4 minute read

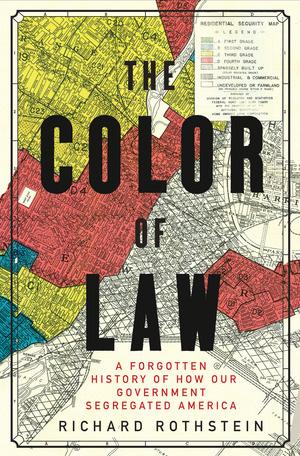

The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America

By Troi Bachmann, Director of Field Advocacy

America has a long history of civil rights disenfranchisement, and this year was no different. In addition to the challenges presented by COVID-19, a summer of civil unrest followed the death of George Floyd at the hands of police officers. Organizations across the country, including the National Association of REALTORS® (NAR) and NC REALTORS®, are now grappling with the legacy of individual and institutional racism within our nation. NC REALTORS® released a statement affirming its commitment to private property rights and homeownership for all—regardless of race, color, religion, sex, handicap, familial status, national origin, sexual orientation or gender identity. “Without productive, forward-looking engagement of all persons, we won’t come out of this painful time in our state and nation better. Racism has no home in North Carolina,” the statement read.

Moved to contextualize the legacy of race in real estate, the Government Affairs Department of NC REALTORS® delved into the history of American housing by reading The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America by Richard Rothstein. The book outlines the origins of housing policies and programs at the federal, state and local levels designed to disenfranchise and segregate African Americans. The ensuing discussions deepened our knowledge of the impact of race in housing and the challenges that African Americans face throughout the country. “It was great to see our government affairs team so interested in understanding the history behind the issues in which we are still engaged today,” reflected Mark Zimmerman, Senior Vice President of External Affairs.

The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America by Richard Rothstein published by W.W. Norton in 2017.

Photo courtesy of the Economic Policy Institute.

Most REALTORS® are familiar with blockbusting and steering and how they affect Black American homeownership. Rothstein does not limit his research to these topics. Many of the systems that we see today as equalizers in housing opportunity—public housing, tax benefits, local zoning ordinances, etc.—were created with racially restrictive qualifiers that intentionally blocked access to homeownership for Black Americans and segregated communities that were previously integrated. For example, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) was formed in 1934 by President Roosevelt and Congress in order to assist middle-class renters in purchasing their first homes during the Great Depression. Mortgage insurance would only be extended to white Americans purchasing homes in all-white neighborhoods. Despite their ability to pay for the same homes as white Americans, Black Americans were locked out of the housing market and the benefits of homeownership. The FHA Underwriting Manual even suggested a number of ways to intentionally segregate white neighborhoods from black neighborhoods, like building highways or concrete walls as barriers between neighborhoods.

Rothstein includes moving individual accounts of the discrimination Black Americans faced, as well. One of the most striking accounts is that of the Wade family’s experience in 1954. Andrew Wade—an African American, Korean War Navy veteran—and his wife were able to purchase a home from Carl Braden, a white man and activist in Louisville, Kentucky. Braden purchased a home in a white, middle-class community and sold it to the Wades. When violent protesters appeared as the Wades moved in, police monitored the destruction of the Wade family’s new home, culminating in the use of dynamite. Instead of arresting the white neighbors who perpetrated the violence, the police arrested Andrew Wade for “breach of the peace,” and a grand jury indicted the Bradens for “stirring up racial conflict by selling the house to African Americans.” These occurrences were not isolated to the 1950s and 1960s. This state-sponsored or tolerated violence continued well into the 1980s.

Andrew Wade and his family stand in front of their Shively, Kentucky home after it was damaged by rocks and rifle shots. The house was later bombed on June 27, 1954 by locals who did not want an African American family living in a white neighborhood.

Photo courtesy of Enerow.net.

Where does this leave us, then? While private discrimination absolutely played a role in the realities we see today, racial segregation in housing was largely created and enforced by federal, state and local policies. As such, Rothstein argues that as a nation, we are constitutionally bound to remedying these wounds. This history has tangible effects today. According to research from NAR, there was a 30 percent gap in homeownership rates for Black Americans compared to white Americans from 2016 –2019. Among his suggested remedies, Rothstein highlights revision of federal housing subsidies, civil rights lawsuits and bans on exclusionary zoning. More practically, Rothstein points to education of the general public as a holistic approach to correcting the ills of the past.

For the last 50 years, REALTORS® have supported the Fair Housing Act and stood for the principle that all who can and want to purchase a home should be able to purchase the home of their choice. To achieve that goal, we, as real estate professionals, must educate ourselves on the results of segregation in our markets and reflect on how to address these barriers for people of color. As we think about the changes that COVID-19 has brought to our world, we should consider how we can continue to open doors of opportunity to all members of our communities. REALTORS® strive to open doors for so many—let’s open them even wider in the coming years.

Join the Discussion

If you are interested in hosting your own discussion group centered on The Color of Law, email Troi Bachmann at tbachmann@ncrealtors.org to request a copy of a discussion guide.