6 minute read

Beyond The Laboratory: Our ( Possible) Genetic Futures

OUR (POSSIBLE) GENETIC FUTURES By Chelsea Kellner

As crowds poured into Raleigh’s contemporary art museum during the April 2017 art walk, one white wall began to fill with hand-written messages scribbled on neon Post-It notes.

Above was a sign: Write down one word describing how you feel about your genetic future.

Hopeful, read one note. Forgotten, said another. Diverse. Adventurous. Misunderstood.

“The idea is to bring art into the equation of understanding, analyzing and considering the future of a world that already contains genetic engineering,” said Molly Renda, exhibits program librarian with NCSU Libraries.

Titled “Art’s Work in the Age of Biotechnology: Shaping Our Genetic Future(s),” the exhibit was a partnership between NC State’s Genetic Engineering and Society Center (GES), the NCSU Libraries and CAM Raleigh. It’s part of a broader effort to maintain public education and engagement that can help guide the cutting edge innovation.

At CALS, ethics, engagement and public policy have become as much part of the gene editing conversation as Cas9 proteins and gene drives.

“The first question we ask is what you can do with a genetic engineering tool; then the second question we ask is, should you do it?” said Fred Gould, codirector of GES, William Neal Reynolds Distinguished Professor of Entomology and a member of the National Academy of Sciences.

What is gene editing?

Broadly speaking, gene editing is any biotechnical technique that modifies specific DNA sequences in the genome of a living organism. The newest methods have major implications for agriculture, food, biotechnology and bioenergy — and key research is happening in CALS.

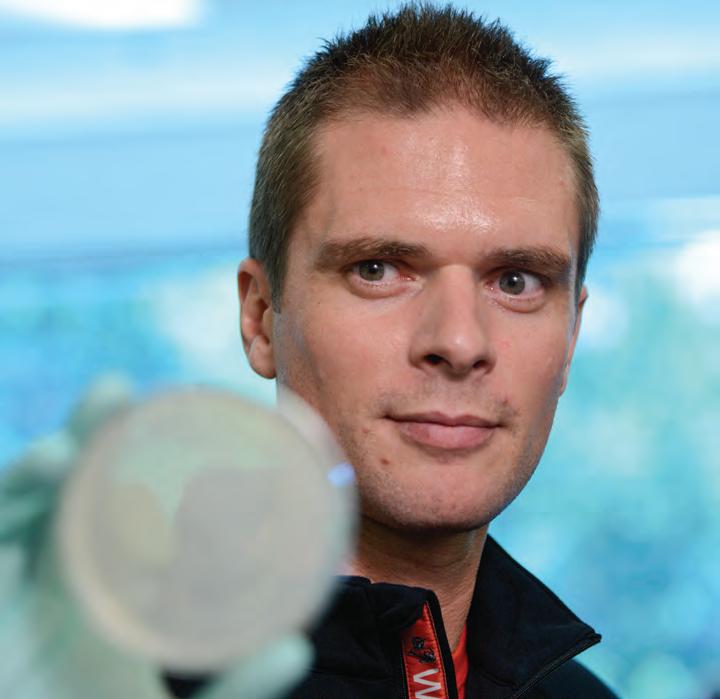

CRISPR, for example, is a tool that co-opts a microbial adaptive immune system into a cut-and-replace gene-editing system. Award-winning CRISPR pioneer Rodolphe Barrangou is associate professor of food science, the Todd R. Klaenhammer Distinguished Scholar in Probiotics Research and the CRISPR Lab lead. His long-term goal: solve the problem of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

“We are first trying to address challenges that are nobrainers, not controversial to anyone: Can we prevent the rise of antibiotic resistance? Can we help cure diseases that currently have no cure?” Barrangou said.

It’s a mistake to think of gene editing as a single entity, cautions Jennifer Kuzma, co-director of GES and the Goodnight-NC GlaxoSmithKline Foundation Distinguished Professor in Social Sciences. There are a variety of methods, some intended to stay in the lab, others whose impact requires release into the general population.

“When we start talking about ethics, those questions are dependent on how those tools are being used, and why, and where,” Kuzma said.

Once guidelines are set up, scientists should and will abide by them, Barrangou said, but he believes they largely need to be hammered out by a variety of informed experts.

Enter the ethicist

For this, Barrangou points to experts like regulatory agencies, think tanks, NGOs — and ethicists, like Kuzma. She believes that the most crucial component of ethical genetic futures is public awareness and education.

Kuzma said.

The hot debate around GMOs taught hard lessons on when and how scientists roll out new technologies for public consumption. Some of those lessons have led to another key element of what’s next, Gould explains: Scientists have also focused on developing the ability to assess whether genetic editing causes unintended changes to the genome in real time.

“As we’re developing the technology, we’re simultaneously developing checks on it,” Gould said.

CALS scientists are also seeking out a deeper level of public communication. For example, Kuzma, Gould and CALS student Nicole Gutzmann, are currently researching the meaning of responsible innovation in genetic engineering. Now in the second year of a grant from the National Science Foundation with Kuzma as principal investigator, they are exploring what it means to innovate responsibly in this area. “It’s training students to think more deeply about responsibility and innovation, and it’s also getting communities of practitioners to think more responsibly about what they’re doing,” Kuzma said. “We are directly addressing these questions in a variety of ways at

NC State.”

It’s impossible to discuss the future of gene editing without talking about who might control the intellectual property rights to the technology — and that’s up for grabs, Barrangou said, in what he predicts will be “the biggest IP patent battle of all time.”

CRISPR and other gene editing technologies have potential billion-dollar value to industries ranging from pharmaceuticals to biofuel. The development of the technology is difficult to pinpoint at a particular laboratory, as scientists around the world have built on one another’s breakthroughs, some developed simultaneously.

“There are many people who would like to get their hands on a piece of the intellectual property, who are willing to do everything in their power to put a claim on the whole thing,”

Barrangou said. “We have never seen this happen before.”

Patents on aspects of CRISPR technology are currently held by, for example, the Broad Institute and the University of California at Berkeley. A current fight is to nab the patent on having invented the foundation itself: the use of CRISPR to change DNA.

Whoever owns that, owns the price of gene editing in the future.

“The incentives are so big — imagine somebody having a patent on pizza dough,” Barrangou said.

And the longterm impact of the outcome depends on who wins — and what they decide to do with it.

NC State is not involved in the race, but it’s an outside factor with implications being examined at the university level by interdisciplinary groups like GES.

“If you don’t make the technology accessible to certain groups like developing countries and nonprofits, that doesn’t do much for democracy or social good,” Kuzma said.

Constructing the science highway

That’s where regulation could come in — but it’s tricky. Public safety is paramount, but too-tight controls could drive innovation offshore, bleeding scientists to countries with fewer restrictions.

Issues of inequality also loom large, both in access to the technology itself and in the capital investments in facilities and equipment necessary in order to put it to use.

“If you put too many financial or difficulty constraints on technology, are we missing out on something we have a moral imperative to do, like cure a disease or save an endangered species?” Kuzma said.

Barrangou compares the development of cutting-edge science to road construction: You have your previously constructed highways, already lined with guide rails and governed by a speed limit. But when you need new stretches of road across unexplored terrain, it requires specialists with both the desire and the skills to clear a path.

NC State’s emphasis on interdisciplinary collaboration has already begun laying groundwork to both advance and guide that process.

“We have choices to make about our genetic future, and there are many different directions we can go,” Gould said. “How do we make these choices?

Which voices are heard? That’s a piece where NC State can be very important in actively guiding the technology.”