8 minute read

By Sienna Stevens

Memento Matamoe: Representing Death in Colonial Tahiti

By Sienna Stevens

2022 Summer Research and Interpretation Curatorial Fellow, New Bedford Whaling Museum

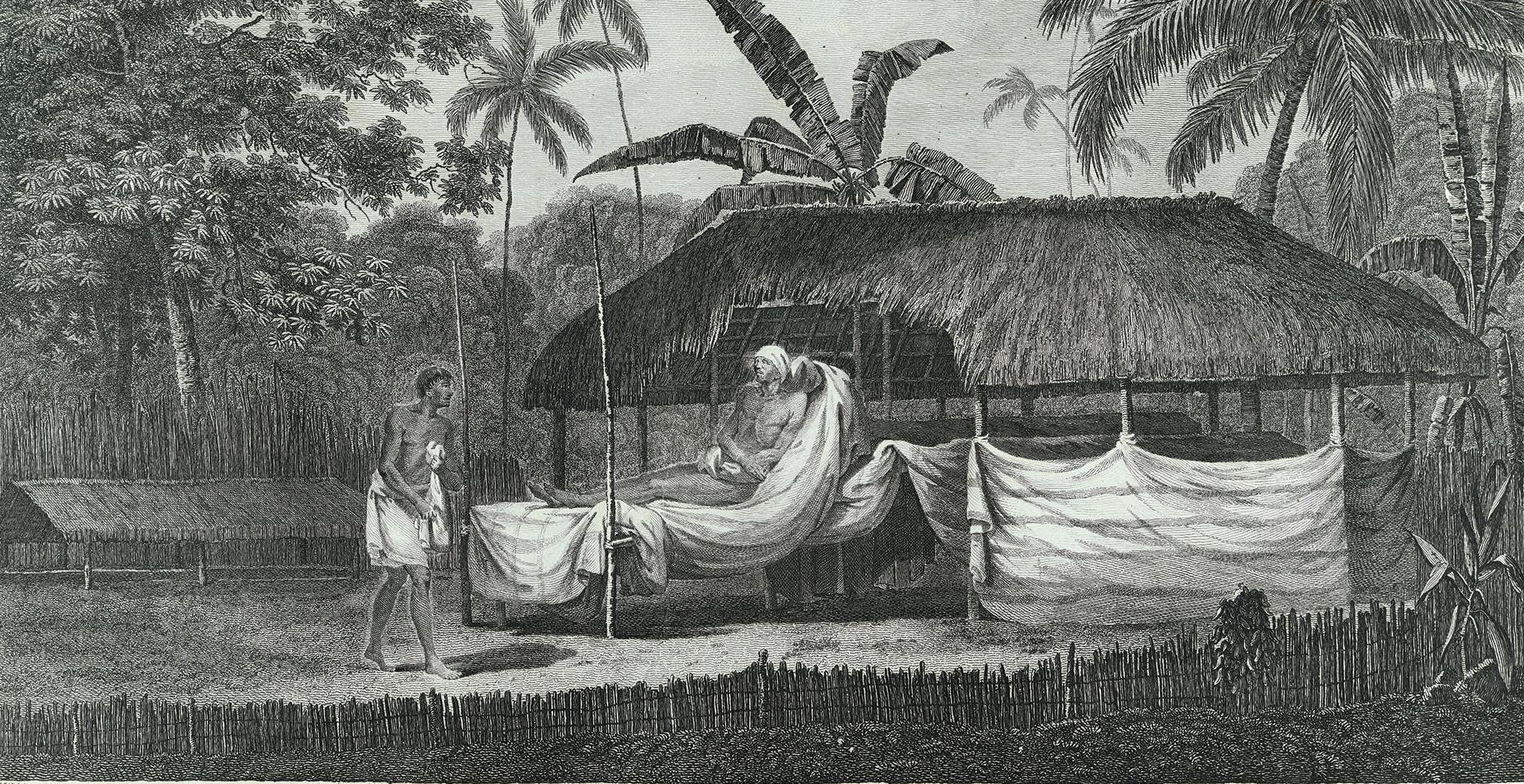

William Bryne after John Webber, “The Body of Tee, a Chief, as Preserved after Death, in Otaheite,” c. 1784, British engraving, etching and stipple on cream laid paper. NBWM, 00.131.98

As the 2022 Research and Interpretation Fellow, I have focused on evolving Western ideas of Oceania, and found, within the great diversity of the Museum’s collection of such materials and objects, pieces that provoked broader questions. One such piece is a print, an engraving, by John Webber (1751-1793), titled The Body of Tee, a Chief, as Preserved after Death, in Otaheite. Webber was the official artist of Captain James Cook’s third voyage to the Pacific and though the print is much older I immediately associated it with Paul Gauguin’s famous 1892 painting Arii Matamoe (The Royal End) held at the Getty Museum. I felt a connection emerge between these works with their parallel (and sensational) subject matter. Each image captured death in Tahiti in visual vignettes. Gauguin’s painting, created over a century after Webber’s, spoke to death and dying from the vantage point of an artist who occupied a space within the expanded French colonial influence in Tahiti, a space accompanied by a sharp shift in cultural governance. Webber’s print ostensibly served as a documentary illustration from a period of the earliest contact between Western mariners and the peoples of Oceania, long before actual colonial processes overtook the region. Comparing the two art works

offers valuable insights into how Tahitian culture, in this case funerary practices, and perhaps something more, has been perceived, not only by the audiences for the art, but by the artists themselves.

Webber’s Body of Tee emerged in 1777 from Cook’s third and final voyage (1776-1778). It documents the intricate process of preserving the bodies of deceased chiefs in 18th-century Tahiti. One seaman on the voyage wrote:

“The body [of Tee] was entire in every part; putrefaction seemed hardly to be begun: and not the least disagreeable smell proceeded from it; though this is one of the hottest climates, and Tee had been dead above four months…On enquiry [sic] into the method of thus preserving their dead bodies, we were informed, that soon after they are dead, they are disemboweled, by drawing out the intestines and other viscera; after which the whole cavity is stuffed with cloth; that, when any moisture appeared, it was immediately dried up, and the bodies rubbed all over with perfumed coca-nut oil, which, frequently repeated, preserved them several months after which they molder away gradually.”1

Funerary practices vary greatly across cultures. For Western cultures, common interment practices included traditional burials in rural cemeteries, memorial parks, or mausoleums. Far less common was the Tahitian tradition of preserving important bodies for months after death. To the common eighteenth-century viewer of this image, the idea of this level of embalming may have seemed truly alien, and in the case of Webber’s illustration, affected an early influence upon the popular perceptions of Tahitian cultural customs in the West.2

Akin to corpse embalming practiced by the Ancient Egyptians, the intricate process of preparation for a

1Alex Hogg, Complete Narratives of the Following Most Important Journals: A New, Authentic, Entertaining, Instructive, Full, and Complete Historical Account of the Whole of Captain Cook’s First, Second, Third and Last Voyages. (England, 1794), 492. 2 Nineteenth century travelers in the American west made note of a similar use of scaffolds and “burial trees” by the natives of the Great

Plains as did observers of Australian Aborigine burial customs. long-term view of the body was sacred and reserved for those of high status.3 Cook and Chief Tee had actually met in 1773, during Cook’s second voyage on the HMS Resolution. 4 Warmly received by Tee, Cook and his crew created a rapport with the people of Tahiti, wishing to ensure that any return visits to the island would be fruitful and friendly.5

Webber thus captured a moment of funerary reverence, perhaps particularly poignant, given the established relationship between the voyagers and the islanders, with the embalmed corpse respectfully placed within a landscape of verdure.

As decades passed, however, Webber’s sense of documentary wonder with encountering new cultures was replaced with another viewpoint entirely. Paul Gauguin’s (1848-1903) fascination with “primitive” cultures led him to escape the lifestyle of French society in the 1890s for Tahiti.6 While there, he documented his experiences in journals and on canvas, and many art historians have pointed out that much of his writings and scenes seem carefully constructed or even plagiarized.7 He returned to France between the years of 1893 and 1895, venturing back to Tahiti once he had earned the funding for the voyage.8 He would later marry a Tahitian vahine (child bride) named Teha’amana, which benefited him by legitimizing his continued presence in the Pacific.9

Arii Matamoe (The Royal End), is speculated to be an allusion to the death of King Pōmare V (1839-

3 Douglas L. Oliver, “The Individual: From Conception to Afterlife.” in Ancient Tahitian Society. (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1974), 504. 4 Hogg, Complete Narratives, 150. 5 Ibid., 150. 6 Ziva Amishai-Maisels, “Gauguin’s Early Tahitian Idols.”, (The Art

Bulletin, vol. 60, no. 2, 1978), 331. 7 Ibid, 333.

8 Victoria Charles, Paul Gauguin. (United Kingdom: Parkstone

International, 2011), 92. 9 Elizabeth C. Childs, “Taking Back Teha’amana: Feminist

Interventions in Gauguin’s Legacy,” in Gauguin’s Challenge: New

Perspectives After Postmodernism. (New York: Bloomsbury Visual

Arts, 2018), 232. “Vahine” literally translates to “woman” in

Tahitian, however, in discussions of Gauguin’s life there the word is associated with the youth of his wife.

Paul Gauguin (French, 1848-1903), Arii Matamoe (The Royal End), 1892, Tahiti, oil on coarse fabric. Image courtesy of the Getty Center, Los Angeles, California, 2008.5

1891), the last ruling monarch of Tahiti before the French seized control in 1880.10 Contrary to Gauguin’s depiction, Pōmare had in fact not been beheaded. He had actually died of alcoholism within a decade of ceding his rule. Decapitation was not a Tahitian standard of burial.11 Art historians have instead pointed to the body of Gauguin’s work featuring biblical beheadings, as well as his familiarity with France’s prolific use of the guillotine as capital punishment.12 This completely fabricated scene of a royal death may play instead into the creation of the perceived exoticism of Tahitian mourning rituals, which had served to fascinate European voyagers since the first Cook voyage.

The garish nature of a beheading visualized horrors of the most unimaginable kind. The bright color palette evoking “tropical’’ lighting contrasts with the darkness of skin atop a white pillow in the interior scene. Illuminating the sunshine-yellow of the

10 Scott C. Allen, “A Pretty Piece of Painting’: Gauguin’s “Arii

Matamoe.” (Getty Research Journal, no. 4, 2012), 81. 11 Richard R. Bretell, On Modern Beauty: Three Paintings by Manet,

Gauguin, and Cézanne. (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2019), 60. outside world, Gauguin’s shadows in muted browns and blacks evoke a sense of day and night. The faint writing of the words Arii (nobility) and Matamoe (“sleeping eyes,” or death) emerges from the wall behind the decapitated head, evoking the pensive saying Et in Arcadia Ego (“Even in peace, there is death”).13

The two scenes share a particular focus on the openair architecture of Oceania. This was of special interest to Europeans, who seemed fascinated by the tropical climate that permitted such a way of life.14 Where Webber’s sweeping survey of a peaceful valley chosen for the purpose of displaying a chief’s corpse highlights the splendor of the natural beauty of Tahiti, Gauguin’s focus features a consideration of appropriate places to mourn and how far Tahitians are removed from Western sensibilities.

Furthermore, the two depictions are a uniquely Western binary commentary on royal or chiefly death, in particular. The death of commoners has

13 Scott C. Allen, “A Pretty Piece of Painting’: Gauguin’s “Arii

Matamoe.” (Getty Research Journal, no. 4, 2012), 75. 14 Westenra L. Sambon, “Acclimatization of Europeans in Tropical

Lands.” (The Geographical Journal vol. 12, no. 6, 1898), 589.

historically been much more simplistic, although rich traditions of reverence for every social class has been documented.15 Presumably, the death of Tee had been visually recorded as it was witnessed.16 If the crew of the HMS Resolution had stumbled upon a commoner’s death, it may likely have been the scene that was recorded instead. For Gauguin though, an active choice to fabricate a death scenario that never occurred, and alluding to it as being the death of Pōmare predicates an agenda to emphasize perceived ideas of racial and cultural difference between the West and Pacific cultures, Tahiti in particular.

15 Douglas L. Oliver, “The Individual: From Conception to Afterlife.” in Ancient Tahitian Society. (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1974), 507. 16 Ibid., 510. Reflecting on these disparate images allows viewers to contextualize a complex history. Political and cultural structures of Tahiti changed radically in the century after Cook, as Western influences permeated the entire region of Oceania. Can we quantify just how powerful early imagery of cultural practices was for those who saw it? Is it possible to understand just how impactful late nineteenth-century works were on effecting the actions of governments, and other effectors of change like missionaries, tourists, indeed, people like Gauguin himself? The work of Pacific historians, anthropologists, and cultural practitioners continues to probe at the heart of this conundrum. What spoke to me, in the lines and brushstrokes, was a chance to bridge two centuries and contemplate how imagery can dictate the reception of cultural customs–real or imagined.