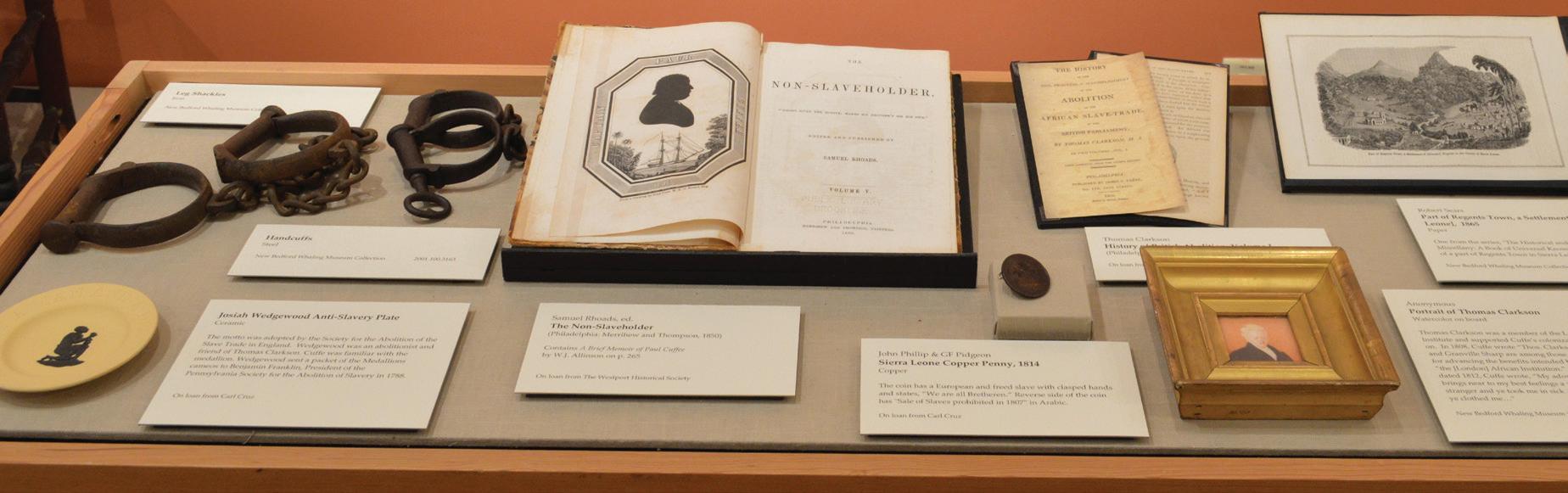

The Whaling Museum highlights this important figure in American history: a navigator, whaling master, merchant, civil rights advocate, and landowner. Curated with loans from the Westport Historical Society and Cuffe family descendants, along with objects from the Whaling Museum’s own collection, this powerful exhibition gives recognition to an often-overlooked local figure. His story is profound and one of my favorites. The exhibit is informative and moving, with interactive elements for all ages to enjoy. Of all the galleries in the Whaling Museum, I’ve found myself continuing to come back to this one, learning something new each time I walk through it.

Paul Cuffe was born on Cuttyhunk Island to a formerly enslaved father and Native American mother. He led a distinctly remarkable life. His

accomplishments include becoming one of the wealthiest African Americans of the time, a successful whaler and merchant, along with becoming one of the first African Americans to be formally accepted into the Westport Society of Friends Quaker meeting. His strong convictions are one of the things I appreciate most about Paul Cuffe. He put all possible effort into achieving what he believed in and advocated for and was by and large successful. In 1780, at 21 years old, Cuffe petitioned the Massachusetts Legislature to give African American men the right to vote, and although the petition was denied, three years later the Legislature gave all men in the state the right to vote. An outspoken anti-slavery advocate, Cuffe believed it would benefit African Americans to return to Africa and proposed the establishment of a colony in Sierra Leone, one of the first of several “Back to Africa” repatriation movements in American history. In the exhibit, you will see various objects relating to this movement. There are writings by Paul Cuffe in support of the colony and to those already settled in Sierra Leone. Additionally, there is a reproduction of the record of the families that Cuffe transported to

19 | Winter 2023

Fresh

Perspectives

Figure 1. This striking exhibit of anti-slavery memorabilia contains many objects, including shackles and a book containing a memoir of Paul Cuffe. Captain Paul Cuffe Exhibit, New Bedford Whaling Museum.

Sierra Leone in 1815. In total, 38 African Americans were brought to Sierra Leone on his ship, with the youngest passengers being just months old. I would highly recommend taking a moment to look at the names and ages of the families on the voyage. It’s likely these people were settling in a part of Africa their ancestors did not come from and they had likely never been, which further shows the racial issues of the time.

What moved me the most about his story was his meeting with President James Madison in 1812, which was a first for an African American. He sought to sit down with the President to address the seizure of his cargo ship, an incident which occurred off the coast of Rhode Island. During this historic meeting, Cuffe not only convinced the President to arrange for the return of Cuffe’s cargo, but also used the meeting as an opportunity to lobby for his proposed colony in Sierra Leone. The idea that a free man of African American and Native American descent would be welcomed to Washington D.C. by a slave-owning president truly shocked me. It is an incredibly inspiring story from a time in American history when

slavery was a major driver of the American economy and questions of racial equality were charged.

Given that there are no confirmed portraits of Paul Cuffe, likely due to the early Quaker belief that selfportraits were vain, historians and scholars only have an idea of what he may have looked like from his silhouette, the only documented likeness of Cuffe. A great set of objects on display in the gallery is a collection of photographs and possessions from Cuffe family descendants. These images of members of the Cuffe family from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries help to better envision what the influential figure might’ve looked like.

Paul Cuffe’s life was one of determination, perseverance, and activism. He never gave up on the things he set out to accomplish, and he blazed a trail for his African and Native American contemporaries. His achievements and legacy deserve our attention, and I’m certain that some part of his life will speak to you like it did to me. Next time you find yourself at the museum, take some extra time in the Paul Cuffe gallery and appreciate his unique perspective.

20

Figure 2. This exhibition shows photographs and printed materials related to Cuffe family descendants. Captain Paul Cuffe Exhibit, opened at the New Bedford Whaling Museum on September 21, 2018.

Whaling Journals as Dream Diaries

Mark

D. Procknik, Director of the Dighton Public Library, and former Librarian at the New Bedford Whaling Museum

Over the years, many prominent psychologists have offered their opinions on dreams and dream interpretation. Carl Jung believed that dreams provided a vehicle for the unconscious to communicate with the conscious mind, while Sigmund Freud similarly hypothesized that dreams provided a method for the unconscious mind to express itself in ways that were not possible while a person was awake. Whatever the clinical consensus, psychology points to dreams serving as a window into one’s unconscious thoughts. While logbooks served as the official record of a whaling voyage and provide strict reporting on notable events, journal keepers could “write anything they felt like writing and often embellished or elaborated on the daily events of the voyage.”1 As a result, journals contain detailed personal reflections on a wide range of topics, including, curiously enough, the keeper’s personal dreams, which appear in a few dozen journals.

Whaleman Marshall Keith (1838-1870), kept one

1 Michael P. Dyer, “O’er the Wide and Tractless Sea”: Original Art of the Yankee Whale Hunt (New Bedford, MA: Old Dartmouth Historical Society/New Bedford Whaling Museum, 2017), 39.

such journal onboard the 1866 voyage of the ship Cape Horn Pigeon of Dartmouth, MA, which contains several references to dreams.2 Keith’s journal entries paint a detailed picture of his unconscious thoughts and desires. He writes in multiple entries that he’s dreaming of his wife Sarah, with the majority of such entries including only a sentence or two describing his homesickness.3 However, some entries contain more detailed descriptions of his dreams, including one written on September 16, 1866, where he describes entering a room, meeting a female stranger, and dancing with her until his beloved wife Sarah enters the room. Keith immediately embraces his wife and proceeds to dance with her, writing that the “door opened and in [Sarah] came when I caught [her] in [my] arms and kissed [her] and began to dance with [her]” until the dream ended.

2 Bark Cape Horn Pigeon of Dartmouth, MA, Charles H. Robbins, master, Marshall Keith, keeper, June 29, 1866-September 4, 1867, incomplete sperm and right whaling voyage to the Indian Ocean. ODHS #371.

3 Marshall Keith and Sarah Pope (1842-1872) of Mattapoisett, MA were newlyweds in 1866, the year he left on this three-year voyage.

21 | Winter 2023

Book Talk

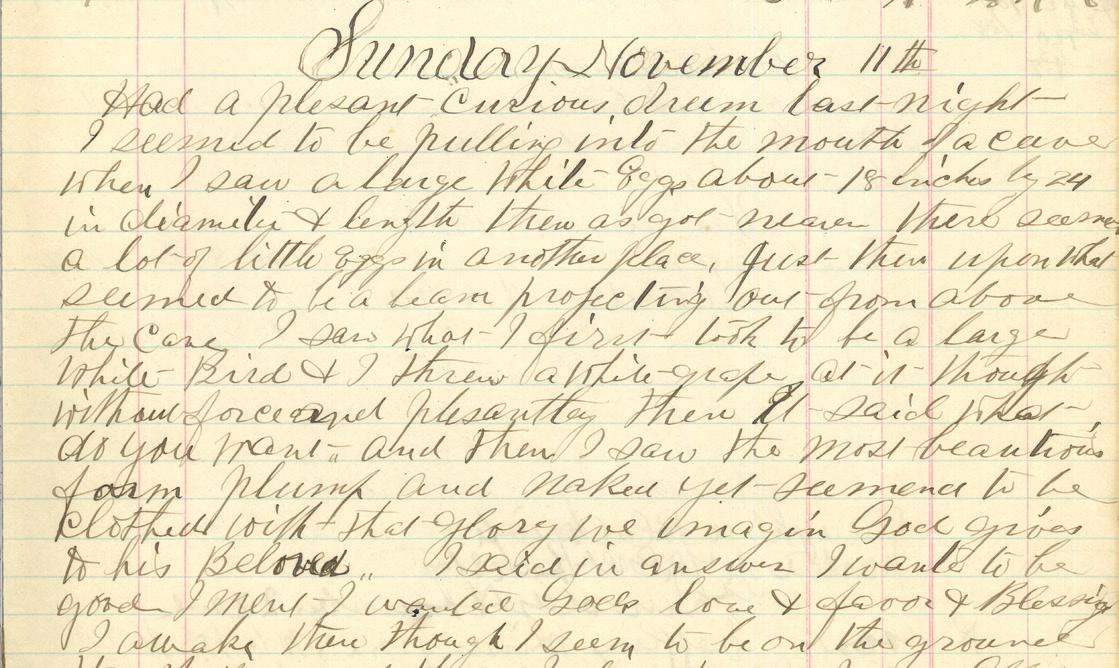

Figure 1. Andrew J. Mosher. Journal kept onboard the bark Wave of New Bedford, 18871889, a partial sperm whaling voyage to the South Atlantic, condemned at St. Helena. NBW # 1326. Gift of Levi E. Wood.

Keith offers no interpretation of this dream, electing instead to describe the events exactly as he remembers them, but it is obvious that his wife serves as the dream’s emotional focal point. Throughout his journal, he leaves little to the imagination regarding the subject of his affections, as he pens each entry as a letter to his wife back home, who dominates his waking thoughts. Some further interpretative analysis on his part might have been fascinating in this case, as there are many unanswered questions regarding his dream’s elements. Who was the stranger, why did he dance with her, and what happened to her after his wife arrived in the room? What exactly was Keith’s unconscious trying to tell him through this dream? It may be impossible to know, as the only aspect that he appears to take from this dream is his wife’s presence.

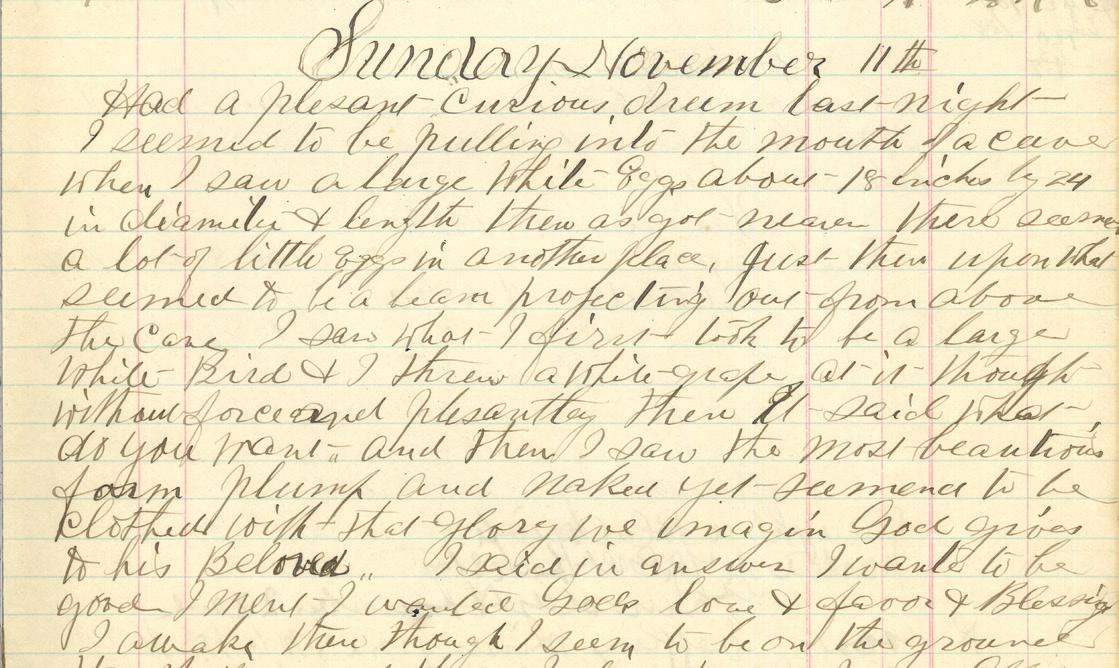

Another journal in the collection offers a much deeper glimpse into the mind of an individual. Captain Andrew J. Mosher’s journal kept onboard the bark Wave of New Bedford, 1887-1889.4 He not only describes a dream he had during the voyage, but provides his own interpretation of it. Captain Mosher writes in his journal that he had a “curious dream” on November 11, 1888, where he entered a cave and saw a large white egg. As he walked closer, he saw many smaller eggs, but a beam of light above the cave soon caught his gaze, and he witnessed a large white bird in the air. He threw a white grape at the bird and asked the bird what it wanted. At that moment, Mosher witnessed the bird transform into a form he perceived as the “glory we imagine God gives to his beloved.” Awed at the sight, Captain Mosher immediately answers his own question and states that he “wants to be good” and “wanted God’s love and favor and blessing.”

Mosher’s journal contains one of the most detailed accounts of a dream in the collection, but his interpretations are what make this journal significant. According to Mosher, he dreamt of God, who revealed to him how to be a good person and live his life. This explanation should come as no surprise to any who have read further into Mosher’s journal, as he readily displays his religious attitudes and mindset

4 Bark Wave of New Bedford, Andrew J. Mosher, master and keeper, August 25, 1887-January 5, 1889, a complete sperm whaling voyage to the South Atlantic. NBW #1326.

in multiple entries, thanking God for blessing his voyage with sperm whales, thanking God for granting the voyage with oil after stowing down, and asking God for strength and guidance in dealing with a difficult crew. It seems no coincidence that such a deeply religious person would have such a religiously charged dream.

However, given all that Captain Mosher describes in his dream, some interpretive questions remain. What was the significance of the cave, the egg, the beam of light, the grape, and the bird? Are these all religious symbols with spiritual undertones, or did Mosher’s dream have any secular messages that his interpretation overlooked? He also does not provide any detail regarding the perceived form that he interpreted as the glory of God. Could this form, perhaps, have other significance? Given his devout mindset, it may have made sense for him to see God in his dream as his conscious mind sees God’s influence everywhere in the world. However, would an individual with a more secular mindset interpret the dream the same way?

While experts continue to theorize the meaning of dreams, the dreamer’s conscious mind might not always understand what the unconscious mind is trying to convey. Were there perhaps other meanings behind Marshall Keith’s or Captain Mosher’s dreams? There is no way to tell as only they know the intensely personal details of their dreams. Keith does not describe the female stranger in any detail. She is only somebody he danced with before his wife arrived, and once his wife appeared in the room, she then became his emotional focus and the primary subject of the dream. Perhaps Captain Mosher, given his religious predispositions, would have interpreted Keith’s stranger as an angel or an angelic being, while Keith may have interpreted the unknown form that appeared to Captain Mosher as his beloved wife Sarah. Without intimate knowledge of Keith’s and Mosher’s unconscious thoughts, a detailed analysis of their dreams is impossible. However, their journals offer a unique window into their minds, as their thoughts and experiences remain preserved in the Museum’s logbook and journal collection.

22

Spreading the Word

From the Page: Transcription Stories

Naomi Slipp, Crocker Endowed Chair for Chief Curator & Director of Museum Learning

The Museum houses a staggering array of rare books, manuscripts, and archival collections, estimated at about 800,000 individual items and including over 2,500 whaling logbooks and journals.

As an institution dedicated to the promotion of scholarly inquiry, we have begun to consider how the standardized keywords and cataloguing terminology that we employ may not have caught up with the research interests of today. Indeed, what terms related to objects or manuscripts in our collection should we be including in indexes to help scholars find relevant materials and answer certain historical questions?

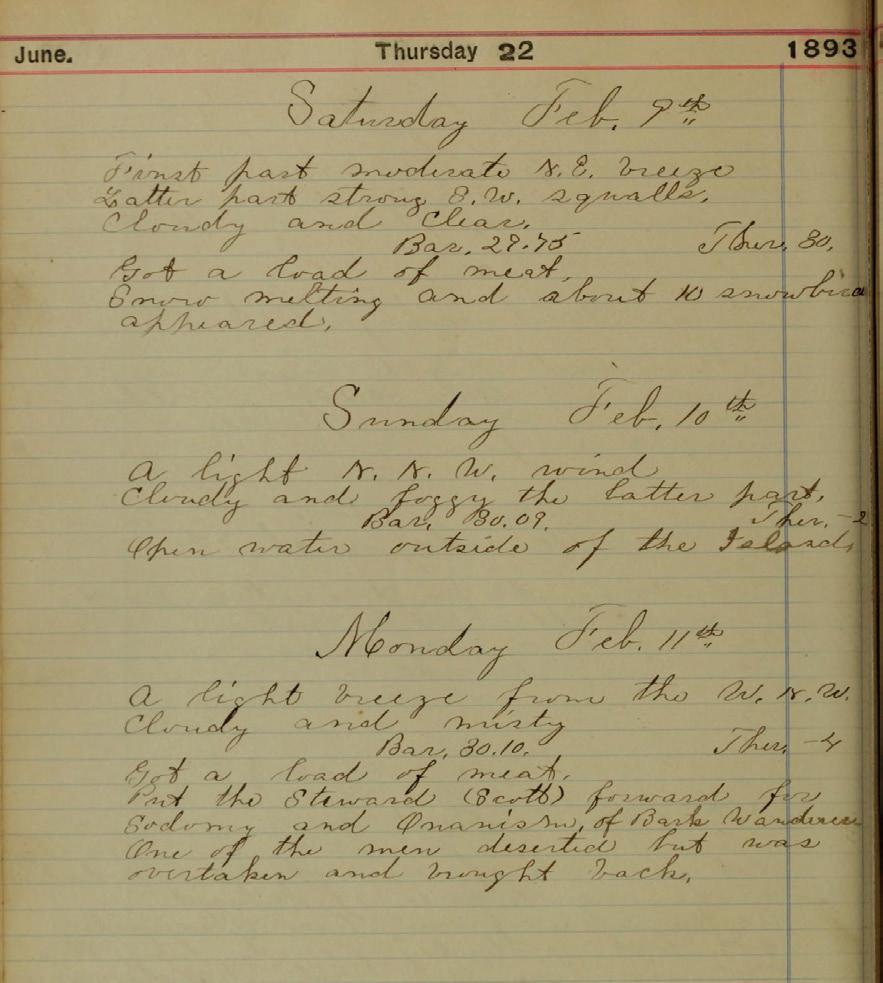

Over the past five years, the Museum has taken measurable strides in recording women’s history related to whaling and to documenting the diversity of the whaling industry. However, when it comes to the queer histories of whaling, we have work to do. This conversation began when Joe Quigley, a volunteer transcriber, shared that they had discovered reference to sodomy and onanism (self-pleasure) in one of our whaling logbooks.

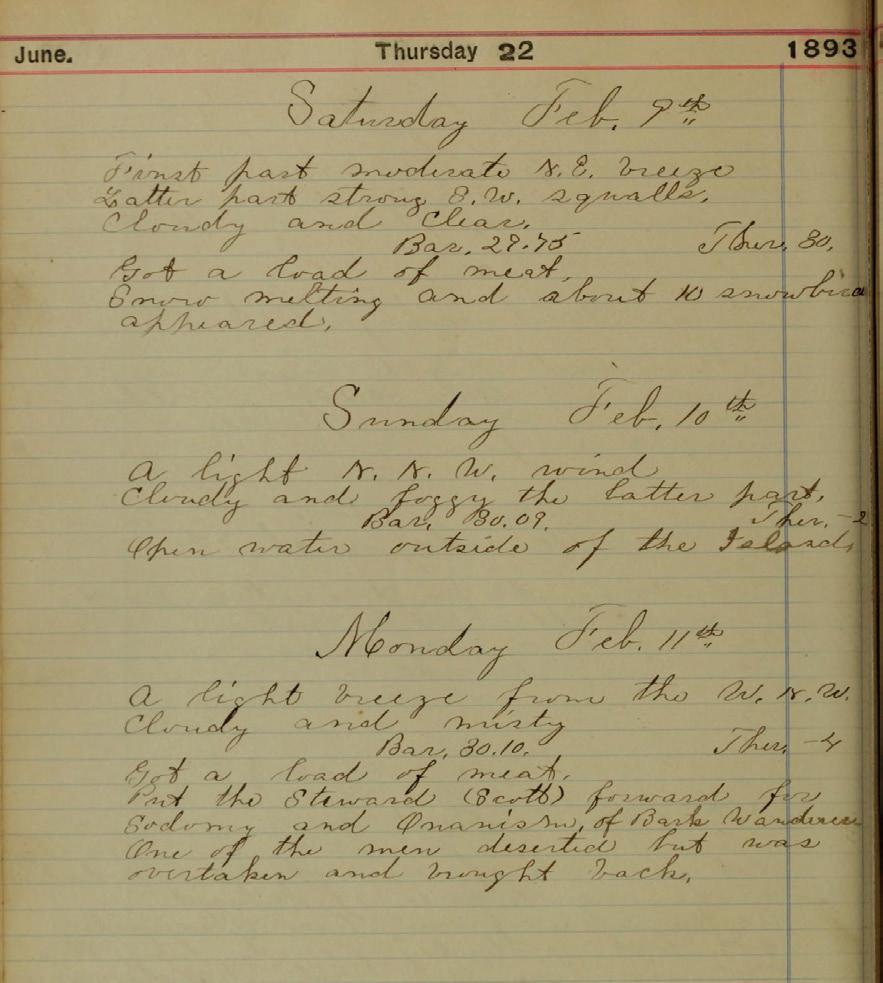

From the log of the Newport (Steam barkentine), of San Francisco, California, mastered (in the following order) by William P. Porter, James Tilton, Hartson H. Bodfish, and G.B. Levitt, kept by Hartson H. Bodfish, on a whaling voyage from 1 June 1892 to 26 September 1898:

Monday Feb 11th (1895)

A light breeze from the W.N.W. / Cloudy and misty / Bar. 30.10. Ther. -4 Got a load of meat.

Put the Steward (Scott) forward for Sodomy and Onanism, of Bark Wanderer.

One of the men deserted but was / overtaken and brought back.

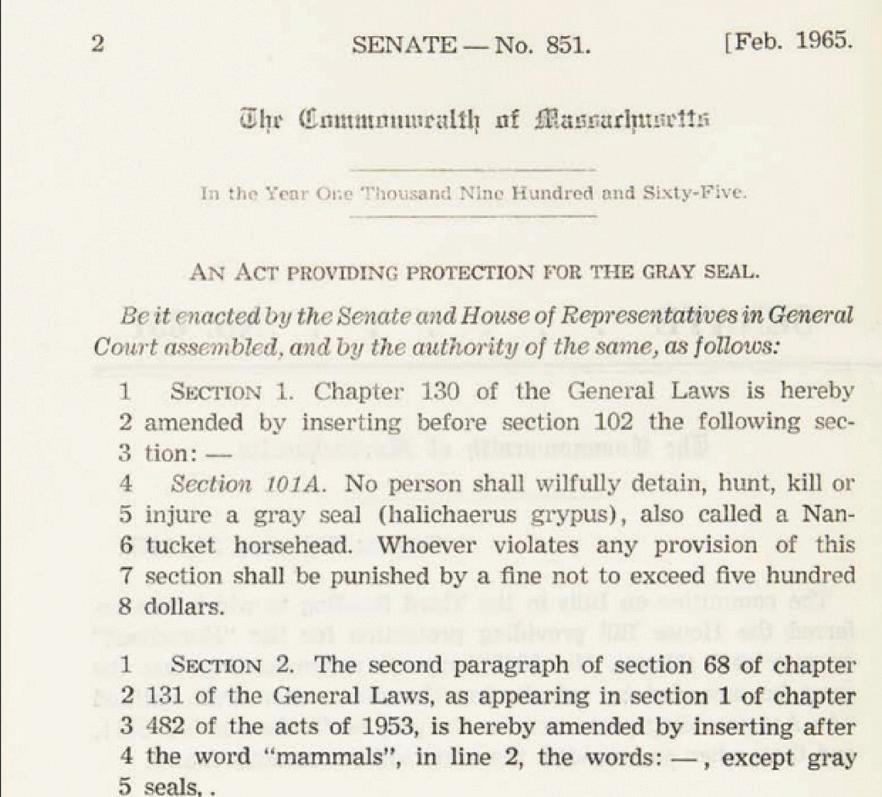

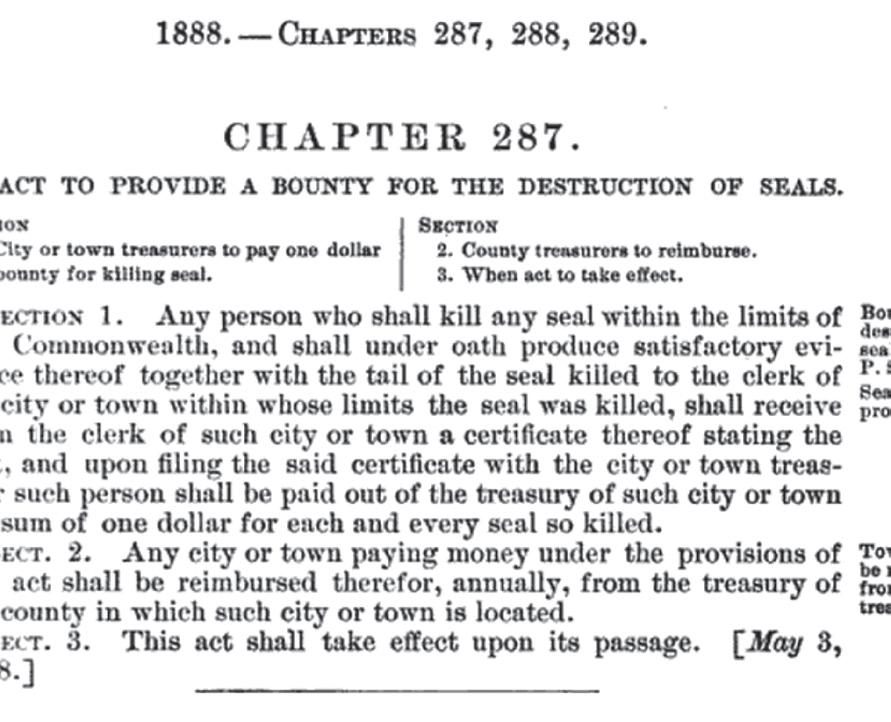

In this brief entry (Fig. 1), the keeper records that a formal charge was made against the steward of the Bark Wanderer for sodomy and onanism, both charges that, at the time, would have implied sexual acts between men. What are we to make of this?

Intimacy and romantic love between men on shipboard is implied in sources ranging from Moby Dick to the many historical studies on this topic

23 | Winter 2023

Figure 1. Entry of log of the Newport (Steam barkentine) for February 11, 1895.

related to piracy and the Royal Navy, respectively.1 The average whaling voyage lasted between 3 to 5 years. On these voyages, an average of 20 men were closely confined at sea.

Despite this, few historical records related to whaling history document instances of romantic love or sexual acts between men on shipboard or at port (Fig. 2). In most cases, when these stories are recorded, it is for disciplinary or legal purposes and framed as illegal or amoral. This raises a number of questions:

1) did period censorship of personal journals or historical sources intentionally erase such histories?

2) did captains overlook such activities to keep the peace, or avoid the headache of a formal charge?

3) could individuals reasonably hide such relationships at sea and avoid being caught?

1 For further reading, see: Cecil Adams, “Rum, sodomy, and the lash,” The Straight Dope (Sept 2, 2008); B. R. Burg, Sodomy and the Pirate Tradition (New York: New York University Press, 1995); Briton Cooper Busch, “Whaling will never do for me”: The American Whaleman in the Nineteenth Century (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2009); Kyle Dalton, “Homosexuality in the Royal Navy,” British Tars, 1740-1790 (January 15, 2018); Arthur N. Gilbert, “Buggery and the British Navy, 1700-1861,” Journal of Social History 10:1 (1976), 72–98; Shane McMurray, “Sailors and sexuality: searching for LGBTQ+ histories in the Royal Navy,” Royal Museums Greenwich (Feb 1, 2023); Suzanne J. Stark, Female Tars: Women Aboard Ship in the Age of Sail (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2017).

4) did such relationships go unrecorded out of prurience or a reluctance to name the act? 5) how common were tender, loving consensual relationships between whalers?

We may never know how Scott self-identified, the context of this charge, who he had a relationship with, or what happened to them after this event. The logbook makes no other references to Scott.

We can, however, think about sexuality in whaling history, and consider what tools we, as an institution, are providing to researchers who are interested in studying this topic in relation to our collections. Moving forward, we will be surveying the subject tags that we use to identify the contents of our manuscript collections to be as broadly inclusive as possible. Finding references to individuals like Scott in the historical record point to potential maritime histories that have yet to be fully explored or told.

Curious what other collections-based maritime histories relate to gender and sexuality on shipboard? Visit the Museum’s newest temporary installation, curated by Photography Collection Curatorial Fellow Marina Wells (PhD candidate, American & New England Studies, Boston University), to learn more about this topic.

24

Figure 2. O’Neil Studio, New Bedford, Mass., “Portrait of two unidentified young men,” c. 1880. Carte-de-visite, NBWM 2009.6.19.

Exhibit Preview

The Wider World & Scrimshaw

In June 2024, the New Bedford Whaling Museum will open the major exhibition The Wider World & Scrimshaw, which takes the Museum’s scrimshaw collection (objects carved by whalers on the byproducts of marine mammals) and places it in conversation with carved decorative arts and material culture made by Indigenous community

members from across the Pacific Rim and Arctic. Native communities across Oceania, the Pacific, and Arctic had cosmologies related to whales, distinctive maritime traditions involving marine mammals, and vibrant carving styles. They were also impacted by commercial whaling ventures, and the external pressures from colonialism and Western exploration.

25 | Winter 2023

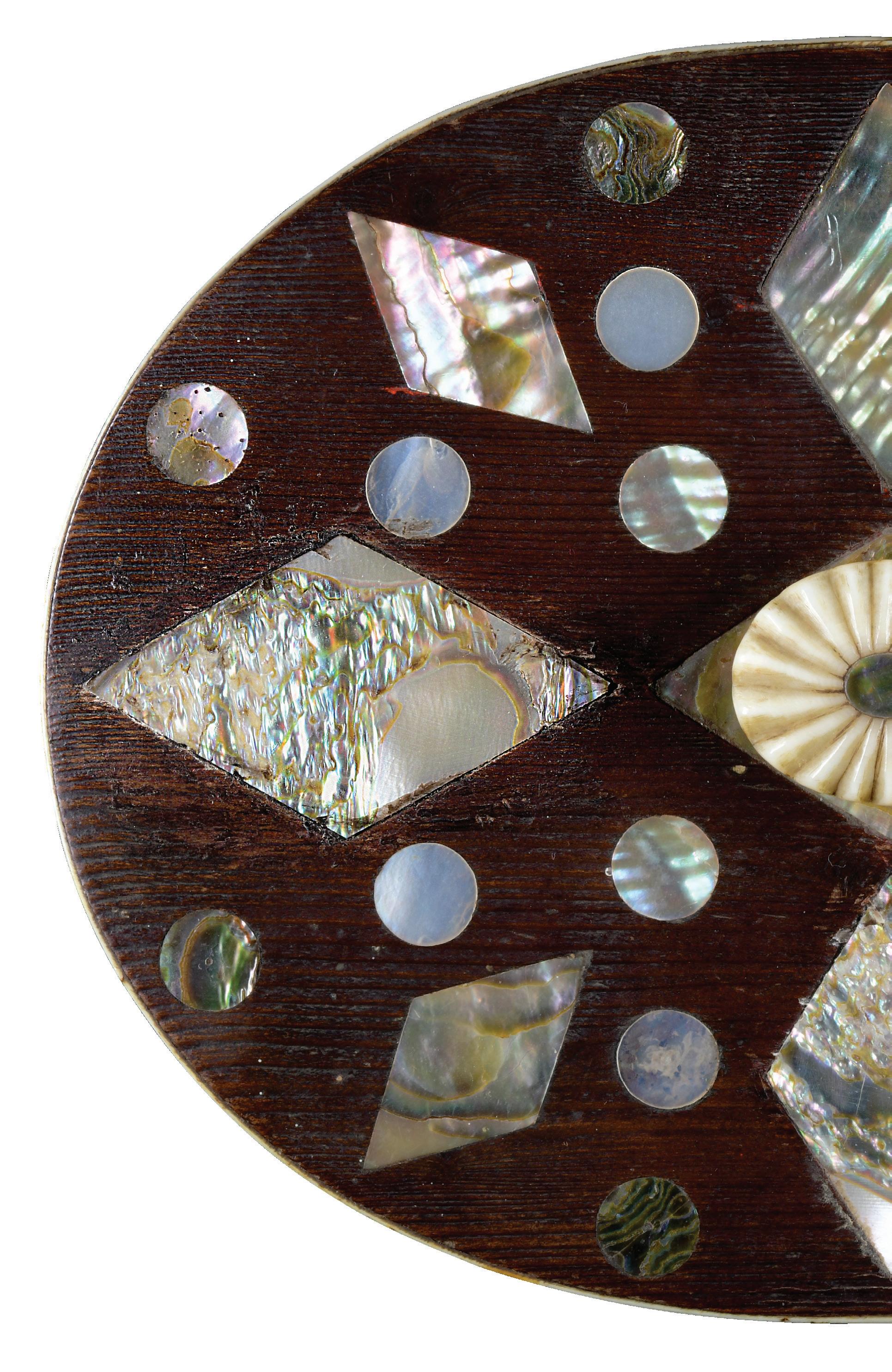

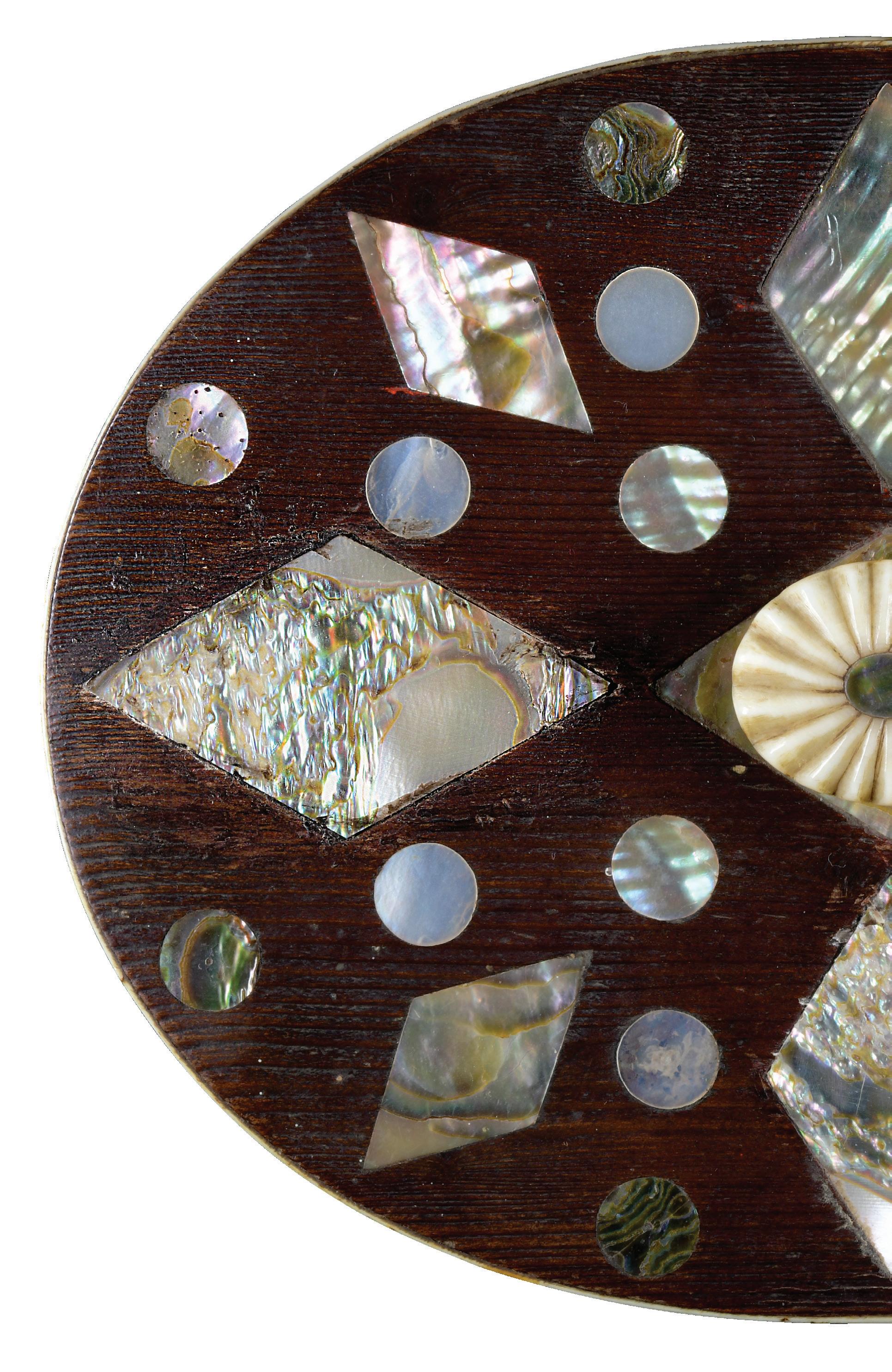

Maker once known, Scrimshaw box, c. 1860. Red cedar, whale skeletal bone, green abalone, and mother of pearl, 7 x 53/8 inches, NBWM, 2001.100.1087

This interdisciplinary, community-driven, and collections-focused project engages questions about identity, place, and material, and considers how exploration and whaling impacted the production of material culture in this diverse region between 1700 and today. The exhibition showcases over 300 objects, paying particular attention to ones that indicate cultural and material exchanges. How did Pacific Rim communities encounter whalers and influence items produced, and how did whaling (internal or external) impact these communities and their unique art forms?

Open-ended questions probe visitor expectations about different cultural products from Oceanic material culture and Arctic carvings to engraved sperm whale teeth, and explore issues related to trade, markets, taste, and patterns of popular consumption; assumptions about materials (coconut shells, whale teeth, walrus ivory, human hair), their circulation, and animal agency; differences between cultural and commercial value systems; disciplinary hierarchies related to craft traditions, folk-art, anthropology, and “fine” art; and gender roles, for making and consumption.

This oval scrimshaw ditty box demonstrates the dynamic circulation of Indigenous Pacific materials utilized by whalers to make and decorate scrimshaw while on shipboard whaling in the Pacific. The body of the box is made of whale skeletal bone elaborately engraved with a repeating geometric hatching pattern, inset with a leafy sprig or feather. The lid of the box (see centerfold) is made of western red cedar wood (Thuja plicata) inlaid with diamonds and dots shaped from richly iridescent green abalone shell (Haliotis fulgens) and paler iridescent dots made of nacre (mother of pearl) from the nautilus shell (Nautilidae). The materials used to make this box are consistent with the geographical regions along the coast of California, Oregon, and Kodiak Island, where gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus) were commercially exploited in the 1850s through 1870s. How did the whaler who made this box acquire these geographically specific materials? Who did they meet when trading, and what forms of cultural expression informed the design, style, and construction of this box?

These questions are just some of the rich considerations that come to the fore in Wider World. We are working with a diverse advisory board to explore the rich cultural traditions, carving forms, and material exchanges that emerged and were shaped by cultural contact across the Pacific Rim in this period.

The Wider World & Scrimshaw is open June 14 to November 11, 2024 at the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

Native communities across Oceania, the Pacific, and Arctic had cosmologies related to whales, distinctive maritime traditions involving marine mammals, and vibrant carving styles.

26

27

28

From Our Fellows

The Daguerreotype and Ambrotype in New Bedford

Marina Dawn Wells, Photography Collection Curatorial Fellow

The New Bedford Whaling Museum/ Old Dartmouth Historical Society holds somewhere around one million pieces in its collection; tens of thousands of three-dimensional objects including ship models, scrimshaw, natural history specimens, tools, dolls, textiles, prints and paintings, maps and charts, ships plans, books of all kinds, and ream upon ream of manuscript material. However, about 200,000 items comprise an important but lesser-known area of the collection: photography. Since September of 2022, I have worked as the

Photography Collection Curatorial Fellow, where I have studied, catalogued, and generally gained a broad understanding of this unique segment of the Museum’s collection. My primary focus has been to survey and assess the earliest works in this group, comprising tens of thousands of images made before 1900 and representing the output of hundreds of photographers.

At the second annual meeting of the Old Dartmouth Historical Society in 1905, members agreed to

29 | Winter 2023

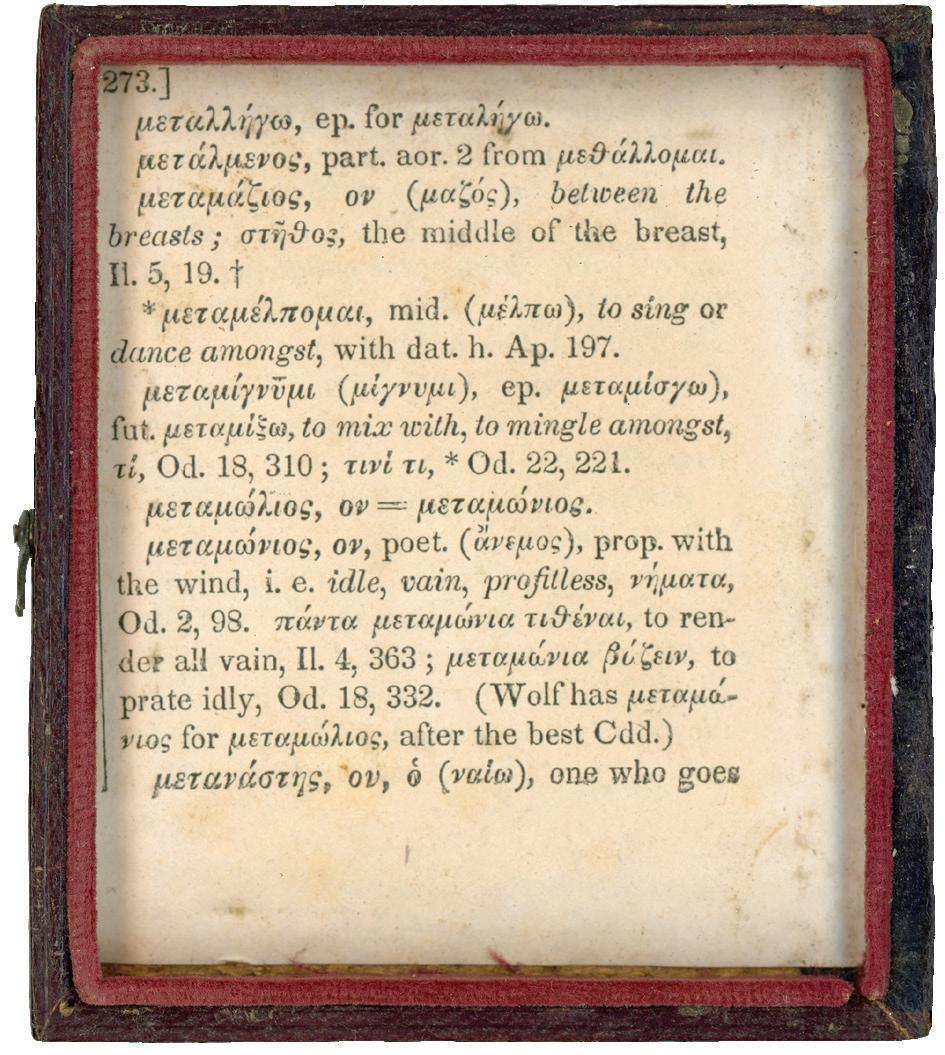

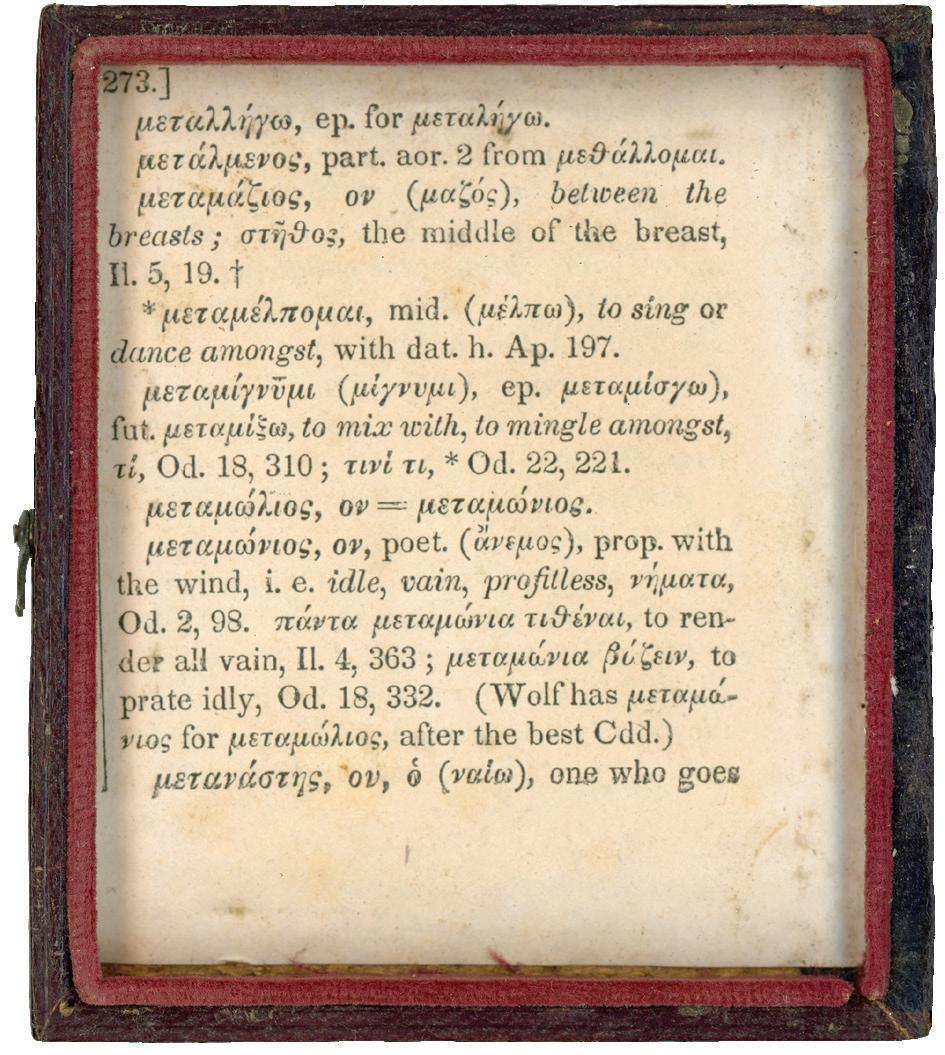

Figure 1. Maker once known, Portrait of Thomas Almy and the excerpt from a Greek-English dictionary that hid behind it, undated. Sixth plate daguerreotype, NBWM 2018.23.54.

Almy was a Rhode Island-born seaman who became a master’s mate on the U.S. Navy steam-sloop USS Wachusett. Almy died during the Civil War in battle at City Point, Virginia in 1862. The corner of the dictionary’s page lists such Greek translations as “between the breasts,” “to sing or dance amongst,” “to mix with, to mingle amongst,” and “idle, vain, profitless.”

This cased ambrotype was likely taken at the same time as Captain McKenzie’s portrait in the collection (2000.100.1830), either before his departure as first mate on the whaling bark Mars (1856-60) or as captain of the whaling bark Cherokee (1860-64). It is possible the McKenzies exchanged portraits before the captain’s time at sea. Looking closely at the edges of the brass mat, it is possible to discern a parallel mat behind the one pictured. This example is reversible and shows the extent to which ambrotypes were transparent. Because an ambrotype was actually a negative image, it required a black backing to make the negative image appear to be a positive one.

allocate funds and space to support the collecting and exhibition of photography.1 Over a century later, the collection now spans nineteenth-century tintypes to present day digital photographs. Within this diverse array of photographs are hundreds of daguerreotypes and ambrotypes, some of the very first types of photographs invented. Daguerreotypes were introduced to the United States from France in

1839, and glass ambrotypes followed in the 1850s.2

Both excited the American public and emerged as accessible forms of portraiture for people voyaging in and out of New Bedford’s bustling whaling port at

1 “Proceedings of the Second Annual Meeting of the Old Dartmouth Historical Society at the Rooms of the Society, New Bedford,” Old Dartmouth Historical Sketches 9 (March 17, 1905), 4.

2 Historians of photography generally credit Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (1787-1851) and William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) with the two first photographic inventions that occurred about simultaneously in 1839. Daguerre created silvered copper plates called daguerreotypes, and Talbot created salt prints called calotypes or talbotypes. Daguerre’s invention became more widespread in its commercial accessibility, in standardized sizes and cases that the ambrotype would later adopt. James Ambrose Cutting (1814-1867) patented the ambrotype in Boston in 1854, although it had already been in use after Frederick Scott Archer (1813-1857) published in England about the wet collodion process in 1851. As is evident from the daguerreotype and talbotype, these figures often gave eponymous names to their inventions—and it is said that ambrotype may have come from Cutting’s middle name, derived from the Greek for “immortal.” See, for example, Mary Warner Marien, Photography: A Cultural History (London: Lawrence King, 2010 [2002]).

30

Figure 2. Edward Sidney Dunshee, Portrait of Susan A. McKenzie, wife of Scottish-born whaling captain James H. McKenzie, undated. Sixth-plate ambrotype, NBWM 2000.100.1831.

An advertisement behind the plate, glass, and brass preserver reads, “Made by William Shew, corner of Court & Howard Sts, Boston.” Shew was a case maker, daguerreotypist, and dealer of daguerreotype materials from 1844 to 1850.

midcentury. Examining roughly 500 of these studio portraits in the NBWM collection has helped piece together a clearer picture of how photography first developed in nineteenth-century New Bedford.

In the 1840s and 1850s, photography was a combination of artistry and chemistry. Daguerreotypists captured light on polished copper plates that they protected in folding cases, with paper lining on one side of their metal surface, and a pane of glass and brass mat on the other. In 1841, itinerant photographers “Messrs. O’Brien and Faxon” were the first to create these material composites in New

Bedford.3 They would have arrived on those cobbled streets with various materials in tow: silvered copper plates that would capture the images, chemicals like

3 According to the New Bedford Mercury on July 9, 1841, O’Brien and C. Faxon performed their work at number 7 Cheapside, now Purchase Street. They advertised taking on potential pupils for the few days they would be in New Bedford, and remarked that they copied the practice of “Professor Morris of New York.” They would also travel to Springfield, Massachusetts, to set up a studio at Masonic Hall the following September and October, according to the Springfield Gazette. See also Nicholas Whitman, A Window Back: Photography in a Whaling Port (New Bedford, Mass.: Old Dartmouth Historical Society, 1994); Chris Steele and Roland Polito, A Directory of Massachusetts Photographers 1839-1900 (Camden, ME: Picton Press, 1993).

31 | Winter 2023

Figure 3. William Shew, Hand-colored daguerreotype of a deceased child holding a flower, 1840s. Sixth plate daguerreotype, 2000.100.1782.

iodine and mercury to sensitize and develop them, and bulky wooden cameras that honed light through their brass-mounted lenses. This chemistry served to fix images on plates of standardized sizes: sixth plates measured 2 ¾ x 3 ¼ inches, and ninth plates just 2 x 2 ½––with rarer whole plates rendered on 6 ½ x 8 ½ inch pieces of metal. To expose the sensitized silvercopper surface, customers sat in front of the camera for lengthy exposure times. Locating a studio on the upper floors of a building gave access to better light and often shortened the amount of time a sitter had to remain in one position. In the 1850s, photographers captured portraits in a similar way using an even

lower-cost process to make ambrotypes. While ambrotypes look much like their daguerreotype cousins, they are actually glass collodion negatives. Photographic workers would paint the reverse of the glass black, or line the case with black velvet to make the image positive. The earliest photographs were complex processes combining concentrated thought, material manipulation, and entrepreneurial intent.

After the complexities of mechanical and chemical development, workers in photographic studios assembled daguerreotypes and ambrotypes into presentation cases standardized for easy assembly.

32

Figure 4. Maker once known, Hillman and Osgood, dealers in crockery and glass-ware, at 143 Union Street, 1859. Quarter-plate ambrotype, NBWM 1994.24. The business is listed in the New Bedford Directory in 1859, providing the ambrotype with an approximate date.

This process involved lining the case with paper so that the plate did not directly rest upon the rough wood interior. Some studios used cases pre-lined with advertisements for either the case maker or photographer, while others used blank scrap paper or paper cut from publications. After all, there was little reason to expect a customer might look at anything beyond the portrait itself.

In one cased example at NBWM, a daguerreotype of Thomas Almy held behind it a corner of a Greek–English dictionary page. In another, lifting the portrait of a bespectacled Quaker man revealed a shard of the 1841 Edgar Allen Poe story “Never Bet the Devil Your Head.” Others sometimes hold material added after the sitter left the studio. One ambrotype of ship owner and whaling merchant Charles W. Morgan was held in a case with a perfectly preserved leaf inside. It also included a note, likely written by Morgan’s daughter to his sister: “For Sue with her Cousin Emily’s love + wishes for a happy New Year – Jan. 1st 1860.” If the gifted portrait preserved the industrialist’s likeness, the case also protected the sentimentality and materiality of the note and leaf inside it.

The Museum’s early photography collection represents a snapshot (as it were) of the materials, local photographers, and—of course—various sitters captured in the 1840s and 1850s. In contrast with artwork made with brush or pencil, these types of photographs were available for a significantly lower cost (and in significantly less time) for anyone who wanted their portrait taken. All manner of people stepped into studios for this purpose—affectionate friends and newlyweds, white folks and people of color, wealthy merchants and young mariners on the verge of shipping out. As early as 1841, sailors were a noted audience, as Philander Bryant (18031863) advertised in the New Bedford Mercury. Bryant established himself shortly after O’Brien and Faxon—perhaps one of their students, and the first photographer to settle in New Bedford—and catered to “Seamen… who are about to depart on long voyages.”4 Just as sailors gifted scrimshaw or locks of hair to their loved ones, they also offered portraits to

4 New Bedford Mercury, August 20 1841.

preserve their memory or carry another’s with them to sea. Popular ambrotypist Edward Sidney Dunshee similarly advertised about his wares in 1859, “They are a durable picture for carrying to sea, and will not change even under water. They are secured in such a manner as to be excluded from air, therefore will last ages.”5 Surely it was a selling point for sailors that ambrotypes were impervious to salt and spray, since it was the memory of their photographed loved ones that they really sought to preserve during their months or years at sea.

Meanwhile, sailors were not the only people who employed this commemorative function of these “mirrors with a memory.”6 Other examples preserve the faces of the young, the elderly, and even the deceased. Daguerreotypes in the NBWM speak to this impulse, including one hand-colored daguerreotype depicting a child, deceased, holding a flower. As art historian Anne Verplanck has argued, daguerreotypes elicited deep emotional responses due to how faithfully they conjured the likeness of loved ones, especially in their absence.7

Consumers were evidently eager to preserve individual lives via portraiture with these newly accessible photographic forms––a priority that explains some of the lack of outdoor photography in this early era. The oldest known photograph of New Bedford’s landscape is a daguerreotype thought to be by Morris Smith (1803-1886; the original is now lost and only lives on in reproductions). The Museum’s oldest original outdoor photograph of New Bedford is an ambrotype view of 143 Union Street made in about 1859, which depicts the crockery and glassware business of Roland L. Hillman and Alfred

5 Advertisement in The New Bedford Directory (New Bedford, Mass.: Charles Taber & Co., 1859).

6 Oliver Wendell Holmes used this famous phrase in “The Stereoscope and the Stereograph,” in the Atlantic Monthly, June 1859. Reprinted in On Photography, A Source Book of Photo History in Facsimile, ed. Beaumont Newhall (Watkins Glen, NY: Century House, 1956).

7 Anne Verplanck, “‘The Shadow of Your Noble Self’: The Reception and Use of Daguerreotypes,” West 86th (2017): 47-73.

33 | Winter 2023

M. Osgood.8 Outdoor views like this were not as commercially viable until after the Civil War when albumen printing expanded beyond portraiture. It was at that point that local enterprises like the Bierstadt Brothers and Stephen Fellows Adams sold albumen prints of the New Bedford cityscape, mostly as stereoviews for widespread entertainment.

In the late 1850s and early 1860s, after just two decades in New Bedford, photography shifted again. Stereoviews and other emerging photographic forms, like tintypes, glass plates, and albumen prints, made new visual technologies increasingly accessible to a broad audience. About ten daguerreotypists worked in New Bedford at some point in the 1840s. By the time the Civil War broke out over fifty artists had worked in the city—that number doubled again by 1870 to over 100 photographers. By the turn of the century, over 200 photographers had entered in and out of the town that had grown into a city, and many have left their marks scattered throughout the Whaling Museum’s collection. Given how unexplored this history has been, untold numbers of photographers, sitters, and materials are waiting to come to light.

8 The New Bedford Directory (New Bedford, Mass.: Charles Taber & Co., 1859). Meanwhile, NBWM 50105 may be the oldest outdoor photo in the collection, a daguerreotype with a case produced by a manufacturer dated between 1848 and 1850, but the image depicts a post office that does not belong to New Bedford. It is also possible the Whaling Museum boasts the oldest photographs of whaleships, 2000.100.1824 and 2008.12, taken in Hawaii around 1857. Other instances of early non-portraiture include ambrotypes of a horse drawn cart (2000.100.3359), a horse carriage on a landscape (2000.100.3757), as well as an image of Niagara Falls almost certainly by Platt D. Babbitt (00.175.15). Reproductions of early outdoor photographs of New Bedford also exist in our collection as UN.37, 1995.28.4, and in the Benjamin Baker Collection, and are resources that deserve significant future attention to understand early outdoor photography in New Bedford.

Within this diverse array of photographs are hundreds of daguerreotypes and ambrotypes, some of the very first types of photographs invented. Daguerreotypes were introduced to the United States from France in 1839, and glass ambrotypes followed in the 1850s.

34

An Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) Grant

Improves Collection Preservation and Access

Michael P. Dyer, Curator of Maritime History at Mystic Seaport Museum, and Former Curator of Maritime History at the New Bedford Whaling Museum

35 | Winter 2023

All About stuff

Fig. 1. Curatorial Assistant Emma Rocha selects a book from one of the newly installed compact storage units funded through the IMLS grant.

Acommon refrain in any discussion of increased investment in museum storage equipment and infrastructure is that such back-of-the-house projects are generally hard to fund. Poured concrete, windowless HVAC tempered spaces filled with locked doors, steel shelving, fire-proof filing cabinets, archival boxes, folders, envelopes, buffered tubes, linen tape, inert corrugated plastic, Mylar, and the other arcane accoutrements necessary to the long-term viability of collections can be a yawn. To folk like curators, collection managers, archivists, and registrars, however, such improvements are the staff of life for two simple reasons: preservation and access. Those two words are the Holy Grail. Fortunately, federally supported organizations like Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), state and community cultural councils, community foundations, and some private foundations offer competitive grant funds for worthy infrastructure projects. The question remains: to what end, exactly, are such storage improvement efforts aimed?

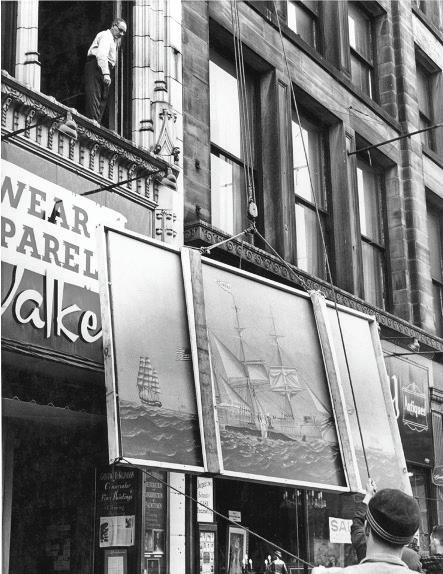

In August 2022, the Museum was awarded an $86,000.00 grant from IMLS through the Museums for America program for the design, purchase, and installation of compact shelving for the collection storage area dedicated to rare books, manuscripts, archives, reference books, special collections, and photography. The new layout would better utilize the existing space. The actual award reads as follows: