Gaebryl Vives

NC State student and Extension program assistant, Family and Consumer Sciences

Stories from NC State’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences

Entomologist Steve Frank’s passion for problem-solving helps shape future scientists and urban forests, ensuring that cities will continue to benefit from the shade and beauty of healthy trees.

A group of dedicated people across the state are bringing highspeed internet and advanced AI technology to our research stations and field labs in a collaborative effort to move our food system into the future.

The NC State Plant Breeding Consortium boasts more than 65 faculty and research associates laser-focused on addressing global challenges in food security, nutrition and agricultural sustainability by cultivating high-yielding, disease-resistant plant breeds.

After a century of history-making research, education and Extension, the departments of Crop and Soil Sciences and Prestage Poultry Science are primed to take their fields into the future.

Everything came into focus after Gaebryl Vives began volunteering at NC State Extension’s Briggs Avenue Community Garden in Durham. Read the story online. go.ncsu.edu/gaebryl-vives ONLINE EDITION go.ncsu.edu/CALSMagazine

Digging In

From the Archives

On the cover > (L-R) Kathyrn Polkoff of Hoofprint Biome, Jevon Smith, Trevor Quick and Brendan Riddle (on ladder) from CALS IT, at Reedy Creek Educational Units where an expansion of fiber optic cable has opened the door to new ag tech research.

In the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, leading in the field truly starts with our incredible people, innovative programs and strong connectivity. We are passionately committed to investing in the people of North Carolina. By focusing on recruiting, retaining and developing top-notch students, faculty and staff, we’re fostering a sense of belonging that is the cornerstone of our vibrant community.

I’m thrilled to share that our enrollment numbers in CALS are on the rise! This growth reflects our dedication to providing a practical, forward-thinking education. To continue leading the way, we’re adding a new faculty cluster focused on artificial intelligence (AI) in agriculture. We hope to soon include vital training in AI in our curriculum, equipping our students with skills that 90% of the emerging workforce will need.

Our college continues to shine in research innovation and technology, having surpassed the impressive $120 million mark in new grants and contracts once again this year. This milestone underscores our relentless pursuit of advancements in agricultural sciences and technology.

In this issue’s cover story, you’ll discover the critical investments we’re making to future-proof our farms and

food supply. We’re enhancing digital connectivity across our four field laboratories and 18 research stations in partnership with the North Carolina Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services. The cutting-edge technology and innovation we’re integrating — sensors, drones and robotics — will propel the entire agricultural industry forward.

We invite our partners to join us in these exciting ventures. By investing together in our research stations, we can conduct 21st-century research that will greatly benefit North Carolina agriculture.

I couldn’t be prouder to say that our college is strong and will continue to lead in the agriculture and life sciences industries. We’re bolstering our commitment to our people, our programs and our connectivity to stakeholders. Join us on this incredible journey and Go Pack!

Garey Fox, Dean College of Agriculture and Life Sciences

1,300+

NC State College of Veterinary Medicine leader Megan Jacob began her new role as the senior associate dean of administration for the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences in June.

Jacob previously served as a professor and director of college support and external relations for the College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM). Jacob has been active with the Food Animal Initiative, a partnership of CALS and CVM, since its inception. She has met regularly over the past year with faculty leaders in both colleges to generate new ideas and momentum for the initiative.

Jacob came to NC State in 2011 after completing undergraduate work in microbiology at the University of Wyoming, and M.S., Ph.D. and postdoctoral work in veterinary pathobiology at Kansas State University. She has done extensive work in applied microbiology, studying the transmission of pathogenic and antimicrobial-resistant bacteria in food animals.

In her role with CALS, Jacob will lead critical processes, including budget planning, faculty promotion and tenure, and strategic plan execution. She will serve as managing supervisor of CALS directors of information technology, international programs and administrative communications.

“My goal is to positively contribute to CALS success by aligning resources and processes that support the college’s diverse and strategic goals,” she says.

David Crouse — a CALS faculty member for more than 25 years — was named associate dean and director of Academic Programs this spring.

“Attracting students to join CALS is just the beginning of our commitment to their success,” Crouse says. “I am excited to lead Academic Programs as we continue to integrate academic guidance with personalized mentorship, and empower our students to navigate the critical transition to university life.”

Crouse most recently served as the associate department head and director of undergraduate programs for the Department of Crop and Soil Sciences. Beyond his teaching and leadership roles, he previously served as an Extension associate in animal waste management. Crouse earned his bachelor’s degree in horticultural science and his master’s and Ph.D. in soil science, all from NC State University.

The associate dean and director is responsible for enhancing students’ overall experience and implementing strategies that support the Academic Programs Office and CALS, including programs for student recruitment, enrollment, access and success.

“As a first-generation student and three-time graduate of NC State, I know that the people you meet and experiences you have as a student directly impact your life and career,” Crouse says. “My aim is to create more access to NC State for students who want to be here, and to foster connections between students and faculty — ensuring students discover what they want to do and receive the support they need to launch their careers.”

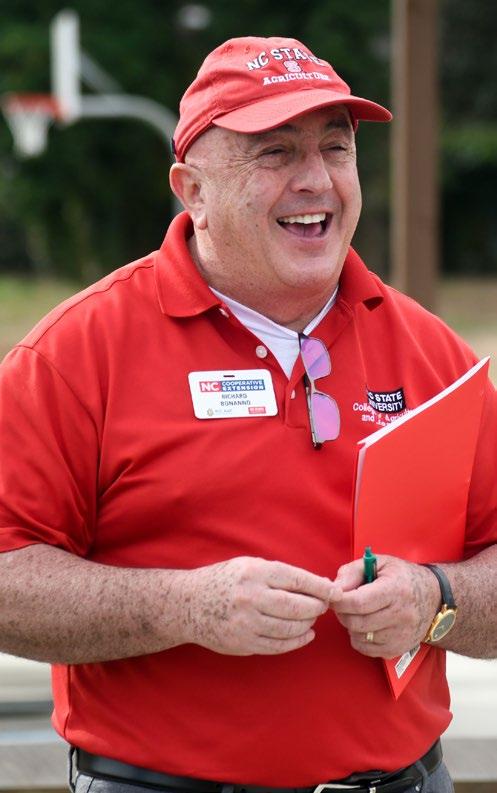

You can’t miss him. On campus and in the field, Richard Bonanno’s large smile and generous laugh are at the ready, whether he’s catching up with colleagues or working to find a solution to a funding challenge. Approachable and practical, Bonanno has helmed NC State Extension, the university’s largest outreach unit, since 2016 — and his leadership has helped the organization flourish.

This June, Bonanno announced that he will step down as director of NC State Extension and transition to a new role as executive director for the Association of Southern Region Extension Directors (ASRED) at the end of August.

“This is a bittersweet departure for our CALS community,” says Garey Fox, dean of the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. “We are sad to lose Rich’s steadfast leadership, but we are thrilled that he will continue to drive the land-grant mission forward across the Southern Region in his new position with ASRED. Extension is at the heart of our land-grant mission, and we look forward to the next chapter of NC State Extension that builds upon a strong foundation established by Rich Bonanno.”

Bonanno first came to NC State as a faculty member in 1983, serving as an Extension weed specialist and CALS researcher for vegetable crops until 1989. He then moved to Massachusetts, where he owns and operates a farm north of Boston specializing in fresh market vegetables, bedding plants and vegetable transplants. In addition, he was an adjunct professor and Extension educator with the University of

Massachusetts. Bonanno returned to NC State as associate dean and director of Extension in 2016.

“It has been an honor to work with our colleagues and communities across the university and our vast Extension network,” Bonanno says.

And the feeling is mutual.

"Dr. Bonanno has been the best Extension director in North Carolina during my 30-year career,” says Bryant Spivey, Extension director for Johnston County. “It has been evident through his work ethic and relationships that he’s built that he cares deeply for the communities we serve and for the Extension agents doing the work."

During Bonanno’s time as director, NC State Extension's annual budget increased by 37%, and he launched the ambitious 2030 NC State Extension strategic plan, which will help ensure that Extension and its stakeholders statewide continue to grow and prosper for years to come. The college will conduct a national search for a new associate dean and director of Extension. Sarah Kirby and David Monks will co-manage the role as interim associate deans and directors of NC State Extension while CALS conducts a national search.

Editor Amanda Kerr

Art Director

Patty Anthony Mercer

Staff Writers

D'Lyn Ford, Simon Gonzalez, Sam Jones, Amanda Kerr, Krystal Lynch, Justin Moore, Alice Manning Touchette

Contributing Writers

Rachel Damiani, Dee Shore

Copy Editor

Gregor Meyer

Photography

Simon Gonzalez, Marc Hall, Becky Kirkland, Trevor Quick

Videography

Chris Liotta

Digital Design

Sam Jones

Dean Garey Fox

Senior Associate Dean for Administration

Megan Jacob

Associate Dean and Director, NC State Extension

Richard Bonanno

Associate Dean and Director, N.C. Agricultural Research Service

Steve Lommel

Associate Dean and Director, Academic Programs

David Crouse

Assistant Dean and Director, CALS Advancement

Sonia Murphy

Chief Communications Officer

Megan Lybrand

Visit Us Online > cals.ncsu.edu

NC State University promotes equal opportunity and prohibits discrimination and harassment based upon one’s age, color, disability, gender identity, genetic information, national origin, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.

Send correspondence and requests for change of address to CALS Magazine Editor, Campus Box 7603, NC State University, Raleigh, NC 27695 -7603.

9,000 copies of this public document were printed at a cost of $1.84 per copy. Printed on recycled paper.

Howling Cow Creamery helped make the men’s and women’s basketball teams’ 2024 paths to the Final Four a little cooler. Carl Hollifield, director of NC State’s Dairy Enterprise System, surprised exuberant fans on March 23 as they flocked to Memorial Belltower to celebrate the men’s team reaching the Sweet 16.

With a key assist from Dean Garey Fox, his family, and a few excited CALS staffers, Hollifield handed out 1,000 cups of Howling Cow ice cream to the excited crowd. Hollifield pulled off a sweet surprise again in front of Reynolds Coliseum on March 25, where he and his ice cream friends handed out another 1,000 cups to fans after the women’s basketball team sealed their trip to the Sweet 16. Both teams ultimately made it to the Final Four.

“Howling Cow ice cream is such an integral part of the NC State experience, we wanted to give back to our basketball fan family and celebrate the men’s and women’s teams making it to the Sweet 16,” says Hollifield.

The CALS Pack was thrilled to show support for our student-athletes — with an assist from Hollifield and Howling Cow.

Sixteen undergraduate and graduate students from the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences were honored this spring for their outstanding scholarship, leadership, research and community outreach during the inaugural CALS Awards. Fifteen faculty were recognized for teaching and advising excellence.

“Every awardee has been supported and mentored and has collaborated with people who made these awards possible,” Dean Garey Fox said during the ceremony.

The goal of the awards is to empower students to make a positive impact on campus, in the community, and beyond.

“We need to create a culture where everyone’s contributions are valued and celebrated,” Fox said. “If we can accomplish this, then we can truly disrupt for good.”

Award recipients included Anne Lindbergh, an undergraduate student majoring in plant biology, who was recognized alongside Shana McDowell, a graduate student in biological and agricultural engineering, as student of the year.

A native of West Virginia, Lindbergh was recognized as an outstanding student and leader whose “zeal for learning and ambitions for a career in science have led her to pursue all manner of learning experiences.” She has worked in three diverse labs, participating in a variety

< Sixteen undergraduate and graduate students and 15 faculty were recognized at the inaugural CALS Awards in April.

Dean Fox and Anne Lindbergh

of research projects from identifying bee species on Grandfather Mountain near Linville, North Carolina, to exploring virus-host protein interactions. She also cofounded the undergraduate Entomology Club.

Lindbergh, who earned her bachelor’s degree in May, will continue her studies this fall at NC State as a Genetics and Genomics Scholar and a doctoral candidate in the Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology.

She said her experiences as a CALS student undoubtedly shaped the path she is on today.

“I entered university with only a vague idea of what I wanted to study. While I have always loved insects, I was not aware of the variety of careers available in the field of entomology,” Lindbergh said. “Through my undergraduate coursework as a CALS student, I came to realize that the field is incredibly broad.”

“I have had the opportunity to work with wonderful mentors and peers on a variety of projects, which has inspired me to pursue graduate studies with the goal of eventually becoming a professor myself,” she noted. “I am so grateful for the opportunities I’ve received as an undergraduate student in CALS, and am excited to continue to contribute to a learning environment that promotes and nurtures curiosity.”

By Rachel Damiani

Entomologist Steve Frank can relate to undergraduates who are undecided about their career path — he was once one of them.

“I took a job in an entomology lab during my last semester in college and it sort of saved me because I had no plans,” Frank says. “Everything started to fit together. I realized I could work with plants and insects while also helping to solve problems as a scientist and professor.”

As a professor in NC State’s Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology, Frank now helps assess the health of trees in urban jungles.

An active scientist, Frank has garnered more than $10 million in research funding to study why pests are pervasive in city trees, findings he shares with arborists and landscapers as an Extension agent.

“It’s easy to say that trees and biodiversity are mostly in national parks or some big protected area,” Frank says. “But, the reality is that a lot of trees that provide the services and biodiversity that we interact with are not in forests, but in cities.”

A tree in the city has a tough life. On a summer day, city temperatures tend to run a few degrees warmer than in rural areas thanks to sidewalks and roads that store heat and radiate it back to the environment, known as the urban heat island effect.

But heat isn’t the only factor these city trees endure. Frank’s findings indicate heat attracts unwanted pests, too.

“What we’ve found is that temperature is the primary factor driving pest populations on these trees — and so we’ve then used that information to try and understand and predict the effects of climate change on forest trees,” he says.

Much of Frank’s work has implications close to home. He’s investigated gloomy scale insects on Raleigh’s second most popular tree: the red maple.

“Scale insects are literal bumps on a log,” Frank says. “They don’t have legs. They don’t have eyes. They just live under a little shell and they suck juices from the plant.”

< Steve Frank specializes in entomology and urban landscapes.

Using satellite images and data loggers, Frank has compared red maple trees just a few blocks away from one another that differ by a few degrees in temperature. He discovered that an increase of just 2 degrees in temperature increases the gloomy scale population by 300 times.

“They cover the entire bark of the tree and they’re sucking on the resources that the tree needs to grow and survive,” Frank says.

Frank’s findings have long-term implications for climate change: city trees give scientists a glimpse into how future warmer temperatures could affect forests. At the same time, Frank has used his findings to make recommendations that can prevent unnecessary tree deaths now.

“We’ve developed thresholds where if there’s a certain amount of impervious surface around a site where you want to plant a tree — if it exceeds 30% — then you shouldn’t plant the red maple because it will be too hot and dry,” Frank says.

After hearing his guidelines, the City of Raleigh reduced its planting of red maples and diversified to other tree species. Frank enjoys working closely with arborists and landscapers across the state to make a difference.

“They’re super jazzed to find anything that will help them maximize the number of trees they plant and the number that survive with the least maintenance,” he says.

It’s this collaboration and creative problem-solving that initially drew Frank to academia.

As a mentor, Frank often helps solve problems of a different kind — whether helping new faculty navigate unexpected aspects of their job or graduate students become independent scientists. He especially relishes the opportunity to foster undergraduates’ courage to solve problems.

“You have got to just try it,” Frank says. “You’re going to fail sometimes — a lot of times — and that’s okay. You try to tackle things as best you can.”

By Sam Jones

'Twas a week before Christmas, when all across the state, not a creature was stirring ... except the CALS Research Computing Team at NC State University. Armed with tractors, excavators and spools of fiber optic cable, Jevon Smith, Brendan Riddle and Trevor Quick spent a chilly weekend in December of 2023 building fiber optic pathways to bring high-speed internet to the Horticultural Crops Research Station in Castle Hayne, North Carolina.

“The technology we’re installing isn’t commonly found on farms, it is much more likely to be seen in a Google data center,” Smith says. “Our work has novel applications in many ways — it’s very experimental for all of us.”

The goal of the Research Computing Team: lay critical tech infrastructure necessary to future-proof farming in North Carolina.

Had Smith, Riddle and Quick stopped to contemplate how they came to be installing fiber at a research farm on a weekend before Christmas, they may have had to think back to the 1800s.

Agricultural research has been conducted for nearly 150 years in North Carolina at what were once called Experiment Stations. Today, NC State, in partnership with the North Carolina Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services (NCDA&CS), runs the secondlargest research station network in the country, with 18 stations and four field laboratories that range in size from 101 acres to several thousand, each representing unique climate and soil conditions.

Most of NC State’s plant breeding research happens at research stations. As “living laboratories,” the stations enable researchers to investigate crops, forestry and environmental concerns, livestock, poultry, aquaculture and even weather patterns.

Over the lifetime of North Carolina’s research stations, advancements to equipment and technology have revolutionized how food gets to our tables and how rural communities operate.

Without access to broadband internet, that work is at risk of falling behind.

In 2022, the federal government allocated more than $42 billion to the Broadband Access, Equity and Deployment (BEAD) Program to build infrastructure and increase broadband adoption equitably nationwide.

The program prioritizes unserved communities (defined as receiving less than 25 Mbps) and underserved communities (defined as receiving 25 to 100 Mbps).

An estimated 22 million Americans live in unserved communities. North Carolina has the ninth-highest percentage of unserved residents, totaling nearly 1.3 million people, according to new BroadbandNow data. In terms of NC State’s research stations, 12 out of the 22 research stations and field labs are underserved or unserved.

Because research depends on good data, and good data today relies on internet connectivity, broadband allows researchers to deliver the most high-impact, relevant recommendations across the state. Luckily, a dedicated group of people at NC State is bringing our research stations into the modern era, one line of fiber optic cable at a time.

“Massive data collection and analysis are now required at the field level to provide the next generation [with] decision-making tools, predictions and variety development,” says Steve Lommel, director of the North Carolina Agricultural Research Service and associate dean for research in CALS. “That’s why fast fiber is needed at every station.”

To bring broadband to North Carolina’s research stations and field labs, a motivated group of collaborative individuals across NC State and NCDA&CS has been working toward a common goal: Get every research station and field lab connected to high-speed internet. Nearly half of the research stations have at least 100 Mbps of broadband speed, but the ultimate goal is to get every station up to 1 Gbps to align with the highest standard.

But the fiber project doesn’t just stop at highspeed internet, which will bring fiber optic cables to the “front door” of every station. That’s just phase one of a seven-step process.

“Nothing else can happen without the initial connection to the internet. But once it does, everything becomes possible,” Smith says.

“We don't just need this on one station, we need it across our entire system so that we can work on projects from the mountains to the coast and serve all our clientele,” says Loren Fisher, director of research stations and field labs at NC State.

And a digitized research station network won’t just meet today’s demands; it will position the state’s researchers to meet the demands of the future. The dynamic nature of both technology and research necessitates flexibility. Smith and his team are building project- and tech-agnostic systems so the stations can accommodate anything a faculty member might need or a farmer might ask about.

Internet of Things (IoT): An ecosystem of devices connected through the internet.

Examples of IoT in agriculture:

> Greenhouse automation

> Storage climate controls

> “Smart” irrigation

> Livestock monitoring

> GPS and precision agriculture

> In-field crop sensors

> Drones

> Robotics and autonomous machines

1. Internet Connectivity:

Bring 100 Mbps to 1 Gbps of broadband speed to the “front door.”

2. NC State Campus Connectivity:

Install VPN networks for data security compliance and access to on-campus resources for station staff.

3. Telephone Service:

Equip all stations with reliable and secure phone service.

4. Digital Multimedia:

Equip all stations with the necessary technology to access virtual meetings and utilize digital resources for in-person communications.

5. Video Security:

Install video cameras at all research stations to enhance the protection of valuable farm equipment and the safety of station staff.

6. Field Network Access and IoT Capacity:

Extend broadband access around research stations via fiber or point-topoint wireless to enable IoT use.

7. Edge Computing Capabilities:

The ability to remotely run artificial intelligence and machine-learning workloads on the stations.

Research Station and Field Lab

Internet Connectivity

(7) UNSERVED (1–24 Mbps)

(5) UNDERSERVED (25–99 Mbps)

(10) HIGH-SPEED (100 Mbps–1 Gbps)

“Our stations can be a testbed for technologies that benefit growers just like any other management practice NC State faculty study at the stations,” says John Garner, superintendent of the Horticultural Crops Research Station in Castle Hayne.

“It’s about providing value to the agricultural industry in our state.”

It’s also about being able to meet biosecurity and chemical security regulations and expanding the ability of NC State faculty to pursue new research funding through improved access to data security. Ultimately, though, it’s about feeding people.

“If we are going to continue to feed a growing population, with fewer resources like land, water and labor, those of us working in agriculture must improve our efficiency. Technology and research are the only ways to achieve that goal,” says Teresa Lambert, director of the Research Station Division for NCDA&CS.

“If we are going to continue to feed a growing population, with fewer resources like land, water and labor, those of us working in agriculture must improve our efficiency. Technology and research are the only ways to achieve that goal.”

Teresa Lambert Director, Research Station Division, NCDA&CS

< A temperature sensor controls the climate for seed storage at the Central Crops Research Station in Clayton. With high-speed internet and campus connectivity, sensors can be operated and fixed remotely.

To help prepare North Carolina for the future of agricultural research, NC State and NCDA&CS have partnered with MCNC, a nonprofit organization that owns and operates one of America’s longest-running regional research and education broadband infrastructure networks. North Carolina’s education, research, library, healthcare, public safety and other public institutions are all connected on the same network through MCNC.

Smith explains that the Research Triangle didn’t become what it is today by accident. The ability of Duke University and UNC-Chapel Hill to develop world-renowned cancer research was in part made possible by being connected to a secure network, established by MCNC, through which they could share information.

“We’re doing the same thing for agricultural research,” Smith says.

MCNC conducted an engineering review of every research station to assess the feasibility and cost of bringing in fiber. The Central Crops Research Station near Clayton, for example, was on dial-up internet until 2018, when MCNC connected the main administrative building to fiber. Dial-up only provides 0.056 Mbps compared to the 25 Mbps that defines an area as unserved.

Now, Central Crops is one of the most advanced research stations in the system as one of only three with any IoT capacity or a campus VPN connection. High-speed broadband at the station makes it possible for faculty across disciplines to conduct advanced crop stress research, breed more resilient plant varieties, and monitor major agricultural pests, all with better, more accurate data.

“The high-speed connection that we have at Sandhills is what allows that midnight data transfer to take place. If they didn’t have a broadband connection, you could forget it.”

Chris Reberg-Horton Director of Resilient Agricultural Systems N.C. Plant Sciences Initiative

Brynna Bruxellas (left and top of opposite page) is the lead UAV pilot for the Drone Pilot Project. Her research uses UAV imagery to help rate and evaluate turfgrass quality. She’s working toward a master's degree in crop science, as well as graduate certificates in GIS and Ag Data Science.

The Drone Pilot Project is a collaboration between the N.C. Plant Sciences Initiative, Plant Breeding Consortium, NC Agricultural Research Service, USDA Agricultural Research and NCDA&CS. The N.C. PSI Compute Team is made possible by the hard work of Rob Austin, Amanda Hulse-Kemp, Anna Locke, Jacob Fosso Tande and Jinam Shah.

People have been researching the use of drones in agriculture for over a decade.

“A lot of the basic things that we have to quantify can be done so much faster from a drone,” says Chris Reberg-Horton, a professor in the Department of Crop and Soil Sciences and the director of resilient agricultural systems for the N.C. Plant Sciences Initiative.

Plant breeders can use data collected from drones to quantify the traits they are breeding for, such as drought tolerance or growth rate, and identify, diagnose and treat stressed plants. But Reberg-Horton emphasizes that anyone doing digital ag research can only work at stations with internet connectivity. He says that some crops and regions are being left out as a result.

Jeremy Martin, superintendent of the Sandhills Research Station in Jackson Springs, explains that the Drone Pilot Project started at his station not only because it’s one of a few with high-speed internet connectivity, but also because of the area’s sandy soils, which are ideal for

intentionally stressing plants through nutrient and water limitations.

The N.C. PSI Compute Team leading the Drone Pilot Project aims to develop a synergistic, accessible system of drone data collection and analysis that any researcher can use. The idea is for research station staff to conduct weekly drone flights of every research plot at the station, collecting every primary type of data used in plant trials. Field researchers have agreed on a standard set of sensors for drone flights that includes camera imaging and multispectral imaging calibrated to the light plants respond to.

After a day’s flight, the station staff member loads the data on a computer at the station into an app that RebergHorton’s team has developed. At midnight, the data migrates back to campus to be processed and stored.

“The high-speed connection that we have at Sandhills is what allows that midnight data transfer to take place. If they didn't have a broadband connection, you could forget it,” Reberg-Horton says.

After a successful transfer, a second app developed by the N.C. PSI Compute Team stitches as many as 20,000 images from the previous day’s flight together into one large image of the entire station. The app then calculates indices of interest that get stored in a database for access at any time. The intention, Reberg-Horton says, is to eventually have an archive of every research station every week during the growing season in the hopes of answering both anticipated and unanticipated research questions.

“Drones are just the tip of the iceberg,” Reberg-Horton says. “Not everything can be captured from the skies. Fruit crops with thick canopies, for example, need to be imaged from the sides and below. We plan to move into data collection via ground-based robots and tractor-based imaging systems for other crops.”

Beyond drones and robots, the data those devices collect must ultimately add value for the end user. With the future in mind, Smith has left room for evolution. Eventually, the cabinets that house the internet equipment on every research station will also play host to machine-learning hardware.

“It's not only about data collection for our researchers,” Fisher says. “It's also about testing new technology that farmers can employ on their farms. And they’re already asking us questions that we aren't ready to answer and won’t be able to answer until we have high-speed internet capabilities on our stations.”

The kinds of questions growers are asking relate to the financial pros and cons of adopting new technology. Will a drone save them money on labor, chemicals and equipment? Is it as effective at managing pests and disease? Or, they may have already adopted data-generating technologies but aren’t sure how to best utilize the information or apply it to management decisions. The power of a digitized research station network is in quantifying the value of technological investments that can push North Carolina farmers into a league of their own in the global marketplace.

“AI and digital ag is the revolution of our time,” Reberg-Horton says. “It’s about NC State staying on the forefront of innovation.”

“AI and digital ag is the revolution of our time. It’s about NC State staying on the forefront of innovation.”

Chris Reberg-Horton Director of Resilient Agricultural Systems

N.C.

Plant Sciences Initiative

Investments in technological infrastructure keeps CALS on the forefront of innovation. Not only do NC State and NCDA&CS provide agricultural land and resources to researchers, but they also support the budding ag tech industry in North Carolina. Recent tech upgrades to CALS’ Reedy Creek Educational Units have opened up new possibilities for an industry partnership.

Hoofprint Biome, a startup headquartered in the NC State Plant Sciences Building, is developing probiotics and natural enzymes to improve cattle gut health and reduce methane emissions. Cattle contribute 6% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

To achieve those goals, Hoofprint Biome needed a facility capable of supporting detailed data monitoring and bovine management. The Reedy Creek Educational Units fit the bill but required significant updates to their digital infrastructure.

Following a similar model as the research stations and field labs, Jevon Smith and Trevor Quick dug a trench to lay fiber optic cables, then built a pergola to house SpaceX-Starlink servers for highspeed internet access alongside data processing technology.

“There's a lot of potential in this private sector partnership that really highlights the importance of our continued investment in connectivity,” Smith says. “Without it, none of this would be possible.”

With the newly installed equipment, Hoofprint Biome can collect real-time data using sensor technology developed in the N.C. PSI Makerspace. The device measures the hydrogen, CO² and methane in each cow’s gut via a portal-like attachment. Every 30 minutes, data from the cow’s gut is sent to a computing data processor housed on the pergola and uploaded to the cloud. Hoofprint Biome will use that information to measure the effectiveness of their nutritive solutions.

“I can now log into my laptop from anywhere to monitor methane concentration continuously from each of the cows wandering in the pasture,” says Kathryn Polkoff, co-founder and CEO of Hoofprint Biome. “This capability is something that sets NC State apart from anywhere in the world.”

Story and Photos by Simon Gonzalez

If you want a sweetpotato, you've come to the right place. North Carolina is tops in the nation for growing the healthy root vegetable. Poultry and eggs? Yep, we're No. 1 in those, too.The state's agricultural producers come in at No. 2 for turkeys, trout and Christmas trees, and No. 3 for cucumbers and hogs and pigs. And we're in the top 10 in apples and blueberries.

But raspberries? Forget about it. The flavorful little red berries don’t grow well here.

“You can’t grow raspberries in North Carolina of any commercial consequence,” according to Cal Lewis. “You can do home gardening and some small-scale things in the mountains, but our summers are way too hot for raspberries.”

Lewis, a 1977 horticultural science graduate of NC State University’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences — and recipient of the college’s Distinguished Alumni award in 2017 — is one of the top berry growers in the state. He owns and operates Lewis Nursery and Farms, a third-generation family farm located in Rocky Point in Pender County, about 18 miles north of Wilmington. His strawberries, blueberries and blackberries can be found in produce aisles across the state and region.

What he says about raspberries is true, especially in the coastal Southeast. They thrive in the cool climates of California and Washington; heat and humidity are not their friends.

Or at least, that used to be true. In conjunction with NC State researchers and Extension specialists, Lewis is now producing a successful crop on the Carolina coast.

“I now joke with people this time of year,” Lewis says. “I ask them, ‘Where in this hemisphere can you get raspberries?’ Anybody that knows anything about raspberries, they’ll say Mexico and California. And I’ll say, ‘Rocky Point, North Carolina.’”

Lewis regarded the conventional wisdom about not being able to grow raspberries in North Carolina not so much as a statement of fact but almost as a dare.

Source: Dorn, T. (2023). North Carolina 2023 Agricultural Statistics. U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service, North Carolina Field Office. N.C.

#1 in the nation

Poultry & Eggs, Sweetpotatoes, Tobacco

#2 in the nation

Turkeys, Trout, Christmas Trees

#3 in the nation

Hogs & Pigs, Cucumbers

Top 10 in the nation

Blueberries, Apples

Can it Be Done in N.C.? Raspberries

“About three or four years ago, we started having an interest in producing raspberries,” he says. “I love raspberries, number one. And I also wanted to fulfill that fourth berry category here in North Carolina.”

Like his father and grandfather before him, Lewis thrives on innovation. Lewis Farms was a pioneer in the plasticulture method of growing strawberries in North Carolina, which helped revive the industry in the state. He began growing the berries in high tunnels in the winter, giving him a crop in the off season. He saw an opportunity for agritourism, and his retail market on Gordon Road in New Hanover County is always busy with local families and tourists picking their own berries and enjoying some tasty ice cream.

Through his association with Driscoll’s, a Californiabased company that sources berries globally, Lewis learned of a method of growing raspberries called long cane. He found out that raspberry primocanes grown in containers in a cooler climate can be transported to a warmer area and potentially produce a good harvest.

He approached NC State Extension small fruits specialist Gina Fernandez and suggested a collaboration to conduct on-farm trials. Fernandez also knew of the long-cane method, and was eager to try it in North Carolina.

“It’s something that in a large part he initiated and funded,” Fernandez says. “He donated land, plants and labor for the work at his farm. His goal was to have Extension help develop the system for longcane raspberries for the state’s growers.”

Lisa Rayburn, an Extension area agent for commercial horticulture and Fernandez’s graduate student, worked with Lewis to establish the first crop. She remains a frequent visitor to the farm.

“The long-cane production system has been widely adopted in Europe and we wanted to see if it was viable here,” Rayburn says.

In a long-cane system, the raspberry plants are grown for the first year in a nursery in a cool climate. The plants are shipped to the grower in the winter to be set out in pots in high tunnels. The plants are harvested in the spring before the heat of summer has a negative impact on berry size and quality.

“We put them out in our enclosed protective tunnels in January,” says Lewis, who sources his plants from Quebec, Canada. “We harvest fruit in April and May, and we discard the plants after that. Traditionally, raspberries are grown as a perennial crop. In the Northwest and California, they grow in the soil for several years. This is an alternative way that allows us to have raspberries here in North Carolina.”

It required a significant investment in time and money. He had to purchase the plants and construct the high tunnels, which need a ventilation system to ensure the raspberries are warm in the winter and cool in the spring. He also worked with Rayburn and her team to manage moisture and nutrient levels in the growing environment.

“I’d be remiss if I didn’t say that this is a huge challenge,” Lewis says. “It takes quite a lot of expertise in growing in a substrate environment versus soil. And it’s quite an expensive proposition. It’s not for the faint of heart. But we’ve proven it can be done.”

Lewis also had to be willing to share the results with other growers. NC State research is designed to be disseminated through Extension to interested growers throughout the state. As a proud alumnus of CALS and as the son of Everette Lewis, a former NC State Extension agent, he sees sharing the knowledge as almost a duty.

“I wanted to be able to prove that we could do it and show there are opportunities commercially for people to do it,” he says. “We are an extension of Extension. As leaders of the industry, I feel an obligation to share my knowledge with the smaller grower.”

“I wanted to be able to prove that we could do it and show there are opportunities commercially for people to do it. We are an extension of Extension. As leaders of the industry, I feel an obligation to share my knowledge with the smaller grower.”

Cal Lewis Owner/operator, Lewis

Nursery and Farms

By Krystal Lynch

Joseph Gakpo believes the future of his native Ghana lies in its agricultural advancement. Steady, focused and mission-minded, he’s carving his path at NC State University while pursuing advanced agricultural education and genetic engineering degrees from the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

With a background in journalism and a passion for agricultural development, Gakpo leverages his knowledge and experience to make a difference in Ghana and the international community.

Gakpo holds a bachelor’s degree in agricultural biotechnology from Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology and a master’s in communication studies from the University of Ghana. In 2020, he received the International Federation of Agricultural Journalists/ALLTECH International Award for Leadership in Agricultural Journalism.

After arriving at NC State in 2021, he earned a master’s in liberal studies with a concentration in agriculture and communication. A 2022 University Graduate Fellow, Gakpo is currently pursuing a doctoral degree

in agricultural education with a minor in genetic engineering and society.

We caught up with Gakpo to learn about his journey from journalism into agriculture.

How has your journalistic work impacted Ghanaian communities?

I traveled through rural Ghanaian communities and reported on agricultural production challenges and rural underdevelopment. Some communities struggle to obtain potable water, harness electricity and build sound educational infrastructure. I also write about how climate change and pest infestation affect agriculture to motivate national leaders to address these challenges.

I reported on Nyitavuta in the Volta Region, which had no clean water, electricity, sanitation or road infrastructure. An American philanthropist responded by providing solar lamps and panels, and another good Samaritan installed a borehole for clean water. In an Oti Region community, students studied in deplorable conditions. Several Ghanaians in the U.S. got involved by building classroom blocks.

Why did you form the Opoku Gakpo Foundation?

In 2018, I won the MTN Heroes of Change Award, honoring individuals who improve lives in Ghanaian communities. I used the monetary award to form the Opoku Gakpo Foundation, which enhances educational activities in rural Ghana. The foundation and its supporters provide rural students with educational supplies like books, school bags, uniforms and other necessities. It’s a small foundation, but I hope it will grow.

Why did you choose NC State to further your agricultural education?

I’m a journalist who covers agriculture in Ghana. I came to CALS to deepen my knowledge and gain skills in agriculture. I will return to Ghana to use my education to enhance the country’s agricultural sector by helping strengthen the delivery of extension services to farmers.

A one-hectare cornfield in Ghana produces 1.5 metric tons on average, while a similar field in the U.S. yields 11 tons. This margin underscores the need for transforming Africa’s agricultural sector. I want to use the skills I

learn at NC State to play a role in that transformation.

Describe your research around building trust in GMO technology among Ghanaian farmers.

I’m interested in agricultural biotechnologies, including GMOs and gene-edited crops. Assistant Professor Katherine McKee and I presented a paper on GMOs, a work in progress, at the 2024 Association for International Agricultural Extension Education conference in Orlando, Florida.

The paper explores how Ghanaian scientists cultivated farmers’ trust in northern Ghana, encouraging them to try GMO seeds despite the controversial technology. The forthcoming paper explores facilitators of trust, which are vital to deploying agricultural technologies. We will recommend what stakeholders can do differently to build trust in food systems.

What did you present at the Sustainable AgriFood Technology Summit in May 2024 at NC State?

My work with Assistant Professor Katie Sanders involves understanding North Carolina consumers’ perceptions of CRISPR technology. The study

“When I return to Ghana, I’ll use my knowledge to impact agricultural production.”

revealed that many consumers seeking CRISPR information favored logical analysis and data examination. We recommend that researchers develop communication materials rich in facts and data to help North Carolina consumers make informed choices.

How would you characterize your experience at NC State?

NC State has a strong international approach to "Think and Do." I've collaborated with international colleagues and professors in my department. I attended NC State to understand how the U.S. advances agricultural practice and technology.

I'm grateful for opportunities to learn from professors Katherine McKee, Katie Sanders, John Dole, Fred Gould, Nora Haenn and AgBioFEWS Program Coordinator Dawn Rodriguez-Ward from the Genetic Engineering and Society Center. These faculty members have mentored me, and I've improved significantly during my studies.

By Alice Manning Touchette

How we continue to feed, clothe and beautify the world starts with cultivating resilience. The NC State Plant Breeding Consortium boasts more than 65 faculty and research associates actively developing new cultivars, germplasm and parental lines, making it one of the largest groups of plant breeders in any U.S. university. Their mission: address pressing global challenges in food security, nutrition and agricultural sustainability by cultivating

“We’re building a vibrant ecosystem for interdisciplinary research collaboration around the country and the world,” says Carlos Iglesias, director of the Plant Breeding Consor tium. “Through shared resources, communication and train ing for our students and partners, we accelerate the pace of genetic improvement in a wide array of crop species to boost farmers’ profitability, enable new value chains, and foster resilience to unpredictable environments.”

NC State plant breeders are responsible for some of the most successful cultivated varieties in food and fiber crops, ornamental landscape plants, and turfgrass. The examples that follow are just a taste of the hundreds of varieties developed at the prolific Plant Breeding Consortium.

Dried, cured and sold around the world, fluecured tobacco was North Carolina’s original cash crop. Nearly 50% of North Carolina tobacco and 70% of tobacco grown in the U.S. Southeast is grown from varieties developed at NC State. Charles and Marilyn Stuber Distinguished Professor of Plant Breeding Ramsey Lewis continues that work and maintains the U.S. Nicotiana germplasm collection, a seed library dating back to the 1930s.

Growing tomatoes is a more than $32 million industry in North Carolina, an estimated 60% of which are NC State varieties bred to improve disease resistance, fruit quality and heat-stress tolerance in any environment. Under breeder Dilip Panthee, the program has

The Covington sweetpotato, released in 2005 by NC State, is a variety now grown in 90% of North Carolina sweetpotato fields, generating more than $3.5 billion in revenue for the state. NC State’s program, spearheaded by William Neal Renoylds Distinguished Professor Craig Yencho, has released dozens of edible varieties and some 30 ornamental sweetpotatoes, including the heartshaped Sweet Caroline Mahogany.

NC State researchers have worked with blueberry germplasm and breeding for 90 years. Ripe for more advancement in the field, the current program, led by Associate Professor Hudson Ashafri, will soon bring new varieties of the antioxidant-filled fruit to the market.

Strawberries, Blackberries and Raspberries

Gina Fernandez, John D. and Nell R. Leazar Distinguished Professor, tests new breeds of strawberries, raspberries and blackberries at four NC State research stations. The goal is to develop fruit that is disease-resistant, tastes great, and is adaptable to climates in various regions of the state.

Assistant Professor Jeffrey Dunne leads the NC State Peanut Breeding Program, one of the few in the country that focuses on Virginia-type peanuts. His work ensures those salted, roasted-inshell peanuts enjoyed by sports fans at the ballpark have the right shape, color and perfect flavor profile.

NC State’s Wheat and Small Grains Breeding Program is one of seven in the SunGrains breeding cooperative, the largest coordinated public breeding effort in the U.S. The group has released 77 varieties of wheat, oats, triticale and rye with the help of the USDA’s Eastern Genotyping Lab, located on NC State’s campus.

JC Raulston Distinguished Professor Tom Ranney, who has introduced more than 30 new plants and generated some $2.5 million in royalties for NC State during his 35 years with the Ornamental Breeding Program.

New turfgrass cultivars such as Lobo™ Zoysiagrass, developed by Professor Susana Milla-Lewis and her team, ensure that turfgrass stands are dense, use less water, outcompete weeds, are quick to establish and can survive across different climates.

By Dee Shore

After a century of making history in agricultural research, education and Extension, the departments of Crop and Soil Sciences and Prestage Poultry Science are primed for the future.

One hundred years ago, the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences' departments of Crop and Soil Sciences and Prestage Poultry Science came into being.

Of course, there had been research, teaching and extension work in poultry, crop and soil sciences well before 1924, but both departments formally recognize that year — the year after the School of Agriculture’s founding — as their official start.

Back then, it was a different university, a different state and a different world. The first students of these departments were almost exclusively young men — undergraduates who came off their family farms, where many of them would return.

Today, the student body is much more diverse, coming from around the state, nation and world to pursue associate's, bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees.

In 1924, concern about the boll weevil’s impact on cotton was top of mind. The following year’s Census of Agriculture would count 279,767 mules on the state’s

283,482 farms, and reported that the average farm size was 65.6 acres.

Today, concern is high over climate change and its potential impact on agriculture and our environment. Farms are far fewer — less than 43,000 statewide — but, at an average of 190 acres each, much larger.

And mules? Well, it appears the census doesn’t count them anymore.

What hasn’t changed? A look through the university’s 1924 yearbook, the Agromeck , provides a clue.

A column called “In Retrospect” reads, “The two great ideals that have been predominant throughout the entire development of State College are loyalty and service. May she keep these ideals ever before her as she evolves into that greater college of the future.”

In the Prestage Department of Poultry Science and the Department of Crop and Soil Sciences, these ideals remain embedded in their very foundation: loyalty and forward-facing service to humankind.

“The two great ideals that have been predominant throughout the entire development of State College are loyalty and service. May she keep these ideals ever before her as she evolves into that greater college of the future.”

From the university’s 1924 yearbook

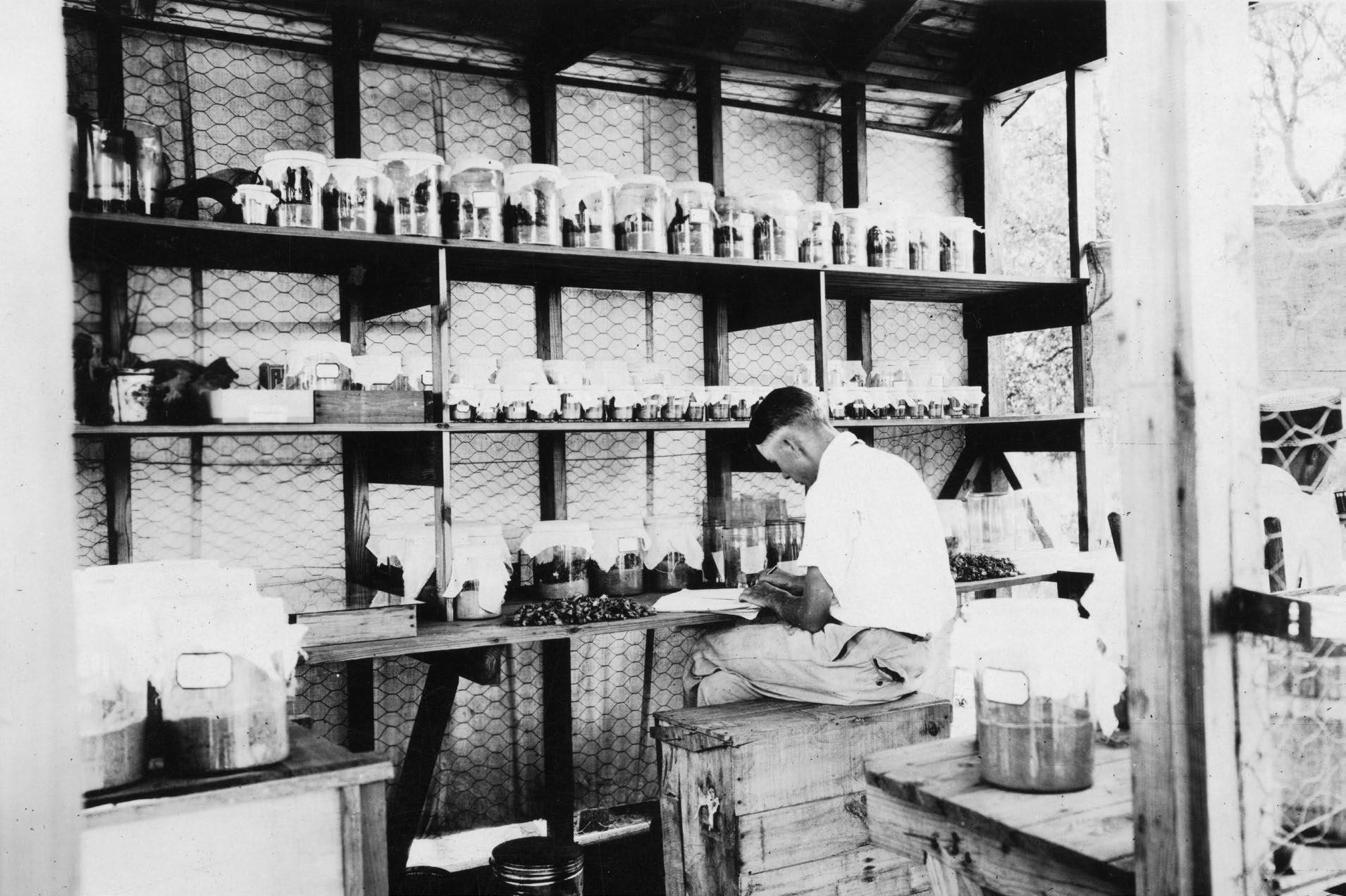

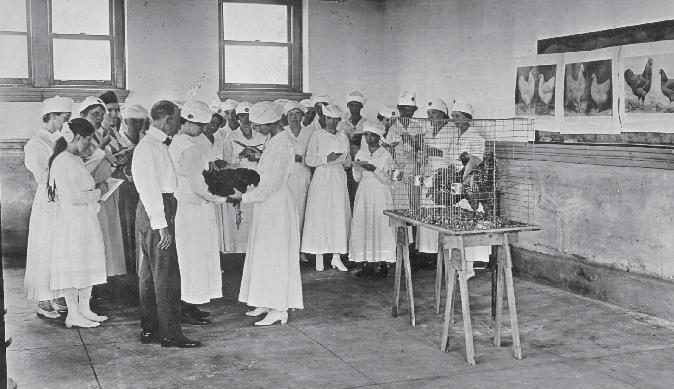

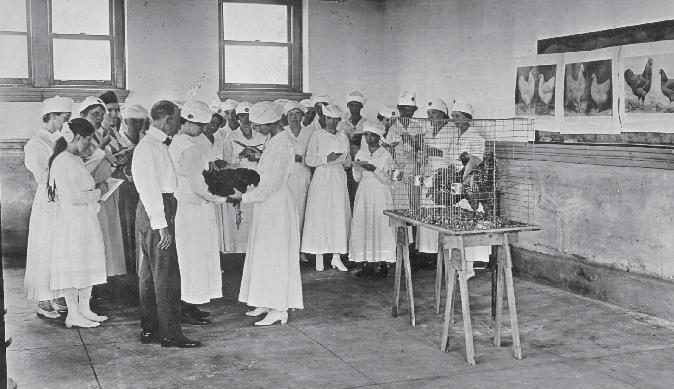

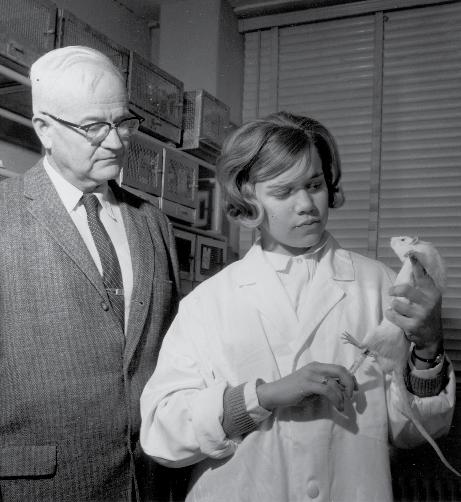

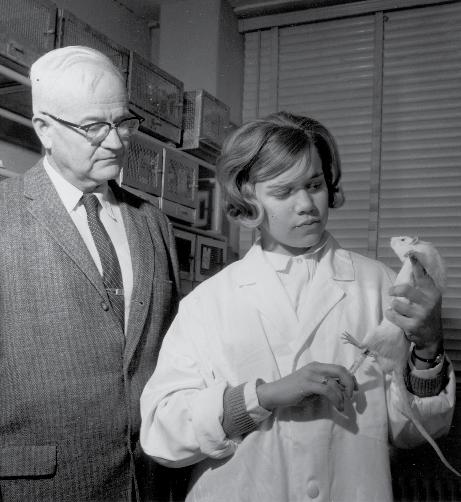

< Top to bottom: Poultry Processing, 1950s; Crop science students in classroom, circa 1920; Boll weevil field laboratory, Aberdeen, North Carolina, 1920s. Photos courtesy of University Archives Photograph Collection.

From its earliest beginnings, the Prestage Department of Poultry Science has helped the state’s poultry industry grow and thrive.

With the department's help, North Carolina went from being a place where poultry was a small part of most farms to being the nation's leading poultry exporter, ranking first in turkeys and in all cash receipts from poultry and eggs, fourth in broilers and eighth in eggs.

Prestage Poultry Science’s efforts evolved out of research, teaching and Extension work that predates the department. In 1895, the North Carolina Agricultural Experiment Station added a poultry division, the forerunner to the department’s now world-class research program. Propelled by a $10 million gift in 2012 from Bill and Martha Prestage, co-founders of Prestage Farms, the program brings knowledge of genetics, genomics, immunology, physiology, welfare and more to bear on ensuring the industry can grow in ways that are good for the state’s economy and environment.

Poultry teaching at NC State University got its start in 1900, when what was then known as the North Carolina College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts established its first poultry courses, designed mainly for those who would go on to raise poultry on their family farms.

Now, artificial intelligence and data analytics are becoming part of the curriculum. Today’s undergraduate and graduate students are deepening their knowledge and understanding of the science behind poultry production and preparing to lead the industry into the future.

Extension, too, is shaping the industry’s future. In the 1920s, Extension worked

with farm women interested in producing poultry and eggs. Now, it helps not only backyard growers keep their chickens healthy, but also some of the world's biggest companies address such issues as waste management, and flock health and disease management.

The department is also looking at ways to improve animal welfare and collaborate with the College of Veterinary Medicine and the state department of agriculture and consumer services to help stop the spread of menacing poultry diseases. Frank Siewerdt, the head of Prestage Poultry Science, says that NC State’s Food Animal Initiative, led by the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, will put NC State on the map as the world’s top institution in poultry and animal production. The initiative suggests a bright future for poultry.

“This department is and will be here to do two things,” he says. “One is to support our industry, which is the largest industry in the state — not

just in agriculture, but in general. The other is to be the leading generators of knowledge in poultry science and related disciplines.

“We will grow our reputation of being the place poultry companies can turn to for knowledge. Our strong collaborative ties with industry, such as the support from the Prestages, are proof that the department's valuable role is recognized by our stakeholders."

Researching Animal Welfare

To keep outbreaks of the highly pathogenic avian influenza from spreading, poultry farms follow strict biosecurity measures. Still, there have been losses, largely because the disease can spread from migratory birds.

That’s worrisome, because of the economic toll outbreaks could take in North Carolina, where poultry is the leading agricultural commodity. Not only that, avian influenza has been known to infect other animals, including dairy cattle, and even, in rare cases, humans.

To help minimize losses, a team of NC State Extension specialized poultry agents affiliated with the Prestage Department of Poultry Science has been at the forefront of efforts to educate commercial and small flock owners about the disease and how to compost dead birds in ways that deactivate the virus.

Though the impact of that work is hard to measure, agent Richard Goforth says, “I think it speaks volumes that, yes, we have had some commercial cases in North Carolina, but relative to the amount of poultry we have in this state, the number of outbreaks has been low, and we haven’t had continual spread.”

Staying vigilant and developing new ways to protect flocks will be key for maintaining health — not just of poultry, but of people and other animals, too.

Because healthy chickens provide consumers with nutritious eggs and meat, proper treatment of the birds is not just a matter of ethics, it also makes good business sense. In the Prestage Department of Poultry Science, Assistant Professor Allison Pullin is working to ensure that poultry farmers have the information they need to make wise animal welfare decisions.

One of Pullin’s research projects uses thermal imaging to measure laying hens’ stress response, which could help identify genetic strains best suited for cage-free environments. Those that are more fearful of sudden environmental change might be more easily stressed in a cage-free setting. When stressed, birds could injure themselves by flying up and colliding with housing structures or be more difficult to handle.

The #1 commodity in N.C. is poultry, providing around 41% of farm cash receipts. With 2M jobs and nearly $34B in generated taxes, poultry continues to be one of the leading drivers of the state's economic growth.

N.C. ranks #8 nationally in egg production.

32K N.C. families with backyard flocks produce ~500K eggs daily for local communities.

N.C. is the largest U.S. turkey producer by weight, providing $9.5B in economic impact.

N.C. produces 10% of all broilers in the U.S., resulting in 27K fulltime jobs and 73K indirect jobs.

Source: Prestage Department of Poultry Science 2023 Annual Report and Poultry Production and Value 2023 Summary, U.S. Department of Agriculture

In another project, Pullin and her collaborators use radio-frequency identification, or RFID, to measure how often chickens peck at their drinking stations. Some birds peck at drinkers for prolonged periods, which could lead to water spillage and wet bedding that can cause health problems. The researchers want to understand what drives the behavior, which could give them a better idea of how to solve the problem.

“When we think about any kind of farm management change to improve animal welfare,” Pullin says, “it’s always important to make sure that we have evidence to guide our decision making, because things that might sound good to us may not be the best thing for the bird.”

1900

at State University

Poultry staff, 1928

1921 1924

1924

Poultry Department is established as one of six departments in the School of

Poultry Department is established as one of six departments in the School of Agriculture.

1924-31

1924-31

The North Carolina of Agriculture and Arts establishes its first poultry courses.

The North Carolina College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts establishes its first poultry courses. 1900

1912

1912

Poultry classes become part of the Department of Animal Industry curriculum.

Poultry classes become part of the Department of Animal Industry curriculum.

1917

1917

Eli Ivey becomes the first student to from poultry a B.S. He went to becomes an in the department and later the poultry department head at what Auburn University.

John Eli Ivey becomes the first student to graduate from poultry with a B.S. degree. He went on to becomes an instructor in the department and later the poultry department head at what became Auburn University.

Dennis H. Hall Jr. receives the first master’s degree in poultry science with the thesis “Factors That Influence Egg Production.”

Dennis H. Jr. the first degree in poultry science with the thesis “Factors That Influence Egg Production.”

Culling class circa 1920

1935

Roy Dearstyne’s bacillary white diarrhea research aids the development of testing procedures for overcoming Salmonella pullorum . This leads to a subsequent increase in poultry flock sizes. In 1968, the Dearstyne Avian Health Center is named for him.

Roy Dearstyne’s bacillary white diarrhea research aids the development of testing procedures for overcoming Salmonella . This leads to a subsequent increase in poultry sizes. In 1968, the Dearstyne Avian Health Center named him.

Home demonstration inspecting club member’s flock of White Orpingtons, 1924

Home demonstration agent inspecting club member’s flock of White Orpingtons, 1924

1926

1926

Poultry Extension is transferred from the N.C. Department of Agriculture to the A&M College. Farmers are encouraged to increase their flock sizes.

Poultry Extension is transferred from the N.C. Department of Agriculture to the A&M College. Farmers are encouraged to increase their flock sizes.

Black and white photos courtesy of University Photograph Collection.

The department’s first genetics research cooperator is H. Bostian (later an NC State chancellor).

Reinard Harkema becomes the second cooperator in 1938, studying parasites of poultry.

The department’s first genetics research cooperator is Carey H. Bostian (later an NC State chancellor). Reinard Harkema becomes the second research cooperator in 1938, studying parasites of poultry.

Poultry laboratories, Scott Hall

Poultry laboratories, Scott Hall

1952

1952

Hall opens as the home of the Department of Poultry.

Scott Hall opens as the home of the Department of Poultry.

The Lake Wheeler Road Poultry Education Unit is dedicated. It has grown to five units: the Chicken Education Unit, the Talley Turkey Education Unit, the Animal and Poultry Waste Management Center, the Poultry Teaching Unit, and the Feed Mill Education Unit.

The North Carolina feed industry pools resources to build a new research and teaching feed mill at the Lake Wheeler Road Field Lab.

Jim Petitte receives patents for a method of developing avian embryonic stem cells. Companies using his licensed technology found the cells worked well for vaccine development, and today avian embryonic stem cells make up much of the vaccine industry.

The Poultry Department is renamed the Department of Poultry Science.

The Agricultural Institute starts a poultry option for the two-year associate's degree program.

The department is renamed Prestage Department of Poultry Science after Bill and Marsha Prestage make a transformative $10 million gift.

President Joe Biden pardons Chocolate and Chip, turkeys that now call NC State home.

The Golden LEAF Foundation pledges $500,000 that, combined with other industry contributions, will help build a state-of-the-art aviary at the Piedmont Research Station in Salisbury.

The N.C. legislature provides funding for a new faculty position in developmental biology/biotechnology, with the long-term goal of applying biotechnology to increase the efficiency of performance in economic avian species.

Jason Shih and Mike Williams isolate a bacterium from a poultry waste digester with the ability to live on feathers alone. That leads to additional studies on the isolation of the gene involved, purification of an enzyme produced by the gene and founding of BioResource International in 1999. Novus International acquired the global biotechnology company specializing in the research, development and manufacture of high-performance enzyme feed additives.

The NC State University Department of Crop and Soil Sciences has a rich 100-year history of growing agricultural and environmental sciences in North Carolina and around the globe, but the department has never rested on its laurels. Its focus has been, and will remain, on the future.

Department Head Jeff Mullahey points to several forward-looking projects that faculty, staff and students are working on, many of which involve realizing the promises of precision agriculture by deploying the latest in advanced technologies.

“It goes from the simple UAV, or drone, to what they call deep learning, where a computer is using machine learning to tell you answers to questions that you didn’t even know existed,” he says.

Researchers and Extension specialists are also digging into agricultural and soil management issues related to the challenges of climate change. Projects include developing strategies using wetland buffers to help grain farmers deal with saltwater intrusion in coastal areas, and adding soil amendments to sequester carbon in the earth.

Crop and Soil Sciences is also making significant progress in what’s called “speed breeding,” Mullahey notes. Conventional breeding has been time-consuming, taking upwards of a decade to produce an improved cultivar. But new methods are cutting that time by years.

“We’re using genomic selection with molecular markers and high-throughput phenotyping with drones in the field to reduce the traditional breeding cycle of crops by several years,” Mullahey says. “Computational biology enables researchers to analyze big datasets … leading to shortened breeding cycles.”

Mullahey is quick to point out that such advancements haven’t come from thin air.

“We used momentum gained by a multitude of faculty who have come through this department,” he says. “Their innovation and discoveries helped us get where we are today. They laid the building blocks that have allowed the rest of us to come along and to add to it.

“The hardcore basic science that they laid down on the third and fourth floors of Williams Hall — without that, the applied science that in many ways we are known for today could not go on to the next step,” Mullahey adds.

Just as the department’s giants of the past couldn’t have predicted all of today’s challenges in crop and soil sciences, those of the present cannot say with certainty what’s next.

Still, Professor Bob Patterson, who was a student in the 1950s and joined the faculty in the 1960s, hopes that a common thread from the department’s earliest days will carry forward: “I hope we can continue to provide opportunities for all those students who we attract to become prepared in ways that are important to them to live the life that they want to live,” he says, “and in such a way that their head and their heart can come together in a healthy way.

“That’s an answer from the academic side, but I think it applies to research and Extension, too. It’s what we want for all.”

A multidisciplinary team of NC State University researchers, led by crop and soil sciences faculty, is delivering the science and technology needed to curb the effects of climate change in agriculture.

Through an effort known as Climate Adaptation Through Agriculture and Soil Management, or CASM, the group has made headway in helping farmers deal with grain crop damage from saltwater intrusion and in exploring ways to use biochar to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from soil.

“These findings are expected to have profound ramifications for optimizing soil amendments to mitigate gas emissions.”

expected profound optimizing amendments to

The CASM saltwater intrusion team, led by soil scientist Matt Ricker, has worked with Cooperative Extension professionals to help growers in Hyde County, where saltwater intrusion onto crop lands is readily apparent, understand the importance of soil testing and selecting salt-tolerant plant varieties.

Soil microbiologist Wei Shi leads a CASM team researching soil amendments to increase carbon storage in agricultural land. Often, efforts to sequester carbon in the soil have been accompanied by increases in other greenhouse gas emissions, but the team has uncovered key soil biophysical and biochemical processes that block the emissions from biochar, an amendment made from organic materials that have been heated without oxygen.

As CASM coordinator and soil science professor Josh Heitman says, “These findings are expected to have profound ramifications for optimizing soil amendments to mitigate gas emissions.”

TOOLS PROVIDE GROWER ADVANTAGES

With a new online tracking tool called Beans Gone Wild, North Carolina’s soybean growers can stay up-to-the-minute on in-season crop problems and recommendations from NC State Extension.

The visual mapping tool alerts stakeholders of regional issues and elevates research-based information.

“...we have a tool that empowers farmers with accessible, data-driven recommendations that they can use on their individual farms.”

“For soybean producers, it’s useful to know what problems other farmers are facing,” says Jeff Chandler, research coordinator for the N.C. Soybean Producers Association. “In the past, we didn’t always have timely or accurate information on what’s occurring where.”

Rachel Vann played a key role in developing the simple-touse tool. One of her latest projects, a web-based soybean growers’ decision tool, is set to go live this fall. The tool will allow growers to pinpoint their location and get precise, site-specific, data-backed recommendations for planting dates, maturity groups and seeding rates.

“The tool was co-developed alongside the end-user and with the end-user in mind every step of the way,” Vann says. “We feel like we have a tool that empowers farmers with accessible, data-driven recommendations that they can use on their individual farms.”

1924 The Department of Agronomy is created. Courses include farm crops, soils, plant breeding and farm machinery.

1929 Agronomy grows to 109 undergraduate students, making it the largest department in the School of Agriculture and Forestry, comprising more than one-third of the students.

1930 The Soil Conservation Service (SCS) has a direct influence on agronomy programs, with campus soil scientists providing advice and students receiving training to prepare for SCS jobs.

1936 Breeding work begins on wheat, oats and barley, as well as corn and peanuts. Soybeans are added within a few years.

Freshly dug peanuts being stacked was a common sight in the 1930s and 1940s. These small stacks protected the pods from rotting and allowed the vines and pods to dry out.**

1940 The department receives permission to offer Ph.D.s. The first recipients are N.S. Hall, R.E. Blaser and Nyle Brady. Brady goes on to become a co-author of The Nature and Properties of Soils, one of the world’s most widely used soils textbooks.

1946 The U.S. Department of Agriculture stations Clarence Hanson in the department. He studies lespedeza and alfalfa, expands the plant breeding program and carries out graduate studies. To this day, USDA scientists are affiliated with the department.

Cotton was king of the crops in N.C. during the period of 1915–30. Patterson Hall is in the background and was the home of agronomy until 1939.**

1960 With research faculty cooperating, Extension specialists expand their demonstrations into trials on farmers' fields.

Extension demonstration in a tobacco field, 1963.*

1962 The Department of Field Crops is changed to Crop Science, and the Department of Soils is changed to Soil Science.

1952 Williams Hall is completed, bringing together soil and field crops faculty who had been dispersed in several campus buildings.*

1956 With roughly 60 faculty members, the Agronomy Department is separated into the departments of Soils and Field Crops. Both work with agronomy majors, and each offer separate majors.

1970 Water quality research starts, broadening the soil science research program to include environmental quality.

1975 The soil and crop science departments have a combined 100 faculty members, larger than any other U.S. agronomy department or combined crops and soils program.

Stan Buol, professor of soil science, performing lab tests, circa 1970*

1998 The National Training Center for LandBased Technology and Watershed Protection is established. It is the world’s premier demonstration and training facility for advanced and conventional landbased wastewater technologies and related environmental technologies.

1983 Major Goodman takes over NC State’s corn breeding program. In 1986, he is inducted into the National Academy of Sciences for his world-renowned genetic research. During his career, he develops more than 90 public lines used in Asia, Central and South America and the United States.

1984 A new program in alternative sustainable agriculture begins.

1999 The Geographic Information Systems Education Laboratory opens for students to practice precision farming skills.

2016 Professor Candace Haigler discovers two major fiber shapes in commonly grown upland cotton. Her research toward a better understanding of fundamental processes in plant biology continues today to build a foundation for producing valueadded crops through genetic engineering or marker-assisted breeding.

Candace Haigler discussing details of cotton cell structure

Soil consultants determine septic system loading rates 148

A. Sanchez

2002 Pedro A. Sanchez, former soil science faculty member, receives the World Food Prize for developing methods to restore fertility to degraded soils in Africa and South America.

2005 The department’s agroecology minor, and its Agroecology Farm, take root; the minor blends ecology, agronomy, soil science, entomology and natural resource management concepts.

2020 The department announces gifts of more than $8 million to enhance studies of greenhouse gas mitigation through agriculture.

2023 CSS’ Extension team is the second-largest group of its kind in CALS and is at the forefront of stakeholder outreach and engagement:

2016 The departments of Crop Science and Soil Science reunite to form the Department of Crop and Soil Sciences (CSS).

By Amanda Kerr

“I’ve combined my love of electronic and computer engineering with agriculture.”

eilong He loves the challenge of solving a problem. So when He had the opportunity to improve the process of tracking crop growth for plant breeders, he jumped at the chance.

Traditionally, plant breeders have had to plod through densely packed rows of crops on foot to manually measure and observe the size, quality and angle of every leaf. This tedious work can come at an even greater cost if they can’t identify problems fast enough to ensure the best yield.

To help, He, a graduate research assistant in the Robotics and Automation Lab in the Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering, has spent the past year at NC State University exploring how to use machine learning in tandem with drone images to assess crop leaves faster.

“I like that you work on the problem many times and try almost every solution until you find the best way to solve the problem,” says He, who earned his undergraduate degree in electronic information technology from Wuhan University of Technology in China.

Part of the inaugural cohort of the Norma L. Trolinder N.C. Plant Sciences Initiative Graduate Student Endowment Award, He, who is pursuing his Ph.D. in agricultural engineering, feels his work is the next chapter of research started by endowment benefactors Norma and Linda Trolinder. The mother-daughter duo co-founded South Plains Biotechnologies Inc. in the 1990s and focused their work on plant genetics. Linda Trolinder went on to hold research and development roles with companies such as Bayer Crop Science and BASF.

“The Trolinder award has enabled me to devote more time and resources to my research in plant sciences,” He says. “It has facilitated my participation in academic conferences and field trips, providing invaluable opportunities to engage with esteemed scholars in plant science, which have significantly enriched my understanding and contributed to the progress of my research endeavors.”

One of those endeavors is how to better automate the process of measuring the angles of corn leaves. Breeding specialists currently have to do it by hand, which can take many hours to complete. The angle is important for determining the light and water interception within the tightly packed rows of crops.

To save breeders time, He is developing a machinelearning algorithm to generate measurements for every leaf based on drone images of a corn field. The technology, so far, is promising with an accuracy rate of more than 90%. He and his advisor, Lirong Xiang, assistant professor of biological and agricultural engineering, have been working with plant breeders, including NC State faculty Joseph Gage and Rubén Rellán Álvarez, as well as Iowa State University researcher Patrick Schnable, on leveraging this technique for large-scale studies in breeding programs.

Another project centers on developing an algorithm to identify healthy, diseased and withered leaves on tomato plants. The long-term goal, He says, is to have the algorithm correctly label the health of the leaves and then eventually predict the health of the plant.

Xiang, who runs the Robotics and Automation Lab, says the goal of this kind of research is to develop automated solutions for agriculture by leveraging technologies such as robotics, AI and machine vision.

“We aim to develop fully automated systems for collecting phenotypic traits, such as leaf angle and disease severity, to save researchers time and costs associated with manual measurement, thereby ultimately accelerating breeding programs,” Xiang says.

And watching He make meaningful progress in this work, says Xiang, is rewarding.

“He is someone who stays focused and is self-motivated, consistently demonstrating a proactive approach to learning and problem-solving,” she says.