5 minute read

WEATHER OUTLOOK

by NCBA

By Don Day, Jr., Meteorologist

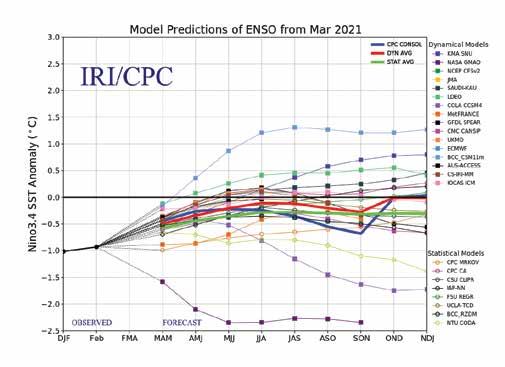

A big question headed into the summer season will be the status of the La Niña weather pattern that has dominated weather patterns across the nation since the spring and summer of 2020. The colder subtropical Pacific waters have left a large part of the central and western U.S. in a drier than normal weather pattern in 2020 and into the beginning of 2021. While the impacts of La Niña are not as noticeable from the Great Lakes to the East Coast as in the central and western states, La Niña can still impact weather patterns in those areas, especially regarding an increase in severe weather and an uptick in tropical storm and hurricane activity along the Gulf and East Coast. There are areas of the nation where we have concerns about drought conditions continuing and parts of the nation that may have too much rainfall as we head in the spring and summer seasons. The forecast for summer of 2021 will rely heavily on whether La Niña will persist, fade or head into a weak El Niño by the end of summer. All indications suggest La Niña will persist through spring, summer and early fall. If this is the case, then the tendency for drier than normal conditions over parts of the central and western states will continue. La Niña patterns usually last for around a year, but near or during solar minimums (solar minimum in early 2020), La Niña patterns can last up to two years. The adjacent graphic shows the most recent forecast for La Niña/El Niño through summer and the start of the winter season. The solid green line (average of all the modeling) stays below the zero line which indicates at least a weak La Niña will persist through summer and into the fall season and perhaps into the early 2022. If La Niña persists, even in a weaker state than in 2020, the overall patterns we observed during the summer of 2020 may continue into 2021.

Advertisement

Without a doubt, the areas of the nation most impacted by La Niña have been the western states as well as the far western Corn Belt. Those areas had a very dry 2020 and the start of 2021 has continued those trends with only a few exceptions. On the flip side, we have observed wet conditions in some areas, especially in parts of the southeast. The graphic below shows the soil moisture deficits right at the end of winter. The green areas show above normal soil moisture, white areas near normal and brown/red colors where it is the driest. While the large and very wet storm that hit parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Nebraska, Kansas and South Dakota in March helped those areas erase some of the deficit, you can see that a large part of West is in drought with some dry areas in the western Corn Belt.

Historically speaking, La Niña patterns usually bring drier conditions to the west and central areas of the U.S. and this past year was no exception. In the southern areas of the U.S. and parts of the southeast, the historical trends suggest above average precipitation during La Niña as well as an enhanced threat of severe weather: hail, heavy rain, tornadoes and tropical activity. Therefore, as we look ahead into the spring and fall of 2021, if La Niña persists, we will experience similar temperature and precipitation patterns across the U.S. like we observed in 2020. This does not mean the weather will be the exactly the same for your area as last year but rather the “tendencies” will be similar; drier in the West and parts of the central U.S. and more wet in the south and southeastern states.

Despite the stormy March pattern that did bring relief in dryness for some areas of the central and western U.S., it was only enough to put a dent in the drought conditions. For the drought areas of the West, late spring and early summer precipitation needs to be above average to erase the drought completely and if La Niña persists in some form that will be hard to accomplish. Although most La Niña patterns last only a year or so, stubborn La Niña patterns can last up to two years. It appears that we have a stubborn La Niña persisting through 2021. One potential bright spot for the very dry western and southwestern states may be a better rain producing monsoon season. From June through July in Arizona, New Mexico, Utah and parts of Colorado, there is a natural flow of moisture from the South that brings heavy rain producing thunderstorms. In July and August, this pattern expands more northward into all of Colorado and parts of Wyoming, Nebraska and Kansas. In 2020, the monsoon was very weak and was part of the issue

with last year’s wildfire season. However, there are some hints that this year’s summer monsoon may be a bit more productive which would be good news for rangeland conditions. The graphic below shows the tendencies for precipitation from June through August 2021. The model sees what should be expected if La Niña persists. Dry (brown) in many areas of the central, west, Corn Belt and Northern Plains, while wet conditions (green) in parts of the east and southeast. This is remarkably like what was observed in the summer of 2020. Unless there is a major shift in sea surface temperatures (turning warmer) in the subtropical Pacific late this spring (unlikely) then beef producers in the central and west need to prepare for drier than normal conditions again this summer while beef producers in parts of the east and south will have adequate or above normal rainfall. It is possible that the La Niña of 2021 may be weaker than 2020, which would mean the extremes (dryness or wetness) may not be as intense. However, even with a weaker La Niña in place the tendencies will remain the same as the past year.

LET’S BUILD YOUR LEGACY