5 minute read

Weather Outlook

by NCBA

Summer Changes Due to the Loss of La Niña

By Matt Makens Atmospheric Scientist

Advertisement

La Niña is pretty much done. Now onto a neutral pattern before El Niño establishes itself. Depending on your perspective and how each affects your operation, this may come with cheers or jeers. La Niña creates widespread drought for the American West and Plains, yet El Niño can increase drought for the East and far North depending upon the season; I'll have more on that in a moment.

Let's walk through some brief details about where we are and where we are going. As of March, La Niña is gone in the sea surface conditions — the ENSO region warmed quite a lot in the late winter. (The equatorial Pacific Ocean is colder than average during a La Niña and warmer than average in an El Niño.)

However, moments of La Niña continue in the atmosphere, and the atmosphere's response will be delayed for some time, as it takes a while for the atmosphere to couple (work in tandem) with the ocean. In February, the atmosphere was in one of its strongest La Niña moments of the entire event despite the sea below warming out of La Niña. So, just because La Niña is gone from the ocean conditions does not mean the storm pattern around the country can't behave like it is still in La Niña.

We do know the drought this La Niña has spread across the country, and doing away with both will be largely a good thing. The drought monitor, which was released during the same week as La Niña was declared finished in the ocean, shows the ongoing drought footprint across a lot of territory, especially the Central and Southern Plains (see top image):

Although it is safe to say we are turning the corner and the worst of the drought is behind us, the Southern Plains still need a lot of water to catch up. Plus, we will see less drought; not to say no drought. I've attached an image (bottom) of the past three years' moisture deficits to illustrate how far into the hole the La Niña pattern put us.

Hard to argue that the recovery for the central U.S. will take time, considering most of it has had 1-2 feet of water deficits in the past three years.

Hard to argue that the recovery for the central U.S. will take time, considering most of it has had 1-2 feet of water deficits in the past three years; dark reds on the map indicate at least 16-inch deficits. Plus, notice how Northern California and Southern Oregon remain in a deep hole despite the wet pattern for some of those areas this winter and early spring.

So, where are we going now that La Niña is on the way out?

The odds increase to more than 60% for El Niño later this year in the ocean conditions, but there is likely a delay in the weather pattern coupling with that ocean condition. That forecast is based on computer simulations and recent trends. To help verify the computerized outlooks, we can find clues supporting El Niño's development from real-world observations.

It is hard to ignore clues like the current precipitation pattern around India and South America; both indicate El Niño should be in place later this year. Lightning data in the tropical Pacific is also helpful as an indication that El Niño will arrive. There's also support for El Niño's development from the atmosphere's behavior near New Zealand and Alaska. I'd like to see some shifts around Hawaii to "lock it in" for an El Niño to take over sooner rather than later.

Bottom line — clues in the weather pattern indicate El Niño establishes itself later this year. Let's not put the cart in front of the horse, though. We still have a period of neutral conditions to get through before ultimately seeing if El Niño takes hold. To be in a neutral pattern, in a way, takes the extreme cases out of the mix; it doesn't focus on specific regions — like how La Niña hits the West with drought. Once we see El Niño taking control, we start to see the extreme cases focus on specific regions again. I'm not implying we will have El Niño fully in place already by this summer. Still, I created the mapping below based on those phases to illustrate how El Niño versus neutral conditions impacts summer precipitation. That’s a lot more potential for water for many folks if El Niño can develop quickly. And I should mention that several oscillations beyond El Niño and La Niña impact our weather, but for the sake of illustration, I think you get my point on the impact El Niño can bring.

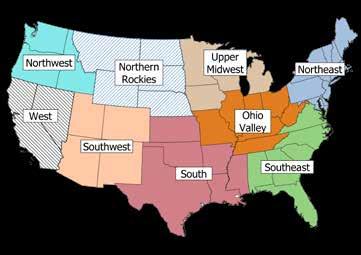

Now that we are turning the corner on the drought-plagued weather pattern of the past several years, there is a lot to be watching. As I see it, the data indicates a neutral weather pattern for this summer with El Niño gaining strength, which will lean warm and dry for some, but not nearly as dry as the past couple of summers. The regional-specific outlook for this summer is as follows.

June through August 2023

We will have just the hint of La Niña’s remaining memory left in the weather pattern, although it is a neutral summer to begin and with increasing nudges toward an El Niño pattern to finish.

Northwest: Any remaining influence from La Niña’s weather pattern, plus the cooler water along the coast, will keep the area drier than average for the season; driest the farther north. A stronger El Niño will help deliver more precipitation and cooler temperatures. Temperatures will break even for Washington and Oregon, but odds favor a warmer-than-normal summer for Idaho.

West: After an incredibly wet winter and periods of more moisture in spring, the summer will be less extreme; near-normal rainfall is expected except for northern Nevada. Temperatures will be average for northern and central California but warmer than typical for the Central Valley and Southern California, as well as most of Nevada.

Southwest: The ultimate strength of El Niño will influence the monsoon throughout the summer. A normal monsoon is expected for Arizona and New Mexico but slightly drier-thanaverage parts of Northwestern Colorado and Northeastern Utah. Temperatures will be warmer than average.

Northern Rockies: A drier than average summer, but only marginally for the region. The driest will be far northern/northwestern Montana; meanwhile, the Plains have equal chances and will likely break even. Temperatures will be warmer than average for the driest areas, near normal on the Plains. Should El Niño kick in, the mountainous areas will be cooler than average with quite a bit more moisture.

South: Soil moisture will continue a slow recovery from southwestern Kansas to western Texas. Precipitation chances are near normal, yet temperatures warmer than average will increase the evaporation on those already dry soils. Eastern parts of the region will be wetter than normal, with warmer-than-normal temperatures.

Upper Midwest: Some wetness will favor Michigan; otherwise, a breakeven summer with near-normal precipitation and temperatures and some pockets of drought possible in Iowa. Should El Niño develop more quickly, most of the region will end up drier than average.

Ohio Valley: The eastern Corn Belt will have moisture and the Ohio and Tennessee Valleys; elsewhere, expect near-normal precipitation. Temperatures will be near normal to slightly warmer than average through August.

Southeast: Areas of surplus moisture decrease farther south. Conversely, temperatures will be warmer than average the farther south, too. Should El Niño increase quickly, it’ll act to dry things out, and the season will end normal to drier than average.

Northeast: Unless El Niño kicks in, a normal to wetter-thanaverage summer with warm temperatures is expected. Drier conditions will result if we see a more rapid transition.